Some Conclusions I. Early Qur'an Manuscripts

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Qur'anic Manuscripts

The Qur'anic Manuscripts Introduction 1. The Qur'anic Script & Palaeography On The Origins Of The Kufic Script 1. Introduction 2. The Origins Of The Kufic Script 3. Martin Lings & Yasin Safadi On The Kufic Script 4. Kufic Qur'anic Manuscripts From First & Second Centuries Of Hijra 5. Kufic Inscriptions From 1st Century Of Hijra 6. Dated Manuscripts & Dating Of The Manuscripts: The Difference 7. Conclusions 8. References & Notes The Dotting Of A Script And The Dating Of An Era: The Strange Neglect Of PERF 558 Radiocarbon (Carbon-14) Dating And The Qur'anic Manuscripts 1. Introduction 2. Principles And Practice 3. Carbon-14 Dating Of Qur'anic Manuscripts 4. Conclusions 5. References & Notes From Alphonse Mingana To Christoph Luxenberg: Arabic Script & The Alleged Syriac Origins Of The Qur'an 1. Introduction 2. Origins Of The Arabic Script 3. Diacritical & Vowel Marks In Arabic From Syriac? 4. The Cover Story 5. Now The Evidence! 6. Syriac In The Early Islamic Centuries 7. Conclusions 8. Acknowledgements 9. References & Notes Dated Texts Containing The Qur’an From 1-100 AH / 622-719 CE 1. Introduction 2. List Of Dated Qur’anic Texts From 1-100 AH / 622-719 CE 3. Codification Of The Qur’an - Early Or Late? 4. Conclusions 5. References 2. Examples Of The Qur'anic Manuscripts THE ‘UTHMANIC MANUSCRIPTS 1. The Tashkent Manuscript 2. The Al-Hussein Mosque Manuscript FIRST CENTURY HIJRA 1. Surah al-‘Imran. Verses number : End Of Verse 45 To 54 And Part Of 55. 2. A Qur'anic Manuscript From 1st Century Hijra: Part Of Surah al-Sajda And Surah al-Ahzab 3. -

Bulletin of the School of Oriental and African Studies When Did The

Bulletin of the School of Oriental and African Studies http://journals.cambridge.org/BSO Additional services for Bulletin of the School of Oriental and African Studies: Email alerts: Click here Subscriptions: Click here Commercial reprints: Click here Terms of use : Click here When did the consonantal skeleton of the Quran reach closure? Part II Nicolai Sinai Bulletin of the School of Oriental and African Studies / FirstView Article / May 2014, pp 1 - 13 DOI: 10.1017/S0041977X14000111, Published online: 22 May 2014 Link to this article: http://journals.cambridge.org/abstract_S0041977X14000111 How to cite this article: Nicolai Sinai When did the consonantal skeleton of the Quran reach closure? Part II . Bulletin of the School of Oriental and African Studies, Available on CJO 2014 doi:10.1017/S0041977X14000111 Request Permissions : Click here Downloaded from http://journals.cambridge.org/BSO, IP address: 128.250.144.144 on 27 May 2014 Bulletin of SOAS, Page 1 of 13. © SOAS, University of London, 2014. doi:10.1017/S0041977X14000111 When did the consonantal skeleton of the Quran reach closure? Part II1 Nicolai Sinai Oriental Institute, University of Oxford [email protected] Abstract The Islamic tradition credits the promulgation of a uniform consonantal skeleton (rasm) of the Quran to the third caliph ʿUthmān (r. 644–656). However, in recent years various scholars have espoused a conjectural dat- ing of the Quran’s codification to the time of ʿAbd al-Malik, or have at least taken the view that the Islamic scripture was open to significant revi- sion up until c. 700 CE. The second instalment of this two-part article sur- veys arguments against this hypothesis. -

Towards a Reconstruction of the Muʿtazili Tradition of Qurʾanic

________4 ________ Aims, Methods and Towards a Reconstruction of the Muctazi II Tradition of Contexts of Qur'anic Exegesis: Reading the Qur'anic Exegesis Introduction to the TahdhTb of al-tJakim ai-JishumT (d. 494/1101) (2nd/8th-9th/15th c.) and Its Application· EDITED BY SULEIMAN A. MOURAD Karen Bauer HE Tahdhib fi taftirai-Qur'an (The Refinement in the Interpretation Tof the Qur'an), by the Mu'tazili scholar and theologian al-l:lakim al-Jishumi (d. 494/1101), represents, to date, our best source for under standing the Mu'tazili tradition ofQur'anic exegesis.' Yet, this massive work that comprises nine volumes2 is only available in manuscript form, and is therefore inaccessible to most scholars ofQur'anic Studies. The only published Mu'tazili tafsir is Tafsir al-kashshiif by Jar Allah MaQ.mud b. •u mar al·Zamakhshari (d 538/1144), who does not furnish in his introduction the hermeneutical approach and methodology he adopts for interpreting the Qur'an, although in the main body of the Kashshiif the reader can identify some elements that belong to a hermeneutical approach and methodology.3 In contrast, Jishumi lays • This essay is based on a monograph in preparation on Jishumi and his exegesis of the Qur'an entitled The Mu'tazila at1d Qur'anic Henuctleutics: A Study ofal-J:(iikirn al-Jisi1Uml's Exegesis: al-Tahdhib fltafsir al-Qur'nn, facilitated by a fellowship from OXFORD the National Endowment for the Humanities and a Franklin Research Grant from the UNrvJIUITY l'IJIII American Philosophical Society. An earlier version of this paper, entitled 'The in association with Revealed Text and the Intended Subtext: Notes on the Hermeneutics ofthe Qur'an in Mu'tazila Discourse as Reflected in the Tahdhibof al-l:faldm ai-Jishumi (d.494/1101)', THE INSTITUTE OF ISMAfLI STUDIES appeared in Felicitas Opwis and David Reisman, eds., Islamic Philosophy, Scic11cc, LONDON Culture, arrd Religiorr: Studies in Horror ofDimitri Gulas (Leiden, 2011), pp. -

An Analytical Study of Women-Related Verses of S¯Ura An-Nisa

Gunawan Adnan Women and The Glorious QurÞÁn: An Analytical Study of Women-RelatedVerses of SÙra An-NisaÞ erschienen in der Reihe der Universitätsdrucke des Universitätsverlages Göttingen 2004 Gunawan Adnan Women and The Glorious QurÞÁn: An Analytical Study of Women- RelatedVerses of SÙra An-NisaÞ Universitätsdrucke Göttingen 2004 Die Deutsche Bibliothek – CIP-Einheitsaufnahme Ein Titelsatz für diese Publikation ist bei der Deutschen Bibliothek erhältlich. © Alle Rechte vorbehalten, Universitätsverlag Göttingen 2004 ISBN 3-930457-50-4 Respectfully dedicated to My honorable parents ...who gave me a wonderful world. To my beloved wife, son and daughter ...who make my world beautiful and meaningful as well. i Acknowledgements All praises be to AllÁh for His blessing and granting me the health, strength, ability and time to finish the Doctoral Program leading to this book on the right time. I am indebted to several persons and institutions that made it possible for this study to be undertaken. My greatest intellectual debt goes to my academic supervisor, Doktorvater, Prof. Tilman Nagel for his invaluable advice, guidance, patience and constructive criticism throughout the various stages in the preparation of this dissertation. My special thanks go to Prof. Brigitta Benzing and Prof. Heide Inhetveen whose interests, comments and guidance were of invaluable assistance. The Seminar for Arabic of Georg-August University of Göttingen with its international reputation has enabled me to enjoy a very favorable environment to expand my insights and experiences especially in the themes of Islamic studies, literature, phylosophy, philology and other oriental studies. My thanks are due to Dr. Abdul RazzÁq Weiss who provided substantial advice and constructive criticism for the perfection of this dissertation. -

Nota Ringkasan Asas Tajwid Al-Qur'an

FATEHAH LEARNING CENTRE ILMU . AMAL . AMAN . NOTA RINGKASAN ASAS TAJWID AL-QUR’AN RASM ‘UTHMANI RIWAYAT HAFS IMAM ‘ASIM ‘ Kuasai Ilmu Tajwid Dengan Mudah ’ ‘ Seronoknya Cinta Al-Qur’an ’ Disusun oleh: Ahmad Fitri Bin Mat Rusop Disemak oleh: Mohd Izwan Bin Ahmad FATEHAH LEARNING CENTRE 27-2, Jalan Wangsa Delima 2A, Syeksen 5 Wangsa Maju, 53300 Kuala Lumpur WhatsApp: 011 - 1621 7797 Tel: 03 - 4131 9057 FATEHAH LEARNING CENTRE Seronoknya Cinta Al-Quran KANDUNGAN BIL PERKARA MUKA SURAT 1 Pengenalan 3 2 Makhraj Huruf 5 3 Alif Lam Ma’rifah 10 4 Hukum Bacaan Nun Mati Dan Tanwin 11 5 Hukum Bacaan Mim Mati 14 6 Bacaan Mim Dan Nun Syaddah 15 7 Jenis-jenis Idgham 16 8 Jenis-jenis Mad 17 9 Hukum Bacaan Ra 24 10 Hukum Bacaan Lam Pada Lafaz Al-Jalalah 25 11 Qalqalah 25 12 Tanda-tanda Waqaf 26 13 Cara Bacaan Hamzah Wasal 27 14 Iltiqa’ Sakinain / Nun Al-Wiqayah 28 15 Bacaan-bacaan Gharib dalam Al-Qur’an 29 2 FATEHAH LEARNING CENTRE Seronoknya Cinta Al-Quran PENGENALAN PENGERTIAN TAJWID Tajwid dari sudut bahasa bermaksud memperelokkan atau memperindahkan. Dari sudut istilah pula, Tajwid bererti megeluarkan huruf dari tempatnya dengan memberikan hak sifat-sifat yang dimilikinya. Ringkasnya, ilmu tajwid adalah ilmu tentang cara membaca Al-Quran dengan baik dan betul. TUJUAN MEMPELAJARI ILMU TAJWID Supaya dapat membaca ayat suci Al-Qur’an secara fasih (betul/benar), lancar, serta dapat memelihara lidah dari kesalahan-kesalahan ketika membaca al-Qur'an. HUKUM MEMPELAJARI ILMU TAJWID Hukum mempelajari Ilmu Tajwid adalah Fardhu Kifayah. Akan tetapi, hukum mengamalkan tajwid di ketika membaca Al-Qu’an adalah Fardhu ‘Ain, atau wajib ke atas setiap lelaki dan perempuan yang mukallaf. -

Rasm Mushaf Usmany Dan Rahasianya 43

Rasm Mushaf Usmany Dan Rahasianya 43 Rasm Mushaf Usmany Dan Rahasianya (Sebuah kajian tentang bukti. baru kemu'jizatan. AI-Qur'an) Abdul Aziz Penulis adalah DosenUIN Ma/ang ABSTRACT Syalabi wrote, in his book that Abu Bakar has collected Al-Qur'an comprising seven readings which are allowed to be read He did not specifyon one certain reading. ' A lot ofhisfriends.also had their own mushaf The differences, then, caused the different reading among Iraq and Syamsociety. This dispute made Khudzaifahbin al-Yaman was angry. He informed it to Usman bin A/Janr. a. and finallyUsman united the people in one letter or one reading and rasm. Pendahulan AI-Qur'an turun kepada Nabi Muhammad SAW pada saat kondisi baca tulis di dunia arab sedang langka. Bahkan sampai pada saat al-Qur'an ditulis, tulisan itu belum sempurna sebagaimana yang ada pada tulisan bahasa Arab sekarang. Al-Qur'an saat itu ditulis dengan tanpa titik dan tanpa harakat. Sehingga keterbatasan model tulfsan Arab tersebut seringkali menjadi senjata _para orientalis untuk UlulAlbab, Vol. 4 No. 1, 2003 44 Abdul Aziz melemahkan al-Qur'an dan Islam. Dalam makalah berikut insya Allah akan kita bahas secara singkat. Al-Qur'an baru dibukukan beberapa tahun kemudian setelah pada perang Yamamah banyak panghafalal-Qur'an yang meninggal dalam peperangan tersebut. Kondisi ini banyak meresahkan para sahabat, karena umat Islam sering terlibat peperangan. Dan setiap peperangan selalu banyak menggugurkan para sahabat. Kegelisahan itu sangat dirasakan terutama oleh Umar bin Khaththab. Dan atas usulan beliau akhirnya al-Qur'an ditulis pada masa khalifahAbu Bakar r.a. -

Investigation on the Ancient Quran Folios of Birmingham H

Investigation on the Ancient Quran Folios of Birmingham H. Sayoud Investigation on the Ancient Quran Folios of Birmingham Halim Sayoud http://sayoud.net SUMMARY In 2015, some scientists of the University of Birmingham discovered that four folios containing some ancient Quran manuscripts dated from the period of the Prophet’s companions ( i.e. few years after the death of the Prophet ). In fact a radiocarbon analysis showed that there is a 95.4% chance that the parchment on which the Qur'an fragments were written can be dated sometime between the years 568 and 645CE. This means that the animal from which the skin was taken was living sometime between these dates. Furthermore, we know that the Prophet lived between 570 and 632CE, which makes this discovery quite interesting by showing that this manuscript could be one of the oldest manuscripts in the world, or at least dating from the first centuries after the Prophet death. In this investigation, we are not going to confirm that discovery, but only checking whether the ancient text is similar to the present Quran or not. The first results based on character analysis, word analysis, phonetic analysis and semantic analysis have shown that the Birmingham Quran manuscript is similar to its corresponding part contained in the present Quran (Hafs recitation ). According to this investigation, it appears that the Quran has been safely preserved during the last 14 centuries without alteration. 1. Introduction on the Birmingham Quran manuscript The Birmingham Quran manuscript consists in four pages made of parchment, written in ink, and containing parts of chapters 18, 19 and 20 of the holy Quran. -

Radiocarbon (14C) Dating of Qurʾān Manuscripts

chapter 6 Radiocarbon (14C) Dating of Qurʾān Manuscripts Michael Josef Marx and Tobias J. Jocham According to 14C measurements, the four Qurʾān fragments University Library Tübingen Ma VI 165, Berlin State Library We. II 1913 and ms. or. fol. 4313, and University Library Leiden Cod. or. 14.545b/c are older than had been pre- sumed due to their paleographical characteristics. Within the framework of the joint German-French project Coranica, Qurʾān manuscripts and other texts of Late Antiquity (Syriac Bible manuscripts, Georgian manuscripts, dated Ara- bic papyri, etc.) have been dated for comparison and turn out to be reliable according to dating by 14C measurement. This article emphasizes the impor- tance of combining 14C measurements with paleographical characteristics and orthography when dating Qurʾān fragments. The archaic spelling that appears within the four fragments (e.g., of the words Dāwūd, ḏū, or šayʾ) demonstrates that Arabic orthography in the text of the Qurʾān was still developing during the 7th and 8th centuries. The fact that the long vowel /ā/ was—in the early manuscripts—spelled using wāw or yāʾ in the middle of a word, rarely using alif whose original phonetic value is the glottal stop (hamza), led to spellings that are now obsolete. Alongside orthographic and paleographical questions, the large number of fragments in Ḥiǧāzī spelling urges us to reconsider the role that written transmission plays within the textual history of the Qurʾān. 1 Introduction In the last years, several manuscripts of the Qurʾān and other -

Effective Techniques of Memorizing the Quran: a Study at Madrasah Tahfiz Al-Quran, Terengganu, Malaysia

Middle-East Journal of Scientific Research 13 (1): 45-48, 2013 ISSN 1990-9233 © IDOSI Publications, 2013 DOI: 10.5829/idosi.mejsr.2013.13.1.1762 Effective Techniques of Memorizing the Quran: A Study at Madrasah tahfiz Al-quran, Terengganu, Malaysia 1Sedek Ariffin,1Mustaffa Abdullah, 1Ishak Suliaman, 1Khadher Ahmad, 1Fauzi Deraman, 1Faisal Ahmad Shah, 1Mohd Yakub Zulkifli Mohd Yusoff, 1Monika Munirah Abd Razzak, 1Mohd Murshidi Mohd Noor, 1Jilani Touhami Meftah, 1Ahmad K Kasar, 1Selamat Amir and 2Mohd Roslan Mohd Nor 1Department of al-Quran and al-Hadith, Academy of Islamic Studies, University of Malaya, 50603 Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia 2Department of Islamic History and Civilization, Academy of Islamic Studies, University of Malaya, 50603 Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia Abstract: Until today, memorization is still one of the methods used in the process of preservation of al-Qur’an. This article aims to review and analyze the methods and approaches used by a Centre of Tahfiz al-Qur’an, namely Madrasah Quran, Terengganu, Malaysia in the process to produce the students that can memorize the whole al-Qur’an. This study used the methods of documentation, observation and interviews in order to obtain the data. Through the analysis, this study found that there are four basic methods of memorizing al-Qur’an. The methods are Sabak method, Para Sabak, Ammokhtar and Halaqah Dauri. By using these four methods, the students could recite the whole Qur’an by memorization, within 15 hours without seeing the mushaf. These methods of memorization could be applied in all Quranic memorization centers in order to produce the huffaz who can fully remember the whole Qur’an. -

Learning Concepts and Educational Development of Hafazan Al-Quran in the Early Islamic Century

International Journal of Academic Research in Business and Social Sciences 2017, Vol. 7, No. 10 ISSN: 2222-6990 Learning Concepts and Educational Development of Hafazan Al-Quran in the Early Islamic Century Ahmad Rozaini Ali Hasan1*, Abd Rahman Abd Ghani2, Misnan Jemali3, Nur Fatima Wahida Mohd Nasir4, Muhammad Yusri Muhammad Yusuf5 and Mohd Farhan Md Ariffin6 1*, 5, 6 Academy of Contemporary Islamic Studies, Universiti Teknologi MARA (UiTM) Perak Branch, Seri Iskandar Campus, Perak, Malaysia 4 Academy of Language Studies, Universiti Teknologi MARA (UiTM) Perak Branch, Seri Iskandar Campus, Seri Iskandar, Perak, Malaysia 2, 3 Department of Islamic Studies, Faculty of Human Science, University Pendidikan Sultan Idris Tanjong Malim, Malaysia 3 Faculty of Education, Kolej Universiti Perguran Ugama, Seri Begawan, Brunei Darussalam 6Academy of Islamic Studies, Universiti Malaya, Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia DOI: 10.6007/IJARBSS/v7-i10/3417 URL: http://dx.doi.org/10.6007/IJARBSS/v7-i10/3417 Abstract The process of learning hafazan al-Quran is quite different and unique compared to other learning approaches in the Islamic field. This is because teaching and learning hafazan focuses more on the aspect of character development among students. It is imperative that teachers must understand the learning factors of hafazan al-Quran to ensure quality knowledge of the hafazan among students. Therefore, this paper discusses on the history and development of hafazan al-Quran starting from the early teachings of the Prophet Muhammad SAW and his friends. The impressive hafazan skills showed by the people of the early Islamic era reflected their commitment and high interest in understanding and memorizing the al-Quran. -

Three Qurʾānic Folios from a Collection in Finland

THREE QURʾĀNIC FOLIOS FROM A COLLECTION IN FINLAND Ilkka Lindstedt University of Helsinki This is a contribution to the study of the Qurʾānic text through an edition and study of three folios, called K176, K182, and K185, that are paleographically relatively early. The folios do not belong to the same codex but are separate leaves; they are kept at a private collection in Finland called the Ilves Collection. We can place them, tentatively, to the third/ninth century. The Qurʾānic folios presented here attest some variant spellings to the text of the Cairo Royal edition. The parchments have, in many cases, the scriptio plena where Cairo has a more defective writing (the medial ā). They give us more evidence that the rasm of Qurʾānic manuscripts was not completely stable. INTRODUCTION Research into the textual history of the Qurʾān has progressed immensely in recent decades with the study of early Qurʾānic codices and fragments.1 Of these studies, one can mention especially Jeffery & Mendelsohn (1942) and Ibn Warraq (2011) on the Samarqand codex; Déroche (2009) on the Codex Parisino-Petropolitanus and (2014) on the Umayyad-era Qurʾāns in general; G. Puin (2011) on the Ṣanʿāʾ manuscripts; as well as Small (2011) for a comparison of the early Qurʾānic manuscripts. For other recent significant studies on the Qurʾān, see McAuliffe (2006), Reynolds (2008), and Neuwirth et al. (2011). Scholars should also note the translation of Theodor Nöldeke’s work into English (2013). The recent studies seem to indicate that the Qurʾānic rasm, consonantal skeleton, became more or less stable very on and the variants in the early Qurʾānic manuscripts concern mostly orthography: whether and how to write the hamza, how to write the long vowel ā, especially the medial one, and so on. -

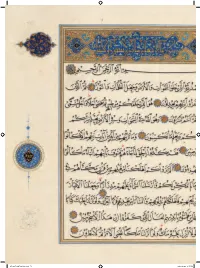

Visual Codifications of the Qur'an Between 1000 and 1700

076-097 224720 CS6.indd 76 2016-09-02 1:55 PM Shaping the Word of God: Visual Codifications of the Qur’an between 1000 and 1700 ¡¢£¤ ¥¦§§¡¨ Today, a printed copy of the Qur’an looks disnctly unlike any other pe of book wrien in Arabic script.1 e Holy Book of Islam, the Word of God for Muslims, oen is published in a single volume, with a dense display of text on the page and a limited selecon of standardized fonts: naskh for the text, thuluth for the chapter (sura) tles. e modern, mass-produced mushaf (plural: masahif), the Arabic word for a wrien copy of the Qur’an, is a singular book object, unique in sle and format. When Muslims and non-Muslims alike are asked to picre the Qur’an, oen what comes to mind is an austere book, with both text and decorave elements rendered in black and white. Such elements include the opening double-page spread with the first sura on the right and the beginning of the second chapter on the le page. All the subsequent chapter tles are presented in framed and decorated headings (unwan). e text on every page is also enclosed in a simple framing border. roughout the book, inscribed medallions in the margins indicate divisions of the text. Appearing oen, though not always, are numerical markers of the thir-secon divisions (juz; plural: ajza’), and more occasionally their subdivisions: rub‘ (quarter), nisf (half), thalatha arba‘ (three- fourths) as well as the fourteen indicaons of prosaon (sajda). Finally, small, idencal devices inserted in the text separate verses (aya) and present the posion number of the preceding aya.