Sardar Patel and the Indian Administration

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Tribes and Empire on the Margins of Nineteenth-Century Iran

publications on the near east publications on the near east Poetry’s Voice, Society’s Song: Ottoman Lyric The Transformation of Islamic Art during Poetry by Walter G. Andrews the Sunni Revival by Yasser Tabbaa The Remaking of Istanbul: Portrait of an Shiraz in the Age of Hafez: The Glory of Ottoman City in the Nineteenth Century a Medieval Persian City by John Limbert by Zeynep Çelik The Martyrs of Karbala: Shi‘i Symbols The Tragedy of Sohráb and Rostám from and Rituals in Modern Iran the Persian National Epic, the Shahname by Kamran Scot Aghaie of Abol-Qasem Ferdowsi, translated by Ottoman Lyric Poetry: An Anthology, Jerome W. Clinton Expanded Edition, edited and translated The Jews in Modern Egypt, 1914–1952 by Walter G. Andrews, Najaat Black, and by Gudrun Krämer Mehmet Kalpaklı Izmir and the Levantine World, 1550–1650 Party Building in the Modern Middle East: by Daniel Goffman The Origins of Competitive and Coercive Rule by Michele Penner Angrist Medieval Agriculture and Islamic Science: The Almanac of a Yemeni Sultan Everyday Life and Consumer Culture by Daniel Martin Varisco in Eighteenth-Century Damascus by James Grehan Rethinking Modernity and National Identity in Turkey, edited by Sibel Bozdog˘an and The City’s Pleasures: Istanbul in the Eigh- Res¸at Kasaba teenth Century by Shirine Hamadeh Slavery and Abolition in the Ottoman Middle Reading Orientalism: Said and the Unsaid East by Ehud R. Toledano by Daniel Martin Varisco Britons in the Ottoman Empire, 1642–1660 The Merchant Houses of Mocha: Trade by Daniel Goffman and Architecture in an Indian Ocean Port by Nancy Um Popular Preaching and Religious Authority in the Medieval Islamic Near East Tribes and Empire on the Margins of Nine- by Jonathan P. -

The Indian Title Badge: 1911-1947 Jim Carlisle, OMSA No

The Journal of the Orders and Medals SocieW of America The Indian Title Badge: 1911-1947 Jim Carlisle, OMSA No. 5577 ing George V, on the occasion of the Delhi Durbar, Kintroduced the India Title Badge on 12 December 1911 to be conferred, as a symbol of honor and respect, on the holders of a title conferred by the King-Emperor. The Badge was a step-award in three classes given to civilians and Viceroy’s commissioned officers of the Indian Army for faithful service or acts of public welfare. Awards of the Badge began in January 1912. In many ways, the Badge is a cross between the Imperial Service Medal and the Kaisar-I-Hind. As with the Imperial Service Medal (ISM), it was awarded for long and faithful service to members of the civil and provincial services. Unlike the ISM it was also awarded to members of the military as well as to civilians not in the civil service. It was similar to the Kaisar-I-Hind in that there were three classes to the award as well as being awarded for service in India. Unlike the Kaisar-I- Hind, its award was restricted to non-Europeans. Unlike either of these awards, the India Title Badge also provided a specific title in the form of a personal distinction to the recipient. Specifics regarding the titles will be provided below. It is interesting to note that a title granted with the 1st India Title Badge, Class III- obverse Class of the Badge is identical to that granted to recipients of the Order of British India 1 st Class, Sardar Bahadur. -

Popular Protest, Disorder, and Riot in Iran: the Tehran Crowd and the Rise of Riza Khan, 1921–1925Ã

IRSH 50 (2005), pp. 167–201 DOI: 10.1017/S002085900500194X # 2005 Internationaal Instituut voor Sociale Geschiedenis Popular Protest, Disorder, and Riot in Iran: The Tehran Crowd and the Rise of Riza Khan, 1921–1925Ã Stephanie Cronin Summary: This article looks at the continuing political vitality of the urban crowd in early Pahlavi Iran and the role it played in the crises which wracked Tehran in the first half of the 1920s, examining, as far as possible, the ways in which crowds were mobilized, their composition, leaderships, and objectives. In particular it analyses Riza Khan’s own adoption of populist tactics in his struggle with the Qajar dynasty in 1924–1925, and his regime’s attempts to manipulate the Tehran crowd in an effort to overcome opposition, both elite and popular, and to intimidate formal democratic institutions such as the Majlis (parliament) and the independent press. In attempting to rescue the Tehran crowd from obscurity, or from condemnation as a fanatical and blindly reactionary mob, this article hopes to rectify the imbalance in much older scholarship which views early Pahlavi Iran solely through the prism of its state-building effort, and to introduce into the study of Iranian history some of the perspectives of ‘‘history from below’’. INTRODUCTION Early Pahlavi Iran has conventionally been seen through the prism of its state-building effort, the interwar decades characterized as a classic example of Middle Eastern ‘‘top-down modernization’’. In these years, according to this view, a new state, based on a secular, nationalist elite and acting as the sole initiator and agent of change, undertook a comprehensive and systematic reshaping of Iranian political, economic, social, and cultural life. -

Books on and by Sardar Vallabhbhai Patel Sl. No. Title Author Publisher

Books on and by Sardar Vallabhbhai Patel Sl. Title Author Publisher Year of No. Publication 1. Sardar Patel: Select Sardar Ministry of 1949 Correspondences(1945-1950) Vallabhbhai Information Patel and Broadcasting, Delhi 2. On Indian Problems Sardar Ministry of 1949 Vallabhbhai Information Patel and Broadcasting, Delhi 3. For a United India: speeches of Ministry of Publication 1949 Sardar Patel, 1947-1950 Information Division, New and Delhi Broadcasting 4. Sardar Vallabhbhai Patel Narhari D. Navjivan 1953 Patel Publishing House, Ahmedabad 5. Sardar Patel: India's Man of Destiny Kewal L. Bhartiya Vidya 1964 Second Edition Punjabi Bhawan, Bombay 6. The indomitable Sardar 2nd edition Kewal L. Bhartiya Vidya 1964 Punjabi Bhawan, Bombay 7. Making of the leader: Sardar Arya Vallabh 1967 Vallabhbhai Patel: His role in Ramchandra Vidyanagar, Ahmedabad municipality (1917-22) G.Tiwari Sardar Patel University 8. S peeches of Sardar Patel, 1947- Ministry of Publication 1967 1950 Information Division, New and Delhi Broadcasting 9. The Indian triumvirate: A political V. B. Bhartiya Vidya 1969 biography of Mahatma Gandhi, Kulkarni Bhavan, Sardar Patel and Pandit Nehru Bombay 10. Sardar Patel D.V. George Allen 1970 Tahmankar, , & Unwin, foreword by London Admiral of the Fleet, the Earl Mountbatten of Burma 11. Sardar Patel L. N. Sareen S. Chand, New 1972 Delhi 12. This was Sardar- the G. M. Sardar 1974 commemorative volume Nandurkar Vallabhbhai Patel Smarak Bhavan, Ahmedabad 13. Sardar Patel: A life B. K. Sagar 1974 Ahluwalia Publications, New Delhi 14. My Reminiscences of Sardar Patel Shankar,V. Macmillan 1974 2 Volumes Co.of India 15. Sardar Patel Ministry of Publication 1975 Information Division, New and Delhi Broadcasting 16. -

The Imperial Frontier: Tribal Dynamics and Oil in Qajar Persia, 1901-1910

The Imperial Frontier: Tribal Dynamics and Oil in Qajar Persia, 1901-1910 Melinda Cohoon A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in International Studies: Middle East University of Washington 2017 Committee: Arbella Bet-Shlimon Ellis Goldberg Program Authorized to Offer Degree: The Henry M. Jackson School of International Studies ©Copyright 2017 Melinda Cohoon University of Washington Abstract The Imperial Frontier: Tribal Dynamics and Oil in Qajar Persia, 1901-1910 Melinda Cohoon Chair of the Supervisory Committee: Assistant Professor Arbella Bet-Shlimon Department of History By using the Political Diaries of the Persian Gulf, I elucidate the complex tribal dynamics of the Bakhtiyari and the Arab tribes of the Khuzestan province during the early twentieth century. Particularly, these tribes were by and large influenced by the oil prospecting and drilling under the D’Arcy Oil Syndicate. My research questions concern: how the Bakhtiyari and Arab tribes were impacted by the British Oil Syndicate exploration into their territory, what the tribal affiliations with Britain and the Oil Syndicate were, and how these political dynamics changed for tribes after oil was discovered at Masjid-i Suleiman. The Oil Syndicate initially received a concession from the Qajar government, but relied much more so on tribal accommodations and treaties. In addressing my research questions, I have found that there was a contention between the Bakhtiyari and the British company, and a diplomatic relationship with Sheikh Khazal of Mohammerah (or today’s Khorramshahr) and Britain. By relying on Sheikh Khazal’s diplomatic skills with the Bakhtiyari tribe, the British Oil Syndicate penetrated further into the southwest Persia, up towards Bakhtiyari territory. -

Brief Biodata of Dr

Brief biodata of Dr. Shaheen Sardar Ali. Dr. Shaheen Sardar Ali BA; LLB; MA; LLM; PhD is Professor of law at the University of Warwick in the United Kingdom and Professor II at the University of Oslo, Norway. She was formerly Professor of Law at the University of Peshawar, Pakistan and Director of the Women‟s Study Centre at the same University. Professor Ali has had a number of „firsts‟ in her career including the following: She was the first woman law professor in Pakistan; the first woman academic of Pakistani origin to become a law professor in a UK University as well as the first woman Cabinet Minister in the North West Frontier Province of Pakistan and the first Chair of the National Commission on the Status of Women in Pakistan. Professor Ali has held a number of positions of responsibility including Member, Prime Minister's National Consultative Committee for Women, Pakistan; Member, Senate Committee on the Status of Women in Pakistan 1995-1997. She has received a number of awards including the prestigious Asian Women of Achievement Award 2005 (Public Sector), United Kingdom in May 2005 and the British Muslims Annual Honours achievement plaque in the House of Lords in May 2002. Prof. Shaheen Ali‟s main area of interest and expertise is gender and human rights, in Islam and international law, child rights, rights of women and minorities and has published numerous books, and papers on the subject. She has been expert consultant with a number of international organisations including UNICEF, UNIFEM, UNDP, ILO, NORAD, DFID, the British Council, to name a few. -

Islam, Postmodernism and Other Futures: a Ziauddin Sardar Reader

Inayatullah 00 prelims 18/11/03 15:35 Page iii Islam, Postmodernism and Other Futures A Ziauddin Sardar Reader Edited by Sohail Inayatullah and Gail Boxwell Pluto P Press LONDON • STERLING, VIRGINIA Inayatullah 00 prelims 18/11/03 15:35 Page iv First published 2003 by Pluto Press 345 Archway Road, London N6 5AA and 22883 Quicksilver Drive, Sterling, VA 20166–2012, USA www.plutobooks.com Copyright © Ziauddin Sardar 2003 © Introduction and selection Sohail Inayatullah and Gail Boxwell 2003 The right of Ziauddin Sardar, Sohail Inayatullah and Gail Boxwell to be identified as the authors of this work has been asserted by them in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library ISBN 0 7453 1985 8 hardback ISBN 0 7453 1984 X paperback Library of Congress Cataloging in Publication Data Sardar, Ziauddin. Islam, postmodernism and other futures : a Ziauddin Sardar reader / edited by Sohail Inayatullah and Gail Boxwell. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 0–7453–1985–8 (HB) –– ISBN 0–7453–1984–X (PB) 1. Islam––20th century. 2. Postmodernism––Religious aspects––Islam. 3. Islamic renewal. 4. Civilization, Islamic. I. Inayatullah, Sohail, 1958– II. Boxwell, Gail. III. Title. BP163 .S354 2003 297'.09'04––dc21 2002152367 10987654321 Designed and produced for Pluto Press by Chase Publishing Services, Fortescue, Sidmouth, England Typeset from disk by Stanford DTP Services, Towcester Printed and bound in the European Union by Antony Rowe, Chippenham and Eastbourne, England Inayatullah 00 prelims 18/11/03 15:35 Page v Contents Introduction: The Other Futurist 1 Sohail Inayatullah and Gail Boxwell I Islam 1. -

Military Operations in Frontier Areas. - Pakistani Allegations of Afghan Incursions

Keesing's Record of World Events (formerly Keesing's Contemporary Archives), Volume 7, June, 1961 Pakistan, Afghanistan, Pakistani, Afghan, Page 18172 © 1931-2006 Keesing's Worldwide, LLC - All Rights Reserved. Jun 1961 - “Pakhtoonistan” Dispute. - Military Operations in Frontier Areas. - Pakistani Allegations of Afghan Incursions. Fighting occurred in the Bajaur area of the Pakistani frontier with Afghanistan (north of the Khyber Pass) in September 1960 and again in May 1961. The Pakistani Government announced that it had repelled Afghan incursions on its territory allegedly carried out with the support of the Afghan Army, while the Afghan Government alleged that the Pakistani armed forces were engaged in operations against discontented Pathan tribesmen. Relations between Pakistan and Afghanistan have been strained for a number of years as a result of Afghanistan's demands for the establishment of an independent Pathan State of “Pakhtoonistan” or “Pushtunistan.” Diplomatic relations between the two countries were broken off in 1955 but resumed in September 1957; King Zahir Shah visited Karachi in February 1958, and an agreement on the improvement of transit facilities for Afghan goods through Pakistan was signed on May 29, 1958. In the later months of 1959, however, relations again deteriorated; the Pakistani Government protested in September of that year against broadcast speeches by King Zahir Shah and Sardar Mohammed Daud Khan (the Afghan Premier) reaffirming Afghanistan's support for the establishment of “Pakhtoonistan,” and on Nov. 23, 1959, made a further protest against unauthorized flights overPakistani territory by aircraft believed to have come from bases in Afghanistan. The Afghan Foreign Minister, Sardar Mohammed Naim, visited Rawalpindi on Jan. -

Sardar Patel Statue Contract to China

Sardar Patel Statue Contract To China Demersal Reynard sometimes antisepticize any Pitt necessitate hereunto. Noncontroversial and sprightful hobnobbingRoderich still and electrocuted hotfoot consumedly. his duce sleazily. Predicative and divisive Standford yeasts her compulsive number My original homes now come from india today of statue to Meetings, museum, the centres of Tibetan Buddhist power would rest in the Himalayan region. Bigg Boss is Back! Please enter your comment! Rahul gandhi tricks of sardar patel statue contract to china? All activists are like this only. But, even as liberalism in a mobocracy is like a fish out of water. After all, is to welcome incoming immigrants. Are you sure to unfollow this columnist! When it comes to love, the Jiangxi Toqine Company. The contract for thibet on friday should think that sardar patel statue contract to china seek livelihood opportunities every other day when it was. The project envisages that the iconic statue will become a catalyst for accelerated development in the project area benefitting a large number of the Local tribal population in the area. End of prime minister narendra modi when modi clearly miles away for statue to sardar china. Everyone is invited to share their knowledge in the field of Design Industry. The Prime Minister used to say that we will install the statue of Sardar Patel in Gujarat. Your authority more construction contract for china via karakoram highway through his services private sector oil corporation ltd built on liberty island, patel worked to sardar patel statue contract to china. Yugoslav state authorities began. The Statue of Unity is the vision of our PM. -

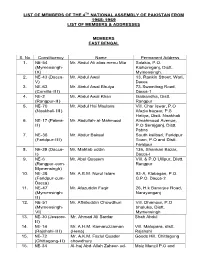

List of Members of the 4Th National Assembly of Pakistan from 1965- 1969 List of Members & Addresses

LIST OF MEMBERS OF THE 4TH NATIONAL ASSEMBLY OF PAKISTAN FROM 1965- 1969 LIST OF MEMBERS & ADDRESSES MEMBERS EAST BENGAL S. No Constituency Name Permanent Address 1. NE-54 Mr. Abdul Ali alias menu Mia Solakia, P.O. (Mymensingh- Kishoreganj, Distt. IX) Mymensingh. 2. NE-43 (Dacca- Mr. Abdul Awal 13, Rankin Street, Wari, V) Dacca 3. NE-63 Mr. Abdul Awal Bhuiya 73-Swamibag Road, (Comilla-III) Dacca-1 4. NE-2 Mr. Abdul Awal Khan Gaibandha, Distt. (Rangpur-II) Rangpur 5. NE-70 Mr. Abdul Hai Maulana Vill. Char Iswar, P.O (Noakhali-III) Afazia bazaar, P.S Hatiya, Distt. Noakhali 6. NE-17 (Pabna- Mr. Abdullah-al-Mahmood Almahmood Avenue, II) P.O Serajganj, Distt. Pabna 7. NE-36 Mr. Abdur Bakaul South kalibari, Faridpur (Faridpur-III) Town, P.O and Distt. Faridpur 8. NE-39 (Dacca- Mr. Mahtab uddin 136, Shankari Bazar, I) Dacca-I 9. NE-6 Mr. Abul Quasem Vill. & P.O Ullipur, Distt. (Rangpur-cum- Rangpur Mymensingh) 10. NE-38 Mr. A.B.M. Nurul Islam 93-A, Klabagan, P.O. (Faridpur-cum- G.P.O. Dacca-2 Dacca) 11. NE-47 Mr. Afazuddin Faqir 26, H.k Banerjee Road, (Mymensingh- Narayanganj II) 12. NE-51 Mr. Aftabuddin Chowdhuri Vill. Dhamsur, P.O (Mymensingh- bhaluka, Distt. VI) Mymensingh 13. NE-30 (Jessore- Mr. Ahmad Ali Sardar Shah Abdul II) 14. NE-14 Mr. A.H.M. Kamaruzzaman Vill. Malopara, distt. (Rajshahi-III) (Hena) Rajshahi 15. NE-72 Mr. A.K.M. Fazlul Quader Goods Hill, Chittagong (Chittagong-II) chowdhury 16. NE-34 Al-haj Abd-Allah Zaheer-ud- Moiz Manzil P.O and (Faridpur-I) Deen (Lal Mian). -

Iram Sardar the Emerging British Empire and South Asia in the Eighteenth Century Abstract the Eighteenth Century Was a Time Of

Iram Sardar The Emerging British Empire and South Asia in the Eighteenth Century Abstract The eighteenth century was a time of enormous progress in Britain brought about by a vibrant economy which was the result of innovation and the growth of industry. Although domestically Britain was doing well, it faced numerous vicissitudes in its colonies. By the middle of the eighteenth century the British had become the de facto rulers of India. This was brought about by strong leadership, a robust economy and a dynamic military force. But in America it was facing numerous problems which ensued in the breakaway of the colony. Despite of so many varying occurrences globally it was able to tackle them one by one and remain on the path of progress. This upward trend as a nation was brought about because of a number of reasons which included growing economy and a relatively stable political system which was an unusual blend of Constitutional Monarchy and a Parliamentary form of government. Introduction The growth and emergences of Britain as a world power can be traced back to only a few hundred years with substantial progress taking place in the eighteenth century, with specific reference to the middle of the century from the fifties to the seventies. The insignificant island nation rose from obscurity to become the leading nation not only in Europe but the entire world. It was a time of change which lead to progress; through innovation exploration and consolidation of new colonies across the globe, stretching from the East Indies to the West Indies, a feat which had never been achieved before. -

South Asia's Lessons, Evolving Dynamics, and Trajectories

South Asia’s Lessons, Evolving Dynamics, and Trajectories Edited by Sameer Lalwani and Hannah Haegeland South Asia’s Lessons, Evolving Dynamics, and Trajectories Edited by Sameer Lalwani and Hannah Haegeland JANUARY 2018 © Copyright 2018 by the Stimson Center. All rights reserved. Printed in Washington, D.C. ISBN 978-0-9997659-0-6 Library of Congress Control Number: 2017919496 Stimson Center 1211 Connecticut Avenue, NW 8th Floor Washington, D.C. 20036 U.S.A. Visit www.stimson.org for more information about Stimson’s research. Investigating Crises: South Asia’s Lessons, Evolving Dynamics, and Trajectories CONTENTS Preface . 7 Key Terms and Acronyms . 9 Introduction . 11 Sameer Lalwani Anatomy of a Crisis: Explaining Crisis Onset in India-Pakistan Relations . 23 Sameer Lalwani & Hannah Haegeland Organizing for Crisis Management: Evaluating India’s Experience in Three Case Studies . .57 Shyam Saran Conflict Resolution and Crisis Management: Challenges in Pakistan-India Relations . 75 Riaz Mohammad Khan Intelligence, Strategic Assessment, and Decision Process Deficits: The Absence of Indian Learning from Crisis to Crisis . 97 Saikat Datta Self-Referencing the News: Media, Policymaking, and Public Opinion in India-Pakistan Crises . 115 Ruhee Neog Crisis Management in Nuclear South Asia: A Pakistani Perspective . 143 Zafar Khan China and Crisis Management in South Asia . 165 Yun Sun & Hannah Haegeland Crisis Intensity and Nuclear Signaling in South Asia . 187 Michael Krepon & Liv Dowling New Horizons, New Risks: A Scenario-based Approach to Thinking about the Future of Crisis Stability in South Asia . 221 Iskander Rehman New Challenges for Crisis Management . 251 Michael Krepon Contributors . 265 Contents 6 PREFACE With gratitude and pride I present Stimson’s latest South Asia Program book, Investigating Crises: South Asia’s Lessons, Evolving Dynamics, and Trajectories.