Irish Progenitors of Texas

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Stephen F. Austin and the Empresarios

169 11/18/02 9:24 AM Page 174 Stephen F. Austin Why It Matters Now 2 Stephen F. Austin’s colony laid the foundation for thousands of people and the Empresarios to later move to Texas. TERMS & NAMES OBJECTIVES MAIN IDEA Moses Austin, petition, 1. Identify the contributions of Moses Anglo American colonization of Stephen F. Austin, Austin to the colonization of Texas. Texas began when Stephen F. Austin land title, San Felipe de 2. Identify the contributions of Stephen F. was given permission to establish Austin, Green DeWitt Austin to the colonization of Texas. a colony of 300 American families 3. Explain the major change that took on Texas soil. Soon other colonists place in Texas during 1821. followed Austin’s lead, and Texas’s population expanded rapidly. WHAT Would You Do? Stephen F. Austin gave up his home and his career to fulfill Write your response his father’s dream of establishing a colony in Texas. to Interact with History Imagine that a loved one has asked you to leave in your Texas Notebook. your current life behind to go to a foreign country to carry out his or her wishes. Would you drop everything and leave, Stephen F. Austin’s hatchet or would you try to talk the person into staying here? Moses Austin Begins Colonization in Texas Moses Austin was born in Connecticut in 1761. During his business dealings, he developed a keen interest in lead mining. After learning of George Morgan’s colony in what is now Missouri, Austin moved there to operate a lead mine. -

Guadalupe, San Antonio, Mission, and Aransas Rivers and Mission, Copano, Aransas, and San Antonio Bays Basin and Bay Area Stakeholders Committee

Guadalupe, San Antonio, Mission, and Aransas Rivers and Mission, Copano, Aransas, and San Antonio Bays Basin and Bay Area Stakeholders Committee May 25, 2012 Guadalupe, San Antonio, Mission, & Aransas Rivers and Mission, Copano, Aransas, & San Antonio Bays Basin & Bay Area Stakeholders Committee (GSA BBASC) Work Plan for Adaptive Management Preliminary Scopes of Work May 25, 2012 May 10, 2012 The Honorable Troy Fraser, Co-Presiding Officer The Honorable Allan Ritter, Co-Presiding Officer Environmental Flows Advisory Group (EFAG) Mr. Zak Covar, Executive Director Texas Commission on Environmental Quality (TCEQ) Dear Chairman Fraser, Chairman Ritter and Mr. Covar: Please accept this submittal of the Work Plan for Adaptive Management (Work Plan) from the Guadalupe, San Antonio, Mission, and Aransas Rivers and Mission, Copano, Aransas and San Antonio Bays Basin and Bay Area Stakeholders Committee (BBASC). The BBASC has offered a comprehensive list of study efforts and activities that will provide additional information for future environmental flow rulemaking as well as expand knowledge on the ecosystems of the rivers and bays within our basin. The BBASC Work Plan is prioritized in three tiers, with the Tier 1 recommendations listed in specific priority order. Study efforts and activities listed in Tier 2 are presented as a higher priority than those items listed in Tier 3; however, within the two tiers the efforts are not prioritized. The BBASC preferred to present prioritization in this manner to highlight the studies and activities it identified as most important in the immediate term without discouraging potential sponsoring or funding entities interested in advancing efforts within the other tiers. -

Stormwater Management Program 2013-2018 Appendix A

Appendix A 2012 Texas Integrated Report - Texas 303(d) List (Category 5) 2012 Texas Integrated Report - Texas 303(d) List (Category 5) As required under Sections 303(d) and 304(a) of the federal Clean Water Act, this list identifies the water bodies in or bordering Texas for which effluent limitations are not stringent enough to implement water quality standards, and for which the associated pollutants are suitable for measurement by maximum daily load. In addition, the TCEQ also develops a schedule identifying Total Maximum Daily Loads (TMDLs) that will be initiated in the next two years for priority impaired waters. Issuance of permits to discharge into 303(d)-listed water bodies is described in the TCEQ regulatory guidance document Procedures to Implement the Texas Surface Water Quality Standards (January 2003, RG-194). Impairments are limited to the geographic area described by the Assessment Unit and identified with a six or seven-digit AU_ID. A TMDL for each impaired parameter will be developed to allocate pollutant loads from contributing sources that affect the parameter of concern in each Assessment Unit. The TMDL will be identified and counted using a six or seven-digit AU_ID. Water Quality permits that are issued before a TMDL is approved will not increase pollutant loading that would contribute to the impairment identified for the Assessment Unit. Explanation of Column Headings SegID and Name: The unique identifier (SegID), segment name, and location of the water body. The SegID may be one of two types of numbers. The first type is a classified segment number (4 digits, e.g., 0218), as defined in Appendix A of the Texas Surface Water Quality Standards (TSWQS). -

Stephen F. Austin Books

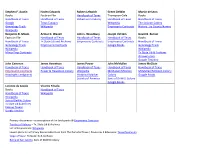

Stephen F. Austin Haden Edwards Robert Leftwich Green DeWitt Martin de Leon Books Facts on File Handbook of Texas Thompson-Gale Books Handbook of Texas Handbook of Texas Robertson’s Colony Handbook of Texas Handbook of Texas Google Texas Escapes Wikipedia The DeLeon Colony Genealogy Trails Wikipedia Empresario Contracts History…by County Names Wikipedia Benjamin R. Milam Arthur G. Wavell John L. Woodbury Joseph Vehlein David G. Burnet Facts on File Handbook of Texas Handbook of Texas Handbook of Texas Books Handbook of Texas Tx State Lib and Archives Empresario Contracts Empresario Contracts Handbook of Texas Genealogy Trails Empresario Contracts Google Books Genealogy Trails Wikipedia Wikipedia Minor Emp Contracts Tx State Lib & Archives Answers.com Google Timeline John Cameron James Hewetson James Power John McMullen James McGloin Handbook of Texas Handbook of Texas Handbook of Texas Handbook of Texas Handbook of Texas Empresario Contracts Power & Hewetson Colony Wikipedia McMullen/McGloin McMullen/McGloin Colony Headright Landgrants Historical Marker Colony Google Books Society of America Sons of DeWitt Colony Google Books Lorenzo de Zavala Vicente Filisola Books Handbook of Texas Handbook of Texas Wikipedia Wikipedia Sons of DeWitt Colony Tx State Lib & Archives Famous Texans Google Timeline Primary documents – transcriptions of the land grants @ Empresario Contracts Treaties of Velasco – Tx. State Lib & Archives List of Empresarios: Wikipedia Lesson plans for a Primary Source Adventure from The Portal of Texas / Resources 4 Educators: Texas Revolution Siege of Bexar: Tx State Lib & Archives Battle of San Jacinto: Sons of DeWitt Colony . -

Watershed and Flow Impacts on the Mission-Aransas Estuary

Watershed and Flow Impacts on the Mission- Aransas Estuary Sarah Douglas GIS in Water Resources Fall 2016 Introduction Background Estuaries are vibrant and dynamic habitats occurring within the mixing zone of fresh and salt water. They are home to species often capable of surviving in a variety of salinities and other environmental stressors, and are often highly productive due to the high amount of nutrient input from both terrestrial and marine sources. As droughts become more common in certain areas due to climate change, understanding how species adapt, expand, or die is crucial for management strategies (Baptista et al 2010). Salinity can fluctuate wildly in back bays with limited rates of tidal exchange with the ocean and low river input, leading to changes in ecosystem structure and function (Yando et al 2016). The recent drought in Texas from 2010 to 2015 provides a chance to study the impacts of drought and river input on an estuarine system. While some studies have shown that climate changes are more impactful on Texas estuaries than changes in watershed land use (Castillo et al 2013), characterization of landcover in the watersheds leading to estuaries are important for a variety of reasons. Dissolved organic carbon and particulate organic matter influx is an important driver of microbial growth in estuaries (Miller and Shank 2012), and while DOC and POM can be generated in marine systems, terrestrial sources are also significant. Study Site The site chosen for this project is the Mission-Aransas estuary, located within the Mission-Aransas National Estuarine Research Reserve (NERR). In addition to being an ideal model of a Gulf Coast barrier island estuary, the Mission-Aransas NERR continuously monitors water parameters, weather, and nutrient data at a series of stations located within the back bays and ship channel. -

Italian and Irish Contributions to the Texas War for Independence

East Texas Historical Journal Volume 23 Issue 2 Article 7 10-1985 Italian and Irish Contributions to the Texas War for Independence Valentine J. Belfiglio Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.sfasu.edu/ethj Part of the United States History Commons Tell us how this article helped you. Recommended Citation Belfiglio, alentineV J. (1985) "Italian and Irish Contributions to the Texas War for Independence," East Texas Historical Journal: Vol. 23 : Iss. 2 , Article 7. Available at: https://scholarworks.sfasu.edu/ethj/vol23/iss2/7 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the History at SFA ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in East Texas Historical Journal by an authorized editor of SFA ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. 28 EAST TEXAS mSTORICAL ASSOCIATION ITALIAN AND IRISH CONTRIBUTIONS TO THE TEXAS WAR FOR INDEPENDENCE by Valentine J. Belfiglio The Texas War for Independence erupted with the Battle of Gon zales on October 2, 1835.' Centralist forces had renounced the Mex ican constitution and established a dictatorship. The Texas settlers, meanwhile, developed grievances. They desired to retain their English language and American traditions, and feared that the Mex ican government would abolish slavery. Texans also resented Mex ican laws which imposed duties on imported goods, suspended land contracts, and prohibited American immigration. At first the Americans were bent on restoring the constitution, but later they decided to fight for separation from Mexico. Except for research by Luciano G. Rusich (1979, 1982), about the role of the Marquis of " Sant'Angelo, and research by John B. -

1836 CONSTITUTION of the REPUBLIC of TEXAS AS AMENDED Page 1 of 13 Sec

CONSTITUTION OF THE R E P U B L I C O F T E X A S _________ As amended the third day in September, in the year of our Lord two thousand and seven: As Referenced * We, the people of Texas, in order to form a government, establish justice, ensure domestic tranquility, provide for the common defence and general welfare; and to secure the blessings of liberty to ourselves, and our posterity, do ordain and establish this constitution. ARTICLE I. Section 1. The powers of this government shall be divided into three departments, viz: legislative, executive and judicial, which shall remain forever separate and distinct. Sec. 2. The legislative power shall be vested in a senate and house of representatives, to be styled the Congress of the republic of Texas. Sec. 3. The members of the house of representatives shall be chosen annually, on the first Monday of September each year, until congress shall otherwise provide by law, and shall hold their offices one year from the date of their election. Sec. 4. No person shall be eligible to a seat in the house of representatives until he shall have attained the age of twenty-five years, shall be a citizen of the republic, and shall have resided in the county or district six months next preceding his election. Sec. 5. The house of representatives shall not consist of less than twenty-four, nor more than forty members, until the population shall amount to one hundred thousand souls, after which time the whole number of representatives shall not be less than forty, nor more than one hundred: Provided, however, that each county shall be entitled to at least one representative. -

Mexican Texas: Colonization Through Rebellion (Ch

Unit 3.2 Study Guide: Mexican Texas: Colonization Through Rebellion (Ch. 7) Expectations of the Student Identify the Spanish Colonial and Mexican National eras of Texas History and define its characteristics Apply chronology to the events of the eras above with years 1820, 1821, 1823, 1824, 1825 Identify the individuals, issues, and events related to Mexico becoming an independent nation and its impact on Texas, including Texas involvement in the fight for independence, the Mexican Federal Constitution of 1824, the merger of Texas and Coahuila as a state, the State Colonization Law of 1825, and slavery Identify the contributions of significant individuals, including Moses Austin, Stephen F. Austin, Erasmo Seguin, Mar- tin de Leon, and Green DeWitt, during the Mexican settlement of Texas Contrast Spanish, Mexican, and Anglo purposes for and methods of settlement in Texas Essential Questions: How did self-determination motivate Texans to move toward revolution? When is it necessary to seek change? Essential Topics of Significance Essential Vocabulary Advertising for Colonists Bastrop (town) Moses Austin Baron de Bastrop Mexican Independence Gonzales (town) Antonio Martinez Andrew Robinson 1821 San Patricio (town) Stephen F. Austin Jared Groce The “Old 300” Victoria (town) San Felipe de Austin Erasmo Seguin James Power and James Imperial Colonization Hewetson MX Constitution of 1824 Law Luciano Garcia John McMullen and Coahuila y Tejas Slaves and free African Martin de Leon Americans in TX James McGloin Saltillo Patricia de la Garza de Why Austin’s Colonies Mary Austin Holley State Colonization Law Leon Succeeded of 1825 Thomas J. Pilgrim Women’s roles and Augustin de Iturbide The “Little Colony” Frances Trask Education Green DeWitt Essential Vocabulary Dates to Remember Unit 3.2, Part 2 GPERSIA — due Wednesday, 10/29 colonization Federalist Ch. -

Mission Refugio Original Site Calhoun County, Texas

Mission Refugio Original Site Calhoun County, Texas Context When, at the close of the seventeenth century, the French and the Spaniards first attempted to occupy the Gulf coast near Matagorda Bay, that region was the home of a group of native tribes now called Karankawa. The principal tribes of the group were the Cujane, Karankawa, Guapite (or Coapite), Coco, and Copane. They were closely interrelated, and all apparently spoke dialects of the same language, which was different from that of their neighbors farther inland. The Karankawa dwelt most commonly along the coast to the east and the west of Matagorda Bay; the Coco on the mainland east of Matagorda Bay near the lower Colorado River: the Cujane and Guapite on either side of the bay, particularly to the west of it; and the Copane from the mouth of the Guadalupe River to around Copano Bay, to which the tribe has given its name1. Their total number was estimated at from four to five hundred fighting men. 1 The Spanish Missions in Texas comprise a series of religious outposts established by Spanish Catholic Dominicans, Jesuits, and Franciscans to spread the Christian doctrine among the local Native Americans, but with the added benefit of giving Spain a toehold in the frontier land. The missions introduced European livestock, fruits, vegetables, and industry into the Texas region. In addition to the presidio (fort) and pueblo (town), the misión was one of the three major agencies employed by the Spanish crown to extend its borders and consolidate its colonial territories. In all, twenty-six missions were maintained for different lengths of time within the future boundaries of the state. -

2008 Basin Summary Report San Antonio-Nueces Coastal Basin Nueces River Basin Nueces-Rio Grande Coastal Basin

2008 Basin Summary Report San Antonio-Nueces Coastal Basin Nueces River Basin Nueces-Rio Grande Coastal Basin August 2008 Prepared in cooperation with the Texas Commission on Environmental Quality Clean Rivers Program Table of Contents List of Acronyms ................................................................................................................................................... ii Executive Summary ............................................................................................................................................. 1 Significant Findings ......................................................................................................................................... 1 Recommendations .......................................................................................................................................... 4 1.0 Introduction ................................................................................................................................................... 5 2.0 Public Involvement ....................................................................................................................................... 6 Public Outreach .............................................................................................................................................. 6 3.0 Water Quality Reviews .................................................................................................................................. 8 3.1 Water Quality Terminology -

Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of MASTER of ARTS

/3 9 THE TEXAS REVOLUTION AS AN INTERNAL CONSPIRACY THESIS Presented to the Graduate Council of the North Texas State University in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of MASTER OF ARTS By Patsy Joyce Waller,. B. A. Denton, Texas June, 1965 PREFACE In the past many causes for the Texas Revolution of 1835 1836 have been suggested. Various politicians, such as John Quincy Adams, and such abolitionists as Benjamin Lundy and William Ellery Channing have charged that the struggle for independence represented a deliberate conspiracy on the part of vested economic groups in the United States--a plot on the part of southern slaveholders and northern land specula- tors to take over Texas in order to extend the slaveholding territory of the United States. Those who opposed President Andrew Jackson maintained that the Texas revolt was planned by Jackson in co-operation with Sam Houston for the purpose of obtaining Texas for the United States in order to bring into the Union a covey of slave states that would fortify and perpetuate slavery. The detailed studies of Eugene C. Barker, George L. Rives, William C. Binkley, and other historians have disproved these theories. No documentary evidence exists to show that the settlement of Texas or the Texas Revolution constituted any kind of conspiracy on the part of the United States, neither the government nor its inhabitants. The idea of the Texas Revolution as an internal con- spiracy cannot be eliminated. This thesis describes the role of a small minorit: of the wealthier settlers in Texas in iii precipitating the Texas Revolution for their own economic reasons. -

DRTN Ewsletter

Daughters of the Republic of Texas San Jacinto Chapter, Houston The San Jacinto Dispatch Eron Brimberry Tynes, President February 2008 Linda Beverlin, Editor President’s Message There is not a more appropriate observance of our Texas Independence than a group of Texians gathered together On February 12, 1836 Santa Anna crosses the Rio outdoors with our marvelous winter weather, eating Grande and heads north into Texas to reclaim the Alamo delicious food, listening to good music and enjoying the and end the rebellion. In Texas, revolution is in the air, our company of our friends. Please make a special effort to pioneer ancestors are preparing to defend Texas and fight join us this year, as we perpetuate the memory and spirit for Liberty and Independence. A Convention has been of the men and women who achieved and maintained the called at Washington-on-the-Brazos. Delegates are independence of Texas. planning to travel there and other men are contemplating whether to go to the Alamo, Goliad, or to join the Texian In the immortal words of Colonel William Barrett Travis, Army. The Texian Army will need arms, supplies and munitions. “I shall never surrender or retreat” “Victory or Death” The siege of the Alamo begins February 23 and Colonel William Travis will pen his famous letter on February 24, “ . To the people of Texas and all Americans in the world,” Travis writes . ” Then I call on you in the name of Liberty, of patriotism and everything dear to the American Eron Tynes, President character to come to our aid, with all dispatch, .