Muhammad Asad's Approach to Shari'ah: an Exposition

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Reconstruction of Religious Thought in Islam

The Reconstruction of Religious Thought in Islam Muhammad Iqbal The Reconstruction of Religious Thought in Islam written by Muhammad Iqbal Published in 1930. Copyright © 2009 Dodo Press and its licensors. All Rights Reserved. CONTENTS • Preface • Knowledge and Religious Experience • The Philosophical Test of the Revelations of Religious Experience • The Conception of God and the Meaning of Prayer • The Human Ego - His Freedom and Immortality • The Spirit of Muslim Culture • The Principle of Movement in the Structure of Islam • Is Religion Possible? PREFACE The Qur‘an is a book which emphasizes ‘deed‘ rather than ‘idea‘. There are, however, men to whom it is not possible organically to assimilate an alien universe by re-living, as a vital process, that special type of inner experience on which religious faith ultimately rests. Moreover, the modern man, by developing habits of concrete thought - habits which Islam itself fostered at least in the earlier stages of its cultural career - has rendered himself less capable of that experience which he further suspects because of its liability to illusion. The more genuine schools of Sufism have, no doubt, done good work in shaping and directing the evolution of religious experience in Islam; but their latter-day representatives, owing to their ignorance of the modern mind, have become absolutely incapable of receiving any fresh inspiration from modern thought and experience. They are perpetuating methods which were created for generations possessing a cultural outlook differing, in important respects, from our own. ‘Your creation and resurrection,‘ says the Qur‘an, ‘are like the creation and resurrection of a single soul.‘ A living experience of the kind of biological unity, embodied in this verse, requires today a method physiologically less violent and psychologically more suitable to a concrete type of mind. -

The Layha for the Mujahideen: an Analysis of the Code of Conduct for the Taliban Fighters Under Islamic Law

Volume 93 Number 881 March 2011 The Layha for the Mujahideen:an analysis of the code of conduct for the Taliban fighters under Islamic law Muhammad Munir* Dr.Muhammad Munir is Associate Professor and Chairman,Department of Law, Faculty of Shari‘a and Law, International Islamic University, Islamabad. Abstract The following article focuses on the Islamic Emirate of Afghanistan Rules for the Mujahideen** to determine their conformity with the Islamic jus in bello. This code of conduct, or Layha, for Taliban fighters highlights limiting suicide attacks, avoiding civilian casualties, and winning the battle for the hearts and minds of the local civilian population. However, it has altered rules or created new ones for punishing captives that have not previously been used in Islamic military and legal history. Other rules disregard the principle of distinction between combatants and civilians and even allow perfidy, which is strictly prohibited in both Islamic law and international humanitarian law. The author argues that many of the Taliban rules have only a limited basis in, or are wrongly attributed to, Islamic law. * The help of Andrew Bartles-Smith, Prof. Brady Coleman, Major Nasir Jalil (retired), Ahmad Khalid, and Dr. Marty Khan is acknowledged. The quotations from the Qur’an in this work are taken, unless otherwise indicated, from the English translation by Muhammad Asad, The Message of the Qur’an, Dar Al-Andalus, Redwood Books, Trowbridge, Wiltshire, 1984, reprinted 1997. ** The full text of the Layha is reproduced as an annex at the end of this article. doi:10.1017/S1816383111000075 81 M. Munir – The Layha for the Mujahideen: an analysis of the code of conduct for the Taliban fighters under Islamic law Do the Taliban qualify as a ‘non-state armed group’? Since this article deals with the Layha,1 it is important to know whether the Taliban in Afghanistan, as a fighting group, qualify as a ‘non-state Islamic actor’. -

Muhammad Asad and International Islamic Colloquium of 1957-58: a Forgotten Chapter from the History of the Punjab University

Muhammad Asad and International Islamic Colloquium of 1957-58: A Forgotten Chapter from the History of the Punjab University Dr. Zahid Munir Amir ABSTRACT: This paper deals with the contribution of Muhammad Asad in international Islamic Colloquium held at the Punjab University, Lahore, Pakistan, from 29 December 1957 to 8 January 1958, which can be considered the first International activity on Islamization after World War II. In spite of Mr Asad’s notable contribution to this colloquium, his name has never been mentioned in this context. This paper discovers some official documents regarding his role in this perspective. Mr. Asad’s contribution in establishing a new department of Islamic Studies in the oldest seat of learning in South Asia i.e. University of the Punjab is also discussed at length. Keywords: History of Punjab University, Muhammad Asad, Leopold Weiss, International Islamic Colloqium Journal of Research (Humanities) 2 Muhammad Asad was born in a Polish family at Limburg (present day Ukraine), on 2 July 1900. His original name was Leopold Weiss. He learnt the Jewish Holy Scriptures and the Hebrew language at an early age. His family shifted to Vienna in 1914 where he continued his learning. In 1918, he joined the Austrian army. He studied philosophy, history, art, physics and chemistry from the Vienna University. In 1922, he traveled to the Middle East for the first time and visited Egypt, Jordan, Palestine, Syria and Turkey. During his second travel in 1924, he went to Egypt, Amman, Tripoli, Iraq, Iran, Afghanistan and the Central Asia. After long experience, deep observation and extensive study, he embraced Islam in 1926 at Berlin and adopted Muhammad Asad as his Islamic name. -

Marshall Communicatingthewo

COMMUNICATING THE WORD Previously Published Records of Building Bridges Seminars The Road Ahead: A Christian-Muslim Dialogue, Michael Ipgrave, Editor (Church House Publishing) Scriptures in Dialogue: Christians and Muslims Studying the Bible and the Qur’a¯n Together, Michael Ipgrave, Editor (Church House Publishing) Bearing the Word: Prophecy in Biblical and Qur’a¯nic Perspective, Michael Ipgrave, Editor (Church House Publishing) Building a Better Bridge: Muslims, Christians, and the Common Good, Michael Ipgrave, Editor (Georgetown University Press) Justice and Rights: Christian and Muslim Perspectives, Michael Ipgrave, Editor (Georgetown University Press) Humanity: Texts and Contexts: Christian and Muslim Perspectives, Michael Ipgrave and David Marshall, Editors (Georgetown University Press) For more information about the Building Bridges seminars, please visit http://berkleycenter.georgetown.edu/networks/building_bridges Communicating the Word Revelation, Translation, and Interpretation in Christianity and Islam A record of the seventh Building Bridges seminar Convened by the Archbishop of Canterbury Rome, May 2008 DAVID MARSHALL, EDITOR georgetown university press Washington, DC ᭧ 2011 Georgetown University Press. All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or utilized in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying and recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Communicating the word : revelation, translation, and interpretation in Christianity and Islam : a record of the seventh Building Bridges seminar convened by the Archbishop of Canterbury, Rome, May 2008 / David Marshall, editor. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-1-58901-784-9 (pbk. : alk. paper) 1. -

Self Discovery with Talent Management Achieving Excellence in Your Professional Career Resource Person: Engr

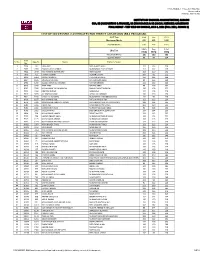

Webinar Titled: Self Discovery With Talent Management Achieving Excellence in Your Professional Career Resource Person: Engr. Prof. Dr. Bhawani Shankar Chowdhry Dated: 7-5-2021 Certificate Sr# PEC Reg No. Name CPD Points Serial 1 54551 CIVIL/50600 Muhammad Zahid Saeed 0.5 2 54552 CIVIL/49863 Muhammad Safeer 0.5 3 54553 CIVIL/50354 Aftab Alam 0.5 4 54554 CIVIL/49741 Shayan Afsar 0.5 5 54555 MECH/39680 Salim Akhtar 0.5 6 54556 TEXTILE/03066 rajesh kumar 0.5 7 54557 ELECT/70876 Muhammad Luqman 0.5 8 54558 CHEM/17296 MUHAMMAD ANUS 0.5 9 54559 CIVIL/49460 Abdul Qadeer 0.5 10 54560 CIVIL/50304 SYED YASIR HUSSAIN 0.5 11 54561 MECH/39528 Abubakr Shahnawaz Kamil 0.5 12 54562 CIVIL/49536 Allah Yar Khan 0.5 13 54563 CHEM/17535 SHAHBAZ AHMED KHAN 0.5 14 54564 METAL/05179 FAHIM ULLAH JAN 0.5 15 54565 ELECT/72503 Sabien irshad 0.5 16 54566 CIVIL/49494 MUHAMMAD ZEESHAN 0.5 17 54567 ELECTRO/27870 Rehan Ali Hasani 0.5 18 54568 ELECT/71041 M Hamza Ahmad 0.5 19 54569 CIVIL/50569 Hafiz Zeeshan Zia 0.5 20 54570 CIVIL/49986 SHAHZADA MUHAMMAD ZULQERNAIN 0.5 21 54571 AGRI/05372 Faiz Ul Haq 0.5 22 54572 AGRI/05368 MUHAMMAD HAMZA 0.5 23 54573 CIVIL/49529 Rizwan Muhammad 0.5 24 54574 CIVIL/49604 Shahid Saeed 0.5 25 54575 METAL/05231 FARHAN ALI 0.5 26 54576 AGRI/05417 Muhammad Luqman ur Rehman 0.5 27 54577 MECH/39060 Muhammad Muddasar 0.5 28 54578 ELECT/71685 Waqar Ahmed 0.5 29 54579 TRANSPORT/00326 Muhammad Arslan Ali 0.5 30 54580 MECH/38930 Ghulam Yaseen 0.5 31 54581 CIVIL/49470 Haider Abbas 0.5 32 54582 ELECT/71683 ASAD ALI 0.5 33 54583 CIVIL/49445 Abdul Haseeb -

Announced on Monday, July 19, 2021

FINAL RESULT - FALL 2021 ROUND 2 Announced on Monday, July 19, 2021 INSTITUTE OF BUSINESS ADMINISTRATION, KARACHI BBA, BS (ACCOUNTING & FINANCE), BS (ECONOMICS) & BS (SOCIAL SCIENCES) ADMISSIONS FINAL RESULT ‐ TEST HELD ON SUNDAY, JULY 4, 2021 (FALL 2021, ROUND 2) LIST OF SUCCESSFUL CANDIDATES FOR DIRECT ADMISSION (BBA PROGRAM) SAT Test Math Eng TOTAL Maximum Marks 800 800 1600 Cut-Off Marks 600 600 1420 Math Eng Total IBA Test MCQ MCQ MCQ Maximum Marks 180 180 360 Cut-Off Marks 88 88 224 Seat S. No. App No. Name Father's Name No. 1 7904 30 LAIBA RAZI RAZI AHMED JALALI 112 116 228 2 7957 2959 HASSAAN RAZA CHINOY MUHAMMAD RAZA CHINOY 112 132 244 3 7962 3549 MUHAMMAD SHAYAN ARIF ARIF HUSSAIN 152 120 272 4 7979 455 FATIMA RIZWAN RIZWAN SATTAR 160 92 252 5 8000 1464 MOOSA SHERGILL FARZAND SHERGILL 124 124 248 6 8937 1195 ANAUSHEY BATOOL ATTA HUSSAIN SHAH 92 156 248 7 8938 1200 BIZZAL FARHAN ALI MEMON FARHAN MEMON 112 112 224 8 8978 2248 AFRA ABRO NAVEED ABRO 96 136 232 9 8982 2306 MUHAMMAD TALHA MEMON SHAHID PARVEZ MEMON 136 136 272 10 9003 3266 NIRDOSH KUMAR NARAIN NA 120 108 228 11 9017 3635 ALI SHAZ KARMANI IMTIAZ ALI KARMANI 136 100 236 12 9031 1945 SAIFULLAH SOOMRO MUHAMMAD IBRAHIM SOOMRO 132 96 228 13 9469 1187 MUHAMMAD ADIL RAFIQ AHMAD KHAN 112 112 224 14 9579 2321 MOHAMMAD ABDULLAH KUNDI MOHAMMAD ASGHAR KHAN KUNDI 100 124 224 15 9582 2346 ADINA ASIF MALIK MOHAMMAD ASIF 104 120 224 16 9586 2566 SAMAMA BIN ASAD MUHAMMAD ASAD IQBAL 96 128 224 17 9598 2685 SYED ZAFAR ALI SYED SHAUKAT HUSSAIN SHAH 124 104 228 18 9684 526 MUHAMMAD HAMZA -

Muhammad Asad's Views on Shari'ah

JURNAL HAL EHWAL ISLAM DAN WARISAN SELANGOR E-ISSN 2600-7509 BIL 3 NO. 2 2018 Muhammad Asad’s Views on Shari‘ah Ahmad Nabil Amir [email protected] Islamic Renaissance Front, Pavilion KL, 168 Jalan Bukit Bintang, 55100 Kuala Lumpur, Wilayah Persekutuan, Malaysia ABSTRACT This paper analyzed Muhammad Asad’s (1900-1992) views on Shari‘ah (Islamic law). This was investigated from his thoughtful and broad understanding of its principle and underlying purpose. The essential understanding of the principle of shariah was analytically discussed in his works such as This Law of Ours and Other Essays, The Principles of State and Government in Islam and in his magnum opus The Message of the Qur’an. The finding shows that Muhammad Asad’s discussion on shariah emphasized on its dynamic principle and relevance to contemporary practice and modern context of Islam. It set forth important framework towards reforming Islamic law by critically reconstructing and reprojecting its ideal in order to establish justice in implementing the law and in framing the ideal that underlie its purpose. Keyword: Muhammad Asad, shariah, the practice of law, higher purpose of Islamic law Pandangan Muhammad Asad tentang Shari‘ah ABSTRAK Kertas ini menganalisis pandangan Muhammad Asad tentang Shariah Islam. Ini ditinjau dari kerangka pemikirannya yang luas yang menzahirkan falsafah dan idealisme maqasid dan fiqh syariah yang mendasar. Kefahaman tentang prinsip hukum dan shariah dan implikasinya dalam pemikiran moden ini dibahaskan dengan mendalam dalam karya-karyanya seperti This Law of Ours and Other Essays, The Principles of State and Government in Islam dan dalam magnum opusnya The Message of the Qur’an. -

Defining Shariʿa the Politics of Islamic Judicial Review by Shoaib

Defining Shariʿa The Politics of Islamic Judicial Review By Shoaib A. Ghias A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the Requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Jurisprudence and Social Policy in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in Charge: Professor Malcolm M. Feeley, Chair Professor Martin M. Shapiro Professor Asad Q. Ahmed Summer 2015 Defining Shariʿa The Politics of Islamic Judicial Review © 2015 By Shoaib A. Ghias Abstract Defining Shariʿa: The Politics of Islamic Judicial Review by Shoaib A. Ghias Doctor of Philosophy in Jurisprudence and Social Policy University of California, Berkeley Professor Malcolm M. Feeley, Chair Since the Islamic resurgence of the 1970s, many Muslim postcolonial countries have established and empowered constitutional courts to declare laws conflicting with shariʿa as unconstitutional. The central question explored in this dissertation is whether and to what extent constitutional doctrine developed in shariʿa review is contingent on the ruling regime or represents lasting trends in interpretations of shariʿa. Using the case of Pakistan, this dissertation contends that the long-term discursive trends in shariʿa are determined in the religio-political space and only reflected in state law through the interaction of shariʿa politics, regime politics, and judicial politics. The research is based on materials gathered during fieldwork in Pakistan and datasets of Federal Shariat Court and Supreme Court cases and judges. In particular, the dissertation offers a political-institutional framework to study shariʿa review in a British postcolonial court system through exploring the role of professional and scholar judges, the discretion of the chief justice, the system of judicial appointments and tenure, and the political structure of appeal that combine to make courts agents of the political regime. -

Mohammad N. Miraly Faculty of Religious Studies Mcgill University, Montreal April 2012

FAITH AND WORLD CONTEMPORARY ISMAILI SOCIAL AND POLITICAL THOUGHT Mohammad N. Miraly Faculty of Religious Studies McGill University, Montreal April 2012 A thesis submitted to McGill University in partial fulfillment of the requirements of the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Religious Studies © 2012 Mohammad N. Miraly TO MY F ATHER AND M OTHER TABLE OF CONTENTS Abstract i Résumé iii Acknowledgements v An Historical Note on Ismailism vii 1 Opening 1 2 The Study 15 Part I: 3 Speaking About Ismailism 24 4 The Contemporary Ismaili Historical Narrative 59 5 Ismaili Approaches to the Qur’an 103 6 The AKDN in Afghanistan: Ethos and Praxis 114 Part II: 7 Democracy, Secularism, and Social Ethics 138 8 Pluralism and Civic Culture 159 9 Knowledge and Learning 185 10 Closing: The Transnational Ismaili in Canada 202 Postscript: Wither Neutrality? 213 Appendix A: Preamble to the Constitution of the Shi`a Imami Ismaili Muslims 216 Appendix B: AKDN Organisation Chart 218 Selected Bibliography 219 ABSTRACT Contemporary Ismaili thought views the Ismaili tradition as connected to a historical past deriving from Qur’anic principles and the teachings of the Prophet Muhammad and his heirs, the Shi`a Imams. Thus, contemporary Ismailism’s focus on liberal values like democracy, pluralism, and education are articulated as contemporary forms of eternal Qur’anic ethical principles. The current and 49th Ismaili Imam, Aga Khan IV – who claims descent from the Prophet through his daughter, Fatima, and son-in-law, `Ali – articulates the principles of liberal democratic pluralism as the best means to realize ethical Islamic living in the present day. -

Air University

Campus Department Year Of Study Full Name Father Name CNIC Degree Title CGPA Student Selection Status Merit Status Main campus Business Administration 1 Ayesha Khalid Khalid Rasheed 6110192944730 BS (Hons) 3.41 Selected Student Eligible Main campus Business Administration 1 Aqsa Shazad Shahzad Muhammad Khan 6110197312776 BBA 3.5 Selected Student Eligible Main campus Business Administration 1 Syed Ammar Ali Syed Asghar Ali Shah 6110172874109 BBA 3.39 Selected Student Eligible Main campus Business Administration 1 sarah shahid shahid nazir ahmed 6110108155772 BBA 3.58 Selected Student Eligible Main campus Business Administration 1 SAHAR WAQAR WAQAR UL MULK 1330115037462 BBA 3.64 Selected Student Eligible Main campus Business Administration 1 Lubna Nawaz Muhammad Nawaz 3740276933200 BBA 3.64 Selected Student Eligible Main campus Business Administration 1 Nida Ulfat Khadim Hussain 3110483904208 BBA 3.45 Selected Student Eligible Main campus Business Administration 1 MUHAMMAD BILAL HANIF MUHAMMAD HANIF 6110114197095 BBA 3.33 Selected Student Eligible Main campus Business Administration 1 Choudhary Asad Latif Choudhary Farrukh Ubaid 3740522439729 BS (Hons) 3.64 Selected Student Eligible Main campus Business Administration 1 Laraib Ashfaq Mughal Muhammad Ashfaq Mughal 3740553476114 BS (Hons) 3.59 Selected Student Eligible Main campus Business Administration 1 ShalaleNoor Mohammad Azhar Hussain Butt 6110185989724 BBA 3.64 Selected Student Eligible Main campus Business Administration 1 Hammad Ahmad Khan Ahmad Khan 3840331123547 BS (Hons) 3.44 Selected -

6455.Pdf, PDF, 1.27MB

Overall List Along With Domicile and Post Name Father Name District Post Shahab Khan Siraj Khan PESHAWAR 01. Station House Incharge (BPS-16) Sana Ullah Muhammad Younas Lower Dir 01. Station House Incharge (BPS-16) Mahboob Ali Fazal Rahim Swat 01. Station House Incharge (BPS-16) Tahir Saeed Saeed Ur Rehman Kohat 01. Station House Incharge (BPS-16) Owais Qarni Raham Dil Lakki Marwat 01. Station House Incharge (BPS-16) Ashfaq Ahmad Zarif Khan Charsadda 01. Station House Incharge (BPS-16) Saud Khan Haji Minak Khan Khyber 01. Station House Incharge (BPS-16) Qamar Jan Syed Marjan Kurram 01. Station House Incharge (BPS-16) Kamil Khan Wakeel Khan PESHAWAR 01. Station House Incharge (BPS-16) Waheed Gul Muhammad Qasim Lakki Marwat 01. Station House Incharge (BPS-16) Tanveer Ahmad Mukhtiar Ahmad Mardan 01. Station House Incharge (BPS-16) Muhammad Faheem Muhammad Aslam PESHAWAR 01. Station House Incharge (BPS-16) Muslima Bibi Jan Gul Dera Ismail Khan 01. Station House Incharge (BPS-16) Muhammad Zahid Muhammad Saraf Batagram 01. Station House Incharge (BPS-16) Riaz Khan Muhammad Anwar Lower Dir 01. Station House Incharge (BPS-16) Bakht Taj Abdul Khaliq Shangla 01. Station House Incharge (BPS-16) Hidayat Ullah Fazal Ullah Swabi 01. Station House Incharge (BPS-16) Wajid Ali Malang Jan Mardan 01. Station House Incharge (BPS-16) Sahar Rashed Abdur Rasheed Mardan 01. Station House Incharge (BPS-16) Afsar Khan Afridi Ghulam Nabi PESHAWAR 01. Station House Incharge (BPS-16) Adnan Khan Manazir Khan Mardan 01. Station House Incharge (BPS-16) Liaqat Ali Malik Aman Charsadda 01. Station House Incharge (BPS-16) Adnan Iqbal Parvaiz Khan Mardan 01. -

Chapter Ii Sihr Or Black Magic and It's Original History A

Edited with the trial version of Foxit Advanced PDF Editor To remove this notice, visit: 14 www.foxitsoftware.com/shopping CHAPTER II SIHR OR BLACK MAGIC AND IT’S ORIGINAL HISTORY A. Definition Of Sihr The idea of sorcery, magic and witchcraft is present in most religions as it was part of the classical worldview whereby many workings of nature were unknown and understood as ruled by supernatural forces. The ‘blowing on knots’ which the above verse refers to is “a magical practice much in use in Semitic circles It was particularly popular in Jewish circles, despite its rigid prohibition in the Pentateuch. An allusion to this practice is found in the Sumerian Macila (The Burnt Tablets), where we read: “His knot is open, his witchcraft has been cancelled, and his spells now fill the desert.” The blowing itself, the bad breath and the spit, are considered an enemy’s curse.16 Magic or sorcery is an attempt to understand, experience and influence the world using rituals, symbols, actions, gestures and language17 The Arabic word translated in this passage as “magic” is sihr. The etymological meaning of sihr suggests that “it is the turning . of a thing from its true nature . or form . to something else which is unreal or a mere appearance “ (107) Arabic or Islamic magic is particularly prevalent, and it affects not just moslems. It’s known as “SIHR” in Islamic term. The word Sihr or Magicis derivedfrom the wordsahara-yasharu-sihran,fromformingthe original word, which issihrmeansdeceiving, bewitchinganddeceit. As for as 16Gabriel Mandel Khan, Magic’ in Encyclopeadia of the Qur’an, volume 3 (2003), p.248.) 17Hutton RonaldPagan Religions of the Ancient British Isles.