The Place of the Honour in Twelfth-Century Society

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

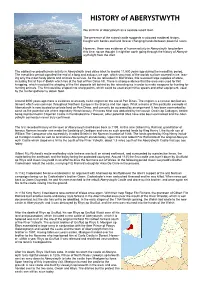

HISTORY of ABERYSTWYTH

HISTORY of ABERYSTWYTH We all think of Aberystwyth as a seaside resort town. The presence of the ruined castle suggests a coloured medieval history, fraught with battles and land forever changing hands between powerful rulers. However, there was evidence of human activity in Aberystwyth long before this time, so we thought it might be worth going through the history of Aberyst- wyth right from the start. The earliest recorded human activity in Aberystwyth area dates back to around 11,500 years ago during the mesolithic period. The mesolithic period signalled the end of a long and arduous ice age, which saw most of the worlds surface covered in ice, leav- ing only the most hardy plants and animals to survive. As the ice retreaded in Mid Wales, this revealed large supplies of stone, including flint at Tan-Y-Bwlch which lies at the foot of Pen Dinas hill. There is strong evidence that the area was used for flint knapping, which involved the shaping of the flint deposits left behind by the retreating ice in order to make weapons for hunting for hunting animals. The flint could be shaped into sharp points, which could be used as primitive spears and other equipment, used by the hunter gatherer to obtain food. Around 3000 years ago there is evidence of an early Celtic ringfort on the site of Pen Dinas. The ringfort is a circular fortified set- tlement which was common throughout Northern Europe in the Bronze and Iron ages. What remains of this particular example at Aberystwyth is now located on private land on Pen Dinas, and can only be accessed by arrangement. -

Tonbridge Castle and Its Lords

Archaeologia Cantiana Vol. 16 1886 TONBRIDGE OASTLE AND ITS LORDS. BY J. F. WADMORE, A.R.I.B.A. ALTHOUGH we may gain much, useful information from Lambard, Hasted, Furley, and others, who have written on this subject, yet I venture to think that there are historical points and features in connection with this building, and the remarkable mound within it, which will be found fresh and interesting. I propose therefore to give an account of the mound and castle, as far as may be from pre-historic times, in connection with the Lords of the Castle and its successive owners. THE MOUND. Some years since, Dr. Fleming, who then resided at the castle, discovered on the mound a coin of Con- stantine, minted at Treves. Few will be disposed to dispute the inference, that the mound existed pre- viously to the coins resting upon it. We must not, however, hastily assume that the mound is of Roman origin, either as regards date or construction. The numerous earthworks and camps which are even now to be found scattered over the British islands are mainly of pre-historic date, although some mounds may be considered Saxon, and others Danish. Many are even now familiarly spoken of as Caesar's or Vespa- sian's camps, like those at East Hampstead (Berks), Folkestone, Amesbury, and Bensbury at Wimbledon. Yet these are in no case to be confounded with Roman TONBEIDGHE CASTLE AND ITS LORDS. 13 camps, which in the times of the Consulate were always square, although under the Emperors both square and oblong shapes were used.* These British camps or burys are of all shapes and sizes, taking their form and configuration from the hill-tops on which they were generally placed. -

Information on This Tour

1066 And All That Travel The tour starts and finishes at the Rose and Crown Hotel, Tonbridge 125 High Street, Tonbridge TN9 1DD United Kingdom Tel: +44 (0)3330 034292 Please note that transport to the hotel is not included in the price of the tour. Transport Driving directions to the hotel: Take exit 2A from M26, A20 to A25/A227, and follow the A227 to Tonbridge High Street. At the roundabout, take the 1st exit onto London Road/A20 and then turn right onto Maidstone Road/A25. Continue to follow A25 for 2.5 miles and at the roundabout, take the 2nd exit onto Borough Green Road/A227, continue onto the High Street and the hotel will be on the left. If you are travelling by train: Tonbridge railway station is the closest to the hotel, ½ mile away. Accommodation Rose and Crown Hotel, Tonbridge The Best Western Rose & Crown Hotel in the heart of Tonbridge is full of old-world charm. Opposite Tonbridge Castle, it offers traditional hospitality, with the warmest of welcomes guaranteed. Retaining the unique feel of the original building, you’ll be treated to oak beams and Jacobean panels, while all renovations and extensions have been sympathetic to the its original design. Facilities include a bar and restaurant. Each of the bedrooms feature TV, radio, telephone and tea and coffee making facilities. There is free parking on-site. Additional details can be found via the hotel website: https://www.bestwestern.co.uk/hotels/best-western-rose-and-crown-hotel-83792 Check-in and departure from the hotel On the day of arrival you will be able to check-in at the hotel from 14.00, and the tour manager will meet you in the evening at the welcome reception. -

Corrections to Domesday Descendants As Discussed by the Society/Genealogy/Medieval Newsgroup

DOMESDAY DESCENDANTS SOME CORRIGENDA By K. S. B. KEATS-ROHAN Bigod, Willelm and Bigod comes, Hugo were full brothers. Delete ‘half-brother’. de Brisete, Jordan Son of Ralph fitz Brien, a Domesday tenant of the bishop of London. He founded priories of St John and St Mary at Clerkenwell during the reign of Stephen. He married Muriel de Munteni, by whom he had four daughters, Lecia wife of Henry Foliot, Emma wife of Rainald of Ginges, Matilda, a nun of Clerkenwell, and Roesia. After his death c. 1150 his widow married secondly Maurice son of Robert of Totham (q.v.). Pamela Taylor, ‘Clerkenwell and the Religious Foundations of Jordan de Bricett: A Re-examination’, Historical Research 63 (1990). de Gorham, Gaufrid Geoffrey de Gorham held, with Agnes de Montpincon or her son Ralph, one fee of St Albans abbey in 1166. Kinsman of abbots Geoffrey and Robert de Gorron. Abbot Geoffrey de Goron of St Albans built a hall at Westwick for his brother-in-law Hugh fitz Humbold, whose successors Ivo and Geoffrey used the name de Gorham (GASA i, p. 95). Geoffrey brother of Abbot Robert and Henry son of Geoffrey de Goram attested a charter of Archdeacon John of Durham c. 1163/6 (Kemp, Archidiaconal Acta, 31). Geoffrey’s successor Henry de Gorhan of Westwick (now Gorhambury) held in 1210 (RBE 558). VCH ii, 393. de Mandeville, Willelm Son of Geoffrey I de Mandeville of Pleshy, Essex, whom he succeeded c. 1100. He also succeeded his father as constable of the Tower of London, and office that led to his undoing when Ranulf, bishop of Durham, escaped from his custody in 1101. -

A Vernacular Anglo-Norman Chronicle from Thirteenth- Century Ireland*

"GO WEST, YOUNG MAN!": A VERNACULAR ANGLO-NORMAN CHRONICLE FROM THIRTEENTH- CENTURY IRELAND* William Sayers The vernacular literary record of the Anglo-Norman invasion and settlement of twelfth- and thirteenth-century Ireland is a sparse one. Leaving to one side the native annals and the more indirect reflection of these events as a stimulus to the compilation of the great codices such as the Book of Leinster and the Book of the Dun Cow,^" only two documents are extant in the French language. One, little marked by Anglo-Norman dialect features, is a poem from 1265 commemorating the 2 completion of trench and bank fortifications at New Ross. The other, more substantial work is a chronicle of 3459 rhymed octosyllabic couplets in Anglo-Norman French, dated to 1225 or 1230; the single manuscript is incomplete at beginning and end. With the exception of the introductory episode, the body of the work commences with events in 1166, details the advent of the Cambro- Norman adventurers and the first imposition of English power in Ireland, and may well have ended with the death of a major figure in 1176. Although more restricted in temporal span and somewhat more in scope than Giraldus Cambrensis' Expugnatio hibernica, dating from 1188-89, it has served historians as a major source for this last surge of Norman expansionism. The manuscript was last edited in 1892 by Goddard H. Orpen as The Song of Dermot and the Earl and served as key evidence for much of his Ireland Under the Normans.^ In fact, M. Domenica Legge, in her authoritative 119 120 Anglo-Norman Literature and its Background, claims that "the editor had, 4 very naturally, an exaggerated idea of its historical value. -

344 History and Antiquities of Leicestershire

344 HISTORY AND ANTIQUITIES OF LEICESTERSHIRE. II. GILBERT, earl of ANGIE, or EWE, in Normandy.^ .... III- WILUAM THE=pMaud, dau. of Baldwin- , — ' CONQUEROR33. J 5thearl of Flanders, fur-' Richard , son of Gilbert, came into England with the Conqueror, 1066. named The Gentle , s— _J ,- 1 Gilbert Fitz Richard "', son and heir, first=pAdeliza, dau. of Henry, the first of the name, king of England earl of Clare, died 1152. Cleremont. youngest son, died Dec. 1, 1135. Richard Fitz Gilbert 3, 2d earl of Clare,=pAdeliza, sister of Robert Consul, earl of=p dau. of Robert Fitz and lord of Tunbridge, in Kent; I Randulph carl Gloucester 3', base son. Hammond, lord of Car- died 1156. j of Chester. boile in Normandy. 1. Gilbert24, earl of 2- Roger de Clare26, brother and=pMaud, dau. and William Consu!,=pHawifia, dau. of Clare and Here- heir of Gilbert, was earl of Clare I heir of James earl of Glou- Rob. Bossu, earl ford, died s. p. and Hereford ; died 1174. St. Hillary. cester. of Leicester. 1 — ' Richard '*, earl of Clare and Here-=pAmicia, 2d dau. and Mabell, eldest dau. and Isabel, 3d=pjohn, 4th son of king ford/" 1, die1*1 d 1218f^ , and1 was 1*burie1 d coheir1* , was1 burie' 1d " in coheir1" , marr. AAlmeril * c 1dau . an1d I f Hen.llT T 1 . earT l of* fv~ > Glou• ^~^ - in the priory or Tunbridge. Tunbridge priory. de Montfort, earl of coheir. | cester in right of his Evreux in Normandy. I wife. 1 1 Gilbert de Clare27, earl=^=lfabel, 3d dau. of William Marshal the Walter de Burgh, earl of Ulster m right of of Gloucester and elder, sister and coheir of Anselm earl his wife, heir of Hugh Fortibus, earl of Hereford. -

Regesta Regum Anglo-Normannorum, 1066-1154

:CD ;00 100 •OJ !oo CjD oo /!^ REGESTA WILLELMI CONQUESTORIS ET WILLELMI RUFI 1066-1100 OXFORD UNIVERSITY PRESS LONDON EDINBURGH GLASGOW NEW YORK TORONTO MELBOURNE BOMBAY HUMPHREY MILFORD M.A. PUBHSHER TO THE UNIVERSITY REGESTA REGUM ANGLO -NORMANNORUM 1066-1154 VOLUME I REGESTA WILLELMI CONQUESTORIS ET WILLELMI RUFI 1066-1100 EDITED VVITH INTRODUCTIONS NOTES AND INDEXES BY H. W. C. DAVIS, M.A. FELLOW AND TUTOR OF BALLIOL COLLEGE, OXFORD SOiAIETIME FELLOW OF ALL SOULS COLLEGE WITH THE ASSISTANCE OF R J. WHITWELL, B.Litt. OXFORD AT THE CLARENDON PRESS M UCCCC XIII 190 J)37 Y.l PREFACE This is the first of three volumes covering the period of the Anglo-Norman kings (1066-1154). The second and third volumes are far advanced, and will shortly be in the press. The object of ^ the series is to give a calendar, chronologically arranged and the of critically annotated, of the royal acts of period, and some cognate documents which are valuable for the historian. The first care of the editor has been to call attention to materials which iUustrate the development of law and institutions. But the interests of the genealogist and the topographer have not been neglected. Pains have been taken to record the names of persons, and the more important names of places, which are mentioned in the docu- ments. The collection includes charters issued in and for Normandy. Norman archives have not been searched for the purpose, since the Norman material is being coUected by Professor Haskins. But it seemed advisable to calendar such Norman charters as have been or are to be found in for of printed EngUsh manuscripts ; many these charters throw useful sideUghts upon EngUsh history. -

Ln M M I T E

f h " " Ln m m I t e. Cams um ov m o x g h ) C O N Q U E EN C O MP A N I S O N S . 9 Q q 3 6 8 W m ] c 3 0 x 9 “ J Rs? LAN O . HE , pl s mn lg' H A o ne r ER LD . W e find but few historians of all ag es wh o hav e been dilig ent in their ea c for t u It is t ei c ommon m et s r h r th. h r hod to tak e on tru st e dls tu b ute to th e P u blic b w ic mea a fal e oo o c e ec eiv e f om m od , y h h ns s h d n r d r a ” — t a itio al to o te it . DR YDEN C h a racter P ol bius. r d n p s r y , Qf y IN T W O VO L ME U S . VOL . II . g V <1; TINSLEY BROTHERS 8 CATHERINE S S ND , , TREET, TRA . C ONTENTS . CH AP TE R I. PAGE ’ ou de e of o o — u d Av ranch es E of Ra l Ga l , Earl N rf lk H gh , arl — e te eof e de Mowbra o of ou ce —Ro e Ch s r G fr y _ y, Bish p C tan s g r de Mowbray (his brother) CH A PT E R II. -

Family Lines from Companions of the Conqueror

Companions of the Conqueror and the Conqueror 1 Those Companions of William the Conqueror From Whom Ralph Edward Griswold and Madge Elaine Turner Are Descended and Their Descents from The Conqueror Himself 18 May 2002 Note: This is a working document. The lines were copied quickly out of the Griswold-Turner data base and have not yet been retraced. They have cer- tainly not been proved by the accepted sources. This is a massive project that is done in pieces, and when one piece is done it is necessary to put it aside for a while before gaining the energy and enthusiasm to continue. It will be a working document for some time to come. This document also does not contain all the descents through the Turner or Newton Lines 2 Many men (women are not mentioned) accompanied William the Conqueror on his invasion of England. Many men and women have claimed to be descended from one or more of the= Only a few of these persons are documented; they were the leaders and colleagues of William of Normandy who were of sufficient note to have been recorded. Various sources for the names of “companions” (those who were immediate associates and were rewarded with land and responsibility in England) exist. Not all of them have been consulted for this document. New material is in preparation by reputable scholars that will aid researchers in this task. For the present we have used a list from J. R. Planché. The Conqueror and His Companions. Somerset Herald. London: Tinsley Brothers, 1874.. The persons listed here are not the complete list but constitute a subset from which either Ralph Edward Griswold or Madge Elaine Turner (or both) are descended). -

Regesta Regum Anglo-Normannorum, 1066-1154

:CD ;00 100 •OJ !oo CjD oo /!^ REGESTA WILLELMI CONQUESTORIS ET WILLELMI RUFI 1066-1100 OXFORD UNIVERSITY PRESS LONDON EDINBURGH GLASGOW NEW YORK TORONTO MELBOURNE BOMBAY HUMPHREY MILFORD M.A. PUBHSHER TO THE UNIVERSITY REGESTA REGUM ANGLO -NORMANNORUM 1066-1154 VOLUME I REGESTA WILLELMI CONQUESTORIS ET WILLELMI RUFI 1066-1100 EDITED VVITH INTRODUCTIONS NOTES AND INDEXES BY H. W. C. DAVIS, M.A. FELLOW AND TUTOR OF BALLIOL COLLEGE, OXFORD SOiAIETIME FELLOW OF ALL SOULS COLLEGE WITH THE ASSISTANCE OF R J. WHITWELL, B.Litt. OXFORD AT THE CLARENDON PRESS M UCCCC XIII 190 J)37 Y.l PREFACE This is the first of three volumes covering the period of the Anglo-Norman kings (1066-1154). The second and third volumes are far advanced, and will shortly be in the press. The object of ^ the series is to give a calendar, chronologically arranged and the of critically annotated, of the royal acts of period, and some cognate documents which are valuable for the historian. The first care of the editor has been to call attention to materials which iUustrate the development of law and institutions. But the interests of the genealogist and the topographer have not been neglected. Pains have been taken to record the names of persons, and the more important names of places, which are mentioned in the docu- ments. The collection includes charters issued in and for Normandy. Norman archives have not been searched for the purpose, since the Norman material is being coUected by Professor Haskins. But it seemed advisable to calendar such Norman charters as have been or are to be found in for of printed EngUsh manuscripts ; many these charters throw useful sideUghts upon EngUsh history. -

Chapter Five the Earls and Royal Government

Chapter Five The Earls and Royal Government: General There are two angles from which the subject of the earls and royal government should be approached. The earls were in- volved at every level of government, from the highest offices of household and administration to the hanging of a thief on their own lands. They were also subject to the actions of government in its many forms. While it is useful to consider the activity of the earls in government separate from the impact of government upon them, there is no clear division between these two aspects. An earl that lost a legal dispute in the king's court was, as a major vassal of the king, a potential member of that same court. An earl that paid the danegeld due from his fief and vassals was both tax-collector and tax-payer. The obvious place to start an examination of the earls' role in government is the royal household, the central govern- ment institution of western kings since before Charlemagne. In Henry II's reign, several of the chief offices of the house- hold were held by earls. Two earls were recognised by Henry II as stewards in the years on either side of his succession to the throne. At some time between June 1153 and December 1154, Henry II recognised Robert earl of Leicester (d. 1168) as steward of England and Normandy (1). The earl had not been a steward under .(1) Re esta, iii, no.439. Shortly before this, the same grant had been made by Henry to Earl Robert's son, probably to avoid a too early contradiction in Earl Robert's allegiance to King Stephen: Ibid., no.438. -

Patrick Wormald Papers Preparatory to the Making of English

Patrick Wormald Papers Preparatory to The Making of English Law: King Alfred to the Twelfth Century Volume II From God’s Law to Common Law Edited by Stephen Baxter and John Hudson UNIVERSITY OF LONDON EARLY ENGLISH LAWS 2014 Published by UNIVERSITY OF LONDON EARLY ENGLISH LAWS http://www.earlyenglishlaws.ac.uk © Patrick Wormald 2014 ISBN 978-1-909646-03-2 Contents Preface v Abbreviations vi Editorial Introduction xi PART III: THE ORIGINS OF AN ENGLISH ROYAL LAW 1 Chapter 7B. Re-introductory: The Limits of Legislative Evidence 1 Chapter 8. Church and King 16 What is due to God 18 (i) Church taxation 18 (ii) Fast and Festival 54 (iii) Continence 64 What is due from God 72 (i) Ordeal 72 (ii) Reprieve and Pardon 90 Chapter 9. The Pursuit of Crime 98 The Meaning of Treason 100 (i) Forfeiture 100 (ii) The Oath 112 (iii) Burials 129 The Quality of Mercy 141 The Dynamics of Prosecution 161 Chapter 10. The Machinery of Justice 192 Introductory 192 Shire and Hundred 192 (i) Courts before the Tenth Century 192 (ii) The Tenth Century Revolution in Local Government 193 Centre and Locality 198 ‘Public’ and ‘Private’ 201 (i) The ‘Pleas of the Crown’ 202 (ii) The Judicial Duties and Perquisites of Lordship 204 (iii) ‘Sake and Soke’: the Private Hundred 208 Chapter 11. The Foundations of Title 212 ‘Bookland and Folkland’ 212 (i) Folkland 212 (ii) Bookland 214 The role of the king 217 Heirs and Legatees 220 (i) Wills 220 (ii) Litigation 226 (iii) Inheritance 226 Tenant and Lord 228 Chapter 12.