Grace at the End of Life: Rethinking Ordinary and Extraordinary Means in a Global Context Conor Kelly

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Sponsor Opportunities

World Congress of Families IX SPONSOR OPPORTUNITIES Salt Lake City Oct. 27-30, 2015 Hosted by Amsterdam, 2009 Warsaw,, 2007 Prague,PPragguee, 1191997977 Geneva,Geneva, 11999 Salt Lake City, 2015 Madrid, 2012 Mexico City, 2004 Sydney, 2013 Introducing the World Congress of Families The premier international gathering of leaders, scholars, advocates and citizens uniting in support of the natural family as the fundamental unit of society. Since 1997, the World Congress of Families has met all over the globe to advance pro-family scholarship and policy in a celebration of faith, family and freedom. Coming to Salt Lake City in October 2015, the ninth World Congress of Families will attract thousands of pro- family attendees, scholars and policymakers from across the United States and more than 80 countries, as well as journalists from major media outlets. As the event organizer, Sutherland Institute invites you to join us in acclaiming the natural family as the fundamental unit of society. Please review the various advertising and sponsorship opportunities available to place your company on the world stage during this high-profile event. In the following pages, you will see a variety of sponsorship options. Please note that all sponsorship packages can be customized to fit your needs. Our goal is to help you achieve your desired outcomes as a supporter and partner of the ninth World Congress of Families. 2 Notable past speakers, supporters and attendees Helan Alvare Law Professor, George Mason University; formerly in the Office of General Counsel for the National Conference of Catholic Bishops The Hon. Kevin Andrews Australia Minister for Social Services Cardinal Ennio Antonelli President of the Pontifical Council for Family (Holy See), Roman Catholic Church Gary Becker Nobel Laureate in Economics Cardinal Raymond Leo Burke Cardinal Prefect of the Supreme Tribunal of the Apostolic Signatura Sheri Dew CEO of Deseret Book Company Patrick Fagan, Ph.D. -

Studies of Religion Environmental Ethics Unit 2015

1 Studies of Religion Environmental Ethics Unit, Christian NSW Catholic Sustainable Schools Project November 2015 Stage 6 Studies of Religion Environmental Ethics Unit, Christian Catholic Sustainable developed and supported by Schools Network NSW 2 Introduction To assist teachers undertaking the Environmental Ethics unit within the Stage 6 Studies of Religion. This Unit has been developed with assistance from the Office of Environment & Heritage (OEH), and the Association of the Studies of Religion (ASR). A small writing team was formed. Writing team: Catholic Sustainable Schools Network – Sue Martin (St Ignatius’ College, Riverview) & Anne Lanyon (Columban Mission Institute) New South Wales Office of Environment & Heritage – Mark Caddey Association of the Studies of Religion –Louise Zavone Catholic Mission - Beth Riolo Catholic Education Archdiocese of Canberra & Goulburn - Kim-Maree Goodwin Loreto College Normanhurst - Libby Parker Marist Sisters College Woolwich - Andrew Dumas Our Lady of Mercy College Parramatta - Natalie White St Patrick’s Campbelltown Campbelltown - Maria Boulatsakos Project Background This resource provides up-to-date material for students and teachers wanting to engage with the Environmental Ethics component of the Studies of Religion Course. The nature of Christian Environmental Ethics is evolving in the context of the signs of the times. With the publication by Pope Francis on 24th May, 2015 of the first Encyclical on the environment, “Laudato Si”, official Catholic Teaching on Environmental Ethics is taking a new direction. Catholic environmental teaching is moving from an anthropocentric position to a perspective of universal communion. As with Catholicism, Orthodoxy and Protestant variants are continuing to develop and provide guidance to their adherence in the forms of teachings and official documents. -

Reflections on the Future of Social Justice

The Catholic University of America, Columbus School of Law CUA Law Scholarship Repository Scholarly Articles and Other Contributions Faculty Scholarship 2000 Reflections on the uturF e of Social Justice Lucia A. Silecchia The Catholic University of America, Columbus School of Law Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.law.edu/scholar Part of the Law and Society Commons, and the Religious Thought, Theology and Philosophy of Religion Commons Recommended Citation Lucia A. Silecchia, Reflections on the uturF e of Social Justice, 23 SEATTLE U. L. REV. 1121 (2000). This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Faculty Scholarship at CUA Law Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Scholarly Articles and Other Contributions by an authorized administrator of CUA Law Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Reflections on the Future of Social Justice This paper contains remarks made on October 18, 1999 as part of the Dedication Celebrationfor the Seattle University School of Law. Lucia A. Silecchia* Good afternoon. Let me begin by offering my warmest congrat- ulations and heartiest best wishes to the students, faculty, administra- tion, and staff of Seattle University's School of Law. This week of celebration is the culmination of years of careful planning, endless meetings, and for some, I am sure, many nights "sleepless in Seattle" as your plans for this new building grew into the reality that you cele- brate and dedicate this week. I wish you many years of success in your new home, and I hope that here the traditions of your past and your hopes for the future find harmony and fulfillment. -

In Pastoral, Indiana Bishops Urge Welcoming Immigrants Chosen From

Poet laureate? At 90, Dorothy Colgan stays busy writing poetry, page 28. Serving the ChurchCriterion in Central and Southern Indiana Since 1960 CriterionOnline.com January 12, 2007 Vol. XLVII, No. 13 75¢ In pastoral, Indiana bishops urge welcoming immigrants The Criterion staff report Gettelfinger. XVI’s first encyclical, Deus Caritas (“God and responsibility to provide secure bor- Typically, statements from the bishops is Love”), saying “there is an intimate and ders for the protection of our people and The Indiana Catholic bishops call the are done though the Indiana Catholic unbreakable connection between love of to guard against those who would do faithful “to welcome others as Christ him- Conference, the Church’s official public God and love of neighbor. In loving our harm,” but the bishops “reject positions or self” in a pastoral let- policy voice. However, the pastoral letter neighbor, we meet the person of Christ.” policies that are anti-immigrant, nativist, ter on the treatment of is a unique move by the bishops giving The pastoral defines a neighbor “not ethnocentric or racist. Such narrow and immigrants issued on the statement a distinctive teaching simply as someone who is familiar and destructive views are profoundly anti- Jan. 12. authority which carries more significance close at hand, [nor] someone who shares Catholic and anti-American.” Titled “I Was a and weight—that of shepherds addressing my ethnic, social or racial characteristics.” They call for balance between “the Stranger and You the faithful. Rather, as the Gospels define neighbor, right of a sovereign state to control its Welcomed Me: “We Catholic bishops of Indiana “Our neighbor is anyone who is in need— borders, and “the right of human persons Meeting Christ in New recommit ourselves and our dioceses to including to migrate Neighbors,” the pas- welcoming others as Christ himself,” the those who are so that they toral is the first of its pastoral says. -

Malloy Hall Honors Family Legacy

S F A Hi-Lites O Fall 2001 I Y N Why the Church? T T I ...........................Page 3 T S Music to His Ears H R ...........................Page 3 C O E R O E T S IS C M V R A H Distinguish Yourself M US IN C I A N ...........................Page 4 S U ¥ UST Salutes the Parisis ...........................Page 6 A Publication of the University of St. Thomas MALLOY HALL HONORS FAMILY LEGACY The Malloy family gift to UST is in memory of Eugene Malloy, who served on the Board for many years, and his wife Felice, both major UST benefactors since 1973. The Real Malloy Dennis Malloy stepped forward as the first living board member in UST history to give a $1 million gift to the University of St. Thomas. As a result, UST will call its new humanities and education building the Eugene and Felice Malloy Hall. See “Malloy Hall,” Page 7. Pope’s Human Rights Observer Will Lecture at UST This year’s Catholic Intellectual Tradition Lecture Series speaker, Archbishop Renato Martino, has for almost four decades occupied Maureen and Jim Hackett: a front-row seat in the worldwide human rights arena.” See “Catholic,” Page 5. New Philanthropy Hall of Famers Working for UST Catholic Intellectual Tradition Lecture Series. Maureen and James T. Hackett, UST Mardi Gras gala co-chairs, have also agreed to serve on the 8 p.m. Tuesday • Sept. 25 • Jones Hall • 3910 Yoakum Honorary Committee of the University of St. Thomas Capital Campaign. Make plans now to attend the Mardi Gras gala on Feb. -

Catholicism and European Politics: Introducing Contemporary Dynamics

religions Editorial Catholicism and European Politics: Introducing Contemporary Dynamics Michael Daniel Driessen Department of Political Science and International Affairs, John Cabot University, 00165 Rome, Italy; [email protected] 1. Introduction Recent research on political Catholicism in Europe has sought to theorize the ways in which Catholic politics, including Catholic political parties, political ideals, and political entrepreneurs, have survived and navigated in a post-secular political environment. Many of these studies have articulated the complex ways in which Catholicism has adjusted and transformed in late modernity, as both an institution and a living tradition, in ways which have opened up unexpected avenues for its continuing influence on political practices and ideas, rather than disappearing from the political landscape altogether, as much Citation: Driessen, Michael Daniel. previous research on religion and modernization had expected. Among other things, this 2021. Catholicism and European new line of research has re-evaluated the original and persistent influence of Catholicism Politics: Introducing Contemporary on the European Union, contemporary European politics and European Human Rights Dynamics. Religions 12: 271. https:// discourses. At the same time, new political and religious dynamics have emerged over doi.org/10.3390/rel12040271 the last five years in Europe that have further challenged this developing understanding of contemporary Catholicism’s relationship to politics in Europe. This includes the papal Received: 26 March 2021 election of Pope Francis, the immigration “crisis”, and, especially, the rise of populism and Accepted: 6 April 2021 new European nationalists, such as Viktor Orbán, Jaroslaw Kaczynski and Matteo Salvini, Published: 13 April 2021 who have publicly claimed the mantles of Christian Democracy and Catholic nationalism while simultaneously refashioning those cloaks for new ends. -

Provincial Newsletter Boletín Provincial July and August 2008

Provincial Newsletter Boletín Provincial Province of Saint John the Baptist 546 North East Avenue Oak Park, IL 60302-2207 Phone 708/386-4430 Fax 708/386-4457 Email: [email protected] Contents – Indice Page Around the Province 2 Noticias de la Provincia 4 Birthdays, Anniversaries and In Memoriam 6 Young Religious Meeting 7 Movimiento Laico Scalabriniano 8 Vocation Statistics 10 Casa del Migrante – Nuevo Laredo 11 Cardinals see Immigration 16 Renewing Hope, Seeking Justice on Immigration 19 Guatemala: Mensaje para el Día del Migrante 25 Welcome the Stranger 28 Employers Fight Tough Measures on Immigration 30 July and August 2008 Issue 4 1 Around the Province First Profession The four novices of Noviciado Scalabrini, Purépero, were admitted to the First Profession: Juan Martín Cervantes Álvarez, Marcos Manuel López Bustamante, Marco Antonio Ortíz Ramírez and José Grimaldo Monjaraz. The celebration will take place on November 28, 2008, in Purépero. Perpetual Profession Juan Luis Carbajal Tejeda, a religious student of the Scalabrini House of Theology, Chicago, was admitted to the Perpetual Profession. The celebration will take place on November 4, 2008, in Chicago. Renewal of Vows The following religious students of the Scalabrini House of Theology were approved to the renewal of vows on November 4, 2008: Jaime Aguila, Alejandro Conde, Óscar Cuapio, Francesco D’Agostino, Antonius Faot, José Rodrigo Gris, Frandry Tamar and Fransiskus Yangminta. Priesthood Ordinations Brutus Brunel will be ordained on September 20, 2008 in Sainte Thérése de l’Enfant Jésus in Port-au-Prince, Haiti, by Most Rev. Simon-Pierre Saint-Hillien, CSC, Coadjutor Bishop of Port-au-Prince. -

Climate Change and the Holy See the Development of Climate Policy Within the Holy See Between 1992 and 2015

Climate Change and the Holy See The development of climate policy within the Holy See between 1992 and 2015 Master thesis MSc International Public Management and Policy By Wietse Wigboldus (418899) 1st Reader: dr. M. Onderco 2nd Reader: dr. K.H. Stapelbroek Word count: 24668 Date: 24-07-2016 2 Table of Contents Summary ....................................................................................................................................................... 5 Abbreviations ................................................................................................................................................ 6 Chapter 1 – Introduction ............................................................................................................................... 7 Introduction to topic ................................................................................................................................. 7 Research question and aim of thesis ......................................................................................................... 8 Relevance .................................................................................................................................................. 9 Chapter 2 – Literature Review ..................................................................................................................... 10 Introduction ............................................................................................................................................. 10 Foreign -

Tip of the Iceberg: Religious Extremist Funders Against Human Rights for Sexuality and Reproductive Health in Europe 2009 - 2018

TIP OF THE ICEBERG Religious Extremist Funders against Human Rights for Sexuality and Reproductive Health in Europe 2009 - 2018 TIP OF THE ICEBERG Religious Extremist Funders against Human Rights for Sexuality and Reproductive Health in Europe 2009 – 2018 ISBN: 978 2 93102920 6 Tip of the Iceberg: Religious Extremist Funders against Human Rights for Sexuality and Reproductive Health in Europe 2009 - 2018 Written by Neil Datta, Secretary of the European Parliamentary Forum for Sexual and Reproductive Rights. Brussels, June 2021 Copyright © EPF 2021 All Rights Reserved. The contents of this document cannot be reproduced without prior permission of the author. EPF is a network of members of parliaments from across Europe who are committed to protecting the sexual and reproductive health of the world’s most vulnerable people, both at home and overseas. We believe that women should always have the right to decide upon the number of children they wish to have, and should never be denied the education or other means to achieve this that they are entitled to. Find out more on epfweb.org and by following @EPF_SRR on Twitter. 2 TIP OF THE ICEBERG Religious Extremist Funders against Human Rights for Sexuality and Reproductive Health in Europe 2009 – 2018 Tip of the Iceberg is the first attempt understand the anti-gender mobilisation in Europe through the perspective of their funding base. This report assembles financial data covering a ten year period of over 50 anti-gender actors operating in Europe. It then takes a deeper look at how religious extremists generate this funding to roll back human rights in sexuality and reproduction. -

How Many Divisions Has He G

University of Bath PHD “How many divisions has he got?” The Holy See’s soft power on the US Wars in Iraq, 1991 & 2003 Cahill, Luke Award date: 2019 Awarding institution: University of Bath Link to publication Alternative formats If you require this document in an alternative format, please contact: [email protected] General rights Copyright and moral rights for the publications made accessible in the public portal are retained by the authors and/or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. • Users may download and print one copy of any publication from the public portal for the purpose of private study or research. • You may not further distribute the material or use it for any profit-making activity or commercial gain • You may freely distribute the URL identifying the publication in the public portal ? Take down policy If you believe that this document breaches copyright please contact us providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. Download date: 26. Sep. 2021 Citation for published version: Cahill, L 2019, '“How many divisions has he got?” The Holy See’s soft power on the US Wars in Iraq, 1991 & 2003', Ph.D., University of Bath. Publication date: 2019 Link to publication University of Bath General rights Copyright and moral rights for the publications made accessible in the public portal are retained by the authors and/or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. -

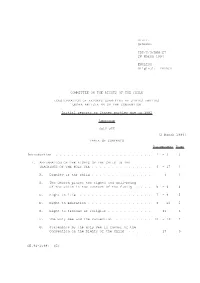

Distr. GENERAL CRC/C/3/Add.27 28 March 1994 ENGLISH Original

Distr. GENERAL CRC/C/3/Add.27 28 March 1994 ENGLISH Original: FRENCH COMMITTEE ON THE RIGHTS OF THE CHILD CONSIDERATION OF REPORTS SUBMITTED BY STATES PARTIES UNDER ARTICLE 44 OF THE CONVENTION Initial reports of States parties due in 1992 Addendum HOLY SEE [2 March 1994] TABLE OF CONTENTS Paragraphs Page Introduction ........................ 1 -3 3 I. AFFIRMATION OF THE RIGHTS OF THE CHILD IN THE TEACHINGS OF THE HOLY SEE............... 4 -17 3 A. Dignity of the child............... 4 3 B. The Church places the rights and well-being of the child in the context of the family .... 5 -6 4 C. Right to life .................. 7 -8 5 D. Right to education................ 9 -10 5 E. Right to freedom of religion........... 11 6 F. The Holy See and the Convention ......... 12-16 7 G. Statements by the Holy See in favour of the Convention on the Rights of the Child ...... 17 9 GE.94-15987 (E) CRC/C/3/Add.27 page 2 CONTENTS (continued) Paragraphs Page II. ACTIVITY OF THE HOLY SEE ON BEHALF OF CHILDREN .... 18-43 10 A. Holy See and Church structures dealing with children..................... 19-23 10 B. Implementation of the Convention......... 24-43 12 III. ACTIVITIES OF THE PONTIFICAL COUNCIL FOR THE FAMILY FOR THE PROTECTION OF THE RIGHTS OF THE CHILD....... 44-59 15 A. Meeting on the rights of the child (Rome, 18-20 June 1992) ............. 45-46 15 B. International meeting on the sexual exploitation of children through prostitution and pornography (Bangkok, 9-11 September 1992).......... 47-50 16 C. -

'Gaddafi Should Have Been Put on Trial'

THE CATHOLIC HERALD NOVEMBER 4 2011 7 Features Editor: Ed West INTERVIEW Tel: 020 7448 3601 Fax: 020 7256 9728 Email: [email protected] ‘Gaddafi should have been put on trial’ Ed West meets Cardinal Renato Martino, the outspoken former Vatican official who still has a seat in the front row of history hen I meet for the release of Youcef Cardinal Nadarkhani, the Iranian Renato Christian pastor sentenced to Raffaele death for apostasy (even WMartino, president emeritus though he has never claimed of the Pontifical Council to be a Muslim), a matter for Justice and Peace, he which many feel the Catholic has just been in Westmin- Church has been silent over? ster Cathedral for the royal “Yes,” he says, and then investiture of the Order of smiles. “I had many of these St George’s grand master, cases during my 40 years as a Prince Carlo of Bourbon diplomat of the Holy See and Two Sicilies, Duke of eight years of the Pontifical Castro, and the sub-prior Council for Justice and Archbishop George Stack Peace. of Cardiff. The guest “I hope to have the time to speaker at the royal gala write some of my memories, dinner later on was Arch- of things that I have seen bishop Vincent Nichols of personally, because I think Westminster, to which that [an understanding of] Mary McAleese of Ireland some events in the world sent formal greetings. It would be helped if every- was a rather big event. body knows what happened. The order, or to give it is Like this particular case: its full title, the Sacred Mili- everybody agrees.