Restoration and Renewal Study

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Annual Report 2018/2019

Annual Report 2018/2019 Section name 1 Section name 2 Section name 1 Annual Report 2018/2019 Royal Academy of Arts Burlington House, Piccadilly, London, W1J 0BD Telephone 020 7300 8000 royalacademy.org.uk The Royal Academy of Arts is a registered charity under Registered Charity Number 1125383 Registered as a company limited by a guarantee in England and Wales under Company Number 6298947 Registered Office: Burlington House, Piccadilly, London, W1J 0BD © Royal Academy of Arts, 2020 Covering the period Coordinated by Olivia Harrison Designed by Constanza Gaggero 1 September 2018 – Printed by Geoff Neal Group 31 August 2019 Contents 6 President’s Foreword 8 Secretary and Chief Executive’s Introduction 10 The year in figures 12 Public 28 Academic 42 Spaces 48 People 56 Finance and sustainability 66 Appendices 4 Section name President’s On 10 December 2019 I will step down as President of the Foreword Royal Academy after eight years. By the time you read this foreword there will be a new President elected by secret ballot in the General Assembly room of Burlington House. So, it seems appropriate now to reflect more widely beyond the normal hori- zon of the Annual Report. Our founders in 1768 comprised some of the greatest figures of the British Enlightenment, King George III, Reynolds, West and Chambers, supported and advised by a wider circle of thinkers and intellectuals such as Edmund Burke and Samuel Johnson. It is no exaggeration to suggest that their original inten- tions for what the Academy should be are closer to realisation than ever before. They proposed a school, an exhibition and a membership. -

Restoration and Renewal of the Palace of Westminster

Availaible online at www.parliament.uk/jcpow © Parliamentary Copyright House of Lords and House of Commons 2016 OF WESTMINSTER: SESSION 2016–17: FROM THE JOINT COMMITTEE ON PALACE FIRST REPORT This publication may be reproduced under the terms of the Open Parliament Licence, which is published at www.parliament.uk/site-information/copyright House of Lords House of Commons Joint Committee on the Palace of Westminster Restoration and Renewal of the Palace of Westminster First Report of Session 2016–17 HL Paper 41 HC 659 HL Paper 41 HC 659 House of Lords House of Commons Joint Committee on the Palace of Westminster Restoration and Renewal of the Palace of Westminster First Report of Session 2016–17 Report, together with formal minutes relating to the report Ordered by the House of Lords to be printed on 5 September 2016 Ordered by the House of Commons to be printed on 5 September 2016 HL Paper 41 HC 659 Published on 8 September 2016 by authority of the House of Lords and House of Commons Joint Committee on the Palace of Westminster The Joint Committee on the Palace of Westminster was appointed in July 2015 to consider the restoration and renewal of the Palace of Westminster. The House of Commons Members were appointed on 16 July 2015. The House of Lords Members were appointed on 20 July 2015 and reappointed on 25 May 2016. Membership HOUSE OF LORDS HOUSE OF COMMONS Baroness Stowell of Beeston (Conservative) Chris Grayling MP (Conservative) (Co-Chairman) (Co-Chairman) Lord Carter of Coles (Labour) Chris Bryant MP (Labour) Lord Deighton (Conservative) -

Masterworks Architecture at the Masterworks: Royal Academy of Arts Neil Bingham

Masterworks Architecture at the Masterworks: Royal Academy of Arts Neil Bingham Royal Academy of Arts 2 Contents President’s Foreword 000 Edward Middleton Barry ra (1869) 000 Sir Howard Robertson ra (1958) 000 Paul Koralek ra (1991) 000 Preface 000 George Edmund Street ra (1871) 000 Sir Basil Spence ra (1960) 000 Sir Colin St John Wilson ra (1991) 000 Acknowledgements 000 R. Norman Shaw ra (1877) 000 Donald McMorran ra (1962) 000 Sir James Stirling ra (1991) 000 John Loughborough Pearson ra (1880) 000 Marshall Sisson ra (1963) 000 Sir Michael Hopkins ra (1992) 000 Architecture at the Royal Academy of Arts 000 Alfred Waterhouse ra (1885) 000 Raymond Erith ra (1964) 000 Sir Richard MacCormac ra (1993) 000 Sir Thomas Graham Jackson Bt ra (1896) 000 William Holford ra, Baron Holford Sir Nicholas Grimshaw pra (1994) 000 The Architect Royal Academicians and George Aitchison ra (1898) 000 of Kemp Town (1968) 000 Michael Manser ra (1994) 000 Their Diploma Works 000 George Frederick Bodley ra (1902) 000 Sir Frederick Gibberd ra (1969) 000 Eva M. Jiricna ra (1997) 000 Sir William Chambers ra (1768, Foundation Sir Aston Webb ra (1903) 000 Sir Hugh Casson pra (1970) 000 Ian Ritchie ra (1998) 000 Member, artist’s presentation) 000 John Belcher ra (1909) 000 E. Maxwell Fry ra (1972) 000 Will Alsop ra (2000) 000 George Dance ra (1768, Foundation Member, Sir Richard Sheppard ra (1972) 000 Gordon Benson ra (2000) 000 no Diploma Work) 000 Sir Reginald Blomfield ra (1914) 000 H. T. Cadbury-Brown ra (1975) 000 Piers Gough ra (2001) 000 John Gwynn ra (1768, Foundation Member, Sir Ernest George ra (1917) 000 no Diploma Work) 000 Ernest Newton ra (1919) 000 Ernö Goldfinger ra (1975) 000 Sir Peter Cook ra (2003) 000 Thomas Sandby ra (1768, Foundation Member, Sir Edwin Lutyens pra (1920) 000 Sir Philip Powell ra (1977) 000 Zaha Hadid ra (2005) 000 bequest from great-grandson) 000 Sir Giles Gilbert Scott ra (1922) 000 Peter Chamberlin ra (1978) 000 Eric Parry ra (2006) 000 William Tyler ra (1768, Foundation Member, Sir John J. -

Westminster World Heritage Site Management Plan Steering Group

WESTMINSTER WORLD HERITAGE SITE MANAGEMENT PLAN Illustration credits and copyright references for photographs, maps and other illustrations are under negotiation with the following organisations: Dean and Chapter of Westminster Westminster School Parliamentary Estates Directorate Westminster City Council English Heritage Greater London Authority Simmons Aerofilms / Atkins Atkins / PLB / Barry Stow 2 WESTMINSTER WORLD HERITAGE SITE MANAGEMENT PLAN The Palace of Westminster and Westminster Abbey including St. Margaret’s Church World Heritage Site Management Plan Prepared on behalf of the Westminster World Heritage Site Management Plan Steering Group, by a consortium led by Atkins, with Barry Stow, conservation architect, and tourism specialists PLB Consulting Ltd. The full steering group chaired by English Heritage comprises representatives of: ICOMOS UK DCMS The Government Office for London The Dean and Chapter of Westminster The Parliamentary Estates Directorate Transport for London The Greater London Authority Westminster School Westminster City Council The London Borough of Lambeth The Royal Parks Agency The Church Commissioners Visit London 3 4 WESTMINSTER WORLD HERITAGE S I T E M ANAGEMENT PLAN FOREWORD by David Lammy MP, Minister for Culture I am delighted to present this Management Plan for the Palace of Westminster, Westminster Abbey and St Margaret’s Church World Heritage Site. For over a thousand years, Westminster has held a unique architectural, historic and symbolic significance where the history of church, monarchy, state and law are inexorably intertwined. As a group, the iconic buildings that form part of the World Heritage Site represent masterpieces of monumental architecture from medieval times on and which draw on the best of historic construction techniques and traditional craftsmanship. -

I'm Lovin' It: a Call to Restore Valletta's Opera House

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Nottingham Trent Institutional Repository (IRep) Sunday, April 15, 2007 , by Stuart Burch I'm lovin' it: a call to restore Valletta's Opera House It is remarkable that one of Malta's most famous and well recognised buildings is in a state of almost total destruction. I am referring, of course, to the Royal Opera House in Valletta. Its image appears in countless books and Websites. It acts like a time machine propelling us back to various points in history. The version we see today bears all the hallmarks of the Luftwaffe attack of April 7, 1942. This left the building a smoking shell. The smoke might have cleared but the shell still remains. In this article I wish to add my voice to those who favour permanently keeping this architectural skeleton and explain why I believe it should be 'restored'. This is first and foremost because the Opera House has had such an exceptionally eventful history. Its fateful story began long before the Luftwaffe menaced the skies of Malta. A sign of things to come occurred a few years after its inauguration in 1866 when the building was gutted by fire. Joseph Bonnici and Michael Cassar's fascinating book on The Royal Opera House (1990) relates this and many other stories, revealing in the process that controversy and disaster has stalked the building from the very moment it was conceived. This was perhaps inevitable, given that the architect was Edward Middleton Barry (1830-80). -

Out and About in Halifax 1863-2013

Out and About in Halifax 1863-2013 John A. Hargreaves The 150th anniversary of Halifax Town Hall in 2013 provides an opportunity to explore the rich heritage of this Pennine town as did its first British royal visitor in 1863 The former Victorian carpet and worsted mills of the Crossleys and Akroyds dominate this photograph of Dean Clough, now an interface for business and the arts, whilst the soaring spire of George Gilbert Scott’s masterpiece, All Souls’ Church penetrates the skyline. ©English Heritage t was unusual for the national press in the view of the Chartist historian press with the Illustrated London News Ito descend on Halifax, as they did F.C. Mather, regular troops had come reporter commenting disparagingly on 3 and 4 August 1863, but The Times, nearer to being overwhelmed by the on the muddy streets surrounding the Illustrated London News and the rioters in Halifax than anywhere else the Piece Hall. Indeed, The Times Illustrated Times were determined to in the Chartist era. Indeed, twenty-one reporter was prompted to opine that cover the first official visit to a northern years later, a superintendent of police Halifax might be considered to have mill town of the newly married Prince was imported from London with twelve been ‘deficient, as a general rule, in and Princess of Wales for the opening inspectors, 200 hand-picked officers and what Londoners would call streets’ of Halifax’s magnificent new Town additional police reinforcements drafted except perhaps for those recently Hall. This imposing neo-renaissance in from across the West Riding and the improved by the carpet manufacturer, building had been designed by no less North West to strengthen security for the John Crossley, the Mayor of Halifax, a figure than Sir Charles Barry, the royal visit, which occurred just ten years in the immediate vicinity of the Town architect of the reconstructed Palace of after the final Chartist demonstration Hall. -

BULLETIN Vol 49 No 4 July / August 2015

CINEMA THEATRE ASSOCIATION BULLETIN www.cta-uk.org Vol 49 No 4 July / August 2015 The grade II listed Ritz at Grays (Essex), where bingo is about to close, photographed in April 2004 – see Newsreel p19 Two views of just part of the Projected Picture Trust’s collection in its new home in Halifax – see Newsreel p18 FROM YOUR EDITOR CINEMA THEATRE ASSOCIATION promoting serious interest in all aspects of cinema buildings It doesn’t seem two minutes since I was writing the last editorial; —————————— time seems to come around so quickly. We have just returned from Company limited by guarantee. Reg. No. 04428776. Registered address: 59 Harrowdene Gardens, Teddington, TW11 0DJ. the CTA visit to Winchester, where we had an enjoyable – if hectic – Registered Charity No. 1100702. Directors are marked ‡ in list below. day; there will be a full report in the next Bulletin. We travelled down —————————— via Nuneaton and returned via Oxford. In both places I was able to PATRONS: Carol Gibbons Glenda Jackson CBE photograph some former cinemas I had not seen before to add to my Sir Gerald Kaufman PC MP Lucinda Lambton —————————— collection. There are still some I have missed in odd areas of the ANNUAL MEMBERSHIP SUBSCRIPTIONS country and I aim to try to get these over the next few years. Full Membership (UK) ................................................................ £29 On a recent visit to Hornsea (East Yorkshire) the car screeched to a Full Membership (UK under 25s) .............................................. £15 halt when I saw the building pictured below. It looked to have cine- Overseas (Europe Standard & World Economy) ........................ £37 matic features but I could only find references in the KYBs to the Star Overseas (World Standard) ....................................................... -

Full Version

Západo česká univerzita v Plzni Fakulta filozofická Bakalá řská práce 2012 Lenka Van čurová Západo česká univerzita v Plzni Fakulta filozofická Bakalá řská práce A TOURIST GUIDE OF VICTORIAN LONDON WITH ENGLISH-CZECH DICTIONARY OF KEY TERMS Lenka Van čurová Plze ň 2012 Západo česká univerzita v Plzni Fakulta filozofická Katedra anglického jazyka a literatury Studijní program Filologie Studijní obor Cizí jazyky pro komer ční praxi angli čtina - němčina Bakalá řská práce A TOURIST GUIDE OF VICTORIAN LONDON WITH ENGLISH-CZECH DICTIONARY OF KEY TERMS Lenka Van čurová Vedoucí práce: Mgr. Jana Kašparová Katedra anglického jazyka a literatury Fakulta filozofická Západo české univerzity v Plzni Plze ň 2012 Acknowledgments I would like to thank my supervisor Mgr. Jana Kašparová for her time and suggestions on the style of writing. I wish also thank Royal Albert Hall archives for sending me the photographs of construction of Royal Albert Hall. Prohlašuji, že jsem práci zpracovala samostatn ě a použila jen uvedených pramen ů a literatury. Plze ň, duben 2012 ……………………… 1 INTRODUCTION ................................................................................. 1 2 HISTORICAL BACKGROUND OF VICTORIAN ERA ................. 3 The longest reigning British monarch ........................................................................ 3 Victorian London - city of contrasts ........................................................................... 4 Poverty in the streets .................................................................................................. -

Chairman's Report

Newsletter No. 101 – May 2021 Free to members Chairman’s Report In this Issue: Bob Flanagan John Bazley Good news this month is that restoration of the monu- White (1784- ment to dramatist and judge Sir Thomas Noon Talfourd 1867): Solid (1795–1854; grave 1,452, square 34) has been completed save for work on the brickwork that will be finished once Foundations (if) the weather improves. The elegant cross atop the Page 5 monument had been demolished and the vault damaged The Mabey by a falling tree (see Newsletter 87, September 2016). Sculptors : An Thanks to the Old Reding- Immense ensians Association, the Dickens Fellowship, Kev- Contribution in Crook & Jacqueline Page 10 Landy (Lambeth) and to monumental masons Row- The Curlings, land Brothers. They have The Hunters, as always done an ex- and the Dunns cellent job! Page 14 Other news is that the con- Tidying-up the tract for the roadways and drainage package of the Cemetery NHLF grant has been aw- Page 15 arded to idverde UK Ltd. However, seemingly work Forthcoming cannot start until May at Events Page 15 the earliest. Inevitably this work will be disruptive, A Bit of Mystery but a one-way traffic sys- Page 16 tem is being planned that should allow unimpeded access to all parts of the cemetery. The restored Talfourd cross Planning for the new entrances on Robson Road and at Hubbard Road continues. At Hubbard Road it is apparent that one of the original gateposts has been hit recently by a high-sided vehicle. The damage will be repaired as part of the works to enable this entrance to be reopened. -

Jlriend£ of Te{E£F 12Orwood Jlemefery

Jlriend£ of te{e£f 12orwood jlemefery NEWSLETTER NO.14: APRIL 1993 Chairman's Report - Bob Flanagan Thus, if we agree to cooperate in formulating future Lambeth's draft Land Management Strategy (the long plans for the cemetery whilst believing past actions awaited report) on the future of the cemetery was to be unlawful we could be considered 'accessories• presented to the Environmental Services Committee after-the-fact' and thus could be seen as condoning at their February meeting and was then to be circu• unlawful acts if an action were ever brought. lated for discussion to interested parties. Lam beth immediately issued a Press Release highlighting their This is independent of any considerations of faculty plan 'to preserve the cemetery as a 'historic con• jurisdiction - Lambeth have demolished thousands of servation site'. This was swallowed whole by the monuments in the consecrated parts of the cemetery Dulwich Guardian who ran a front page lead on the without a faculty from the Church authorities. Again report on 11 March. the report makes no mention of this fact and thus there is no discussion of how the situation is to be The South London Press was more cautious (more addressed. We suggest that a map showing precisely experienced?) and contacted our Vice-Chairman the consecrated parts of the cemetery is needed as a Nicholas Long who had meanwhile managed to first step. obtain a copy of the document in question. It took Nicholas no time at all to point out the many serious Despite the Lambeth press release emphasizing the flaws in the Lambeth document and also that it was historic impOltance of the cemetery, the report in fact some 15 years or so late. -

A Self-Guided Walk Around West Norwood Cemetery

Lives of the dead A self-guided walk around West Norwood Cemetery Explore one of London’s ‘Magnificent Seven’ cemeteries Discover why it was built and Victorian attitudes to death Find out about about some of the famous people buried there .discoveringbritain www .org ies of our land the stor scapes throug discovered h walks Created in collaboration with 2 Contents Introduction 4 Route map 5 Practical information 6 Commentary 8 Further information 46 Credits 47 © The Royal Geographical Society with the Institute of British Geographers, London, 2014 Discovering Britain is a project of the Royal Geographical Society (with IBG) The digital and print maps used for Discovering Britain are licensed to the RGS-IBG from Ordnance Survey Cover image: Memorials in the Greek necropolis © Rory Walsh 3 Lives of the dead Discover how people from around the world found peace in south London Welcome to this Discovering Britain walk in West Norwood Cemetery. West Norwood was one of seven private cemeteries founded on the outskirts of London in the nineteenth century, when life expectancy was short and burial space scarce. This walk explores the cemetery to find out more about some of the View of the South Metropolitan Cemetery (1891) notable people buried here. © London Borough of Lambeth From Victorian household names to post Second World War migrants, people from many walks of life and from many countries around the world have their final resting place in West Norwood. They include royals, inventors, artists, writers, soldiers and sports heroes. On this walk you can discover some of their incredible monuments and hear their fascinating stories. -

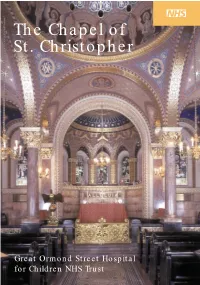

The Chapel of St. Christopher

chapel a5 booklet 14/3/02 3:42 pm Page 1 The Chapel of St. Christopher Great Ormond Street Hospital for Children NHS Trust chapel a5 booklet 14/3/02 3:42 pm Page 2 St.St. ChristopherChristopher’’ss ChapChap Background Designed by Edward Middleton Barry, third On the north and south walls are two large son of Sir Charles Barry (architect with mural paintings and to the left and right of A.W.N. Pugin of the Houses of Parliament), the door are the figures of St. Peter and St. the Chapel was originally an integral part of Paul. Note that the children in the picture on the old hospital building. Completed in 1875, the north wall are wearing clothes of many it is dedicated to the memory of Caroline, centuries, one little girl looking very much wife of William Henry Barry (eldest son of Sir like Alice in Wonderland. (The Tenniel Charles Barry) who gave £40,000 for the illustrations of Lewis Carroll’s work were building of the Chapel and provided a stipend produced in 1865, just a few years before for the chaplain. these murals were painted). In the Byzantine idiom, the Chapel is of The Sanctuary is approached through a relatively modest dimensions, though the magnificent pair of fine brass gates with glass immediate impression is of a much larger ornamentation in a low marble screen with building – an effect created by the excellence inset brass decoration. Note also the splendid of the architectural proportions and the eagle lectern. grandeur of the decorations. It is a real ‘tour The stained glass depicts the Nativity, the de force’ of high Victorian ecclesiastical style, childhood of Christ and biblical scenes and arguably the most sumptuous hospital connected with children, and above is a series chapel in the country.