202 Italians New Towns As an Experimental Territory For

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ministero Dell'istruzione, Dell'universita' E Della Ricerca

MINISTERO DELL'ISTRUZIONE, DELL'UNIVERSITA' E DELLA RICERCA UFFICIO SCOLASTICO REGIONALE PER IL LAZIO ELENCO BENEFICIARI SECONDA POSIZIONE ECONOMICA PROVINCIA LATINA PROFILO ASSISTENTE AMMINISTRATIVO 0001) AGRESTI LORETTA NATA IL 13/02/1959 A EE CODICE FISCALE: GRSLTT59B53Z404J SEDE DI TITOLARITA': LTEE04500C CD FORMIA 2 COMUNE DI : FORMIA DECORRENZA DEL BENEFICIO ECONOMICO : 01/09/2009 0002) ALBANESE ANNA NATA IL 23/06/1964 A MINTURNO CODICE FISCALE: LBNNNA64H63F224Y SEDE DI TITOLARITA': LTIC803008 IC CARDUCCI COMUNE DI : GAETA DECORRENZA DEL BENEFICIO ECONOMICO : 01/09/2009 0003) ALBANO CIVITA NATA IL 21/08/1964 A FORMIA CODICE FISCALE: LBNCVT64M61D708I SEDE DI TITOLARITA': LTEE04300R CD FORMIA 1 COMUNE DI : FORMIA DECORRENZA DEL BENEFICIO ECONOMICO : 01/09/2009 0004) AMARENA FILOMENA NATA IL 26/06/1970 A SESSA AURUNCA CODICE FISCALE: MRNFMN70H66I676J SEDE DI TITOLARITA': LTIC82900C I.C. CENTRO STORICO TERRACINA COMUNE DI : TERRACINA DECORRENZA DEL BENEFICIO ECONOMICO : 01/09/2009 0005) ANASTASIO PIETRO NATO IL 03/07/1956 A SPERLONGA CODICE FISCALE: NSTPTR56L03I892N SEDE DI TITOLARITA': LTIC820002 L.DA VINCI DI S.FELICE CIRCEO COMUNE DI : SAN FELICE CIRCEO DECORRENZA DEL BENEFICIO ECONOMICO : 01/09/2009 0006) ANDREONE ERSILIA NATA IL 11/05/1971 A NAPOLI CODICE FISCALE: NDRRSL71E51F839V SEDE DI TITOLARITA': LTEE020004 APRILIA 1 COMUNE DI : APRILIA DECORRENZA DEL BENEFICIO ECONOMICO : 01/09/2009 PAG. 1 MINISTERO DELL'ISTRUZIONE, DELL'UNIVERSITA' E DELLA RICERCA UFFICIO SCOLASTICO REGIONALE PER IL LAZIO 0007) ANDREONE PATRIZIA NATA IL -

Modernism Without Modernity: the Rise of Modernist Architecture in Mexico, Brazil, and Argentina, 1890-1940 Mauro F

University of Pennsylvania ScholarlyCommons Management Papers Wharton Faculty Research 6-2004 Modernism Without Modernity: The Rise of Modernist Architecture in Mexico, Brazil, and Argentina, 1890-1940 Mauro F. Guillen University of Pennsylvania Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.upenn.edu/mgmt_papers Part of the Architectural History and Criticism Commons, and the Management Sciences and Quantitative Methods Commons Recommended Citation Guillen, M. F. (2004). Modernism Without Modernity: The Rise of Modernist Architecture in Mexico, Brazil, and Argentina, 1890-1940. Latin American Research Review, 39 (2), 6-34. http://dx.doi.org/10.1353/lar.2004.0032 This paper is posted at ScholarlyCommons. https://repository.upenn.edu/mgmt_papers/279 For more information, please contact [email protected]. Modernism Without Modernity: The Rise of Modernist Architecture in Mexico, Brazil, and Argentina, 1890-1940 Abstract : Why did machine-age modernist architecture diffuse to Latin America so quickly after its rise in Continental Europe during the 1910s and 1920s? Why was it a more successful movement in relatively backward Brazil and Mexico than in more affluent and industrialized Argentina? After reviewing the historical development of architectural modernism in these three countries, several explanations are tested against the comparative evidence. Standards of living, industrialization, sociopolitical upheaval, and the absence of working-class consumerism are found to be limited as explanations. As in Europe, Modernism -

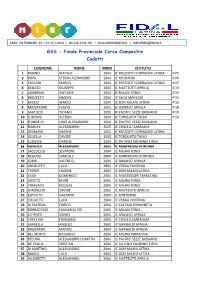

GSS Campestre

sede: via Botticelli, 35 – 04100 Latina - tel. 338-2485.356 – www.atleticalatina.it - [email protected] GSS - Finale Provinciale Corsa Campestre Cadetti COGNOME NOME ANNO ISTITUTO 32 1 PAIANO MATTEO 2004 IC FREZZOTTI CORRADINI LATINA 4'05 81 2 POPA STEFAN ALEXANDRU 2004 IC MS BIAGIO 4'06 31 3 CECCONI MARCO 2004 IC FREZZOTTI CORRADINI LATINA 4'07 58 4 DEDATO GIUSEPPE 2004 IC MATTEOTTI APRILIA 4'13 61 5 LAMBRAIA RAFFAELE 2004 IC MILANI FONDI 4'14 3 6 BROZZETTI SIMONE 2004 IC ALDO MANUZIO 4'15 26 7 MISSIO MARCO 2004 IC DON MILANI LATINA 4'16 50 8 MAZZAFERRI FLAVIO 2005 IC GRAMSCI APRILIA 4'18 90 9 SANTUCCI TIZIANO 2005 IC PACIFICI SEZZE BASSIANO 4'19 99 10 LUDOVISI ALESSIO 2004 IC TORQUATO TASSO 4'19 87 11 D'ANGELO LUIGI ALESSANDRO 2004 IC PACIFICI SEZZE BASSIANO 16 12 BIANCHI ALESSANDRO 2005 IC CENCELLI SABAUDIA 34 13 ZIMBARDI SIMONE 2004 IC FREZZOTTI CORRADINI LATINA 98 14 GUSELLA DAVIDE 2005 IC TORQUATO TASSO 21 15 LUDOVISI DANIELE 2004 IC DA VINCI SONNINO E RDV 51 16 ADINOLFI ALESSANDRO 2005 IC MANFREDINI PONTINIA 63 17 SACCOCCIO SLVATORE 2004 IC MILANI FONDI 53 18 NEGOSSI SAMUELE 2004 IC MANFREDINI PONTINIA 49 19 LORIA VALERTIO 2004 IC GRAMSCI APRILIA 101 20 ANGELOTTI LUCA 2004 IC VERGA PONTINIA 29 21 TRIPEPI SIMONE 2004 IC DON MILANI LATINA 76 22 STASI DOMENICO 2004 IC MONTESSORI TERRACINA 62 23 ORVETO KEVIN 2005 IC MILANI FONDI 65 24 STRAVATO NICOLAS 2004 IC MILANI FONDI 60 25 SPADACCIA DAVIDE 2005 IC MATTEOTTI APRILIA 72 26 ESPOSITO GAETANO 2004 IC MINTURNO 103 27 COLAUTTI LUCA 2004 IC VERGA PONTINIA 12 28 DI PASTENA ENRICO 2004 -

Territorio E Popolazione La Provincia Di Latina Si Estende Per 2.250 Kmq, È Costituita Da 33 Comuni E Una Popolazione Residen

Territorio e popolazione La provincia di Latina si estende per 2.250 kmq, è costituita da 33 comuni e una popolazione residente di 569.664 abitanti (Maschi 280.314 e Femmine 289.350), di cui 42.821 stranieri (Fonte Dati ISTAT al 31 dicembre 2013) Il territorio, diviso tra aree collinari, montuose e piane costiere comprende anche le isole dell’arcipelago pontino. Il 67% della popolazione risiede in pianura, il 32% in collina e l’1% circa in montagna e nelle isole dell’arcipelago pontino. La densità abitativa della provincia di Latina è di 245 abitanti/kmq con una variabilità di 722 abitanti/kmq nel comune di Gaeta e di 17 abitanti/kmq nel comune di Campodimele. La provincia di Latina si caratterizza per una popolazione giovane con un’età media di 42,7 anni e un indice di vecchiaia (i.v.) pari a 133 il più basso del Lazio. Seppur più lento rispetto alle altre province laziali, è comunque emergente il progressivo invecchiamento della popolazione dovuto alla diminuzione del tasso di natalità e al contemporaneo aumento della sopravvivenza e speranza di vita. Dall’analisi degli indicatori di struttura della popolazione per zone altimetriche emerge che le classi d’età più giovani dai 15 ai 64 anni prevalgono in pianura e in collina. In montagna e nelle isole prevale la popolazione di età superiore ai 65 anni.Il territorio dell’Azienda Unità Sanitaria Locale di Latina è organizzato in 5 Distretti Sanitari. Il Distretto 1 si caratterizza per un territorio prevalentemente pianeggiante, una popolazione giovane e un’ elevata presenza di stranieri, che nel comune di Aprilia raggiunge l’11,2% della popolazione. -

COMUNE DI SABAUDIA Provincia Di Latina

fasc MPI - AVVISO appalto aggiudicato COMUNE DI SABAUDIA Provincia di Latina AREA 3 – AFFARI TECNICI DEL TERRITORIO – SETTORE 3.2 – LAVORI PUBBLICI SERVIZIO PROGRAMMAZIONE APPALTI AVVISO RELATIVO AD APPALTO AGGIUDICATO (Artt.65 e 122 comma 7 del D.Lgs. 163/2006) OGGETTO: PROCEDURA DI GARA PER L’AFFIDAMENTO DI SERVIZI DI “MANUTENZIONE IMPIANTO DI PUBBLICA ILLUMINAZIONE” – CIG: 6267138DDF. COMUNE DI SABAUDIA – C.F. 80004190593 – Area Tecnica Settore Lavori Pubblici – Piazza del Comune, 1 – 04016 Sabaudia (LT). PROCEDURA DI AGGIUDICAZIONE PRESCELTA E MOTIVAZIONE: procedura negoziata mediante cottimo fiduciario ai sensi dei commi 9 ed 11 dell’art. 125 del D.Lgs. 12/04/2006 n.163 per le motivazioni di cui alla determinazione a contrarre n. 95 del 25/05/2015. OGGETTO – natura e entità delle prestazioni “Servizio di manutenzione impianto di pubblica illuminazione”, l’appalto rientra nella tipologia di cui all’art. 21 del D.Lgs. 163/2006 in quanto prestazione compresa nei servizi di manutenzione di pubblica illuminazione, servizi riconducibili alla categoria “1” dell’Allegato “IIA” del Codice e sono individuati all’interno del vocabolario comune degli appalti pubblici (CPV) con i seguenti codici: 50232100-1 e 50232000-0 – valore stimato dell’appalto €. 90.000,00. DATA DI AGGIUDICAZIONE DELL'APPALTO: 30 Giugno 2015 aggiudicazione definitiva disposta con Determinazione Dirigenziale n. 125/LL.PP. - Con Determinazione Dirigenziale n° 139/LL.PP. del 04/08/2015 veniva dichiarata l'efficacia dell'aggiudicazione definitiva. CRITERIO DELL'AGGIUDICAZIONE DELL'APPALTO: massimo ribasso percentuale sul canone annuo. INDICAZIONE DEI SOGGETTI INVITATI E NUMERO DI OFFERTE RICEVUTE: 1 Pontina Scavi srl Via dei Sicani, 2 - 04100 Latina 2 Stagno Impresit di Vito Carolina Via Trifolle, 6 - 03040 Ausonia (FR) 3 M. -

RESOCONTO NOMINE COLL. SCOLASTICI Ex LSU

RESOCONTO NOMINE COLL. SCOLASTICI ex LSU LTIC82100T I.C. “GRAMSCI” Aprilia 1 Giovanni Lombardo 2 Luciana Marzullo 3 Maria Antonietta Testa 4 Anna D’Ambrosi LTIC82200N I.C. “PASCOLI” Aprilia 1 Silvana Raponi 2 Antonella Galante 3 Annarita Pallottini 4 Selma Yazidi Ep Ouannes LTIC824009 I.C. “Matteotti” Aprilia 1 Silvana Zagaroli 2 Daniela Vaglianti 3 Maria Caporasi 4 LTIC83100C I.C. “Zona Leda” Aprilia 1 Maria Ciccone 2 Gioconda Raponi 3 4 LTIC83700B I.C. “Garibaldi” Aprilia 1 Emanuela Suppa 2 Margaret Asuquo Ubaha 3 Maria Luisa Soccorsi 4 Mirella Scarsella 5 Silvana Drago LTIS84400E I.C. “Toscanini” Aprilia 1 Cinzia Spina 2 Clementina Rutilo 3 Sara Guerra 4 Ana Griselda Granados Martines 5 Rita Ferruzzi 6 Marzia memè LTIS004008 I.S. “Rosselli” Aprilia 1 Anna Giacomi 2 3 4 5 LTPS060002 Liceo “Meucci” Aprilia 1 Mariangela Carè 2 Filomena Amato 3 Daniela Sanzone 4 5 LTTD100003 ITC “Tallini” Castelforte 1 Milena La Starza 2 Carla D’Alessandro LTIC80000R I.C. “Caetani” Cisterna 1 Maria Teresa Caetani 2 Rosa Maria Silvia 3 Daniela Forti 4 5 LTIC838007 I.C. “Volpi” Cisterna 1 Tiziana Pietrosanti 2 Maria Zamuner 3 Gina Giovannoni 4 Carla Purezza LTIC839003 I.C. “Plinio” Cisterna 1 Rosanna Scioni 2 Francesca Martellini 3 Alessia Mancini 4 Francesca Mancini LTIS00100R Campus dei Licei “Ramadù” 1 2 3 4 LTIC83400X I.C. “Chiominto” Cori 1 Paola Pasquali 2 Anna Maria Siracusa 3 4 LTIS026005 I.S. “De Libero-Gobetti” Fondi 1 Sergio Vitale 2 Benedetto Leone 3 4 LTIC812003 I.C. “Mattej” Formia 1 2 3 4 5 LTIS00700Q I.S. -

Partenze Da Latina

Orario in vigore dal 07 Jan 2016 al 28 Feb 2016 pag. 1/48 Partenze Da Latina Staz.FS, Latina Scalo FS DESTINAZIONE LUN-VEN SABATO FESTIVO per Bassiano p.zza G.Matteotti 04:591..05:171..05:521..06:371..07:021..08:101.. 04:591..05:171..06:001..06:451.. 12:111..14:361..15:061..17:281..18:381..20:311.. 07:101..08:151..12:151..14:401.. 17:281..18:401..20:351.. 1. Latina Fs Bv - Stabilimento Mistral - Doganella Bv per Norma Ninfa Ninfa 17:481.. 17:501.. 1. Latina Fs Bv - Stabilimento Mistral - Doganella Bv - Doganella Norma p.zza Roma 05:421..07:351..13:111..13:561..14:361..15:111.. 05:421..07:351..13:111..14:001.. 16:221..17:482..18:481..20:361.. 16:211..17:502..20:051.. 1. Latina Fs Bv - Stabilimento Mistral - Doganella Bv 2. Latina Fs Bv - Stabilimento Mistral - Doganella Bv - Doganella - Ninfa Gli orari in grassetto (ad es: 07.00) indicano le partenze da Capolinea. Gli orari di transito (ad es: 07.00), essendo soggetti alla variabilità del traffico ed essendo non previsti slarghi per l'attesa, possono subire variazioni anche in anticipo. E' pertanto opportuno anticipare l'attesa alla fermata. Servizio Sistemi Informativi Sistemi di Supporto all'Esercizio Stampato il 07/01/2016 Orario in vigore dal 07 Jan 2016 al 28 Feb 2016 pag. 2/48 per Sermoneta via Sermonetana 08:201..12:361.. 08:251..12:401.. 1. Latina Fs Bv - Murillo - Monticchio - Casal Dei Papi Gli orari in grassetto (ad es: 07.00) indicano le partenze da Capolinea. -

1. Picardi Sharon Roma (Rm) 161349 2. Picascia Laura San Felice Circeo (Lt) 153601 3

cciaa_lt AOO1-CCIAA_LT - REG. CLTRP - PROTOCOLLO 0003918/U DEL 08/03/2018 12:08:14 DPR 23 luglio 2004, n.247 (Art.2, c.1, lett. c ) - Avvio del procedimento di cancellazione dei seguenti imprenditori: Cognome e Nome Comune Sede Numero REA 1. PICARDI SHARON ROMA (RM) 161349 2. PICASCIA LAURA SAN FELICE CIRCEO (LT) 153601 3. PICCA CARMINE SEZZE (LT) 182865 4. PICCOLO MAURIZIO SORA (FR) 153455 5. PIETRICOLA DANILO PONTINIA (LT) 127701 6. PIETROSANTI GLORIA SERMONETA (LT) 162094 7. PIETROVANNI STEFANIA TERRACINA (LT) 161383 8. PIROTTI GIULIANO SEZZE (LT) 127706 9. PISA MARIO SEZZE (LT) 119557 10. PISTILLI CARLO CORI (LT) 155087 11. PIZZUTI FRANCESCO SABAUDIA (LT) 71606 12. POLIZZI BEATRICE ROMA (RM) 166021 13. POMPEI SABRINA ARDEA (RM) 158327 14. POMPONI MARCO APRILIA (LT) 177946 15. PONTECORVI GIGLIOLA TERRACINA (LT) 160566 16. PREVIATI PAOLA PONTINIA (LT) 139739 17. PRICE JUDITH SUSAN CISTERNA DI LATINA 159300 18. PROIA MARIA LATINA (LT) 127142 19. PULITA CARLO LATINA (LT) 180395 20. QUADROTTO VALENTINA LATINA (LT) 178897 21. QUISPE LANDA NELSON APRILIA (LT) 161300 GEOVANNY 22. RADULESCU MARIA DENISA APRILIA (LT) 175701 23. RAGONESE MARCO LATINA (LT) 130587 24. RANUCCI ENRICO LATINA (LT) 130603 25. RAPONE CRISTIAN LATINA (LT) 173082 26. RIZZI STEFANO TERRACINA (LT) 104939 27. RIZZI GERARDO LATINA (LT) 136478 28. ROMA FEDERICA APRILIA (LT) 165872 29. ROMAGNOLI MARIOLINA GABICCE MARE (PU) 179455 30. ROMANO MARIO MINTURNO (LT) 147059 31. ROSSI CLAUDIO PRIVERNO (LT) 173374 32. ROSSI VINCENZO TERRACINA (LT) 148178 33. RUSSO VINCENZO FONDI (LT) 178928 34. SACCO FRANCESCO APRILIA (LT) 164603 35. SADOCCO IDELMO LATINA (LT) 159243 36. -

Marshes, Mosquitos and Mussolini

Federico Caprotti. Mussolini's Cities: Internal Colonialism in Italy, 1930-1939. Youngstown: Cambria Press, 2007. xxvi + 290 pp. $84.95, cloth, ISBN 978-1-934043-53-0. Reviewed by Joshua W. Arthurs Published on H-Italy (December, 2007) In his speech inaugurating the newly con‐ state control in Mussolini's Italy. Indeed, the structed town of Littoria in 1932, Benito Mussolini strongest aspects of the book are those in which famously announced that "this is the war we pre‐ the author retains a foothold on the dry land of fer." The battle in question was the reclamation of human geography and development. For example, the malarial marshland around Rome (the Agro he suggests that the Pontine Marshes should be Pontino), heralded at home and abroad as evi‐ seen as a sociocultural landscape, a hybrid space dence of Fascism's dynamic program of modern‐ reflecting the dialectic between rurality and ur‐ ization. To this day the New Towns--Littoria (now banity at the core of the Fascist project. The Latina), Sabaudia, Pontinia, Aprilia and Pomezia, regime attempted to resolve this conflict by distin‐ all built between 1932 and 1939--stand as tangible guishing between an untamed, unhealthy and un‐ reminders of the regime's desire to reclaim, re‐ productive "first nature" and a "desirable nature generate and redeem the Italian landscape and ... where nature was socially co-opted and chan‐ population. neled towards a particular socially-engineered ex‐ In Mussolini's Cities: Internal Colonialism in istence ... " (p. 63). His geography background is Italy, 1930-1939, Federico Caprotti seeks to write also helpful in explaining some of the technical not so much a "linear history" of this "battle" as an aspects of bonifica integrale (land reclamation), as account of "the lived landscape and multiple so‐ when he discusses the various chemicals used to cial, ideological and technological discourses combat malaria-bearing mosquitoes or the "tech‐ which contributed to the making of this amazing nological support network" built "to sustain and landscape" (p. -

Arpinoand Surroundings

THE QUINTESSENCE OF ITALY ARPINO and surroundings through the eyes of ALFANO REAL ESTATE FOR MORE INFO ABOUT ITALIAN PROPERTIES CLICK ON WWW.GATE-AWAY.COM DID YOU KNOW ARPINO? Probably you have never heard of Arpino, but many overseas house-hunters already have… and some of them already own their piece of la dolce vita there. The interest of international would-be buyers in Italy is now always more focused on off-the-beaten-track destinations like Arpino in Ciociaria area of Lazio region − which mainly coincides with Frosinone province − and not only on the most famous locations like Florence, Venice and Rome just to name a few. It’s a must if… 1 YOU ARE LOOKING FOR AMAZING AFFORDABLE PROPERTIES You can find beautiful housing solutions at very affordable prices. Here are indicative average prices: House to be restored – from € 350 to € 550 / m² House ready to be lived in – from € 700 to € 1,100 / m² Brand new house – from € 1,200 to € 1,500 / m² But oh yes, if you are searching for a luxury home you’ll be literally spoiled for choice, especially if you like the idea of living in an elegant historic palazzo. 2 YOU WANT TO BE CLOSE TO A MAJOR AIRPORT Usually they have a higher number of routes as well as low-cost airlines. Arpino it's just 1.5 from either Naples or Rome airports. YOU LOVE THE BEACH BUT WANT TO LIVE FAR FROM 3 THE HUSTLE AND BUSTLE OF SEA RESORTS ... and because properties in coastal towns are more expensive than those situated inland. -

Lista Soggetti

Pag.: 1 di 59 UFFICIO PROVINCIALE DI LATINA Catasto Terreni - Comune di CISTERNA DI LATINA AVVISO DI DEPOSITO DI ATTI NELLA CASA COMUNALE Attribuzione di rendita catastale presunta ai fabbricati non dichiarati in catasto, liquidazione di oneri e irrogazione sanzioni (Art. 5 bis Legge 26 febbraio 2011, n. 10). ELENCO SOGGETTI INTESTATARI Si avverte che nella Casa Comunale sono stati depositati gli atti qui di seguito descritti Cognome Nome / Denominazione Comune nascita / Sede legale Data nascita Comune Sez. Foglio Numero Sub. Protocollo avviso ABAGNALE FORTUNA SANT`ANTONIO ABATE 29/06/1943 C740 161 705 LT0061670 2012 001 ABATECOLA MARIA CIVITA FALVATERRA 01/01/1952 C740 170 316 LT0061937 2012 001 ABBRUZZESE ANTONIO NAPOLI 14/04/1937 C740 161 918 LT0061915 2012 001 ACCETTOLA ENZO CASTELLIRI 14/03/1961 C740 169 98 LT0060917 2012 001 ACCURSO MARGHERITA LINDA TUNISIA 17/09/1960 C740 145 103 LT0061526 2012 001 AGOSTI LAURA CISTERNA DI LATINA 30/09/1960 C740 4 128 LT0060541 2012 001 AGOSTINI NATALE CISTERNA DI LATINA 25/12/1930 C740 4 994 LT0057895 2012 001 AIELLI FERNANDA LATINA 18/07/1944 C740 161 384 LT0061046 2012 001 ALBANESE FRANCESCA BAGNARA CALABRA 02/03/1933 C740 177 36 LT0061337 2012 001 ALTRINI ERSILIA VELLETRI 22/01/1951 C740 158 228 LT0061711 2012 001 AMODIO INES SALERNO 09/11/1941 C740 46 148 LT0060934 2012 001 AMORI ANNUNZIATA ROMA 20/05/1946 C740 149 461 LT0060905 2012 001 ANCONA CATERINA LIBIA 22/10/1961 C740 141 47 LT0061630 2012 001 ANDREANI AUGUSTO ROMA 01/10/1920 C740 46 368 LT0060939 2012 001 ANDREANI AUGUSTO ROMA 01/10/1920 -

Comune Telefono Responsabile Richiesta a Mezzo Indirizzo a Cui

Richiesta Comune Telefono Responsabile a mezzo Indirizzo a cui richiedere Note sui pagamenti Sito comune Aprilia 06 928641 Giannini Rocco PEC [email protected] certificati esenti per istituzioni www.comune.aprilia.lt.it Bassiano 773355226 Sig.ra Pinti PEC [email protected] tramite busta con francobollo www.comune.bassiano.lt.it Campodimele 0771 598013 Sepe Laura PEC [email protected] certificati esenti per istituzioni www.comune.campodimele.lt.it Castelforte 0771 60791 Ciorra Cesare PEC [email protected] certificati esenti per istituzioni www.comune.castelforte.lt.it Cisterna di Latina 06 968341 De Vincenti Luca PEC [email protected] certificati esenti per istituzioni www.comune.cisterna-di-latina.latina.it Cori 06 966171 Calicchia Federica PEC [email protected] certificati esenti per istituzioni www.comune.cori.lt.it Fondi 0771 5071 Toscano Luca PEC [email protected] tramite PagoPa www.comunedifondi.it Formia 0771 7781 Di Nitto Alessandra PEC [email protected] certificati esenti per istituzioni www.comune.formia.lt.it Gaeta 0771 4691 Marra Antonella PEC [email protected] certificati esenti per istituzioni www.comune.gaeta.lt.it Itri 0771 7321 Manzo Andrea PEC [email protected] certificati esenti per istituzioni www.comune.itri.lt.it LATINA 0773 6521 Ventriglia Daniela PEC [email protected] certificati esenti per istituzioni www.comune.latina.it Lenola