Nora Marks Dauenhauer, Juneau

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

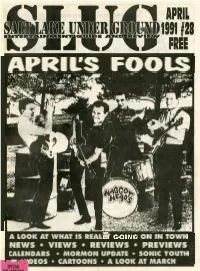

April's Fools

APRIL'S FOOLS ' A LOOK AT WHAT IS REAL f ( i ON IN. TOWN NEWS VIEWS . REVIEWS PREVIEWS CALENDARS MORMON UPDATE SONIC YOUTH -"'DEOS CARTOONS A LOOK AT MARCH frlday, april5 $7 NOMEANSNO, vlcnms FAMILYI POWERSLAVI saturday, april 6 $5 an 1 1 piece ska bcnd from cdlfomb SPECKS witb SWlM HERSCHEL SWIM & sunday,aprll7 $5 from washln on d.c. m JAWBO%, THE STENCH wednesday, aprl10 KRWTOR, BLITZPEER, MMGOTH tMets $10raunch, hemmetal shoD I SUNDAY. APRIL 7 I INgTtD, REALITY, S- saturday. aprll $5 -1 - from bs aqdes, califomla HARUM SCAIUM, MAG&EADS,;~ monday. aprlll5 free 4-8. MAtERldl ISSUE, IDAHO SYNDROME wedn apri 17 $5 DO^ MEAN MAYBE, SPOT fiday. am 19 $4 STILL UFEI ALCOHOL DEATH saturday, april20 $4 SHADOWPLAY gooah TBA mday, 26 Ih. rlrdwuhr tour from a land N~AWDEATH, ~O~LESH;NOCTURNUS tickets $10 heavy metal shop, raunch MATERIAL ISSUE I -PRIL 15 I comina in mayP8 TFL, TREE PEOPLE, SLaM SUZANNE, ALL, UFT INSANE WARLOCK PINCHERS, MORE MONDAY, APRIL 29 I DEAR DICKHEADS k My fellow Americans, though:~eopledo jump around and just as innowtiwe, do your thing let and CLIJG ~~t of a to NW slam like they're at a punk show. otherf do theirs, you sounded almost as ENTEIWAINMENT man for hispoeitivereviewof SWIM Unfortunately in Utah, people seem kd as L.L. "Cwl Guy" Smith. If you. GUIIBE ANIB HERSCHELSWIMsdebutecassette. to think that if the music is fast, you are that serious, I imagine we will see I'mnotamemberofthebancljustan have to slam, but we're doing our you and your clan at The Specks on IMVIEW avid ska fan, and it's nice to know best to teach the kids to skank cor- Sahcr+nightgiwingskrmkin'Jessom. -

ISSUE 1820 AUGUST 17, 1990 BREATHE "Say Aprayer"9-4: - the New Single

ISSUE 1820 AUGUST 17, 1990 BREATHE "say aprayer"9-4: - the new single. Your prayers are answered. Breathe's gold debut album All That Jazz delivered three Top 10 singles, two #1 AC tracks, and songwriters David Glasper and Marcus Lillington jumped onto Billboard's list of Top Songwriters of 1989. "Say A Prayer" is the first single from Breathe's much -anticipated new album Peace Of Mind. Produced by Bob Sargeant and Breathe Mixed by Julian Mendelsohn Additional Production and Remix by Daniel Abraham for White Falcon Productions Management: Jonny Too Bad and Paul King RECORDS I990 A&M Record, loc. All rights reserved_ the GAVIN REPORT GAVIN AT A GLANCE * Indicates Tie MOST ADDED MOST ADDED MOST ADDED MOST ADDED MICHAEL BOLTON JOHNNY GILL MICHAEL BOLTON MATRACA BERG Georgia On My Mind (Columbia) Fairweather Friend (Motown) Georgia On My Mind (Columbia) The Things You Left Undone (RCA) BREATHE QUINCY JONES featuring SIEDAH M.C. HAMMER MARTY STUART Say A Prayer (A&M) GARRETT Have You Seen Her (Capitol) Western Girls (MCA) LISA STANSFIELD I Don't Go For That ((west/ BASIA HANK WILLIAMS, JR. This Is The Right Time (Arista) Warner Bros.) Until You Come Back To Me (Epic) Man To Man (Warner Bros./Curb) TRACIE SPENCER Save Your Love (Capitol) RECORD TO WATCH RECORD TO WATCH RECORD TO WATCH RECORD TO WATCH RIGHTEOUS BROTHERS SAMUELLE M.C. HAMMER MARTY STUART Unchained Melody (Verve/Polydor) So You Like What You See (Atlantic) Have You Seen Her (Capitol) Western Girls (MCA) 1IrPHIL COLLINS PEBBLES ePHIL COLLINS goGARTH BROOKS Something Happened 1 -

“Carried in the Arms of Standing Waves:” the Transmotional Aesthetics of Nora Marks Dauenhauer1

Transmotion Vol 1, No 2 (2015) “Carried in the Arms of Standing Waves:” The Transmotional Aesthetics of Nora Marks Dauenhauer1 BILLY J. STRATTON In October 2012 Nora Marks Dauenhauer was selected for a two-year term as Alaska State Writer Laureate in recognition of her tireless efforts in preserving Tlingit language and culture, as well as her creative contributions to the state’s literary heritage. A widely anthologized author of stories, plays and poetry, Dauenhauer has published two books, The Droning Shaman (1988) and Life Woven With Song (2000). Despite these contributions to the ever-growing body of native American literary discourse her work has been overlooked by scholars of indigenous/native literature.2 The purpose of the present study is to bring attention to Dauenhauer’s significant efforts in promoting Tlingit peoplehood and cultural survivance through her writing, which also offers a unique example of transpacific discourse through its emphasis on sites of dynamic symmetry between Tlingit and Japanese Zen aesthetics. While Dauenhauer’s poesis is firmly grounded in Tlingit knowledge and experience, her creative work is also notable for the way it negotiates Tlingit cultural adaptation in response to colonial oppression and societal disruption through the inclusion of references to modern practices and technologies framed within an adaptive socio-historical context. Through literary interventions on topics such as land loss, environmental issues, and the social and political status of Tlingit people within the dominant Euro-American culture, as well as poems about specific family members, Dauenhauer merges the individual and the communal to highlight what the White Earth Nation of Anishinaabeg novelist, poet and philosopher, Gerald Vizenor, conceives as native cultural survivance.3 She demonstrates her commitment to “documenting Tlingit language and oral tradition” in her role as co-editor, along with her husband, Richard, of the acclaimed series: Classics of Tlingit Oral Literature (47). -

1 United States District Court Southern District of New

Case 1:16-cv-08896-PGG Document 1 Filed 11/16/16 Page 1 of 27 UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT SOUTHERN DISTRICT OF NEW YORK ERIC MCNATT, Plaintiff, v. COMPLAINT RICHARD PRINCE, BLUM & POE, LLC, BLUM & POE NEW YORK, LLC and JURY TRIAL DEMANDED OCULA LIMITED, Defendants. Plaintiff Eric McNatt (“Mr. McNatt” or “Plaintiff”), by and through his undersigned counsel, for his Complaint (“Complaint”) against defendants Richard Prince (“Mr. Prince”), Blum & Poe, LLC and Blum & Poe New York, LLC (each entity individually or both entities collectively, “Blum & Poe”), and Ocula Limited (“Ocula”) (collectively, “Defendants”) hereby alleges as follows: Nature of Action 1. This is an action for injunctive, monetary and declaratory relief arising from Defendants’ infringement of Mr. McNatt’s exclusive rights in the photographic work entitled “Kim Gordon 1” (the “Copyrighted Photograph”, a copy of which is attached hereto as Exhibit A). 2. Mr. McNatt is a practiced and acclaimed commercial, editorial and fine art photographer who is the author and copyright owner of the Copyrighted Photograph, which is a black and white portrait capturing the musician Kim Gordon in her home in Northampton, Massachusetts. 1 Case 1:16-cv-08896-PGG Document 1 Filed 11/16/16 Page 2 of 27 3. Defendant Prince, an “appropriation artist” notorious for incorporating the works of others into artworks for which he claims sole authorship, willfully and knowingly and without seeking or receiving permission from Mr. McNatt, copied and reproduced the Copyrighted Photograph as it appeared on an Internet website. Mr. Prince uploaded a digital copy of the Copyrighted Photograph to the social media website Instagram (“Instagram”) using his own Instagram account, accompanied by three captions (the “Infringing Post”). -

College Voice Vol. 95 No. 5

Connecticut College Digital Commons @ Connecticut College 2011-2012 Student Newspapers 10-31-2011 College Voice Vol. 95 No. 5 Connecticut College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.conncoll.edu/ccnews_2011_2012 Recommended Citation Connecticut College, "College Voice Vol. 95 No. 5" (2011). 2011-2012. 15. https://digitalcommons.conncoll.edu/ccnews_2011_2012/15 This Newspaper is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Newspapers at Digital Commons @ Connecticut College. It has been accepted for inclusion in 2011-2012 by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ Connecticut College. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The views expressed in this paper are solely those of the author. ----- - -- -- ~-- ----. -- - - - GOBER 31 2011 VOllJiVlE XCI . ISSUE5 NEW LONDON. CONNEOK:UT Bieber Fever Strikes Again HEATHER HOLMES Biebs the pass because "Mistle- sian to sit down and listen to his 2009. In the course of two years, and will release his forthcom- Christmas album is that Bieber STAFF WRITER toe" is seriously catchy. music in earnest. This, I now re- the now 17-year-old released his ing album, Under the Mistletoe released his first single from Under the Mistletoe, aptly titled Unlike many of Bieber's big- Before this week, 1 had never alize, was a pretty gigantic mis- Iirst EP, My World (platinum in (which will likely go platinum), "Mistletoe," in mid-October. gest hits, it's the verses rather listened to Justin Bieber. Of take. I'm currently making up the U.S.), his first full-length al- on November 1. than the chorus on "Mistletoe" course, I had heard his biggest for lost time. -

Honouring Indigenous Writers

Beth Brant/Degonwadonti Bay of Quinte Mohawk Patricia Grace Ngati Toa, Ngati Raukawa, and Te Ati Awa Māori Will Rogers Cherokee Nation Cheryl Savageau Abenaki Queen Lili’uokalani Kanaka Maoli Ray Young Bear Meskwaki Gloria Anzaldúa Chicana Linda Hogan Chickasaw David Cusick Tuscarora Layli Long Soldier Oglala Lakota Bertrand N.O. Walker/Hen-Toh Wyandot Billy-Ray Belcourt Driftpile Cree Nation Louis Owens Choctaw/Cherokee Janet Campbell Hale Coeur d’Alene/Kootenay Tony Birch Koori Molly Spotted Elk Penobscot Elizabeth LaPensée Anishinaabe/Métis/Irish D’Arcy McNickle Flathead/Cree-Métis Gwen Benaway Anishinaabe/Cherokee/Métis Ambelin Kwaymullina Palyku Zitkala-Ša/Gertrude Bonnin Yankton Sioux Nora Marks Dauenhauer Tlingit Gogisgi/Carroll Arnett Cherokee Keri Hulme Kai Tahu Māori Bamewawagezhikaquay/Jane Johnston Schoolcraft Ojibway Rachel Qitsualik Inuit/Scottish/Cree Louis Riel Métis Wendy Rose Hopi/Miwok Mourning Dove/Christine Quintasket Okanagan Elias Boudinot Cherokee Nation Sarah Biscarra-Dilley Barbareno Chumash/Yaqui Kateri Akiwenzie-Damm Anishinaabe Dr. Charles Alexander Eastman/ Ohíye S’a Santee Dakota Witi Ihimaera Māori Esther Berlin Diné Lynn Riggs Cherokee Nation Arigon Starr Kickapoo Dr. Carlos Montezuma/Wassaja Yavapai Marilyn Dumont Cree/Métis Woodrow Wilson Rawls Cherokee Nation Ella Cara Deloria/Aŋpétu Wašté Wiŋ Yankton Dakota LeAnne Howe Choctaw Nation Simon Pokagon Potawatomi Marie Annharte Baker Anishinaabe John Joseph Mathews Osage Gloria Bird Spokane Sherwin Bitsui Diné George Copway/Kahgegagahbowh Mississauga Chantal -

Drinking Your Way Through the First Coast St

drinking guide 2007 drinking your way through the first coast st. johns town center phase two | ragtime restaurant review | polyphonic spree interview | brittni wood solo exhibit free weekly guide to entertainment and more | november 8-14, 2007 | www.eujacksonville.com 2 november 8-14, 2007 | entertaining u newspaper COVER PHOTO BY ERIN THURSBY, TAKEN AT TWISTED MARTINI table of contents feature Sea & Sky Spectacular ..........................................................................................................PAGE 13 Town Center - Phase 2 ..........................................................................................................PAGE 14 Town Center - restaurants .....................................................................................................PAGE 15 Cafe Eleven Big Trunk Show ..................................................................................................PAGE 16 Drinking Guide .............................................................................................................. PAGES 20-23 movies Movies in Theaters this Week ............................................................................................ PAGES 6-8 Martian Child (movie review) ...................................................................................................PAGE 6 Fred Claus (movie review) .......................................................................................................PAGE 7 P2 (movie review) ...................................................................................................................PAGE -

American Book Awards 2004

BEFORE COLUMBUS FOUNDATION PRESENTS THE AMERICAN BOOK AWARDS 2004 America was intended to be a place where freedom from discrimination was the means by which equality was achieved. Today, American culture THE is the most diverse ever on the face of this earth. Recognizing literary excel- lence demands a panoramic perspective. A narrow view strictly to the mainstream ignores all the tributaries that feed it. American literature is AMERICAN not one tradition but all traditions. From those who have been here for thousands of years to the most recent immigrants, we are all contributing to American culture. We are all being translated into a new language. BOOK Everyone should know by now that Columbus did not “discover” America. Rather, we are all still discovering America—and we must continue to do AWARDS so. The Before Columbus Foundation was founded in 1976 as a nonprofit educational and service organization dedicated to the promotion and dissemination of contemporary American multicultural literature. The goals of BCF are to provide recognition and a wider audience for the wealth of cultural and ethnic diversity that constitutes American writing. BCF has always employed the term “multicultural” not as a description of an aspect of American literature, but as a definition of all American litera- ture. BCF believes that the ingredients of America’s so-called “melting pot” are not only distinct, but integral to the unique constitution of American Culture—the whole comprises the parts. In 1978, the Board of Directors of BCF (authors, editors, and publishers representing the multicultural diversity of American Literature) decided that one of its programs should be a book award that would, for the first time, respect and honor excellence in American literature without restric- tion or bias with regard to race, sex, creed, cultural origin, size of press or ad budget, or even genre. -

Sealaska Heritage Institute Publications

Sealaska Heritage Institute Publications Summer/Fall 2020 About Sealaska Heritage Institute SEALASKA HERITAGE INSTITUTE is a private exhibits to help the public learn more about nonprofit founded in 1980 to perpetuate and Southeast Alaska Native cultures. enhance Tlingit, Haida, and Tsimshian cultures of SHI has a robust publications arm which produces Southeast Alaska. Its goal is to promote cultural books and scholarly reports on Tlingit, Haida, and diversity and cross-cultural understanding through Tsimshian cultures, art, and languages, as well as public services and events. children’s books. Sealaska Heritage also conducts social, scientific, • Culture: Cultural resources include the and public policy research that promotes Alaska award-winning, four volume Classics of Tlingit Native arts, cultures, history, and education Oral Literature series by Nora and Richard statewide. The institute is governed by a Board of Dauenhauer and SHI’s Box of Knowledge series. Trustees and guided by a Council of Traditional Scholars, a Native Artist Committee, and a • Art: Art-related titles include SHI’s Tlingit Southeast Regional Language Committee. wood carving series and a formline textbook. We offer numerous programs promoting • Language: Texts include the most Southeast Alaskan Native culture, including comprehensive dictionaries ever published for language and art. We maintain a substantial archive the languages, available in book form or as free of Southeast Alaskan Native ethnographic material. PDFs. We partner with local schools to promote • Children’s books: SHI’s Baby Raven Reads academics and cultural education. Biennially, we series offers culturally-based books for produce Celebration, Alaska’s second-largest children up to age 5. Native gathering. -

Sonic Youth Starpower Mp3, Flac, Wma

Sonic Youth Starpower mp3, flac, wma DOWNLOAD LINKS (Clickable) Genre: Rock Album: Starpower Country: US Released: 1991 Style: Alternative Rock, Indie Rock MP3 version RAR size: 1887 mb FLAC version RAR size: 1149 mb WMA version RAR size: 1745 mb Rating: 4.7 Votes: 332 Other Formats: MMF MP4 ASF AC3 MIDI FLAC VOX Tracklist Hide Credits A Starpower (Edit) 2:50 Bubblegum B1 2:45 Bass – Mike WattWritten-By – Kim Fowley, Marty Cert* B2 Expressway (Edit) 4:30 Companies, etc. Phonographic Copyright (p) – SST Records Copyright (c) – Savage Conquest Music Copyright (c) – Kim Fowley Music Mastered At – K Disc Mastering Mastered At – Greg Lee Processing – L-37312 Pressed By – Rainbo Records – S-24767 Pressed By – Rainbo Records – S-24768 Credits Mastered By – JG* Photography By [Photos] – Lazy Eight, Lee* Words By, Music By – Sonic Youth Notes ℗ 1986 SST Records, P.O. Box 1 Lawndale, CA 90260 © 1986 Savage Conquest (ASCAP) (except "Bubblegum" Cert + Fowley, Kim Fowley Music (BMI)) Barcode and Other Identifiers Barcode: 0 18861-0909-1 7 Matrix / Runout (Etchings side A): SST-909-A S-24767 kdisc JG L-37312 Matrix / Runout (Etchings side B): SST-909-B S-24768 kdisc JG L-37312X Rights Society: ASCAP Rights Society: BMI Other versions Category Artist Title (Format) Label Category Country Year SST 080 Sonic Youth Starpower (12", Single) SST Records SST 080 US 1986 SST 909 Sonic Youth Starpower (10", Single, Bro) SST Records SST 909 US 1991 BFFP 7 Sonic Youth Starpower (7", Ltd) Blast First BFFP 7 UK 1986 BFFP7 Sonic Youth Starpower (7", Single) Blast First BFFP7 UK 1986 SST 909 Sonic Youth Starpower (10", Single, Gra) SST Records SST 909 US 1991 Related Music albums to Starpower by Sonic Youth Starpower - Stargirl A Host Of Stars - I't OK To Say No! Dinosaur Jr. -

Universitatea Din Bucureşti Facultatea De Limbi Şi Literaturi Străine Asociaţia Slaviştilor Din România

Romanoslavica vol. XLVII nr.1 UNIVERSITATEA DIN BUCUREŞTI FACULTATEA DE LIMBI ŞI LITERATURI STRĂINE ASOCIAŢIA SLAVIŞTILOR DIN ROMÂNIA Catedra de limbi slave Catedra de filologie rusă ROMANOSLAVICA Vol. XLVII nr.1 Volum dedicat celei de-a 75-a aniversări a profesorului Dorin Gămulescu Editura Universităţii din Bucureşti 2011 1 Romanoslavica vol. XLVII nr.1 Referenŝi ştiinŝifici: prof.dr. Anca Irina Ionescu conf.dr. Mariana Mangiulea Redactori responsabili: prof.dr. Octavia Nedelcu, lect.dr. Anca-Maria Bercaru COLEGIUL DE REDACŜIE: Prof.dr. Constantin Geambaşu, prof.dr. Mihai Mitu, conf.dr. Mariana Mangiulea, Prof.dr. Antoaneta Olteanu COMITETUL DE REDACŜIE: Acad. Gheorghe Mihăilă, membru al Academiei Române, prof.dr. Virgil Şoptereanu, cercet.dr. Irina Sedakova (Institutul de Slavistică şi Balcanistică, Moscova), prof.dr. Mieczysław Dąbrowski (Universitatea din Varşovia), prof.dr. Panaiot Karaghiozov (Universitatea „Kliment Ohridski‖, Sofia), conf.dr. Antoni Moisei (Universitatea din Cernăuŝi), prof.dr. Corneliu Barborică, prof.dr. Dorin Gămulescu, prof.dr. Jiva Milin, prof.dr. Ion Petrică, prof.dr. Onufrie Vinŝeler, asist. Camelia Dinu (secretar de redacŝie) (Tehno)redactare: prof.dr. Antoaneta Olteanu © Asociaŝia Slaviştilor din România (Romanian Association of Slavic Studies) [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] IMPORTANT: Materialele nepublicate nu se înapoiază. ISSN 0557-272X 2 Romanoslavica vol. XLVII nr.1 PROFESORUL DORIN GĂMULESCU LA A 75-a ANIVERSARE 3 Romanoslavica vol. XLVII nr.1 4 Romanoslavica vol. -

SPARTAN DAILY Vol

It's all in the wrist A dance extravaganza Spring practice begins A tournament of the unusual sport Frisbee golf The University Theatre hosts a collection Coming off a Cal Bowl victory the football invades Santa Cruz this weekend of dances performed by SJSU students team brings optimism to spring practice See CenterStage inside Page 4 See CenterStage inside SPARTAN DAILY Vol. 96, No. 46 Published for San Jose State University since 1934 Thursday, April 11, 1991 UPD detains three protesters Registration By Brooke Shelby Biggs Daily staff writer Three students were temporari- ly detained by University Police for on suspicion of vandalism after delayed attempting to fly the gay -pride rainbow flag on the flagpole behind MacQuarrie Hall Wednes- day. Byl Hulse, Mike Kemmerer fall semester and lbd Comerford, a gay ROTC By Carolyn Swaggart poned is that officials within Aca- alumnus and Navy veteran, were Daily stall writer demic Affairs and Admissions and part of a protest against the cam- The schedule of Fall 1991 class- Records were hoping to get better pus ROTC compliance with a es will not go on sale for students information at the March trustees' Department of Defense policy until May 15 the delay a result meeting. Robinson said. that bars gays from joining the of budget cuts that will eliminate "And indeed, we got some con- military. 640 classes next fall. firmation of what we knew earlier, The protest was a part of the Admissions and Records and the and enough information to allow National Day of Action against Academic Affairs Vice-President's us to proceed to make a budget ROTC which was sponsored by Office were asked to postpone the allocation, so that the schools and the American Civil Liberties schedules until departments could departments would have an Union.