A Vernacular Anglo-Norman Chronicle from Thirteenth- Century Ireland*

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

HISTORY of ABERYSTWYTH

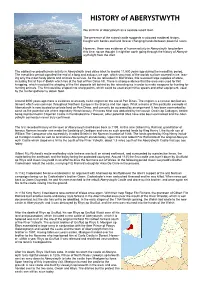

HISTORY of ABERYSTWYTH We all think of Aberystwyth as a seaside resort town. The presence of the ruined castle suggests a coloured medieval history, fraught with battles and land forever changing hands between powerful rulers. However, there was evidence of human activity in Aberystwyth long before this time, so we thought it might be worth going through the history of Aberyst- wyth right from the start. The earliest recorded human activity in Aberystwyth area dates back to around 11,500 years ago during the mesolithic period. The mesolithic period signalled the end of a long and arduous ice age, which saw most of the worlds surface covered in ice, leav- ing only the most hardy plants and animals to survive. As the ice retreaded in Mid Wales, this revealed large supplies of stone, including flint at Tan-Y-Bwlch which lies at the foot of Pen Dinas hill. There is strong evidence that the area was used for flint knapping, which involved the shaping of the flint deposits left behind by the retreating ice in order to make weapons for hunting for hunting animals. The flint could be shaped into sharp points, which could be used as primitive spears and other equipment, used by the hunter gatherer to obtain food. Around 3000 years ago there is evidence of an early Celtic ringfort on the site of Pen Dinas. The ringfort is a circular fortified set- tlement which was common throughout Northern Europe in the Bronze and Iron ages. What remains of this particular example at Aberystwyth is now located on private land on Pen Dinas, and can only be accessed by arrangement. -

Tonbridge Castle and Its Lords

Archaeologia Cantiana Vol. 16 1886 TONBRIDGE OASTLE AND ITS LORDS. BY J. F. WADMORE, A.R.I.B.A. ALTHOUGH we may gain much, useful information from Lambard, Hasted, Furley, and others, who have written on this subject, yet I venture to think that there are historical points and features in connection with this building, and the remarkable mound within it, which will be found fresh and interesting. I propose therefore to give an account of the mound and castle, as far as may be from pre-historic times, in connection with the Lords of the Castle and its successive owners. THE MOUND. Some years since, Dr. Fleming, who then resided at the castle, discovered on the mound a coin of Con- stantine, minted at Treves. Few will be disposed to dispute the inference, that the mound existed pre- viously to the coins resting upon it. We must not, however, hastily assume that the mound is of Roman origin, either as regards date or construction. The numerous earthworks and camps which are even now to be found scattered over the British islands are mainly of pre-historic date, although some mounds may be considered Saxon, and others Danish. Many are even now familiarly spoken of as Caesar's or Vespa- sian's camps, like those at East Hampstead (Berks), Folkestone, Amesbury, and Bensbury at Wimbledon. Yet these are in no case to be confounded with Roman TONBEIDGHE CASTLE AND ITS LORDS. 13 camps, which in the times of the Consulate were always square, although under the Emperors both square and oblong shapes were used.* These British camps or burys are of all shapes and sizes, taking their form and configuration from the hill-tops on which they were generally placed. -

Information on This Tour

1066 And All That Travel The tour starts and finishes at the Rose and Crown Hotel, Tonbridge 125 High Street, Tonbridge TN9 1DD United Kingdom Tel: +44 (0)3330 034292 Please note that transport to the hotel is not included in the price of the tour. Transport Driving directions to the hotel: Take exit 2A from M26, A20 to A25/A227, and follow the A227 to Tonbridge High Street. At the roundabout, take the 1st exit onto London Road/A20 and then turn right onto Maidstone Road/A25. Continue to follow A25 for 2.5 miles and at the roundabout, take the 2nd exit onto Borough Green Road/A227, continue onto the High Street and the hotel will be on the left. If you are travelling by train: Tonbridge railway station is the closest to the hotel, ½ mile away. Accommodation Rose and Crown Hotel, Tonbridge The Best Western Rose & Crown Hotel in the heart of Tonbridge is full of old-world charm. Opposite Tonbridge Castle, it offers traditional hospitality, with the warmest of welcomes guaranteed. Retaining the unique feel of the original building, you’ll be treated to oak beams and Jacobean panels, while all renovations and extensions have been sympathetic to the its original design. Facilities include a bar and restaurant. Each of the bedrooms feature TV, radio, telephone and tea and coffee making facilities. There is free parking on-site. Additional details can be found via the hotel website: https://www.bestwestern.co.uk/hotels/best-western-rose-and-crown-hotel-83792 Check-in and departure from the hotel On the day of arrival you will be able to check-in at the hotel from 14.00, and the tour manager will meet you in the evening at the welcome reception. -

William Marshal and Isabel De Clare

The Marshals and Ireland © Catherine A. Armstrong June 2007 1 The Marshals and Ireland In the fall of 1947 H. G. Leaske discovered a slab in the graveyard of the church of St. Mary‟s in New Ross during the repair works to the church (“A Cenotaph of Strongbow‟s Daughter at New Ross” 65). The slab was some eight feet by one foot and bore an incomplete inscription, Isabel Laegn. Since the only Isabel of Leinster was Isabel de Clare, daughter of Richard Strongbow de Clare and Eve MacMurchada, it must be the cenotaph of Isabel wife of William Marshal, earl of Pembroke. Leaske posits the theory that this may not be simply a commemorative marker; he suggests that this cenotaph from St Mary‟s might contain the heart of Isabel de Clare. Though Isabel died in England March 9, 1220, she may have asked that her heart be brought home to Ireland and be buried in the church which was founded by Isabel and her husband (“A Cenotaph of Strongbow‟s Daughter at New Ross” 65, 67, 67 f 7). It would seem right and proper that Isabel de Clare brought her life full circle and that the heart of this beautiful lady should rest in the land of her birth. More than eight hundred years ago Isabel de Clare was born in the lordship of Leinster in Ireland. By a quirk of fate or destiny‟s hand, she would become a pivotal figure in the medieval history of Ireland, England, Wales, and Normandy. Isabel was born between the years of 1171 and 1175; she was the daughter and sole heir of Richard Strongbow de Clare and Eve MacMurchada. -

Corrections to Domesday Descendants As Discussed by the Society/Genealogy/Medieval Newsgroup

DOMESDAY DESCENDANTS SOME CORRIGENDA By K. S. B. KEATS-ROHAN Bigod, Willelm and Bigod comes, Hugo were full brothers. Delete ‘half-brother’. de Brisete, Jordan Son of Ralph fitz Brien, a Domesday tenant of the bishop of London. He founded priories of St John and St Mary at Clerkenwell during the reign of Stephen. He married Muriel de Munteni, by whom he had four daughters, Lecia wife of Henry Foliot, Emma wife of Rainald of Ginges, Matilda, a nun of Clerkenwell, and Roesia. After his death c. 1150 his widow married secondly Maurice son of Robert of Totham (q.v.). Pamela Taylor, ‘Clerkenwell and the Religious Foundations of Jordan de Bricett: A Re-examination’, Historical Research 63 (1990). de Gorham, Gaufrid Geoffrey de Gorham held, with Agnes de Montpincon or her son Ralph, one fee of St Albans abbey in 1166. Kinsman of abbots Geoffrey and Robert de Gorron. Abbot Geoffrey de Goron of St Albans built a hall at Westwick for his brother-in-law Hugh fitz Humbold, whose successors Ivo and Geoffrey used the name de Gorham (GASA i, p. 95). Geoffrey brother of Abbot Robert and Henry son of Geoffrey de Goram attested a charter of Archdeacon John of Durham c. 1163/6 (Kemp, Archidiaconal Acta, 31). Geoffrey’s successor Henry de Gorhan of Westwick (now Gorhambury) held in 1210 (RBE 558). VCH ii, 393. de Mandeville, Willelm Son of Geoffrey I de Mandeville of Pleshy, Essex, whom he succeeded c. 1100. He also succeeded his father as constable of the Tower of London, and office that led to his undoing when Ranulf, bishop of Durham, escaped from his custody in 1101. -

THE MISSING EARL: RICHARD FITZALAN, EARL of ARUNDEL and SURREY, and the ORDER of the GARTER Michael Burtscher

Third Series Vol. III part 2. ISSN 0010-003X No. 214 Price £12.00 Autumn 2007 THE COAT OF ARMS an heraldic journal published twice yearly by The Heraldry Society THE COAT OF ARMS The journal of the Heraldry Society Third series Volume III 2007 Part 2 Number 214 in the original series started in 1952 The Coat of Arms is published twice a year by The Heraldry Society, whose registered office is 53 High Street, Burnham, Slough SL1 7JX. The Society was registered in England in 1956 as registered charity no. 241456. Founding Editor †John Brooke-Little, C.V.O., M.A., F.H.S. Honorary Editors C. E. A. Cheesman, M.A., PH.D., Rouge Dragon Pursuivant M. P. D. O’Donoghue, M.A., Bluemantle Pursuivant Editorial Committee Adrian Ailes, B.A., F.S.A., F.H.S. Jackson W. Armstrong, B.A. Andrew Hanham, B.A., PH.D. Advertizing Manager John Tunesi of Liongam THE COAT OF ARMS THE MISSING EARL: RICHARD FITZALAN, EARL OF ARUNDEL AND SURREY, AND THE ORDER OF THE GARTER Michael Burtscher The omission of Richard Fitzalan, Earl of Arundel and Surrey (c.1307-1376) from the Order of Garter has always been regarded with great puzzlement by historians.1 More so because, in 1344, Arundel was chosen to be part of Edward III’s new projects to refound the Arthurian Round Table; a project which had its origins in the political crisis of 1340-41 as a reconciliatory body to mend the wounds left by the crisis and as a galvanising element in the Anglo-French conflict. -

The Place of the Honour in Twelfth-Century Society

THE PLACE OF THE HONOUR IN TWELFTH-CENTURY SOCIETY: THE HONOUR OF CLARE 1066- 1217 byJENNIFERC.WARD,MA.,PI-I.D LACKOFEVIDENCEbetweenthe Domesday Survey and the late 12th century can often make it difficultto study feudal and baronial development in England. In Suffolk,however, it is particularly fortunate that sufficientsource material survivesfor it to be possibleto trace the extremely complex and changing structure of one of the most important honours in the county, the honour of Clare, throughout the 12th century. The honour, comprising extensive lands in north-west Essex and west Suffolk, was granted by William the Conqueror to the founder of the Clare family, Richard son of Count Gilbert of Brionne;' in 1086 the demesne holdings in these two counties, together with outlying estates in Hertfordshire, Middlesex, Cambridgeshire and Huntingdonshire which were later regarded as part of the honour, amounted in value to just over £400, and the subinfeudated land to about £185. Richard also held lands in Kent and Surrey which were centred on Tonbridge; his demesne holdings in these two counties were valued at nearly £190, and the subinfeudated land at about £160. There was no doubt even in 1086 that Clare would be-the main family centre, and Clare, rather than Tonbridge, became the family name in the early 12th century. The wealth and importance of Clare became even more marked when the Norfolk estates of Rainald son of Ivo, worth about £115 in 1086, were added to the honour, probably in the reign of Henry I. Admittedly little is known of the Clare demesne manors in the 12th century, but the cartulary of the priory of Stoke by Clare, which was essentially the honorial monastery, provides detailed material not only on officialsand sub-tenants but alsoon the relationship between lord and vassals.' Taken together with Domesday Book and charter evidence, and the Cartaof 1166 (the reply to Henry II's enquiry into the number of knights' fees on each honour), it shows clearly that at no point in the 12th century can the honour and its organisation be described as static. -

THE LADIES De CLARE & the POLITICS of the 14Th CENTURY

THE LADIES de CLARE & THE POLITICS OF THE 14th CENTURY lot has been written about the Despenser’s and Piers Gaveston (who even has a ‘secret’ Society named after him), so it seems pointless repeating much of it here, but I have often A wondered what their wives, Eleanor and Margaret de Clare thought of what their respective husbands were up to, and whether the two sisters ever met to discuss their plight whilst they were near neighbours at Woking and Byfleet? Eleanor de Clare was the eldest daughter of Eleanor was a great favourite of her uncle, The Coat of Arms of Gilbert de Clare (the 6th Earl of Hertford, 7th Earl Edward II, who apparently ‘paid her living Gilbert de Clare, 7th of Gloucester and Lord of Glamorgan), and his expenses throughout his reign’, with payments Earl of Hertford, 8th second wife Joan of Acre, who was the daughter being made from the Royal Wardrobe accounts Earl of Gloucester. of Edward I and Eleanor of Castile. She was for clothes and other items – a privilege that born in 1292 at Caerphilly Castle and in 1306 even his two sisters didn’t enjoy! She was the at the age of thirteen or fourteen was married principal lady-in-waiting to Queen Isabella and to Hugh le Despenser the Younger when he was even had her own retinue, headed by her own Countess of Cornwall. Instead Edward II gave about twenty. chamberlain, John de Berkenhamstead. her Oakham Castle and from 1313 to 1316 she was High Sheriff of Rutland. As a grand-daughter of Edward I she was Margaret de Clare was the second eldest de obviously quite a catch for the Younger Clare daughter. -

A Study of Anglo-Saxon and Anglo-Norman Noble Women

DAUGHTERS, WIVES, AND WIDOWS: A STUDY OF ANGLO-SAXON AND ANGLO-NORMAN NOBLE WOMEN Paula J. Bailey, M.S.E. Candidate Mentor: Ann Smith, Ph.D., Professor of History Abstract Traditional medieval histories have tended to downplay the role of noble women in early medieval England. However, increasingly popular gender studies in the last twenty years have prompted a renewed interest by scholars eager to make up for lost time and assign women a more significant role. In light of these efforts, research now indicates Anglo-Saxon women not only had considerable independence regarding land ownership, but they could also dispose of property at will. By contrast, noble women of the Anglo-Norman period appeared, at first glance, not to have fared as well as their Anglo-Saxon predecessors. A closer study, however, reveals that these later women not only held their own honor courts, supervised households and educated their children, but, when the need arose, helped defend their homes. In the military- based society of Anglo-Norman England, noble women were also needed to produce legitimate heirs. Wives, daughters, and widows in the Anglo-Saxon and Norman English world were not on the fringes of society. Introduction Scholars interested in gender studies have made great progress over the last twenty years researching and writing about medieval English women. Traditional histories had, until recently, slighted noble women and their contributions to early Anglo-Saxon society with claims that they played only a nominal role. Historians now conclude that, to the contrary, Anglo-Saxon noble women were relatively independent through their land-holding rights while, by contrast, later Anglo-Norman noble women lost some independence when land ownership became closely associated with the new military-based society that followed the Norman Conquest in 1066. -

344 History and Antiquities of Leicestershire

344 HISTORY AND ANTIQUITIES OF LEICESTERSHIRE. II. GILBERT, earl of ANGIE, or EWE, in Normandy.^ .... III- WILUAM THE=pMaud, dau. of Baldwin- , — ' CONQUEROR33. J 5thearl of Flanders, fur-' Richard , son of Gilbert, came into England with the Conqueror, 1066. named The Gentle , s— _J ,- 1 Gilbert Fitz Richard "', son and heir, first=pAdeliza, dau. of Henry, the first of the name, king of England earl of Clare, died 1152. Cleremont. youngest son, died Dec. 1, 1135. Richard Fitz Gilbert 3, 2d earl of Clare,=pAdeliza, sister of Robert Consul, earl of=p dau. of Robert Fitz and lord of Tunbridge, in Kent; I Randulph carl Gloucester 3', base son. Hammond, lord of Car- died 1156. j of Chester. boile in Normandy. 1. Gilbert24, earl of 2- Roger de Clare26, brother and=pMaud, dau. and William Consu!,=pHawifia, dau. of Clare and Here- heir of Gilbert, was earl of Clare I heir of James earl of Glou- Rob. Bossu, earl ford, died s. p. and Hereford ; died 1174. St. Hillary. cester. of Leicester. 1 — ' Richard '*, earl of Clare and Here-=pAmicia, 2d dau. and Mabell, eldest dau. and Isabel, 3d=pjohn, 4th son of king ford/" 1, die1*1 d 1218f^ , and1 was 1*burie1 d coheir1* , was1 burie' 1d " in coheir1" , marr. AAlmeril * c 1dau . an1d I f Hen.llT T 1 . earT l of* fv~ > Glou• ^~^ - in the priory or Tunbridge. Tunbridge priory. de Montfort, earl of coheir. | cester in right of his Evreux in Normandy. I wife. 1 1 Gilbert de Clare27, earl=^=lfabel, 3d dau. of William Marshal the Walter de Burgh, earl of Ulster m right of of Gloucester and elder, sister and coheir of Anselm earl his wife, heir of Hugh Fortibus, earl of Hereford. -

Regesta Regum Anglo-Normannorum, 1066-1154

:CD ;00 100 •OJ !oo CjD oo /!^ REGESTA WILLELMI CONQUESTORIS ET WILLELMI RUFI 1066-1100 OXFORD UNIVERSITY PRESS LONDON EDINBURGH GLASGOW NEW YORK TORONTO MELBOURNE BOMBAY HUMPHREY MILFORD M.A. PUBHSHER TO THE UNIVERSITY REGESTA REGUM ANGLO -NORMANNORUM 1066-1154 VOLUME I REGESTA WILLELMI CONQUESTORIS ET WILLELMI RUFI 1066-1100 EDITED VVITH INTRODUCTIONS NOTES AND INDEXES BY H. W. C. DAVIS, M.A. FELLOW AND TUTOR OF BALLIOL COLLEGE, OXFORD SOiAIETIME FELLOW OF ALL SOULS COLLEGE WITH THE ASSISTANCE OF R J. WHITWELL, B.Litt. OXFORD AT THE CLARENDON PRESS M UCCCC XIII 190 J)37 Y.l PREFACE This is the first of three volumes covering the period of the Anglo-Norman kings (1066-1154). The second and third volumes are far advanced, and will shortly be in the press. The object of ^ the series is to give a calendar, chronologically arranged and the of critically annotated, of the royal acts of period, and some cognate documents which are valuable for the historian. The first care of the editor has been to call attention to materials which iUustrate the development of law and institutions. But the interests of the genealogist and the topographer have not been neglected. Pains have been taken to record the names of persons, and the more important names of places, which are mentioned in the docu- ments. The collection includes charters issued in and for Normandy. Norman archives have not been searched for the purpose, since the Norman material is being coUected by Professor Haskins. But it seemed advisable to calendar such Norman charters as have been or are to be found in for of printed EngUsh manuscripts ; many these charters throw useful sideUghts upon EngUsh history. -

Ln M M I T E

f h " " Ln m m I t e. Cams um ov m o x g h ) C O N Q U E EN C O MP A N I S O N S . 9 Q q 3 6 8 W m ] c 3 0 x 9 “ J Rs? LAN O . HE , pl s mn lg' H A o ne r ER LD . W e find but few historians of all ag es wh o hav e been dilig ent in their ea c for t u It is t ei c ommon m et s r h r th. h r hod to tak e on tru st e dls tu b ute to th e P u blic b w ic mea a fal e oo o c e ec eiv e f om m od , y h h ns s h d n r d r a ” — t a itio al to o te it . DR YDEN C h a racter P ol bius. r d n p s r y , Qf y IN T W O VO L ME U S . VOL . II . g V <1; TINSLEY BROTHERS 8 CATHERINE S S ND , , TREET, TRA . C ONTENTS . CH AP TE R I. PAGE ’ ou de e of o o — u d Av ranch es E of Ra l Ga l , Earl N rf lk H gh , arl — e te eof e de Mowbra o of ou ce —Ro e Ch s r G fr y _ y, Bish p C tan s g r de Mowbray (his brother) CH A PT E R II.