Repository EID Corporate Governance Failure of Cooperatives

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Dhl000ac Dhl000ad Dhl001ad Dhl000ae Dhl000ar Dhl001ar

Door handles Maneta escotilla Maniglie oblò Poignées de hublot Ручки люка ARCELIK ARISTON - INDESIT DHL000AC DHL001AR KIT White White Original code: 2813170100 Original code: 116576 ARDO ARISTON - INDESIT DHL000AD DHL002AR KIT KIT White White Original code: Original code: 719004000 049411 ARDO BOSCH - SIEMENS DHL001AD DHL000BO KIT White White Original code: Original code: 651027693 050099 055835 AEG BALAY - BOSCH - SIEMENS DHL000AE DHL000BY KIT Silver White Original code: 38823200 Original code: 069637 ARISTON - INDESIT BALAY - BOSCH - SIEMENS DHL000AR DHL001BY KIT White White Original code: Original code: 183607 141736 Door handles Maneta escotilla Maniglie oblò Poignées de hublot Ручки люка BALAY - BOSCH - SIEMENS FAGOR - BRANDT - OCEAN - SANGIORGIO DHL002BY DHL000FA White White Original code: Original code: 168839 52X1987 CANDY - ZEROWATT FAGOR - EDESA DHL000CY DHL001FA KIT White White Original code: Original code: LA8E0000L0 90447699 CANDY - ZEROWATT GORENJE DHL001CY DHL000GO KIT KIT White White Original code: Original code: 92676303 488137 CANDY - ZEROWATT GORENJE DHL002CY DHL001GO KIT KIT White Black Original code: Original code: 92676280 03010223 CANDY - ZEROWATT GORENJE - SIDEX DHL003CY DHL002GO KIT KIT White White Original code: Original code: 488119 49001136 03010354 Door handles Maneta escotilla Maniglie oblò Poignées de hublot Ручки люка GORENJE PHILCO DHL005GO DHL001PH KIT White White Original code: 112300177 Original code: 112300150 479300 032342 INDESIT - ARISTON SAN GIORGIO - BRANDT DHL000ID DHL000SG KIT White White Original -

ELEKTRO-SERVICE Alexander Zapla E.K. PDF-Katalog

ELEKTRO – SERVICE Alexander Zapla e.K. Untere Steinstr. 18 D-53604 Bad Honnef Tel. 02224 / 93550 Fax 02224 / 935555 www.eszapla-shop.de | [email protected] I N H A L T S V E R Z E I C H N I S Warengruppe Inhalt 00 Leitungen, Stecker, Verbinder 01 Dichtmaterial, Klebstoffe, Pflegemittel, Zubehör 02 Zu- und Ablaufschläuche, Zubehör, Abluftschläuche 03 Faltenbalge, Fenstermanschetten 04 Zulaufschläuche (Ventil-WM Einspülung-Bottich) 05 Ablaufschläuche (Bottich-Sieb-Pumpe-Auslauf) 06 GS-Gummidichtungen und GS-Teile 07 Luftschläuche, Bottichdichtungen u. Rückwand 08 Kochplatten, Heizflächen, Schalter 09 Ceranfelder 10 Spannringe, Schellen, Thermostat-Dichtungen 11 Heizungen f. Waschen, Trocknen, Kochen, Spülen 12 Dichtungen für Heizungen 13 Wassereinlauf - Ventile, E.-Dosierungen GS 14 Thermostate, Microthermsicherungen 15 Thermo.-Türschalter 16 Wippschalter, Schütze, Signallampen, Leuchtmittel 17 Kühl – Thermostate und Zubehör, allgemeines 18 Programmschaltwerk, Timer 19 Timerzubehör 20 Kondensatoren / Störschutzfilter 21 Laugen-, Umwälzpumpen, Lüftermotore u. Zubehör 22 Flusensiebe 23 Motoren 24 Motorkohlen, Keilriemenscheiben 25 Spannrollen, Keilriemen, Poly-V Riemen 26 Wellen- und Lagerdichtungen 27 Kugellager, Lagersätze, Trockner-Dichtungen 28 Stoßdämpfer / Reibungsdämpfer, Federbeine 29 Schleuderaufhängung, Stellfüße 30 Türglasrahmen, Türgläser 31 Türgriffe, Schließhaken, Türscharniere 32 WM-Einspülungen 33 Bedienungsknebel 98 Sanitär- und Wasserarmaturen Druckfehler, Irrtum, Preis und Lieferbarkeit vorbehalten. Ab einem Nettoauftragswert -

4F. EE21 Atlete II Presentation Nov2013 Presutto

EE21 Steering Committee, Geneva, 12-13 November 2013 State of the Art of the ATLETE II project update November 2013 Milena Presutto UTEE – Technical Unit Energy Efficiency The „ATLETE II“ project “ATLETE II”: Appliance Testing for Washing Machines Energy Label & Ecodesign Evaluation 11 partners from 8 Member States : • Italy: ISIS (co-ordinator), ENEA • Austria: AEA • Czech Republic: SEVEn • EU (Belgium): CECED, ECOS, ECEEE • France: ADEME • Germany: UniBonn • Sweden: SWEA • UK: ICRT Duration: 30 months (01/05/2012 – 30/10/2014) EC/partner financing input: 1.193.316,00 €/398.093,00 € 2 ATLETE II project structure WP 1 PROJECT MANAGEMENT BACKGROUND AND METHODOLOGICAL ASSESSMENT WP2 - MONITORING AND ASSESSEMENT WP3 - METHODOLOGY RE-ASSESSEMENT FIELD WORK PREPARATION FIELD WORK DEVELOPMENT WP4 WP6 LABORATORIES SELECTION APPLIANCES TESTING AND LABs CAPACITY BUILDING WP5 APPLIANCES SELECTION WP7 AND PURCHASING MSA NOTIFICATION AND FOLLOW UP WP8 FINAL OUTCOME DISCUSSION AND CONSOLIDATION WP 9 COMMUNICATION AND DISSEMINATION 3 ATLETE II project timetable 4 The „ATLETE II“ project goals Enhance and further promote the effectiveness of the EU energy labelling & ecodesign measures through : – identifying examples of effective enforcement of EU labelling & ecodesign legislation and national market surveillance – further addressing the issue of the feasibility and affordability of verification compliance testing on a new product – further upgrading and sharing of the verification procedure including the laboratories & appliance models selection – -

Open Research Online Oro.Open.Ac.Uk

Open Research Online The Open University’s repository of research publications and other research outputs Corporate governance as a key aspect in the failure of worker cooperatives Journal Item How to cite: Basterretxea, Imanol; Cornforth, Chris and Heras-Saizarbitoria, Inaki (2020). Corporate governance as a key aspect in the failure of worker cooperatives. Economic and Industrial Democracy (Early Access). For guidance on citations see FAQs. c 2020 The Author(s) Version: Accepted Manuscript Link(s) to article on publisher’s website: http://dx.doi.org/doi:10.1177/0143831X19899474 Copyright and Moral Rights for the articles on this site are retained by the individual authors and/or other copyright owners. For more information on Open Research Online’s data policy on reuse of materials please consult the policies page. oro.open.ac.uk Corporate governance as a key aspect in the failure of worker cooperatives Imanol Basterretxea* Department of Financial Economics Faculty of Economics and Business University of the Basque Country UPV-EHU [email protected] Chris Cornforth Department of Public Leadership and Social Enterprise. Open University Business School. [email protected] Iñaki Heras-Saizarbitoria Department of Management Faculty of Economics and Business University of the Basque Country UPV-EHU [email protected] This is the accepted version of the following article: Basterretxea, I.; Cornforth, C.; Heras-Saizarbitoria, I. (2020): Corporate governance as a key aspect in the failure of worker cooperatives. Economic and Industrial Democracy. [DOI: 10.1177/0143831X19899474 ] The copy-edited version is available at: https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/pdf/10.1177/0143831X19899474 1 Abstract: The article analyses governance difficulties at Fagor Electrodomésticos, for decades the world’s largest industrial cooperative, and sheds light on how the cooperative model and governance might have contributed to the firm’s bankruptcy. -

Presentation Appliances

CIMA S.p.A. INDEX 2 u Presentation of CIMABelfin Group u Our Vision (household appliance field) u Our Range of Products u Annual volume of product sold and Technology u Virtual Tours u New projects GLOBAL PRESENCE 3 VISION 4 To be the No. 1 in the Worldwide market for dampers and suspension springs production (household appliance) AABSAL Electrolux LGE Alladio F&P Little Swan Atlant Galanz Midea Beko Geli Miele Bosch General Electric Panasonic Candy Girbau Samha Chuangwei Haier Samsung Daewoo Hisense Sanyo Ebac IFB Vestel Edesa IT Wash - Sangiorgio Whirlpool RANGE OF PRODUCTS 5 SHOCK-ABSORBERS AND DAMPING SYSTEMS Dal 1946 ci proponiamo con successo quali partner attivi nello sviluppo di soluzioni CIMA, l’innovazione ci guida. intelligenti per l’elettrodomestico bianco con sistemi di sospensione, serraggio e fis- saggio per lavatrici. Qui sono illustrati alcu- ni significativi esempi di prodotti dedicati alle lavatrici domestiche ed industriali. RANGE OF PRODUCTS 6 SHOCK-ABSORBERS AND DAMPING SYSTEMS RANGE OF PRODUCTS 7 HOSE CLAMPS AND WIRE SPRINGS RANGE OF PRODUCTS 8 FORMED SPRING IN BAND AND CLAMPING RINGS RANGE OF PRODUCTS 9 CAPS, SOCKETS, QUICK FASTENINGS, PUNCHES AND DIES RANGE OF PRODUCTS 10 AGRICULTURAL SPRINGS, DIE SPRINGS, DIAPHRAGM SPRINGS FOR CLUTCHES, SUSPENSION SPRINGS FOR CARS AND BRAKE SPRINGS FOR LORRIES RANGE OF PRODUCTS 11 TITANIUM SUSPENSION SPRINGS FOR LaFerrari ANNUAL VOLUME OF PRODUCT SOLD 12 Home appliance market Slovakia China Italy Junior dampers 19.000K 24.158K Free Stroke dampers 1.568K Senior dampers 550K Wire -

Summary of CECED Unilateral Industrial Commitments

Summary of CECED Unilateral Industrial Commitments June 2004 Summary of CECED Unilateral Industrial Commitments 2 Voluntary Agreements Index Summary Protocol 1997 9 Voluntary commitment on reducing energy consumption 4 21 of domestic washing machines 1999 9 Voluntary commitment on reducing standing losses 6 29 of domestic electric storage water heaters 9 Voluntary commitment on reducing energy consumption 8 45 of household dishwashers 2000 9 Agreement about the internal verification procedure 9 57 2001 9 Agreement on a common basis for noise declaration for large appliances 10 63 9 Commitment on maximum load declaration 11 65 2002 9 Agreement on a common basis for noise declaration for small appliances 10 63 9 Second voluntary commitment on reducing energy consumption 12 67 of domestic washing machines 9 Voluntary commitment on reducing energy consumption 13 79 of household refrigerators, freezers and their combinations 9 Code of Conduct for A+ / A++ declaration 14 101 2003 9 Energy declaration regarding washing machines 15 103 9 Commitment on maximum load declaration Dishwashers 16 105 National Voluntary Agreements Convention lave vaisselle (Dishwasher agreement), GIFAM, 1996 17 107 Full Protocols Index of the full protocols 19 June 2004 Voluntary Commitment on Reducing energy consumption of domestic washing machines Date of issue: September 24, 1997 Validity Period: from 31 December / 1997 until 31 December / 2001 Signatories Date of signature Signatories Date of signature Miele Nov 1999 Antonio Merloni Nov 1999 Smeg Nov 1999 Arçelik Nov 1999 V-Zug Nov 1999 Brandt Nov 1999 Whirlpool Nov 1999 BSH Nov 1999 Candy Nov 1999 Electrolux Nov 1999 Fagor Nov 1999 Merloni Nov 1999 Commitment: Hard Targets: Step one: participants will stop producing for and importing in the Community Market domestic washing machines which belong to the energy efficiency classes E, F and G after 31.12.1997. -

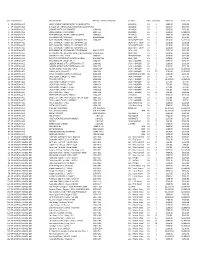

Item Department Nomenclature FSC No / Part No /Serial No Location Unit O Quantity Unit Cost Total Cost 1 SP-MORON-AGE LARGE SCRE

Item Department Nomenclature FSC No / Part No /Serial No Location Unit o Quantity Unit Cost Total Cost 1 SP-MORON-AGE LARGE SCREW THREADING/SET #4/BLUE/METAL 1424/404 EA 1 $300.00 $300.00 2 SP-MORON-AGE AIR JACK 10 T./HYDRAULIC/LARGE/METAL/GREY BOX 1424/404 EA 1 $300.00 $300.00 3 SP-MORON-AGE CABINET/METAL/11 DRAWERS LGM-030 1424/404 EA 1 $525.00 $525.00 4 SP-MORON-AGE LARGE CABINET, TWO DOORS LGM-031 1424/404 EA 4 $500.00 $2,000.00 5 SP-MORON-AGE REFRIGERATOR / WHITE / WRT13CGBW3 LGM-052 1424/410 EA 1 $359.96 $359.96 6 SP-MORON-AGE REFRIGERATOR / KENMORE BA84818486 1424 / 411 EA 1 $359.96 $359.96 7 SP-MORON-AGE BATT CHARGER / TELWIN CO / DYNAMIC 520 LGM-059 1424/ BATT SHOP EA 4 $318.00 $1,272.00 8 SP-MORON-AGE BATT CHARGER / TELWIN CO / DYNAMIC 520 1424 / BATT SHOP EA 1 $318.00 $318.00 9 SP-MORON-AGE BATT CHARGER / TELWIN CO / DYNAMIC 520 1424/ BATT SHOP EA 1 $318.00 $318.00 10 SP-MORON-AGE BATT CHARGER / TELWIN CO / DYNAMIC 520 1424 / BATT SHOP EA 1 $318.00 $318.00 11 SP-MORON-AGE REFRIGERATOR / FRIGADAIRE / FTR18DRHWI BA04219573 1424 / 405 EA 1 $359.96 $359.96 12 SP-MORON-AGE REFRIGERATOR / WESTINGHOUSE / WRT16DGCW2 LA54314337 1424 / 405 EA 1 $359.96 $359.96 13 SP-MORON-AGE HYDRAULIC LIFT / / HL01 LGM-071 1424/HANGAR EA 1 $230.00 $230.00 14 SP-MORON-AGE WHITE INC REFRIGERATOR/WRT13CGBW3 BA62100164 1424 / 405 EA 1 $359.96 $359.96 15 SP-MORON-AGE BEAD BREAKER / SNAP-ON / 1 LGM-081 1424 / HANGER EA 1 $250.99 $250.99 16 SP-MORON-AGE LADDER, MOBILE 6FT / COTTERMAN / 6FT LGM-082 1424 / HANGER EA 2 $101.00 $202.00 17 SP-MORON-AGE LADDER, MOBILE -

Rank Downloads Q3-2017 Active Platforms Q3-2017 1 HP

Rank Brand Downloads Q3-2017 Active platforms q3-2017 Downloads y-o-y 1 HP 303,669,763 2,219 99% 2 Lenovo 177,100,074 1,734 68% 3 Philips 148,066,292 1,507 -24% 4 Apple 103,652,437 829 224% 5 Acer 100,460,511 1,578 58% 6 Samsung 82,907,164 1,997 72% 7 ASUS 82,186,318 1,690 86% 8 DELL 80,294,620 1,473 77% 9 Fujitsu 57,577,946 1,099 94% 10 Hewlett Packard Enterprise 57,079,300 787 -10% 11 Toshiba 49,415,280 1,375 41% 12 Sony 42,057,231 1,354 37% 13 Canon 27,068,023 1,553 17% 14 Panasonic 25,311,684 601 34% 15 Hama 24,236,374 394 213% 15 BTI 23,297,816 178 338% 16 3M 20,262,236 712 722% 17 Microsoft 20,018,316 639 -11% 18 Bosch 20,015,141 516 170% 19 Lexmark 19,125,788 1,067 104% 20 MSI 18,004,192 545 74% 21 IBM 17,845,288 886 39% 22 LG 16,643,142 734 89% 23 Cisco 16,487,896 520 23% 24 Intel 16,425,029 1,289 73% 25 Epson 15,675,105 629 23% 26 Xerox 15,181,934 1,030 86% 27 C2G 14,827,411 568 167% 28 Belkin 14,129,899 440 43% 29 Empire 13,633,971 128 603% 30 AGI 13,208,149 189 345% 31 QNAP 12,507,977 823 207% 32 Siemens 10,992,227 390 183% 33 Adobe 10,947,315 285 -7% 34 APC 10,816,375 1,066 54% 35 StarTech.com 10,333,843 819 102% 36 TomTom 10,253,360 759 47% 37 Brother 10,246,577 1,344 39% 38 MusicSkins 10,246,462 76 231% 39 Wentronic 9,605,067 305 254% 40 Add-On Computer Peripherals (ACP) 9,360,340 140 334% 41 Logitech 8,822,469 1,318 115% 42 AEG 8,805,496 683 -16% 43 Crocfol 8,570,601 162 268% 44 Panduit 8,567,835 163 452% 45 Zebra 8,198,502 433 72% 46 Memory Solution 8,108,528 128 290% 47 Nokia 7,927,162 402 70% 48 Kingston Technology 7,924,495 -

51V Facilities Maintenance and Hardware

GSA Federal Supply Service Facilities Maintenance and Hardware www.gsa.gov/cfmhproducts GSA CMLS Pre-sorted Standard Warehouse 9, Section F Postage & Fees Paid 501 W. Felix Street GSA P.O. Box 6477 Permit No. G-30 Fort Worth, TX 76115-6477 Official Business Penalty for Private Use, $300 Federal Supply Schedule www.gsa.gov January 2005 Multiple Award 51V 5-04-00012 Variable Contract Periods 5040-0012 Cumulative Edition 5 Years from Date of Award October, 2004 Federal Recycling Program Printed on Recycled Paper contentstable of ORDERING INFORMATION . 3 POINTS OF CONTACT. 6 PRODUCT LISTING Hardware Store . 14 Commercial Coatings, Adhesives, Sealants, Fuels and Lubricants . 22 Appliances . 33 To ols . 40 Lawn & Garden Equipment and Cattle Guards . 54 Woodworking and Metalworking . 63 Contractor Team Arrangements and Federal Supply Schedules. 70 Basic Guidelines for Using Contractor Team Arrangements . 71 Suggested Formats . 72 GSA Center for Facilities Maintenance and Hardware GSA Center for Facilities Maintenance and Hardware GSAcenter forf acility m aintenance and h ardware he General Services Administration (GSA) latest information, visit the Schedules E-Library Center for Facility Maintenance and Website at www.gsa.gov/elibrary. GSA awards THardware supports worldwide US competitive contracts to those companies who give us Government requirements for industrial quality hand the same or better discounts than their best tools; office and household appliances; paints and customers, and we pass those discounts on to you. paint brushes; sealants; adhesives; lawn and garden GSA has entered into Government-wide contracts with equipment; woodworking and metalworking equipment commercial firms to provide state-of-the-art, high and machinery; parts; accessories, and services. -

Electrodomesticos Rm

ELECTRODOMESTICOS RM ALCOLEA DE TAJO – 925436637-678543902 COMBI HAIER 188*60 399€ COMBI BOSCH 185*60 485€ HAIER 6KG 1000RPM 249€ BALAY 8KG 1200 RPM 399€ PLACA FAGOR 199€ HORNO PIROLITICO AEG 449€ HORNO BALAY MULTIFUNCION 239€ LAVAVAJILLAS BEKO 285€ LAVAVAJILLAS BOSCH 399€ CAMPANA CATA 90cm 199€ MICROONDAS INTEGRABLE 189€ LAVADORAS BALAY 6KG 1000RPM 299€ BEKO 6KG 1000RPM 269€ INDESIT 6KG 1200RPM 275€ ROMMER 5KG 600RPM 239€ WHIRLPOOL 7KG 1200RPM 319€ ZANUSSI 7KG 1200RPM 299€ SIEMENS 7KG 1000RPM 369€ PANASONIC 7KG 1200RPM 325€ OTSEIN 7KG 1200RPM 319€ HISENSE 7KG 1200RPM 290€ ELECTROLUX 7KG 1200RPM 339€ BOSCH 7KG 1200RPM 375€ AEG 8KG 1200RPM 399€ BEKO 8KG 1000RPM 339€ FAGOR 8KG 1200RPM 379€ CANDY 9KG 1300RPM 425€ LAVAVAJILLAS BALAY A+ 345€ EDESA A+ + 349€ ELECTROLUX A+ 375€ HAIER A+ 299€ ZANUSSI A+ 365€ SIEMENS A++ 430€ CORBERO A+ 290€ OTSEIN A++ 3 BANDEJA 399€ WHIRLPOOL A++ 389€ ZANUSSI A+ 345€ TEKA A+ INOX 375€ WHIRLPOOL A++ INOX 449€ EDESA A+ INOX 375€ BEKO A+ 45cm 319€ CANDY A+ 45cm 325€ FRIGORIFICOS Y COMBIS BEKO 185*60cm NO FROST A+ 449€ CANDY 185*60cm CICLICO 385€ FAGOR 185*60 NO FROST A+ 495€ INDESIT 190*60cm NO FROST A+ 499€ WHIRLPOOL 187*60cm A++ NO FROST 549€ LG 200*60cm NO FROST A++ 699€ BOSCH 200*60cm A++ NO FROST 699€ BEKO 182*91cm 949€ LG 175*90cm 1499€ HISENSE 144*55 259€ EDESA 170*60cm 365€ BEKO 175*60cm 355€ INDESIT 180*70cm 459€ HISENSE 85*55cm 199€ ZANUSSI 85*55cm 219€ INDESIT 150*60 399€ BEKO 171*60cm 429€ CONGELADORES Y ARCONES ROMMER 144*55cm 365€ BEKO 185*60cm 589€ FAGOR 185*60cm 559€ LG 180*60cm 619€ HISENSE 99 LITROS 199€ IGNIS 136 LITROS 249€ ROMMER 255 LITROS 329€ IGNIS 460 LITROS 429€ HORNOS Y PLACAS TEKA INOX 199€ TEKA MULTIF. -

Top 5000 Importers in Fiscal Year 2008

TOP 5000 IMPORTERS IN FISCAL YEAR 2008 NAME ADDR1 ADDR2 CITY STATE ZIP CODE ABERCROMBIE & FITCH TRADING CO 6301 FITCH PATH NEW ALBANY OH 430549269 ADIDAS AMERICA INC 5055 N GREELEY AVE PORTLAND OR 972173524 ADIDAS SALES, INC. ATTN KRISTI BROKAW 5055 N GREELEY AVE PORTLAND OR 972173524 ALDO US INC 2300 EMILE BELANGER MONTREAL CANADA QC H4R3J4 ALPHA GARMENT,INC. 1385 BROADWAY RM 1907 NEW YORK NY 100186001 AMAZON.COM.KYDC, INC. PO BOX 81226 SEATTLE WA 981081300 ANNTAYLOR INC. 7 TIMES SQ RM 1140 NEW YORK NY 100366524 ANVIL KNITWEAR, INC. 146 W COUNTRY CLUB RD HAMER SC 295477289 ARAMARK UNIFORM & CAREER APPAREL 775A TIPTON INDUSTRIAL DRIVE LAWRENCEVILLE GA 300452875 ARIAT INTERNATIONAL INC. 3242 WHIPPLE RD UNION CITY CA 945871217 ASICS AMERICA CORPORATION 29 PARKER STE 100 IRVINE CA 926181667 ASSOCIATED MERCHANDISING CORP. 7000 TARGET PKWY N MAILSTOP NCD-0456 BROOKLYN PARK MN 554454301 ATELIER 4 INC. 3500 47TH AVE LONG ISLAND CITY NY 111012434 BANANA REPUBLIC LLC 2 FOLSOM ST SAN FRANCISCO CA 941051205 BARNEY'S INC. 1201 VALLEY BROOK AVE LYNDHURST NJ 070713509 BCBG MAX AZRIA GROUP INC 2761 FRUITLAND AVE VERNON CA 900583607 BEAUTY AVENUES INC 2 LIMITED PKWY COLUMBUS OH 432301445 BEBE STUDIO, INC. 10345 W OLYMPIC BLVD LOS ANGELES CA 900642524 BED BATH & BEYOND PROCUREMENT CO 110 BI COUNTY BLVD STE 114 FARMINGDALE NY 117353941 BORDERS INC 100 PHOENIX DR ANN ARBOR MI 481082202 BOTTEGA VENETA INC 50 HARTZ WAY SECAUCUS NJ 070942418 BROWN SHOE CO INC 8300 MARYLAND AVE SAINT LOUIS MO 631053693 BURBERRY WHOLESALE LIMITED 3254 N MILL RD STE A VINELAND NJ 083601537 BURLINGTON COAT FACTORY WHSE 1830 ROUTE 130 N BURLINGTON NJ 080163020 BURTON CORPORATION 80 INDUSTRIAL PKY BURLINGTON VT 054015434 BYER CALIFORNIA 66 POTRERO AVE SAN FRANCISCO CA 941034800 C.I. -

Solenoid Valves

Spare parts for: COOKING EQUIPMENT Solenoid valves - Diaphragms - Pressure reducers - Coils This catalogue is automatically generated. Therefore, the sequence of the items might not be always shown at best. Updates will be issued in case of additions and/or amendments. Rel. 2012-03051519 Solenoid valves Suitable for: Suitable for: 3120000 FILTER FOR INLET SOLENOID VALVE ELBI 3120019 INLET PRESSURE REDUCER 5.5 L/min BLACK MEIKO 9506228 3120022 INLET PRESSURE REDUCER 16 L/min BLACK 3120037 OUTLET REDUCER ELBI 0.25 L/min GREEN for ELBI solenoid valve face value +/- 25% MEIKO 9506227 LAINOX R65110410 3120054 COIL SIRAI Z530A 9W 24V 50Hz 14VA 3120138 COIL FOR GAS SOLENOID VALVE 1/2" 230V width 31.5 mm - height 43 mm for BOILING PAN series HD900 depth 42.5 mm RANCILIO ZANUSSI 005548 3120170 SOLENOID VALVE 101 ø 3/4"M 1/2"F 24V 3120000 FILTER FOR INLET SOLENOID VALVE ELBI normally closed - brass body 24V 50Hz - max 120°C HOONVED H120141 MEIKO 9506228 3120026 COIL ELBI 24V ac for solenoid valves 101-102-254-261 old type COMENDA 630967 HOONVED H630967 pg. 2 Solenoid valves Suitable for: Suitable for: 3120202 OUTLET REDUCER ELBI 0.35 L/min YELLOW 3120204 OUTLET REDUCER ELBI 5.5 L/min BROWN for ELBI solenoid valve for ELBI solenoid valve face value +/- 25% face value +/- 25% ZANUSSI 0W2908 3120293 GAS SOLENOID VALVE ø 3/8" 5W 110/120V for FRYER series SPG-SPGR GARLAND G02965-1 3120365 SOLENOID VALVE ø 3/8" FF 230V 1120820 COIL ODE BDA08223DS 220/230V 50Hz 8W for steam - normally closed width 30 mm - height 39 mm max temperature 140°C depth 42 mm max.