Herst CASTLE: Julia Morgan Was Enthralled with Mathematics and Physics in High School

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Women Architects

E-Newsletter | May 2012 Women Architects What do the Hearst Castle in California and many of the buildings in Grand Canyon National Park have in common? They were designed by women architects! In this month's newsletter, we feature two early women architects - Julia Morgan and Mary Colter. California's first licensed woman architect, Julia Morgan, studied architecture in Paris. After failing the entrance examination to the École des Beaux-Arts twice, she learned that the faculty had failed her deliberately to discourage her admission. Undeterred, she gained admission and received her certificate in architecture in 1902. By 1904, she had opened her own architecture practice in San Francisco. After receiving acclaim when one of her buildings on the Mills College campus withstood the 1906 San Francisco earthquake, she was commissioned to rebuild the damaged Fairmont Hotel. With this project Morgan's reputation as well as her architecture practice was assured. Julia Morgan Morgan designed her first building for the YWCA in Oakland in 1912. She then began work on the YWCA's seaside retreat Asilomar, near Monterey, which has hosted thousands of visitors since its founding in 1913. Today Asilomar is a state historical park. Morgan's work on the Hearst Castle, which is also now a state historical monument, cemented her reputation. The Castle, located at San Simeon, has attracted more than 35 million visitors since it opened to the public in 1958. Architect Mary Colter was asked by railroad magnate Fred Harvey to design hotels and restaurants along the Santa Fe Railway route, with the objective of bringing tourists to the southwestern United States. -

Y\5$ in History

THE GARGOYLES OF SAN FRANCISCO: MEDIEVALIST ARCHITECTURE IN NORTHERN CALIFORNIA 1900-1940 A thesis submitted to the faculty of San Francisco State University A5 In partial fulfillment of The Requirements for The Degree Mi ST Master of Arts . Y\5$ In History by James Harvey Mitchell, Jr. San Francisco, California May, 2016 Copyright by James Harvey Mitchell, Jr. 2016 CERTIFICATION OF APPROVAL I certify that I have read The Gargoyles of San Francisco: Medievalist Architecture in Northern California 1900-1940 by James Harvey Mitchell, Jr., and that in my opinion this work meets the criteria for approving a thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Master of Arts in History at San Francisco State University. <2 . d. rbel Rodriguez, lessor of History Philip Dreyfus Professor of History THE GARGOYLES OF SAN FRANCISCO: MEDIEVALIST ARCHITECTURE IN NORTHERN CALIFORNIA 1900-1940 James Harvey Mitchell, Jr. San Francisco, California 2016 After the fire and earthquake of 1906, the reconstruction of San Francisco initiated a profusion of neo-Gothic churches, public buildings and residential architecture. This thesis examines the development from the novel perspective of medievalism—the study of the Middle Ages as an imaginative construct in western society after their actual demise. It offers a selection of the best known neo-Gothic artifacts in the city, describes the technological innovations which distinguish them from the medievalist architecture of the nineteenth century, and shows the motivation for their creation. The significance of the California Arts and Crafts movement is explained, and profiles are offered of the two leading medievalist architects of the period, Bernard Maybeck and Julia Morgan. -

Forumjournal VOL

ForumJournal VOL. 32, NO. 2 “Every Story Told”: Centering Women’s History THIS ISSUE IS DEDICATED TO BOBBIE GREENE MCCARTHY AND KAREN NICKLESS. Gender, Race, and Class in the Work of Julia Morgan KAREN MCNEILL n June 22, 1972, architect Julia Morgan’s Hearst San Simeon State Historical Monument, also known as Hearst OCastle, was listed on the National Register of Historic Places. Since then, 19 more places—including approximately 26 buildings—that Morgan designed or was otherwise closely associated with have been listed individually or as part of historic districts. (Hearst Castle and Asilomar Conference Grounds are also National Historic Landmarks.) No fewer than 15 of those National Register properties are associated with organizations of, by, and for women, underscoring how closely the architect’s career was intertwined with the pre–World War II California women’s movement. This might suggest that Morgan’s legacy is well understood and that the spaces of women’s activism of Progressive Era California have been well documented and preserved in the landscape. But a closer look reveals significant gaps and weaknesses in our understanding of Julia Morgan’s career and its significance. It also exposes, more generally, the challenges of recognizing and preserving the history of gender and women—and other underrepresented groups—in the built environment, as well as the opportunities to improve. A VARIED BODY OF WORK No single building on the National Register could capture the breadth of Julia Morgan’s architectural significance, but when her contributions are considered collectively, certain themes emerge. Several properties—including St. John’s Presbyterian Church, Asilomar, the Sausalito Woman’s Club, and Girton Hall (now Julia Morgan Hall)—are excellent examples of the Bay Tradition style, an expression of the Arts and Crafts movement in the San Francisco/ Berkeley region. -

Julia Morgan Wyntoon and Other Hearst Projects 1933–1946

Julia Morgan Wyntoon and Other Hearst Projects 1933–1946 by Taylor Coffman AN OLD PHOTOGRAPH owned by Lynn Forney McMurray, a god- daughter of Julia Morgan, shows a large group of people at Wyntoon. Miss Morgan may be identifiable among them. Lynn thinks the photo dates from 1902 or ’03. It stems from the work being done on that northern California project by Bernard Maybeck for Phoebe Apperson Hearst. Julia Morgan, Lynn reasons, had recently returned from the Ecole des Beaux-Arts in Paris and was taking part in Wyntoon’s devel- opment under Maybeck. I’ve never confirmed Lynn’s theory, but it doesn’t seem far- fetched. Everyone knows that Maybeck had been a big influence on Morgan already and that they would keep interacting over the years ahead. However, no buildings are visible in the photo. The period de- picted, in any event, is that of the first-generation Wyntoon Castle—the medieval, Germanic pile that burned down in 1930. By then, at the outset of the thirties decade, Julia Morgan and W. R. Hearst had done some minor work at Wyntoon. In 1928, for in- stance, they built a swimming pool and two tennis courts. Hearst’s mother hadn’t left that property to him at her death in 1919. Instead, he had to persuade his cousin Anne Apperson Flint (a favorite of Phoebe Hearst’s) to sell him Wyntoon Castle in 1925—a point that’s neither here nor there where Morgan’s concerned. It merely means that the established Hearst-Morgan partnership, active at San Simeon since 1919, was at no liberty to do serious work at Wyntoon until the late 1920s. -

OF the UNIVERSITY of CALIFORNIA Editorial Board

OF THE UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA Editorial Board Rex W Adams Carroll Brentano Ray Cohig Steven Finacom J.R.K. Kantor Germaine LaBerge Ann Lage Kaarin Michaelsen Roberta J. Park William Roberts Janet Ruyle Volume 1 • Number 2 • Fall 1998 ^hfuj: The Chronicle of the University of California is published semiannually with the goal of present ing work on the history of the University to a scholarly and interested public. While the Chronicle welcomes unsolicited submissions, their acceptance is at the discretion of the editorial board. For further information or a copy of the Chronicle’s style sheet, please address: Chronicle c/o Carroll Brentano Center for Studies in Higher Education University of California, Berkeley, CA 94720-4650 E-mail [email protected] Subscriptions to the Chronicle are twenty-seven dollars per year for two issues. Single copies and back issues are fifteen dollars apiece (plus California state sales tax). Payment should be by check made to “UC Regents” and sent to the address above. The Chronicle of the University of California is published with the generous support of the Doreen B. Townsend Center for the Humanities, the Center for Studies in Higher Education, the Gradu ate Assembly, and The Bancroft Library, University of California, Berkeley, California. Copyright Chronicle of the University of California. ISSN 1097-6604 Graphic Design by Catherine Dinnean. Original cover design by Maria Wolf. Senior Women’s Pilgrimage on Campus, May 1925. University Archives. CHRONICLE OF THE UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA cHn ^ iL Fall 1998 LADIES BLUE AND GOLD Edited by Janet Ruyle CORA, JANE, & PHOEBE: FIN-DE-SIECLE PHILANTHROPY 1 J.R.K. -

BSC Owner's Manual

BSC Owner’s Manual Contact Information 2014 – 2015 BSC Central Office Welcome Co-opers! .................................................................................................. 4 2424 Ridge Road, Berkeley, CA 94709 510.848.1936 Fax: 510.848.2114 Moving In ................................................................................................................. 4 Hours: Monday - Friday, 10 - 5 History of the Cooperative Movement .................................................................... 8 www.bsc.coop The Rochdale Principles ............................................................................................. 9 History of the BSC ................................................................................................... 12 Policies ................................................................................................................... 13 Rights, Responsibilities & Rules ............................................................................... 14 Board of Directors: Cabinet Habitability Inspections ......................................................................................... 15 Spencer Hitchcock Zury Cendejas Dash Stander President VP of External Affairs Member-at-Large Building a Healthy Community ............................................................................... 17 [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] Emergencies ........................................................................................................... 19 Central Level Governance -

Jessica Blanche Peixotto and the Founding of Berkeley Social Welfare

Jessica Blanche Peixotto Revised May 29, 2020 1 Jessica Blanche Peixotto and the Founding of Berkeley Social Welfare Jeffrey L. Edleson, Ph.D.i University of California, Berkeley Abstract Jessica Blanche Peixotto was the first woman to become a full professor at the University of California in 1918 and yet her role in establishing social welfare studies at Berkeley is mostly untold. A social economist and foremost a scientist, she led efforts to infuse evidence-informed practice in professional social work education in the early 1900s, laying a foundation at Berkeley that is still felt today. Of her many efforts, she established a certificate in social welfare at Berkeley in 1917, the first such training on the West Coast. This article describes her personal and professional life and seeks to establish the importance of her role in establishing social work education at Berkeley and in furthering an evidence-informed approach to our professional work. Social work education began at the effective (Fischer, 1973). It has been the University of California in 1904 when academic home for Eileen Gambrill President Benjamin Ide Wheeler (2019, see Burnette, 2016), a member of appointed Dr. Jessica Blanche Peixotto as the Berkeley faculty for over four a lecturer in sociology. Despite being an decades and a leader in bringing alumnus of the School of Social Welfare evidence-informed practices to our field. at Berkeley and spending my entire This article draws on a wide variety career in social work higher education, I of sources published by and about was not aware of the historic importance Peixotto and her family. -

Julia Morgan Papers

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/kt9s2030pj Online items available Julia Morgan Papers Special Collections Robert E. Kennedy Library 1 Grand Avenue California Polytechnic State University San Luis Obispo, CA 93407 Phone: (805) 756-2305 Fax: (805) 756-5770 URL: http://www.lib.calpoly.edu/specialcollections/ Email: [email protected] © 1985, 2007 Trustees of the California State University. All rights reserved. Julia Morgan Papers MS 010 1 Julia Morgan Papers Special Collections Robert E. Kennedy Library Contact Information Special Collections Robert E. Kennedy Library California Polytechnic State University San Luis Obispo, CA 93407 Phone: 805/756-2305 Fax: 805/756-5770 Email: [email protected] URL: http://www.lib.calpoly.edu/specialcollections/ Processed by: Nancy Loe and Denise Fourie Date Completed: 2006, revised 2008 Encoded by: Byte Managers, 2006; Carina Love, 2007, 2008; Marisa Ramirez, 2009 © 1985, 2007 Trustees of the California State University. All rights reserved. Descriptive Summary Title: Julia Morgan Papers Date (inclusive): 1835-1958 (bulk 1896-1945) Date (bulk): Collection number: MS 010 Creator: Morgan, Julia, 1872-1957 Abstract: This collection contains architectural drawings and plans, office records, photographs, correspondence, project files, student work, family correspondence, and personal papers from the estate of California architect Julia Morgan, who practiced in San Francisco during the first half of the twentieth century. The bulk of the collection extends from 1896, when Morgan left for Paris to study architecture at the Beaux-Arts, to 1945 when her practice began to wind down. A persistent misperception exists that she destroyed records from her fifty-year practice when she retired in 1951. -

Julia Morgan ARCHITECT B

JULIA MORGAN ARCHITECT b. January 20, 1872 d. February 2, 1957 “My buildings will be my legacy … America’s first they will speak for me long after I’m gone.” independent female Julia Morgan is recognized as the first truly independent female architect in America architect, she is and the first female architect licensed by the state of California. She designed nearly best known for the 800 projects in California and Hawaii, including the famous Hearst Castle in San Simeon. Hearst Castle. Born in San Francisco and raised in Oakland, California, Morgan graduated from UC Berkeley with a degree in civil engineering. She was the only female engineer in her class. After Morgan received her bachelor’s degree, an instructor encouraged her to pursue architectural studies at École des Beaux-Arts in Paris. The school, which had never admitted a woman, initially refused her application. She was accepted eventually after reapplying and became the first female to graduate with a certificate in architecture. Upon graduation, Morgan returned to San Francisco and began working for John Galen Howard, a successful architect, on the University of California’s master plan. Morgan worked on designs for several buildings on the Berkeley campus and served as the primary designer of Berkley’s Hearst Greek Theater. In 1904 Morgan became the first woman to obtain an architecture license from the state of California and opened her own firm. She completed many notable commissions, including Phoebe Hearst’s Hacienda del Pozo de Verona in Pleasanton, California, and multiple buildings on the campus of Mills College. After the 1906 earthquake, Morgan was hired to repair the Fairmont Hotel in San Francisco. -

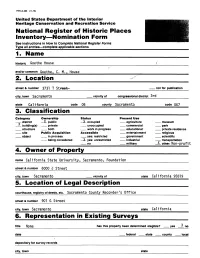

1. Name 6. Representation in Existing Surveys

FHR-8-300 (11-78) United States Department off the Interior Heritage Conservation and Recreation Service National Register of Historic Places Inventory — Nomination Form See instructions in How to Complete National Register Forms Type all entries — complete applicable sections _______________ 1. Name _________________ historic Goethe House _________________________ and/or common Goethe, C. M.» House ___________________ 2. Location - street & number 3731 T not for publication city, town Sacramento vicinity of congressional district 3rd state California code 06 county Sacramento code 067 3. Classification Category Ownership Status Present Use _^ district _ X_ public _ X_ occupied agriculture museum X building(s) private unoccupied commercial park structure both work in progress educational private residence site Public Acquisition Accessible entertainment religious object in process yes: restricted government scientific being considered _ X_ yes: unrestricted industrial transportation no military X other: Non-profit 4. Owner of Property name California State University, Sacramento, Foundation street & number 6000 J Street city, town Sacramento vicinity of state California 95819 5. Location of Legal Description courthouse, registry of deeds, etc. Sacramento County Recorder's Office street & number 901 G Street city, town Sacramento state California 6. Representation in Existing Surveys title None has this property been determined elegible? __ yes no date federal __ state __ county local depository for survey records city, town state 7. Description Condition Check one Check one excellent deteriorated unaltered x original site X good ruins X altered mrweri date fair unex posed Describe the present and original (iff known) physical appearance The Goethe House is a fine example of a Mediterranean Revival residence. -

A Partial Listing of Julia Morgan Buildings in CA Page 1

A Partial Listing of Julia Morgan Buildings in CA Page 1 Year Name of Building Type of Building ACityLAMEDA or Region 1912 1205 Bay Street Alameda Private Residence 1909 1232 Bay Street Alameda Private Residence 1909-10 1901 Central Ave Alameda Private Residence 1909-10 1315 Dayton Avenue Alameda Private Residence 1913 1025 Sherman Street Alameda Private Residence 1912 1121 Sherman Street Alameda Private Residence 1911 1326 Sherman Street Alameda Private Residence ACitySILOMAR or Region 1913 Pacific Grove Outside Inn Asilomar Community Center 1913 Asilomar Entrance Gates Asilomar Community Center 1913 Administration Building Asilomar Community Center 1915 Asilomar Chapel Asilomar Church 1915 Asilomar Guest Inn Asilomar Community Center 1915 Saltwater Swimming Pool Asilomar Community Center 1916 Visitors Lodge Asilomar Community Center 1918 Hilltop Cottage Asilomar Community Center 1918 Viewpoint Cottage Asilomar Community Center 1918 Crocker Dining Hall Asilomar Community Center 1923 Tide Inn Asilomar Community Center 1927-28 Pinecrest Asilomar Community Center 1927-28 Scripps Lodge Asilomar Community Center 1928 Merrill Hall Asilomar Community Center BCityERKELEY or Region 1918-1919 Berkeley Baptist Divinity School Berkeley School 1927 Berkeley Day Nursery auditorium Berkeley School 1918-19 Calvary Presbyterian Church Berkeley Church 1908-10 Saint John's Presbyterian Church Berkeley School 1924 Thousand Oaks Baptist Church Berkeley Church 1901-07 Hearst Mining Building Berkeley School 1903 Greek Theater Berkeley School 1903 Girton Hall Berkeley School 1925-26 Phoebe Hearst Gymnasium Berkeley School 1929-30 Berkeley Women's City Club Berkeley Club A Partial Listing of Julia Morgan Buildings in CA Page 2 Year Name of Building Type of Building 1923 Delta Zeta Sorority House Berkeley Club 1908 Kappa Alpha Theta Sorority House Berkeley Club 1904 Edmonds Apartment Building Berkeley Commercial Bldg. -

18888 Hayfield Court

State of California - The Resources Agency Primary # DEPARTMENT OF PARKS AND RECREATION HRI # PRIMARY RECORD Trinomial NRHP Status Code Other Listings Review Code Reviewer Date Page 1 of 4 *Resource Name or # (Assigned by recorder): Hayfield House P1. Other identifier: HP-88-01 (formerly 20235 La Paloma Ave.) *P2. Location: Not for Publication Unrestricted *a. County Santa Clara County and (P2b and P2c or P2d. Attach a location map as necessary.) *b. USGS 7.5' Quad Cupertino Date 1980 Photorevised T .8 S. ; R .1 W. ; Mount Diablo B.M. c. Address: 18888 Hayfield Ct. City Saratoga Zip 95070 d. UTM:(give more than one for large and/or linear resources) Zone 10S ; mE/ mN e.Other Locational Data: (e.g., parcel #, directions to resource, elevation, etc., as appropriate) Hayfield Court off Douglass Lane. APN# 397-24-104 *P3a. Description: (Describe resource and its major elements, include design, material, condition, alterations, size, setting, and boundaries) Renowned architect Julia Morgan designed this distinctive Tudor-Revival residence, located on a private road. City records and aerial views indicate that its complex roof is a primary character-defining feature. The main roof is a broad hip, with many gabled accent roofs and dormers providing rhythm and scale. The windows and French doors are multi-lite wood. The porch columns and the multiple flues on the chimneys provide some relief in the outsized scale. A distinctive oculus window punctuates each of the main front gables. This residence has a broad, horizontal composition associated with great Tudor house designs of the 1920s and a unique polished feeling associated with Morgan's work.