Battle Abbey Rolls’

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Normandy ~ Honfleur

SMALL GROUP Ma xi mum of 28 Travele rs LAND NO SINGLE JO URNEY SUPPLEMENT for Solo Travelers No rmandy ~ Honfleur HONORING D/DAY INCLUDED FEATURES Two Full Days of Exploration ACCOMMODATIONS ITINERARY Inspiring Moments (With baggage handling.) Day 1 Depart gateway city A >Contemplate the extraordinary bravery – Seven nights in Honfleur, France, at A Day 2 Arrive in Paris | Transfer of the Allied landing forces as you walk the first-class Mercure Honfleur Hotel. to Honfleur along the beaches of Normandy. EXTENSIVE MEAL PROGRAM Day 3 Honfleur >Immerse yourself in wartime history – Seven breakfasts, two lunches and Day 4 Mont St.-Michel with riveting details from expert guides. three dinners, including Welcome Day 5 Caen | Utah Beach | Sainte- and Farewell Dinners; tea or coffee Mère- Église >Explore the impact of World War II at with all meals, plus wine with dinner. Day 6 Honfleur the Caen Memorial Museum. – Sample authentic regional specialties Day 7 Arromanches | Omaha Beach | > during meals at local restaurants. Normandy American Cemetery | Marvel at stunning Mont St.-Michel, Pointe du Hoc a UNESCO World Heritage site , YOUR ONE-OF-A-KIND JOURNEY Day 8 Bayeux rising majestically over the tidal waters. – Discovery excursions highlight the local culture, heritage and history. Day 9 Transfer to Paris airport and >Delight in the wonderful local color depart for gateway city A – Expert-led Enrichment programs and delicious cuisine along Honfleur’s A enhance your insight into the region. Flights and transfers included for AHI FlexAir participants. picturesque harbor. – Free time to pursue your own interests. Note: Itinerary may change due to local conditions. -

Press Kit 2020 the Memorial Museum of the Battle of Normandy

Press kit 2020 The Memorial Museum of the Battle of Normandy The Battle of Normandy History explained through objects Liberty Alley , a site for remembrance in Bayeux Visits to the museum News and calendar of events Key figures www.bayeuxmuseum.com Press contact : Fanny Garbe, Media Relations Officer Tel. +33 (0)2.31.51.20.49 - [email protected] 2 The Memorial Museum of the Battle of Normandy Situated near the British Military Cemetery of Bayeux, the Memorial Museum of the Battle of Normandy narrates the battles which took place in Normandy after the D-Day landings, between 7 th June and 29 th August 1944. The museum offers an exhibition surface of 2000m², entirely refurbished in 2006. The collections of military equipment, the diorama and the archival films allow the visitor to grasp the enormous effort made during this decisive battle in order to restore peace in Europe. A presentation of the overall situation in Europe before D- Day precedes the rooms devoted to the operations of the month of June 1944: the visit of General De Gaulle in Bayeux on 14 th June, the role of the Resistance, the Mulberry Harbours and the capture of Cherbourg. Visitors can then step into an exhibition hall based on the work of war reporters – a theme favoured by the City of Bayeux which organises each year the Prix Bayeux-Calvados for War Correspondents. Visitors will also find information on the lives of civilians living amongst the fighting in the summer of 1944 and details of the towns destroyed by the bombings. -

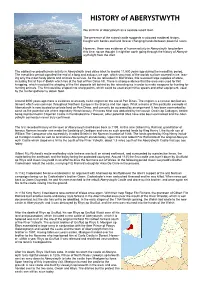

HISTORY of ABERYSTWYTH

HISTORY of ABERYSTWYTH We all think of Aberystwyth as a seaside resort town. The presence of the ruined castle suggests a coloured medieval history, fraught with battles and land forever changing hands between powerful rulers. However, there was evidence of human activity in Aberystwyth long before this time, so we thought it might be worth going through the history of Aberyst- wyth right from the start. The earliest recorded human activity in Aberystwyth area dates back to around 11,500 years ago during the mesolithic period. The mesolithic period signalled the end of a long and arduous ice age, which saw most of the worlds surface covered in ice, leav- ing only the most hardy plants and animals to survive. As the ice retreaded in Mid Wales, this revealed large supplies of stone, including flint at Tan-Y-Bwlch which lies at the foot of Pen Dinas hill. There is strong evidence that the area was used for flint knapping, which involved the shaping of the flint deposits left behind by the retreating ice in order to make weapons for hunting for hunting animals. The flint could be shaped into sharp points, which could be used as primitive spears and other equipment, used by the hunter gatherer to obtain food. Around 3000 years ago there is evidence of an early Celtic ringfort on the site of Pen Dinas. The ringfort is a circular fortified set- tlement which was common throughout Northern Europe in the Bronze and Iron ages. What remains of this particular example at Aberystwyth is now located on private land on Pen Dinas, and can only be accessed by arrangement. -

Tonbridge Castle and Its Lords

Archaeologia Cantiana Vol. 16 1886 TONBRIDGE OASTLE AND ITS LORDS. BY J. F. WADMORE, A.R.I.B.A. ALTHOUGH we may gain much, useful information from Lambard, Hasted, Furley, and others, who have written on this subject, yet I venture to think that there are historical points and features in connection with this building, and the remarkable mound within it, which will be found fresh and interesting. I propose therefore to give an account of the mound and castle, as far as may be from pre-historic times, in connection with the Lords of the Castle and its successive owners. THE MOUND. Some years since, Dr. Fleming, who then resided at the castle, discovered on the mound a coin of Con- stantine, minted at Treves. Few will be disposed to dispute the inference, that the mound existed pre- viously to the coins resting upon it. We must not, however, hastily assume that the mound is of Roman origin, either as regards date or construction. The numerous earthworks and camps which are even now to be found scattered over the British islands are mainly of pre-historic date, although some mounds may be considered Saxon, and others Danish. Many are even now familiarly spoken of as Caesar's or Vespa- sian's camps, like those at East Hampstead (Berks), Folkestone, Amesbury, and Bensbury at Wimbledon. Yet these are in no case to be confounded with Roman TONBEIDGHE CASTLE AND ITS LORDS. 13 camps, which in the times of the Consulate were always square, although under the Emperors both square and oblong shapes were used.* These British camps or burys are of all shapes and sizes, taking their form and configuration from the hill-tops on which they were generally placed. -

Calvados 2006-2007 . Rased Des Circonscriptions Suivantes : Bayeux, Isigny Honfleur Φ : Eepu Groupe Scolaire J

CALVADOS 2006-2007 . RASED DES CIRCONSCRIPTIONS SUIVANTES : BAYEUX, ISIGNY HONFLEUR Φ : EEPU GROUPE SCOLAIRE J. PREVERT BAYEUX NORD VIRE, CAEN OUEST, CAEN SUD, FALAISE, CAEN EST, LISIEUX, TROUVILLE. Φ : EEPU HOMME DE BOIS E : EEPU GROUPE SCOLAIRE J. PREVERT Φ : EEPU ARGOUGES DEAUVILLE G : EEPU HOMME DE BOIS E : EEPU ARGOUGES COURSEULLES CREUILLY E : EEPU R. DEVOS EEPU P. E Victor PORT en BESSIN Φ : EEPU CR E : EEPU UNITE A G. Le Conquérant TROUVILLE G : EEPU CR E : EEPU A. Malraux TOUQUES E : EEPU CR Φ : EEPU CENTRE HONFLEUR EEPU COURSEULLES DOUVRES E : EEPU CENTRE Φ : EEPU MARIE CURIE PONT L’EVEQUE G : EEPU MARIE CURIE TROUVILLE E : EEPU G : EEPU JACQUES PREVERT SUR MER E : EEPU MARIE CURIE TOUQUES ISIGNY SUR MER DEAUVILLE BAYEUX COURSEULLES/MER MOLAY LITTRY CREUILLY CABOURG PONT GAMBIER G : EEPU M L DIVES SUR MER L’EVEQUE Φ : EEPU PAUL DOUMER - LISIEUX E : EEPU M L DOUVRES LA E : EEPU VICTOR HUGO - CAMBREMER LE MOLAY LITTRY DELIVRANDE ARGENCES E : EEPU MARIE CURIE - LISIEUX Φ : EEPU GRPE DR DERRIEN - ARGENCES E : EEPU PAUL DOUMER - LISIEUX BRETTEVILLE L’ORGUEILLEUSE E : EEPU GRPE DR DERRIEN - ARGENCES E : EEPU MME RENE COTY - MOYAUX G : EEPU BR L’O BRETTEVILLE EEPU DOZULE DIVES EEPU TROARN E : EEPU BR L’O L’ORGUEILLEUSE Φ : EEPU COLLEVILLE – DIVES / MER E : EEPU J. GUILLOU - CABOURG BAYEUX SUD DOZULE EEPU COLLEVILLE – DIVES / MER Φ : EPPU LETOT LA POTERIE ST MARTIN DE FONTENAY G : EPPU LETOT LA POTERIE Φ : EEPU CHARLES HUARD E : EEPU LOUISE LAURENT G : EEPU CHARLES HUARD MOYAUX EPPU BELLEVUE E : EEPU CHARLES HUARD TROARN VILLERS BOCAGE -

Information on This Tour

1066 And All That Travel The tour starts and finishes at the Rose and Crown Hotel, Tonbridge 125 High Street, Tonbridge TN9 1DD United Kingdom Tel: +44 (0)3330 034292 Please note that transport to the hotel is not included in the price of the tour. Transport Driving directions to the hotel: Take exit 2A from M26, A20 to A25/A227, and follow the A227 to Tonbridge High Street. At the roundabout, take the 1st exit onto London Road/A20 and then turn right onto Maidstone Road/A25. Continue to follow A25 for 2.5 miles and at the roundabout, take the 2nd exit onto Borough Green Road/A227, continue onto the High Street and the hotel will be on the left. If you are travelling by train: Tonbridge railway station is the closest to the hotel, ½ mile away. Accommodation Rose and Crown Hotel, Tonbridge The Best Western Rose & Crown Hotel in the heart of Tonbridge is full of old-world charm. Opposite Tonbridge Castle, it offers traditional hospitality, with the warmest of welcomes guaranteed. Retaining the unique feel of the original building, you’ll be treated to oak beams and Jacobean panels, while all renovations and extensions have been sympathetic to the its original design. Facilities include a bar and restaurant. Each of the bedrooms feature TV, radio, telephone and tea and coffee making facilities. There is free parking on-site. Additional details can be found via the hotel website: https://www.bestwestern.co.uk/hotels/best-western-rose-and-crown-hotel-83792 Check-in and departure from the hotel On the day of arrival you will be able to check-in at the hotel from 14.00, and the tour manager will meet you in the evening at the welcome reception. -

Liste Des Elus Du Departement De Seine-Maritime

LISTE DES ELUS DU DEPARTEMENT DE SEINE-MARITIME CANTON QUALITE COLLEGE NOM PRENOM MANDATAIRE CP VILLE 01 ARGUEIL TITULAIRE 1 BELLET MARC 76780 LA HALLOTIERE 01 ARGUEIL TITULAIRE 1 BULEUX FRANCOISE 76780 NOLLEVAL 01 ARGUEIL SUPPLEANT 1 CAGNIARD PHILIPPE 76780 SIGY EN BRAY 01 ARGUEIL SUPPLEANT 1 DOMONT LYDIE 76780 SIGY EN BRAY 01 ARGUEIL TITULAIRE 1 GRISEL JEROME 76780 LE MESNIL LIEUBRAY 01 ARGUEIL SUPPLEANT 1 LANCEA PHILIPPE 76220 LA FEUILLIE 01 ARGUEIL SUPPLEANT 1 LETELLIER JEAN-PIERRE 76780 SIGY EN BRAY 01 ARGUEIL TITULAIRE 1 ROHAUT ARMELLE 76780 LA CHAPELLE ST OUEN 02 AUMALE TITULAIRE 1 AVYN SANDRINE 76390 RICHEMONT 02 AUMALE TITULAIRE 1 CHAIDRON GERARD 76390 ELLECOURT 02 AUMALE SUPPLEANT 1 CHOQUART CHRISTOPHE 76390 VIEUX ROUEN SUR BRESLE 02 AUMALE SUPPLEANT 1 COOLS CHRISTOPHE 76390 CONTEVILLE 02 AUMALE TITULAIRE 1 FERON YOLAINE 76390 CONTEVILLE 02 AUMALE SUPPLEANT 1 PINGUET JEAN-JACQUES 76390 CONTEVILLE 02 AUMALE TITULAIRE 1 POULET NICOLAS 76390 CONTEVILLE 02 AUMALE SUPPLEANT 1 VATTIER JACQUES 76390 RICHEMONT 03 BACQUEVILLE EN CAUX TITULAIRE 1 AUBLE CHRISTINE 76730 AVREMESNIL 03 BACQUEVILLE EN CAUX SUPPLEANT 1 LEVASSEUR BRIGITTE 76730 AVREMESNIL 03 BACQUEVILLE EN CAUX TITULAIRE 1 MASSE STEPHANE 76730 BACQUEVILLE EN CAUX 03 BACQUEVILLE EN CAUX TITULAIRE 1 VAILLANT GERALDINE 76730 AUPPEGARD 03 BACQUEVILLE EN CAUX SUPPLEANT 1 VASSEUR JEAN-BAPTISTE 76730 BACQUEVILLE EN CAUX 03 BACQUEVILLE EN CAUX SUPPLEANT 1 VIARD MARIE-PAULE 76730 AUPPEGARD 04 BELLENCOMBRE SUPPLEANT 1 BARRE GILLES 76680 BELLENCOMBRE 04 BELLENCOMBRE SUPPLEANT 1 DEHONDT -

Dives Sur Mer, Le 23 Juillet 2020 a L'attention Des Conseillers

Le Président Dives sur Mer, le 23 juillet 2020 A l’attention des conseillers communautaires Liste des destinataires in fine Mesdames, Messieurs les Conseillers et chers collègues, La prochaine réunion du conseil communautaire de Normandie-Cabourg-Pays d’Auge se déroulera en présentiel le : Jeudi 30 juillet 2020 à 17h00 Espace Nelson Mandela A Dives sur Mer A NOTER : ➢ Dans ce contexte de crise sanitaire, veuillez-vous munir d’un masque et d’un stylo personnel ➢ En cas d’indisponibilité vous pouvez donner ou recevoir 2 pouvoirs, ces pouvoirs doivent être déposés ou transmis avant la réunion (dans le cas contraire il n’en sera pas pris compte) ➢ La séance ne sera pas ouverte au public L’ordre du jour est le suivant : - Compte rendu conseil communautaire du 16 juillet 2020 ; - Annonce des dernières décisions du Président ; 1- Délégation de pouvoir au Président, vice-présidents, membres du bureau ; 2- Election des membres de la commission d’appel d’offres (CAO) ; 3- Election des membres de la Commission Locale d’Evaluation des Charges Transférées (CLECT) ; 4- Modification des statuts de l'EPIC Office de Tourisme Intercommunal ; 5- Election au Comité de direction de l’EPIC Office de Tourisme Intercommunal ; 6- Election d’un représentant à la Mission Locale Caen la Mer Calvados Centre ; 7- Election des délégués au bureau du Pôle Métropolitain Caen Normandie Métropole ; 8- Election de représentants au GAL LEADER ; 9- Election de représentants au Syndicat pour la Valorisation et l'Elimination des Déchets ménagers de l'Agglomération Caennaise -

Plan De Prévention Des Risques Littoraux De L'estuaire De La Dives Note De Présentation

PRÉFET DU CALVADOS PLAN DE PREVENTION DES RISQUES LITTORAUX DE L’ESTUAIRE DE LA DIVES Communes de Cabourg, de Dives-sur-mer, de Périers-en-Auge et de Varaville Note de présentation Direction Départementale des Territoires et de la Mer du Calvados L R P P Plan de prévention des risques littoraux de l'estuaire de la Dives Note de présentation SOMMAIRE I. PRÉAMBULE................................................................................................................................9 I.1. Modalités de lecture du document.....................................................................................9 I.2. Les fondements de la politique de l’État en matière de risques naturels majeurs......10 I.2.1. Définition du risque...................................................................................................10 I.2.2. Les textes fondateurs................................................................................................10 I.3. Les plans de prévention des risques naturels prévisibles.............................................11 I.4. La responsabilité des acteurs en matière de prévention...............................................13 I.4.1. La responsabilité de l’État.........................................................................................14 I.4.2. La responsabilité des Collectivités..........................................................................14 I.4.3. La responsabilité du citoyen.....................................................................................15 I.4.4. -

The Bayeux Tapestry

The Bayeux Tapestry The Bayeux Tapestry A Critically Annotated Bibliography John F. Szabo Nicholas E. Kuefler ROWMAN & LITTLEFIELD Lanham • Boulder • New York • London Published by Rowman & Littlefield A wholly owned subsidiary of The Rowman & Littlefield Publishing Group, Inc. 4501 Forbes Boulevard, Suite 200, Lanham, Maryland 20706 www.rowman.com Unit A, Whitacre Mews, 26-34 Stannary Street, London SE11 4AB Copyright © 2015 by John F. Szabo and Nicholas E. Kuefler All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any electronic or mechanical means, including information storage and retrieval systems, without written permission from the publisher, except by a reviewer who may quote passages in a review. British Library Cataloguing in Publication Information Available Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Szabo, John F., 1968– The Bayeux Tapestry : a critically annotated bibliography / John F. Szabo, Nicholas E. Kuefler. pages cm Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-1-4422-5155-7 (cloth : alk. paper) – ISBN 978-1-4422-5156-4 (ebook) 1. Bayeux tapestry–Bibliography. 2. Great Britain–History–William I, 1066–1087– Bibliography. 3. Hastings, Battle of, England, 1066, in art–Bibliography. I. Kuefler, Nicholas E. II. Title. Z7914.T3S93 2015 [NK3049.B3] 016.74644’204330942–dc23 2015005537 ™ The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of American National Standard for Information Sciences—Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992. Printed -

University of Southampton Research Repository Eprints Soton

University of Southampton Research Repository ePrints Soton Copyright © and Moral Rights for this thesis are retained by the author and/or other copyright owners. A copy can be downloaded for personal non-commercial research or study, without prior permission or charge. This thesis cannot be reproduced or quoted extensively from without first obtaining permission in writing from the copyright holder/s. The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holders. When referring to this work, full bibliographic details including the author, title, awarding institution and date of the thesis must be given e.g. AUTHOR (year of submission) "Full thesis title", University of Southampton, name of the University School or Department, PhD Thesis, pagination http://eprints.soton.ac.uk i UNIVERSITY OF SOUTHAMPTON FACULTY OF HUMANITIES School of History The Wydeviles 1066-1503 A Re-assessment by Lynda J. Pidgeon Thesis for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy 15 December 2011 ii iii ABSTRACT Who were the Wydeviles? The family arrived with the Conqueror in 1066. As followers in the Conqueror’s army the Wydeviles rose through service with the Mowbray family. If we accept the definition given by Crouch and Turner for a brief period of time the Wydeviles qualified as barons in the twelfth century. This position was not maintained. By the thirteenth century the family had split into two distinct branches. The senior line settled in Yorkshire while the junior branch settled in Northamptonshire. The junior branch of the family gradually rose to prominence in the county through service as escheator, sheriff and knight of the shire. -

Trees, Intestines and William the Conqueror*

TREES, INTESTINES AND WILLIAM THE CONQUEROR* İSLAM KAVAS** Before modern times, a ruler needed more than election in order to get public approval. It was supposed to be proved that ruling was a certain destiny for the ruler by blood or divine approval. The Normans, especially after they conquered and began to rule England in 1066, needed legitimacy as well. Some Norman chronicles used dreams and prophecy, as did many other dynasties’ chronicles.1 The current study will focus on the dream of Herleva, mother of William the Conqueror, its content, and its meaning. The accounts of William of Malmesbury, Wace, and Benoît de Saint-Maure will be the sources for the dream. I will argue that the dream of Herleva itself and its content are not related randomly. They have a function and a meaning aff ected by historical background of Europe. According to the chronicle sources, Herleva or Arlette, was a daughter of a burgess2 and a pollincter, who prepared corpses for burial, named Fulbert.3 She was living at Falaise where William was born in 1027-1028.4 She immediately attrac- ted Robert, William’s father, as soon as they met. Robert took her to his bed. One of these occasions was special because Herleva had an exceptional dream. This dream was about their future son, William the Conqueror. The dream of Herleva is transmitted to us through three diff erent versions * This article is supported by The Scientifi c and Technological Research Council of Turkey. ** Dr., Eskişehir Osmangazi University, Faculty of Science and Letters, Department of History, Eskişehir/TURKEY, [email protected] 1 The writer works on a comperative history of founding dreams and this paper is a part of this work.