Cover Page the Handle

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ukiyoe : L’Arte Che Danza La Danza Giapponese Nelle Immagini Del Mondo Fluttuante

Corso di Laurea magistrale in Lingue e Civiltà dell’Asia e dell’Africa mediterranea Tesi di Laurea Ukiyoe : l’arte che danza La danza giapponese nelle immagini del mondo fluttuante. Relatore Ch. Prof. Silvia Vesco Correlatore Ch. Prof. Bonaventura Ruperti Laureando Claudia Mancini Matricola 820625 Anno Accademico 2013 / 2014 Ai miei genitori e ai miei amici in giro per mondo, mio cuore e forza. UKIYOE: L’ARTE CHE DANZA. La danza giapponese nelle immagini del mondo fluttuante. 序文 ............................................................................................ 1 PARTE I – Sulle immagini dell’ ukiyoe ......................................... 6 1. Il termine ukiyo e il contesto storico-sociale .......................... 7 2. Lo sviluppo, la tecnica e i formati ....................................... 14 3. I grandi maestri e i soggetti ................................................. 18 PARTE II – Sulla danza giapponese .......................................... 31 4. Introduzione: la danza e il suo linguaggio ........................... 32 5. La danza nel Giappone antico ............................................. 35 5.1. All’origine la danza ........................................................ 35 5.2. La danza come rituale: dal mito il kagura ...................... 41 5.3. La danza arriva a corte: gigaku e bugaku ........................ 49 6. La danza tra il IX e il XIII secolo ......................................... 64 6.1. Dalla corte al popolo: sangaku, sarugaku e dengaku ....... 64 6.2. La danza come cambiamento: -

El Ciclo De Las Horas En Grabado Japonés Ukiyo-E Del Periodo Edo (1615-1868) V

EL RELOJ DE LA GEISHA: EL CICLO DE LAS HORAS EN GRABADO JAPONÉS UKIYO-E DEL PERIODO EDO (1615-1868) V. David Almazán Tomás* 1. La medición tradicional de las horas en Japón Las costumbres europeas para computar el tiempo difieren de las desarro- lladas por los japoneses a lo largo de su historia.1 En 1872, el gobierno refor- mista de la era Meiji (1868-1912) adoptó el calendario gregoriano y se cambió también la forma de medir la duración de las horas, que hasta entonces eran doce para todo el día. Aproximadamente sus horas eran como dos de las nues- tras, si bien esas doce horas tenían duración diferente por el día y por la noche. En el invierno, las horas de la noche son más largas que en el verano. La salida y la puesta de sol son los límites de las seis horas del día y las seis horas de la noche. Esas seis horas, en lugar de contarlas progresivamente, se computaban como en una cuenta atrás, comenzando por el número superior, del nueve al cuatro.2 Además de esta numeración, tan ajena a la que estamos acostumbra- dos, otra peculiaridad era que, además de los números, los japoneses también * Departamento de Historia del Arte de la Universidad de Zaragoza. HAR2014-55851-P y HAR2013-45058-P, Grupo «Japón» del Gobierno de Aragón y de la Universidad de Zaragoza. E-mail: [email protected] 1 Los japoneses por influencia china emplean con regularidad desde el siglo vii un sis- tema de eras denominado nengo que se determinaba por el reinado del emperador y tam- bién el Ciclo Sexagenario, un complejo sistema astrológico de vástagos celestiales y animales del zodiaco. -

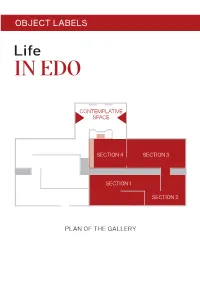

Object Labels

OBJECT LABELS CONTEMPLATIVE SPACE SECTION 4 SECTION 3 SECTION 1 SECTION 2 PLAN OF THE GALLERY SECTION 1 Travel Utagawa Hiroshige Procession of children passing Mount Fuji 1830s Hiroshige playfully imitates with children a procession of a daimyo passing Mt Fuji. A popular subject for artists, a daimyo and his entourage could make for a lively scene. During Edo, daimyo were required to travel to Edo City every other year and live there under the alternate attendance (sankin- kōtai) system. Hundreds of retainers would transport weapons, ceremonial items, and personal effects that signal the daimyo’s military and financial might. Some would be mounted on horses; the daimyo and members of his family carried in palanquins. Cat. 5 Tōshūsai Sharaku Actor Arashi Ryūzō II as the Moneylender Ishibe Kinkichi 1794 Kabuki actor portraits were one of the most popular types of ukiyo-e prints. Audiences flocked to see their favourite kabuki performers, and avidly collected images of them. Actors were stars, celebrities much like the idols of today. Sharaku was able to brilliantly capture an actor’s performance in his expressive portrayals. This image illustrates a scene from a kabuki play about a moneylender enforcing payment of a debt owed by a sick and impoverished ronin and his wife. The couple give their daughter over to him, into a life of prostitution. Playing a repulsive figure, the actor Ryūzō II made the moneylender more complex: hard-hearted, gesturing like a bully – but his eyes reveal his lack of confidence. The character is meant to be disliked by the audience, but also somewhat comical. -

Japanese Art Contents

2 0 0 9 / 2 0 1 0 Japanese Art Japanese Contents Japanese Art at Brill Hotei Publishing, established in Leiden in 1998, became an imprint of Brill in 2006. As part of Brill’s Asian Studies program, Hotei specializes in books related to Japanese art, and publishes exhibition catalogues and lavishly-illustrated books on established and lesser-known Japanese print artists and painters, as well as a variety of other facets of Japanese art and culture. Hotei Publishing works with an international team of museum curators, art historians and specialist authors. Recent projects that illustrate Hotei’s close cooperation with museums are Reading Surimono, The Interplay of Text and Image in Japanese Prints, published in association with the Museum Rietberg in Zurich, and the catalog of the magnificent surimono holdings in the See page 9 See page 5 See page 8 Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam, which will appear shortly. Japanese art will also have a prominent place in Brill’s new academic book series Japanese Visual Culture. The inaugural volume of the series will be Chōgen, The Holy One, And The Restoration Of Japanese Buddhist art by the eminent scholar John Rosenfield. With a strong editorial board, led by John T. Carpenter (SOAS, University of London/Sainsbury Institute for the Study of Japanese Arts and Cultures) we aim to publish groundbreaking research on Japanese art and visual culture in an attractive format. We hope you will enjoy browsing our catalog and will visit brill.nl for more detailed and updated information on Hotei Publishing’s titles. Our own webpage at brill.nl/hotei features background information and news. -

Ukiyo-E: Pictures of the Floating World

Ukiyo-e: pictures of the Floating World The V&A's collection of ukiyo- e is one of the largest and finest in the world, with over 25,000 prints, paintings, drawings and books. Ukiyo-e means 'Pictures of the Floating World'. Images of everyday Japan, mass- produced for popular consumption in the Edo period (1615-1868), they represent one of the highpoints of Japanese cultural achievement. Popular themes include famous beauties and well-known actors, renowned landscapes, heroic tales and folk stories. Oniwakamaru subduing the Giant Carp (detail), Totoya Hokkei, In the Edo period (1615- about 1830-1832. Museum no. E.3826:1&2-1916 1868), fans provided a popular format for print designers' ingenuity and imagination. The designs produced for fans are usually themed around summer, festivals, and the lighter side of life. Ukiyo-e prints from the collection are available for study in the V&A Prints and Drawings study room. What are ukiyo-e? The art of ukiyo-e is most frequently associated with colour woodblock prints, popular in Japan from their development in 1765 until the closing decades of the Meiji period Source URL: http://www.vam.ac.uk/content/articles/u/ukiyo-e-pictures-of-the-floating-world/ Saylor URL: http://www.saylor.org/courses/arth305/#3.4.2 © Victoria and Albert Museum Saylor.org Used by permission. Page 1 of 8 (1868-1912). The earliest prints were simple black and white prints taken from a single block. Sometimes these prints were coloured by hand, but this process was expensive. In the 1740s, additional woodblocks were used to print the colours pink and green, but it wasn't until 1765 that the technique of using multiple colour woodblocks was perfected. -

Fine Japanese and Korean Art New York I September 12, 2018 Fine Japanese and Korean Art Wednesday 12 September 2018, at 1Pm New York

Fine Japanese and Korean Art New York I September 12, 2018 Fine Japanese and Korean Art Wednesday 12 September 2018, at 1pm New York BONHAMS BIDS INQUIRIES CLIENT SERVICES 580 Madison Avenue +1 (212) 644 9001 Japanese Art Department Monday – Friday 9am-5pm New York, New York 10022 +1 (212) 644 9009 fax Jeffrey Olson, Director +1 (212) 644 9001 www.bonhams.com [email protected] +1 (212) 461 6516 +1 (212) 644 9009 fax [email protected] PREVIEW To bid via the internet please visit ILLUSTRATIONS Thursday September 6 www.bonhams.com/24862 Takako O’Grady, Front cover: Lot 1082 10am to 5pm Administrator Back cover: Lot 1005 Friday September 7 Please note that bids should be +1 (212) 461 6523 summited no later than 24hrs [email protected] 10am to 5pm REGISTRATION prior to the sale. New bidders Saturday September 8 IMPORTANT NOTICE 10am to 5pm must also provide proof of identity when submitting bids. Please note that all customers, Sunday September 9 irrespective of any previous activity 10am to 5pm Failure to do this may result in your bid not being processed. with Bonhams, are required to Monday September 10 complete the Bidder Registration 10am to 5pm Form in advance of the sale. The form LIVE ONLINE BIDDING IS Tuesday September 11 can be found at the back of every AVAILABLE FOR THIS SALE 10am to 3pm catalogue and on our website at Please email bids.us@bonhams. www.bonhams.com and should SALE NUMBER: 24862 com with “Live bidding” in the be returned by email or post to the subject line 48hrs before the specialist department or to the bids auction to register for this service. -

Marr, Kathryn Masters Thesis.Pdf (4.212Mb)

MIRRORS OF MODERNITY, REPOSITORIES OF TRADITION: CONCEPTIONS OF JAPANESE FEMININE BEAUTY FROM THE SEVENTEENTH TO THE EARLY TWENTIETH CENTURY A thesis submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts in Japanese at the University of Canterbury by Kathryn Rebecca Marr University of Canterbury 2015 Table of Contents Acknowledgements ·········································································· 1 Abstract ························································································· 2 Notes to the Text ·············································································· 3 List of Images·················································································· 4 Introduction ···················································································· 10 Literature Review ······································································ 13 Chapter One Tokugawa Period Conceptions of Japanese Feminine Beauty ························· 18 Eyes ······················································································ 20 Eyebrows ················································································ 23 Nose ······················································································ 26 Mouth ···················································································· 28 Skin ······················································································· 34 Physique ················································································· -

Japanese Prints of the Floating World

James Madison University JMU Scholarly Commons Senior Honors Projects, 2020-current Honors College 5-8-2020 Savoring the moon: Japanese prints of the floating world Madison Dalton James Madison University Follow this and additional works at: https://commons.lib.jmu.edu/honors202029 Part of the Acting Commons, Art Education Commons, Asian Art and Architecture Commons, Buddhist Studies Commons, Fine Arts Commons, History of Religions of Eastern Origins Commons, Japanese Studies Commons, Modern Art and Architecture Commons, and the Other History of Art, Architecture, and Archaeology Commons Recommended Citation Dalton, Madison, "Savoring the moon: Japanese prints of the floating world" (2020). Senior Honors Projects, 2020-current. 10. https://commons.lib.jmu.edu/honors202029/10 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Honors College at JMU Scholarly Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Senior Honors Projects, 2020-current by an authorized administrator of JMU Scholarly Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Savoring the Moon: Japanese Prints of the Floating World _______________________ An Honors College Project Presented to the Faculty of the Undergraduate College of Visual and Performing Arts James Madison University _______________________ by Madison Britnell Dalton Accepted by the faculty of the Madison Art Collection, James Madison University, in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Honors College. FACULTY COMMITTEE: HONORS COLLEGE APPROVAL: Project Advisor: Virginia Soenksen, Bradley R. Newcomer, Ph.D., Director, Madison Art Collection and Lisanby Dean, Honors College Museum Reader: Hu, Yongguang Associate Professor, Department of History Reader: Tanaka, Kimiko Associate Professor, Department of Sociology Reader: , , PUBLIC PRESENTATION This work is accepted for presentation, in part or in full, at Honors Symposium on April 3, 2020. -

Object Labels

OBJECT LABELS CONTEMPLATIVE SPACE SECTION 4 SECTION 3 SECTION 1 SECTION 2 PLAN OF THE GALLERY SECTION 1 Travel Utagawa Toyokuni I The peak of Mt Fuji and procession of beauties around 1810 Women and children walk in what’s probably a wedding procession for a princess. Two women leading carry trunks covered with the character kotobuki (“happiness”). The inscription at top right reads “a procession of beauties with Fuji-foreheads”. Fuji-forehead refers to a graceful hairline shaped like Mount Fuji. This used to be a symbol of beauty. Cat. 1 Katsushika Hokusai Shinagawa 1801–04 This location overlooking Edo Bay was a popular spot for viewing the moon. This is Shinagawa, first post town on the Tōkaidō out of Edo City. The woman on the bench wears an agebōshi (cloth headgear to protect the hair from dirt and dust); an ox rests from pulling a cart. While travelling, heavy luggage could be deposited with handlers who would transport it via ox carts. Cat. 2 Katsushika Hokusai Fuji view plain in Owari province Thirty-six Views of Mount Fuji around 1831 Hokusai searched for subjects that would produce an unusual effect when combined with the image of Mt Fuji. This print is one of his most iconic works in the series, which depicts the mountain from various locations in Japan. Owari is one of the western-most places from which Fuji is visible. The great symbol of eternity is amusingly reduced to a tiny triangle set within a large bottomless barrel. By framing Fuji like this, Hokusai creates an intimate dialogue between the iconic mountain and the sinewy man. -

B U L L E T I N

THE SMART MUSEUM OF ART BULLETIN 1990-1991 1991-1992 THE DAVID AND ALFRED SMART MUSEUM OF ART THE UNIVERSITY OF CHICAGO THE SMART MUSEUM OF ART B U L L E T I N 1990-1991 1991-1992 THE DAVID AND ALFRED SMART MUSEUM OF ART THE UNIVERSITY OF CHICAGO CONTENTS Volume 3, 1990-1991, 1991-1992. STUDIES IN THE PERMANENT COLLECTION Copyright © 1992 by The David and Alfred Smart Museum of Art, The University of Chicago, Sectionalism at Work: Construction and Decoration Systems in Ancient Chinese 5550 South Greenwood Avenue, Ritual Vessels 2 Chicago, Illinois, 60637. All rights reserved. ISSN: 1041-6005 Robert J. Poor Three Rare Poetic Images from Japan 18 Louise E. Virgin Photography Credits: Pages 3-14, figs. 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, Jerry Kobyleky Museum Photography; figs, la, 2a, 3a, 5a-f, courtesy of Jon Poor / Poor Design, ©1992 Robert Poor. Pages 19-23, figs. 1-3, Jerry Brush and Ink Paintings by Modern Chinese Women Artists in the Kobyleky Museum Photography. Pages 35-46, 51, Jerry Kobyleky Smart Museum Collection 26 Museum Photography. Page 53, Lloyd De Grane. Page 55, Mark Harrie A. Vanderstappen Steinmetz. Page 56, Rachel Lerner. Page 57, John Booz, ©1991. Pages 58, 60, Matthew Gilson, ©1992. Page 61, Lloyd De Grane. Editor: Stephanie D'Alessandro ACTIVITIES AND SUPPORT Design: Joan Sommers Printing: The University of Chicago Printing Department Collections 34 Acquisitions Loans from the Collection Exhibitions and Programs 30 Exhibitions Events Education Publications Sources of Support 63 Grants Contributions Donors to the Collection Lenders to the Collection This issue of the Bulletin, with three articles on and Japanese works of art given in honor of East Asian works of art in the collection of the Professor Vanderstappen by various donors. -

JAPANESE PRINTS FROMTHELEIBERMUSEUM the Judith and Gus Leiber Collection of Japanese Woodblock Prints by E

JAPANESE PRINTS FROMTHELEIBERMUSEUM The Judith and Gus Leiber Collection of Japanese Woodblock Prints by E. Frankel It is my pleasure to be part of this fine exhibition of ukiyo-e prints. Just as everything else that the Leibers have done in their business as well as personal lives, it is tribute to their outstanding dedication to taste and connoisseurship. This collection has been put together over the last fifty years primarily in New York City.The Leibers have had the same fascination with Japanese woodblock prints shown by such great artistic talents asVincent van Gogh, James Abbott McNeilWhistler, Claude Monet, Edgar Degas, Mary Cassett, Henri deToulouse-Lautrec, Frank Lloyd Wright and James Mitchner. In France this influence has been called Japonisme, which started with the frenzy to collect Japanese art, particularly woodblock print art (ukiyo-e). The woodblock prints from Japan were among the first art of Asia to strongly influence the West.These works were seen in Paris in approximately 1856 and their influence manifested itself in Art Nouveau and French Impressionism.The French artist Félix Bracquemond first came across a copy of the sketchbook Hokusai Manga at the workshop of his printer; the woodblocks had been used as packaging for a consignment of porcelain from Japan. In 1860 and 1861 reproductions (in black and white) of ukiyo-e were published in books on Japan. In 1861 Baudelaire wrote in a letter:“Quite a while ago I received a packet of japonneries. I’ve split them up among my friends.” The following year La Porte Chinoise, a shop selling various Japanese goods including prints, opened in the rue de Rivoli, the most fashionable shopping street in Paris. -

Rising Sun at Te Papa: the Heriot Collection of Japanese Art David Bell* and Mark Stocker**

Tuhinga 29: 50–76 Copyright © Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa (2018) Rising sun at Te Papa: the Heriot collection of Japanese art David Bell* and Mark Stocker** * University of Otago College of Education, PO Box 56, Dunedin, New Zealand ([email protected]) ** Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa, PO Box 467, Wellington, New Zealand ([email protected]) ABSTRACT: In 2016, the Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa (Te Papa) acquired more than 60 Japanese artworks from the private collection of Ian and Mary Heriot. The works make a significant addition to the graphic art collections of the national museum. Their variety and quality offer a representative overview of the art of the Japanese woodblock print, and potentially illustrate the impact of Japanese arts on those of New Zealand in appropriately conceived curatorial projects. Additionally, they inform fresh perspectives on New Zealand collecting interests during the last 40 years. After a discussion of the history and motivations behind the collection, this article introduces a representative selection of these works, arranged according to the conventional subject categories popular with nineteenth- and early twentieth-century Japanese audiences. Bijin-ga pictures of beautiful women, genre scenes and kabuki-e popular theatre prints reflect the hedonistic re-creations of ukiyo ‘floating world’ sensibilities in the crowded streets of Edo. Kachöga ‘bird and flower pictures’ and fukeiga landscapes convey Japanese sensitivities to the natural world. Exquisitely printed surimono limited editions demonstrate literati tastes for refined poetic elegance, and shin-hanga ‘new prints’ reflect changes in sensibility through Japan’s great period of modernisation.