Mission Refugio Original Site Calhoun County, Texas

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Download PDF-1.7 MB File

Battles of the Texas Revolution: 1835 Campaign © Stephen L. Hardin, Ph.D., McMurry University Battle of Gonzales Date: October 2, 1835 Texian Force: 150 Texian Commander: John Henry Moore Centralist Force: 100 Centralist Commander: Francisco Castañeda Texian Casualties: 1 wounded Centralist Casualties: 2 killed Analysis: Opening engagement of the Texas Revolution, hence the “Lexington of Texas.” The Texians actually boasted two artillery pieces: the six-pound “Come-and-Take-It” cannon and another that Castañeda described as an “esmeril”—a diminutive gun firing a ball that weighed about ¼ of a pound. The esmeril remains on display at the Gonzales Memorial Museum. While more a skirmish than a battle, the engagement was nonetheless important as the spark that set off the powder keg. Shots were fired; blood was shed; the dye was cast. Battle of Gonzales: Location and Images Capture of the Presidio La Bahía (Goliad) Date: October 9, 1835 Texian Force: 125 Texian Commander: George Collinsworth Centralist Force: 50 Centralist Commander: Juan López Sandoval Texian Casualties: 1 wounded Centralist Casualties: 1 killed, 3 wounded Analysis: Centralist General Martín Perfecto de Cos stripped the garrison, leaving a skeleton force to defend the presidio. The small number was insufficient to defend the perimeter. Following an assault lasting about half an hour, the centralist garrison capitulated. Collinsworth paroled the captured centralists, most of whom retired to a point below the Rio Grande. Texian militiamen appropriated some $10,000 worth of enemy supplies, including numerous cannon. Collinsworth transferred the artillery to General Stephen F. Austin’s “Volunteer Army of the People of Texas” outside San Antonio de Béxar. -

Guadalupe, San Antonio, Mission, and Aransas Rivers and Mission, Copano, Aransas, and San Antonio Bays Basin and Bay Area Stakeholders Committee

Guadalupe, San Antonio, Mission, and Aransas Rivers and Mission, Copano, Aransas, and San Antonio Bays Basin and Bay Area Stakeholders Committee May 25, 2012 Guadalupe, San Antonio, Mission, & Aransas Rivers and Mission, Copano, Aransas, & San Antonio Bays Basin & Bay Area Stakeholders Committee (GSA BBASC) Work Plan for Adaptive Management Preliminary Scopes of Work May 25, 2012 May 10, 2012 The Honorable Troy Fraser, Co-Presiding Officer The Honorable Allan Ritter, Co-Presiding Officer Environmental Flows Advisory Group (EFAG) Mr. Zak Covar, Executive Director Texas Commission on Environmental Quality (TCEQ) Dear Chairman Fraser, Chairman Ritter and Mr. Covar: Please accept this submittal of the Work Plan for Adaptive Management (Work Plan) from the Guadalupe, San Antonio, Mission, and Aransas Rivers and Mission, Copano, Aransas and San Antonio Bays Basin and Bay Area Stakeholders Committee (BBASC). The BBASC has offered a comprehensive list of study efforts and activities that will provide additional information for future environmental flow rulemaking as well as expand knowledge on the ecosystems of the rivers and bays within our basin. The BBASC Work Plan is prioritized in three tiers, with the Tier 1 recommendations listed in specific priority order. Study efforts and activities listed in Tier 2 are presented as a higher priority than those items listed in Tier 3; however, within the two tiers the efforts are not prioritized. The BBASC preferred to present prioritization in this manner to highlight the studies and activities it identified as most important in the immediate term without discouraging potential sponsoring or funding entities interested in advancing efforts within the other tiers. -

Stormwater Management Program 2013-2018 Appendix A

Appendix A 2012 Texas Integrated Report - Texas 303(d) List (Category 5) 2012 Texas Integrated Report - Texas 303(d) List (Category 5) As required under Sections 303(d) and 304(a) of the federal Clean Water Act, this list identifies the water bodies in or bordering Texas for which effluent limitations are not stringent enough to implement water quality standards, and for which the associated pollutants are suitable for measurement by maximum daily load. In addition, the TCEQ also develops a schedule identifying Total Maximum Daily Loads (TMDLs) that will be initiated in the next two years for priority impaired waters. Issuance of permits to discharge into 303(d)-listed water bodies is described in the TCEQ regulatory guidance document Procedures to Implement the Texas Surface Water Quality Standards (January 2003, RG-194). Impairments are limited to the geographic area described by the Assessment Unit and identified with a six or seven-digit AU_ID. A TMDL for each impaired parameter will be developed to allocate pollutant loads from contributing sources that affect the parameter of concern in each Assessment Unit. The TMDL will be identified and counted using a six or seven-digit AU_ID. Water Quality permits that are issued before a TMDL is approved will not increase pollutant loading that would contribute to the impairment identified for the Assessment Unit. Explanation of Column Headings SegID and Name: The unique identifier (SegID), segment name, and location of the water body. The SegID may be one of two types of numbers. The first type is a classified segment number (4 digits, e.g., 0218), as defined in Appendix A of the Texas Surface Water Quality Standards (TSWQS). -

Application and Utility of a Low-Cost Unmanned Aerial System to Manage and Conserve Aquatic Resources in Four Texas Rivers

Application and Utility of a Low-cost Unmanned Aerial System to Manage and Conserve Aquatic Resources in Four Texas Rivers Timothy W. Birdsong, Texas Parks and Wildlife Department, 4200 Smith School Road, Austin, TX 78744 Megan Bean, Texas Parks and Wildlife Department, 5103 Junction Highway, Mountain Home, TX 78058 Timothy B. Grabowski, U.S. Geological Survey, Texas Cooperative Fish and Wildlife Research Unit, Texas Tech University, Agricultural Sciences Building Room 218, MS 2120, Lubbock, TX 79409 Thomas B. Hardy, Texas State University – San Marcos, 951 Aquarena Springs Drive, San Marcos, TX 78666 Thomas Heard, Texas State University – San Marcos, 951 Aquarena Springs Drive, San Marcos, TX 78666 Derrick Holdstock, Texas Parks and Wildlife Department, 3036 FM 3256, Paducah, TX 79248 Kristy Kollaus, Texas State University – San Marcos, 951 Aquarena Springs Drive, San Marcos, TX 78666 Stephan Magnelia, Texas Parks and Wildlife Department, P.O. Box 1685, San Marcos, TX 78745 Kristina Tolman, Texas State University – San Marcos, 951 Aquarena Springs Drive, San Marcos, TX 78666 Abstract: Low-cost unmanned aerial systems (UAS) have recently gained increasing attention in natural resources management due to their versatility and demonstrated utility in collection of high-resolution, temporally-specific geospatial data. This study applied low-cost UAS to support the geospatial data needs of aquatic resources management projects in four Texas rivers. Specifically, a UAS was used to (1) map invasive salt cedar (multiple species in the genus Tamarix) that have degraded instream habitat conditions in the Pease River, (2) map instream meso-habitats and structural habitat features (e.g., boulders, woody debris) in the South Llano River as a baseline prior to watershed-scale habitat improvements, (3) map enduring pools in the Blanco River during drought conditions to guide smallmouth bass removal efforts, and (4) quantify river use by anglers in the Guadalupe River. -

![Matching the Hatch for the TX Hill Country[2]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/3744/matching-the-hatch-for-the-tx-hill-country-2-693744.webp)

Matching the Hatch for the TX Hill Country[2]

MATCHING THE HATCH FOR THE TX HILL COUNTRY Tying and choosing proper fly patterns to increase your success on the water. Matt Bennett Fly Geek Custom Flies [email protected] Why should you listen to me? • Fishing the Austin area since 2008 • LWFF – 2012 through 2015 • Fly Geek Custom Flies – 2015 – now • Past Austin Fly Fishers President • Current TX Council Vice President Overview of the TX Hill Country Llano River near Kingsland Guadalupe River at Lazy L&L Brushy Creek near Round Rock Characteristics of Hill Country Rivers ¨ There’s a bunch! Guadalupe, Comal, San Marcos, Colorado, Llano, Blanco, Nueces, Frio, Sabinal, Concho, Lampasas and associated feeder creeks ¨ Majority are shallow and wadeable in stretches ¨ Extremely Clear Water (some clearer than others) ¨ Sandy, limestone and granite bottoms with lots of granite boulders/outcroppings ¨ Extreme flooding events YEARLY on average. Sept 11, 1952 – Lake Travis rises 57 feet in 14 hours. 23-26” of rain Guadalupe River, July 17,1987 Llano River / Lake LBJ – Nov. 4 2000 Why does flooding matter to fishing? ¨ Because of the almost-annual flooding / drought cycle of our rivers, they are constantly changing ¨ Holes get filled in and dug out, gravel gets moved around, banks get undercut ¨ We have to constantly relearn our fisheries to stay successful on the water ¨ Choosing the right flies with the proper triggers is an important part of your success on the water Overview of our forage Baitfish, crawfish, insects, and other terrestrials Why is forage important? ¨ #1 rule of all fishing – know your forage! ¨ Knowing the common forage where you fish increases your chances of success as it clues you in on what flies you should be fishing ¨ Forage base will vary between water bodies, time of year, species targeted, and more, as well as year-to-year. -

10 Most Significant Weather Events of the 1900S for Austin, Del Rio and San Antonio and Vicinity

10 MOST SIGNIFICANT WEATHER EVENTS OF THE 1900S FOR AUSTIN, DEL RIO AND SAN ANTONIO AND VICINITY PUBLIC INFORMATION STATEMENT NATIONAL WEATHER SERVICE AUSTIN/SAN ANTONIO TX 239 PM CST TUE DEC 28 1999 ...10 MOST SIGNIFICANT WEATHER EVENTS OF THE 1900S FOR AUSTIN...DEL RIO AND SAN ANTONIO AND VICINITY... SINCE ONE OF THE MAIN FOCUSES OF WEATHER IN CENTRAL AND SOUTH CENTRAL TEXAS INVOLVES PERIODS OF VERY HEAVY RAIN AND FLASH FLOODING...NOT ALL HEAVY RAIN AND FLASH FLOOD EVENTS ARE LISTED HERE. MANY OTHER WEATHER EVENTS OF SEASONAL SIGNIFICANCE ARE ALSO NOT LISTED HERE. FOR MORE DETAILS ON SIGNIFICANT WEATHER EVENTS ACROSS CENTRAL AND SOUTH CENTRAL TEXAS IN THE PAST 100 YEARS...SEE THE DOCUMENT POSTED ON THE NATIONAL WEATHER SERVICE AUSTIN/SAN ANTONIO WEBSITE AT http://www.srh.noaa.gov/images/ewx/wxevent/100.pdf EVENTS LISTED BELOW ARE SHOWN IN CHRONOLOGICAL ORDER... FIRST STARTING WITH AUSTIN AND VICINITY...FOLLOWED BY DEL RIO AND VICINITY...AND ENDING WITH SAN ANTONIO AND VICINITY. AUSTIN AND VICINITY... 1. SEPTEMBER 8 - 10... 1921 - THE REMNANTS OF A HURRICANE MOVED NORTHWARD FROM BEXAR COUNTY TO WILLIAMSON COUNTY ON THE 9TH AND 10TH. THE CENTER OF THE STORM BECAME STATIONARY OVER THRALL...TEXAS THAT NIGHT DROPPING 38.2 INCHES OF RAIN IN 24 HOURS ENDING AT 7 AM SEPTEMBER 10TH. IN 6 HOURS...23.4 INCHES OF RAIN FELL AND 31.8 INCHES OF RAIN FELL IN 12 HOURS. STORM TOTAL RAIN AT THRALL WAS 39.7 INCHES IN 36 HOURS. THIS STORM CAUSED THE MOST DEADLY FLOODS IN TEXAS WITH A TOTAL OF 215 FATALITIES. -

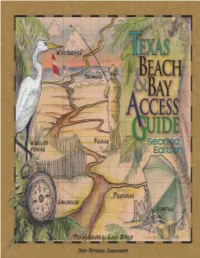

Beach and Bay Access Guide

Texas Beach & Bay Access Guide Second Edition Texas General Land Office Jerry Patterson, Commissioner The Texas Gulf Coast The Texas Gulf Coast consists of cordgrass marshes, which support a rich array of marine life and provide wintering grounds for birds, and scattered coastal tallgrass and mid-grass prairies. The annual rainfall for the Texas Coast ranges from 25 to 55 inches and supports morning glories, sea ox-eyes, and beach evening primroses. Click on a region of the Texas coast The Texas General Land Office makes no representations or warranties regarding the accuracy or completeness of the information depicted on these maps, or the data from which it was produced. These maps are NOT suitable for navigational purposes and do not purport to depict or establish boundaries between private and public land. Contents I. Introduction 1 II. How to Use This Guide 3 III. Beach and Bay Public Access Sites A. Southeast Texas 7 (Jefferson and Orange Counties) 1. Map 2. Area information 3. Activities/Facilities B. Houston-Galveston (Brazoria, Chambers, Galveston, Harris, and Matagorda Counties) 21 1. Map 2. Area Information 3. Activities/Facilities C. Golden Crescent (Calhoun, Jackson and Victoria Counties) 1. Map 79 2. Area Information 3. Activities/Facilities D. Coastal Bend (Aransas, Kenedy, Kleberg, Nueces, Refugio and San Patricio Counties) 1. Map 96 2. Area Information 3. Activities/Facilities E. Lower Rio Grande Valley (Cameron and Willacy Counties) 1. Map 2. Area Information 128 3. Activities/Facilities IV. National Wildlife Refuges V. Wildlife Management Areas VI. Chambers of Commerce and Visitor Centers 139 143 147 Introduction It’s no wonder that coastal communities are the most densely populated and fastest growing areas in the country. -

Watershed and Flow Impacts on the Mission-Aransas Estuary

Watershed and Flow Impacts on the Mission- Aransas Estuary Sarah Douglas GIS in Water Resources Fall 2016 Introduction Background Estuaries are vibrant and dynamic habitats occurring within the mixing zone of fresh and salt water. They are home to species often capable of surviving in a variety of salinities and other environmental stressors, and are often highly productive due to the high amount of nutrient input from both terrestrial and marine sources. As droughts become more common in certain areas due to climate change, understanding how species adapt, expand, or die is crucial for management strategies (Baptista et al 2010). Salinity can fluctuate wildly in back bays with limited rates of tidal exchange with the ocean and low river input, leading to changes in ecosystem structure and function (Yando et al 2016). The recent drought in Texas from 2010 to 2015 provides a chance to study the impacts of drought and river input on an estuarine system. While some studies have shown that climate changes are more impactful on Texas estuaries than changes in watershed land use (Castillo et al 2013), characterization of landcover in the watersheds leading to estuaries are important for a variety of reasons. Dissolved organic carbon and particulate organic matter influx is an important driver of microbial growth in estuaries (Miller and Shank 2012), and while DOC and POM can be generated in marine systems, terrestrial sources are also significant. Study Site The site chosen for this project is the Mission-Aransas estuary, located within the Mission-Aransas National Estuarine Research Reserve (NERR). In addition to being an ideal model of a Gulf Coast barrier island estuary, the Mission-Aransas NERR continuously monitors water parameters, weather, and nutrient data at a series of stations located within the back bays and ship channel. -

2015 Program Budget

Medina River, Catfish Farm Property PROGRAM BUDGET FISCAL YEAR 2014-2015 SAN ANTONIO RIVER AUTHORITY TEXAS PROGRAM BUDGETS July 1, 2014 - June 30, 2015 Presented to the Board of Directors Name Title County Jerry G. Gonzales Bexar County, District 1 Lourdes Galvan Bexar County, District 2 Michael W. Lackey, PE Bexar County, District 3 Thomas G. Weaver Executive Member Bexar County, District 4 Sally Buchanan Chairman Bexar County, At Large Hector R. Morales Secretary Bexar County, At Large Terry E. Baiamonte Vice-Chair Goliad County James Fuller Goliad County Gaylon J. Oehlke Treasurer Karnes County H. B. Ruckman III Karnes County Darrel T. Brownlow, Ph.D. Executive Member Wilson County John J. Flieller Wilson County Management Name Title Suzanne B. Scott General Manager Stephen T. Graham Assistant General Manager Steven J. Raabe Director of Technical Services John A. Chisholm III Director of Operations Bruce E. Knott Director of Human Resources Kristen Hansen Watershed & Park Operations Manager Claude Harding Real Estate Manager Art Herrera Information Technology Manager Steve Lusk Environmental Sciences Manager Linda Muñoz Human Resource Manager Russell Persyn Watershed Engineering Manager Steven Schauer External Communications Manager SAN ANTONIO RIVER AUTHORITY PROGRAM BUDGETS TABLE OF CONTENTS Budget Message ............................................................................................................. i Definitions .....................................................................................................................1 -

Independence Trail Region, Known As the “Cradle of Texas Liberty,” Comprises a 28-County Area Stretching More Than 200 Miles from San Antonio to Galveston

n the saga of Texas history, no era is more distinctive or accented by epic events than Texas’ struggle for independence and its years as a sovereign republic. During the early 1800s, Spain enacted policies to fend off the encroachment of European rivals into its New World territories west of Louisiana. I As a last-ditch defense of what’s now Texas, the Spanish Crown allowed immigrants from the U.S. to settle between the Trinity and Guadalupe rivers. The first settlers were the Old Three Hundred families who established Stephen F. Austin’s initial colony. Lured by land as cheap as four cents per acre, homesteaders came to Texas, first in a trickle, then a flood. In 1821, sovereignty shifted when Mexico won independence from Spain, but Anglo-American immigrants soon outnumbered Tejanos (Mexican-Texans). Gen. Antonio López de Santa Anna seized control of Mexico in 1833 and gripped the country with ironhanded rule. By 1835, the dictator tried to stop immigration to Texas, limit settlers’ weapons, impose high tariffs and abolish slavery — changes resisted by most Texans. Texas The Independence ★ ★ ★ ★ ★ ★ ★ Trail ★ ★ ★ ★ ★ ★ ★ On March 2, 1836, after more than a year of conclaves, failed negotiations and a few armed conflicts, citizen delegates met at what’s now Washington-on-the-Brazos and declared Texas independent. They adopted a constitution and voted to raise an army under Gen. Sam Houston. TEXAS STATE LIBRARY AND ARCHIVES Gen. Sam Houston THC The San Jacinto Monument towers over the battlefield where Texas forces defeated the Mexican Army. TEXAS HISTORICAL COMMISSION Four days later, the Alamo fell to Santa Anna. -

Commercial Fishing Full Final Report Document Printed: 11/1/2018 Document Date: January 21, 2005 2

1 ECONOMIC ACTIVITY ASSOCIATED WITH COMMERCIAL FISHING ALONG THE TEXAS GULF COAST Joni S. Charles, PhD Contracted through the River Systems Institute Texas State University – San Marcos For the National Wildlife Federation February 2005 Commercial Fishing Full Final Report Document Printed: 11/1/2018 Document Date: January 21, 2005 2 Introduction This report focuses on estimating the economic activity specifically associated with commercial fishing in Sabine Lake/Sabine-Neches Estuary, Galveston Bay/Trinity-San Jacinto Estuary, Matagorda Bay/Lavaca-Colorado Estuary, San Antonio Bay/Guadalupe Estuary, Aransas Bay/Mission-Aransas Estuary, Corpus Christi Bay/Nueces Estuary, Baffin Bay/Upper Laguna Madre Estuary, and South Bay/Lower Laguna Madre Estuary. Each bay/estuary area will define a separate geographic region of study comprised of one or more counties. Commercial fishing, therefore, refers to bay (inshore) fishing only. The results show the ex-vessel value of finfish, shellfish and shrimp landings in each of these regions, and the impact this spending had on the economy in terms of earnings, employment and sales output. Estimates of the direct impacts associated with ex-vessel values were produced using IMPLAN, an input-output of the Texas economy developed by the Minnesota IMPLAN Group. The input data was obtained from the Texas Parks and Wildlife Department (TPWD) (Culbertson 2004). Commercial fishing impacts are provided in terms of direct expenditure, sales output, income, and employment. These estimates are reported by category of expenditure. A description of IMPLAN is included in Appendix C. Indirect and Induced (Secondary) impacts are generated from the direct impacts calculated by IMPLAN. Indirect impacts represent purchases made by industries from their suppliers. -

Jeanne Albrecht, PR Coordinator Sellmark 210-392-9047 [email protected] (Please Email Or Call for Photos, Videos, Advance Interviews, Etc.) October 2015

Media Contact: Jeanne Albrecht, PR Coordinator Sellmark 210-392-9047 [email protected] (Please email or call for photos, videos, advance interviews, etc.) October 2015 For Immediate Release: Washington on the Brazos to mark 180th Anniversary of Texas Independence and 100th Birthday of this State Park 2016 will be an especially important year for Washington on the Brazos State Historic Site: not only is it the 180th anniversary of the signing of the Texas Declaration of Independence from Mexico in 1836 at Washington on the Brazos, but it will also be the state park's 100th birthday. It was March 2, 1836 when 59 delegates bravely met in Washington, Texas to make a formal declaration of independence from Mexico. From 1836 until 1846, the Republic of Texas proudly existed as a separate nation. To commemorate the 180th anniversary of Texas Independence, the three entities that administer and support this site—Texas Parks & Wildlife Dept (TPWD), Blinn College and Washington on the Brazos State Park Association—are planning some Texas-sized celebrations. “Texas Independence Day Celebration” (TIDC) is an annual two-day celebration from 10 a.m. to 5 p.m. on Saturday, March 5 and Sunday, March 6, 2016 on the expansive 293-acre park grounds and its three incredible attractions: Star of the Republic Museum (collections and programs honoring history of early Texans, administered by Blinn College); Independence Hall (replica of the site where representatives wrote the Texas Declaration of Independence); and Barrington Living History Farm (where interpreters dress, work and farm as did the original residents of this homestead).