Uva-DARE (Digital Academic Repository)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Status and Protection of Globally Threatened Species in the Caucasus

STATUS AND PROTECTION OF GLOBALLY THREATENED SPECIES IN THE CAUCASUS CEPF Biodiversity Investments in the Caucasus Hotspot 2004-2009 Edited by Nugzar Zazanashvili and David Mallon Tbilisi 2009 The contents of this book do not necessarily reflect the views or policies of CEPF, WWF, or their sponsoring organizations. Neither the CEPF, WWF nor any other entities thereof, assumes any legal liability or responsibility for the accuracy, completeness, or usefulness of any information, product or process disclosed in this book. Citation: Zazanashvili, N. and Mallon, D. (Editors) 2009. Status and Protection of Globally Threatened Species in the Caucasus. Tbilisi: CEPF, WWF. Contour Ltd., 232 pp. ISBN 978-9941-0-2203-6 Design and printing Contour Ltd. 8, Kargareteli st., 0164 Tbilisi, Georgia December 2009 The Critical Ecosystem Partnership Fund (CEPF) is a joint initiative of l’Agence Française de Développement, Conservation International, the Global Environment Facility, the Government of Japan, the MacArthur Foundation and the World Bank. This book shows the effort of the Caucasus NGOs, experts, scientific institutions and governmental agencies for conserving globally threatened species in the Caucasus: CEPF investments in the region made it possible for the first time to carry out simultaneous assessments of species’ populations at national and regional scales, setting up strategies and developing action plans for their survival, as well as implementation of some urgent conservation measures. Contents Foreword 7 Acknowledgments 8 Introduction CEPF Investment in the Caucasus Hotspot A. W. Tordoff, N. Zazanashvili, M. Bitsadze, K. Manvelyan, E. Askerov, V. Krever, S. Kalem, B. Avcioglu, S. Galstyan and R. Mnatsekanov 9 The Caucasus Hotspot N. -

Georgia, Adjara Autonomous Republic

Georgia, Ajara Autonomous Republic: Ajara Solid Waste Management Project Stakeholder Engagement Plan (SEP) April 2015 Rev May 2015 1 List of abbreviations EBRD European Bank for Reconstruction and Development EHS Environmental health and safety ESAP Environmental and Social Action Plan ESIA Environmental and Social Impact Assessment EU European Union GHG Greenhouse Gas (e.g. methane, carbon dioxide and other gases) Ha hectare HH Households HR Human resources Km kilometer R/LRF Resettlement/Livelihood Restauration Framework M meter MIS Management Information System MoFE Ministry of Finance and Economy of Ajara OHS Occupational Health and safety PAP Project affected people PR Performance Requirement RAP Resettlement Action Plan SEP Stakeholder Engagement Plan SWC Solid Waste Company SWM Solid Waste Management ToR Terms of Reference 2 Table of Contents 1 Introduction ............................................................................................................................ 4 2 Brief Project Description .................................................................................................... 4 2.1 Closure of Batumi and Kobuleti ............................................................................................. 5 2.2 Construction of Tsetskhlauri landfill ................................................................................... 5 2.3 Organisation .................................................................................................................................. 7 3 Applicable Regulations -

Wikivoyage Georgia.Pdf

WikiVoyage Georgia March 2016 Contents 1 Georgia (country) 1 1.1 Regions ................................................ 1 1.2 Cities ................................................. 1 1.3 Other destinations ........................................... 1 1.4 Understand .............................................. 2 1.4.1 People ............................................. 3 1.5 Get in ................................................. 3 1.5.1 Visas ............................................. 3 1.5.2 By plane ............................................ 4 1.5.3 By bus ............................................. 4 1.5.4 By minibus .......................................... 4 1.5.5 By car ............................................. 4 1.5.6 By train ............................................ 5 1.5.7 By boat ............................................ 5 1.6 Get around ............................................... 5 1.6.1 Taxi .............................................. 5 1.6.2 Minibus ............................................ 5 1.6.3 By train ............................................ 5 1.6.4 By bike ............................................ 5 1.6.5 City Bus ............................................ 5 1.6.6 Mountain Travel ....................................... 6 1.7 Talk .................................................. 6 1.8 See ................................................... 6 1.9 Do ................................................... 7 1.10 Buy .................................................. 7 1.10.1 -

Status and Protection of Globally Threatened Species in the Caucasus

STATUS AND PROTECTION OF GLOBALLY THREATENED SPECIES IN THE CAUCASUS CEPF Biodiversity Investments in the Caucasus Hotspot 2004-2009 Edited by Nugzar Zazanashvili and David Mallon Tbilisi 2009 The contents of this book do not necessarily re ect the views or policies of CEPF, WWF, or their sponsoring organizations. Neither the CEPF, WWF nor any other entities thereof, assumes any legal liability or responsibility for the accuracy, completeness, or usefulness of any information, product or process disclosed in this book. Citation: Zazanashvili, N. and Mallon, D. (Editors) 2009. Status and Protection of Globally Threatened Species in the Caucasus. Tbilisi: CEPF, WWF. Contour Ltd., 232 pp. ISBN 978-9941-0-2203-6 Design and printing Contour Ltd. 8, Kargareteli st., 0164 Tbilisi, Georgia December 2009 The Critical Ecosystem Partnership Fund (CEPF) is a joint initiative of l’Agence Française de Développement, Conservation International, the Global Environment Facility, the Government of Japan, the MacArthur Foundation and the World Bank. This book shows the effort of the Caucasus NGOs, experts, scienti c institutions and governmental agencies for conserving globally threatened species in the Caucasus: CEPF investments in the region made it possible for the rst time to carry out simultaneous assessments of species’ populations at national and regional scales, setting up strategies and developing action plans for their survival, as well as implementation of some urgent conservation measures. Contents Foreword 7 Acknowledgments 8 Introduction CEPF Investment in the Caucasus Hotspot A. W. Tordoff, N. Zazanashvili, M. Bitsadze, K. Manvelyan, E. Askerov, V. Krever, S. Kalem, B. Avcioglu, S. Galstyan and R. Mnatsekanov 9 The Caucasus Hotspot N. -

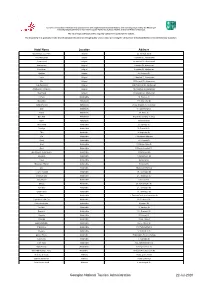

LEPL Tbilisi State Medical University First University Clinic Tbilisi Gudamakari St

LEPL Tbilisi State Medical University First University Clinic Tbilisi Gudamakari st. N4 Aversi Clinic Ltd Tbilisi Vazha-Pshavela Ave. N27 b Neolab Ltd Tbilisi Tashkent st. N47 New Hospitals Ltd Tbilisi Krtsanisi st. N12 Medical Center "Cito" Tbilisi Paliashvili st. N40 Molecular Diagnostics Centre Tbilisi Lubliana st. N11 A Megalab Tbilisi Kavtaradze st. N23 Infections Diseases, Aids And Clinical Immunology Research Center Tbilisi Al. Kazbegi st. N16 Med Diagnostics Tbilisi A. Beliashvili N78 National Tuberculosis Center Tbilisi Adjara st. N8, 0101 State Laboratory of Agriculture, Tbilisi Zonal Diagnostic Laboratory (ZDL) Tbilisi V. Godziashvili st. N49 Medical World Diagnostics Ltd Tbilisi Lubliana st. N33 "National Genetics Laboratory" GN-Invest Ltd. Tbilisi David Agmashenebeli Ave. N240 Medi Prime Tbilisi Gabriel Salosi st. N9b5 PCR Diagnostic and Research Laboratory - Prime Lab Tbilisi Bokhua st. N11 Genomics Tbilisi Sulkhan Tsintsadze st. N23 Bacteriophage Analytical Diagnostic Center- Diagnose -90 Tbilisi L. Gotua st. N3 Ultramed Tbilisi Ureki st. N15 Medison Holding Tbilisi Gobronidze st. N27 Medison Holding Tbilisi Vazha-Pshavela Ave. 83/11 Medison Holding Tbilisi Kaloubani st. N12 Evex Clinics - Mtatsminda Polyclinic Tbilisi Vekua st. N3 Ltd. "Medcapital" - 1 Tbilisi D. Gamrekeli st. N19 Ltd. MedCapital - 2 Tbilisi Moscow Ave. 4th sq. 3rd quarter Ltd. "Medcapital" - 3 Tbilisi I. Vekua st. N18 "Tbilisi Adult Polyclinic N19" Ltd Tbilisi Moscow Ave. N23 JSC Evex Clinics - Didube Polyclinic Tbilisi Akaki Tsereteli Ave. N123 JSC Evex Clinics - Varketili Polyclinic Tbilisi Javakheti st. N30 JSC Evex Clinics - Isani Polyclinic Tbilisi Ketvan Tsamebuli Ave. N69 JSC Evex Clinics - Saburtalo Polyclinic Tbilisi Vazha-Pshvela Ave. N40 Tbilisi Sea Hospital Tbilisi Varketili-3 IV m / r, plot 14/430 "St. -

Gender and Society: Georgia

Gender and Society: Georgia Tbilisi 2008 The Report was prepared and published within the framework of the UNDP project - “Gender and Politics” The Report was prepared by the Institute for Policy Studies (IPS) The author: Nana Sumbadze For additional information refer to the office of the UNDP project “Gender and Politics” at the following address: Administrative building of the Parliament of Georgia, 8 Rustaveli avenue, room 034, Tbilisi; tel./fax (99532) 923662; www.genderandpolitics.ge and the office of the IPS, Chavchavadze avenue, 10; Tbilisi 0179; tel./fax (99532) 220060; e-mail: [email protected] The views expressed in this publication are those of the author and do not necessarily represent those of the United Nations or UNDP Editing: Sandeep Chakraborty Book design: Gio Sumbadze Copyright © UNDP 2008 All rights reserved Contents Acknowledgements 4 List of abbreviations 5 Preface 6 Chapter 1: Study design 9 Chapter 2: Equality 14 Gender in public realm Chapter 3: Participation in public life 30 Chapter 4: Employment 62 Gender in private realm Chapter 5: Gender in family life 78 Chapter 6: Human and social capital 98 Chapter 7: Steps forward 122 Bibliography 130 Annex I. Photo Voice 136 Annex II. Attitudes of ethnic minorities towards equality 152 Annex III. List of entries on Georgian women in Soviet encyclopaedia 153 Annex IV. List of organizations working on gender issues 162 Annex V. List of interviewed persons 173 Annex VI. List of focus groups 175 Acknowledgements from the Author The author would like to express her sincere gratitude to the staff of UNDP project “Gender and Politics” for their continuous support, and to Gender Equality Advisory Council for their valuable recommendations. -

Causes of War Prospects for Peace

Georgian Orthodox Church Konrad-Adenauer-Stiftung CAUSES OF WAR PROS P E C TS FOR PEA C E Tbilisi, 2009 1 On December 2-3, 2008 the Holy Synod of the Georgian Orthodox Church and the Konrad-Adenauer-Stiftung held a scientific conference on the theme: Causes of War - Prospects for Peace. The main purpose of the conference was to show the essence of the existing conflicts in Georgia and to prepare objective scientific and information basis. This book is a collection of conference reports and discussion materials that on the request of the editorial board has been presented in article format. Publishers: Metropolitan Ananya Japaridze Katia Christina Plate Bidzina Lebanidze Nato Asatiani Editorial board: Archimandrite Adam (Akhaladze), Tamaz Beradze, Rozeta Gujejiani, Roland Topchishvili, Mariam Lordkipanidze, Lela Margiani, Tariel Putkaradze, Bezhan Khorava Reviewers: Zurab Tvalchrelidze Revaz Sherozia Giorgi Cheishvili Otar Janelidze Editorial board wishes to acknowledge the assistance of Irina Bibileishvili, Merab Gvazava, Nia Gogokhia, Ekaterine Dadiani, Zviad Kvilitaia, Giorgi Cheishvili, Kakhaber Tsulaia. ISBN 2345632456 Printed by CGS ltd 2 Preface by His Holiness and Beatitude Catholicos-Patriarch of All Georgia ILIA II; Opening Words to the Conference 5 Preface by Katja Christina Plate, Head of the Regional Office for Political Dialogue in the South Caucasus of the Konrad-Adenauer-Stiftung; Opening Words to the Conference 8 Abkhazia: Historical-Political and Ethnic Processes Tamaz Beradze, Konstantine Topuria, Bezhan Khorava - A -

Guidebook on Legal Immigration Guidebook on Legal Immigration 2015 Author: Secretariat of the State Commission on Migration Issues Address: 67A, A

GUIDEBOOK ON LEGAL IMMIGRATION GUIDEBOOK ON LEGAL IMMIGRATION 2015 Author: Secretariat of the State Commission on Migration Issues Address: 67a, A. Tsereteli ave., Tbilisi 0154 Georgia Tel: +995 322 401 010 Email: [email protected] Website: www.migration.commission.ge STATE COMMISSION ON MIGRATION ISSUES Ministry of Internally Displaced Ministry of Justice Ministryinistry of InternalInternal AffairsAffairs Ministry of Foreign Affairs Persons from the Occupied Territories, Accommodation and Refugees Office of the State Minister for Ministry of Labour, Health and Office of the State Minister for Ministry of Economy and Diaspora Issues Social Affairs European and Euro-Atlantic Sustainable Development Integration Ministry of Finance Ministry of Education and Science National Statistics Office Ministry of Regional Development and Infrastructure The Guidebook has been developed by the Secretariat of the State Commission on Migration Issues. Translated and published within the framework of the EU-funded project “enhancing Georgia’s migration management” (eniGmma) 2 TABLE OF CONTENTS About the Guidebook .......................................................................................................................4 Getting settled in Georgia ................................................................................................................5 Categories and types of Georgian visa ......................................................................................... 11 Who can travel visa-free to Georgia ........................................................................................... -

Full Hotel List (Website PDF)

a List of accommodation facilities that operate in line with implemented recommendations and are being inspected by the Ministry of Internally Displaced Persons from the Occupied Territories, Labour, Heaths and Social Affairs of Georgia. The list of inspected hotels will be regurally updated and posted on the website. Our key priority is to gradually resume tourism alongside the provision of high-quality services while preserving the safety of our destination that has been internationally acclaimed. Hotel Name Location Address Guest House LTD Nike Abasha 92, Tavisupleba St Villa Abastumani Adigeni 5 Asatiani St., Abastumani Green Hotel Adigeni 16 Asatiani Str. Abastumani Abastumani Adigeni 1 Asatiani St. Abastumani New House Adigeni 8 Asatiani St, Abastumani Ojakhuri Adigeni 96 Rustaveli St. Iveria Adigeni 19 Asatiani St. Abastumani Rio Adigeni 35 Rustaveli St. Abastumani 16 G Paliashvili Adigeni 16G Paliashvili St. Abastumani Abastumani Residence Adigeni 10 Paliashvili St Abastumani Hotel David Adigeni 41 Asaatiani St. Abastumani Lomsia Akhaktsikhe 10, Kostava St. Grand Mor Akhalkalaki 11/1 Charentsi St. Vardzia Resort Akhalkalaki Village Gogasheni, Chachkari Idiali Akhalkalaki 46 Tamar Mepe St. Ararat Akhalkalaki 13, Kamo St. Euro Star Akhalkalaki Airport Surrounding Territory Garni Akhalkalaki M.Mashtotsi St New Grand Akhaltsikhe 26 Aspindze St. Prestige Akhaltsikhe 76 Rustaveli St. Tiflis Akhaltsikhe 12 Aspindza St. Rio Akhaltsikhe 1 Akhalkalaki Highway Rabat Akhaltsikhe 58 E.Atoneli St Almi Akhaltsikhe 11 Sulkhan Saba St. Beni Akhaltsikhe 5 Kharistchirashvili St. Guest House Cozy House Akhaltsikhe 33 Gvaramia St. Caucasia Akhaltsikhe 1 Agmashebeli St. Lotus Akhaltsikhe 90 Atoneli St. Millennium Rabati Akhaltsikhe 98 Atoneli St. Like Akhaltsikhe Abastumani Highway Teracce Rabath Akhaltsikhe 18, Tsikhisdziri St. -

Heritage Days

1 October 4 – 6, 2019 European Heritage Days Arts and Entertainment 2 October 4 TBILISI Ilia’s Garden, 73 Agmashenebeli Ave., 20:00. yyOpen air film screening: a silent film by Kote Marjanishvili “Amoki”, accompanied with electronic music October 5 TBILISI Giorgi Leonidze State Museum of Georgian Literature, 8 Chanturia St., Tbilisi, 16:00. yyPublic lecture by art critic Ketevan Shavgulidze: Artists vs Museums IMERETI V. Mayakovsky House Museum, 51 Baghdati Str., Baghdati 15:00. yy“ART-Mayakovsky” – concert, art Exhibition, performance Zestafoni Local History Museum, 25 Agmashenebeli Str., Zestafoni, 13:00. yy“We Paint the World” – exhibition of creative works (paintings, works of applied art) by students of public and private schools of Zestafoni municipality #heritagedays 3 House Museum of Ushangi Chkheidze, 40 Chkheidze Str., Zestafoni 13:00. yy“Velvet Trails” – students of public and private schools of Zestafoni municipality present their works in the courtyard of the museum (poetry and literature readings); Local poets also participate in the event. Surroundings of the White Bridge, Kutaisi, 18:00. yyClassical music concert Veriko’s Square, Kutaisi, 12:00-14:00. yyPhoto exhibition “Kutaisi is a European City”; Photo exhibition “European Champions of Kutaisi”; Procession of the Mask Theater characters; Painting performance by G. Maisuradze Art School students Z. Paliashvili House-Museum, 25 Varlamishvili Str., Kutaisi, 12:00. yyExhibition and lectures on Kutaisi Catholics Center of the Catholic Church, 12 Newport Str., Kutaisi, 20:00. yyFlash mob with the participation of youth and performances of the brass band Local History Museum of Tskaltubo, Rustaveli Str., Tskaltubo, 12:00. yyPhoto exhibition “Georgia’s Way Goes to Europe” yyConference “Georgia and Europe” #heritagedays 4 Surroundings of Tskaltubo Municipal Park, 15:00. -

The Muslim Uprising in Ajara and the Stalinist Revolution in the Periphery

Nationalities Papers The Journal of Nationalism and Ethnicity ISSN: 0090-5992 (Print) 1465-3923 (Online) Journal homepage: http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/cnap20 The Muslim uprising in Ajara and the Stalinist revolution in the periphery Timothy K. Blauvelt & Giorgi Khatiashvili To cite this article: Timothy K. Blauvelt & Giorgi Khatiashvili (2016): The Muslim uprising in Ajara and the Stalinist revolution in the periphery, Nationalities Papers, DOI: 10.1080/00905992.2016.1142521 To link to this article: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/00905992.2016.1142521 Published online: 01 Mar 2016. Submit your article to this journal View related articles View Crossmark data Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at http://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=cnap20 Download by: [Timothy K. Blauvelt] Date: 01 March 2016, At: 22:33 Nationalities Papers, 2016 http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/00905992.2016.1142521 The Muslim uprising in Ajara and the Stalinist revolution in the periphery Timothy K. Blauvelta* and Giorgi Khatiashvilib aCollege of Arts and Sciences, Ilia State University, 3/5 Cholokashvili Ave, Tbilisi 0162, Georgia; bPamplin College of Arts, Humanities, and Social Sciences, Augusta University, 1120 15 St. Augusta, GA 30912, USA (Received 21 May 2015; accepted 20 July 2015) In 1929, local officials in the mountainous region of upper Ajara in the Georgian Soviet Socialist Republic (SSR) pursued aggressive policies to force women to remove their veils and to close religious schools, provoking the Muslim peasant population to rebellion in one of the largest and most violent of such incidents in Soviet history. The central authorities in Moscow authorized the use of Red Army troops to suppress the uprising, but they also reversed the local initiatives and offered the peasants concessions. -

Muslim Minorities of Bulgaria and Georgia: a Comparative Study of Pomaks and Ajarians

MUSLIM MINORITIES OF BULGARIA AND GEORGIA: A COMPARATIVE STUDY OF POMAKS AND AJARIANS A THESIS SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUATE SCHOOL OF SOCIAL SCIENCES OF MIDDLE EAST TECHNICAL UNIVERSITY BY ALTER KAHRAMAN IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR PHILOSOPHY IN THE DEPARTMENT OF AREA STUDIES OCTOBER 2020 Approval of thE thEsis: MUSLIM MINORITIES OF BULGARIA AND GEORGIA: A COMPARATIVE STUDY OF POMAKS AND AJARIANS submittEd by ALTER KAHRAMAN in partial fulfillmEnt of thE rEquirEmEnts for thE degrEE of Doctor of Philosophy in ArEa Studies, thE GraduatE School of Social SciEncEs of MiddlE East TEchnical University by, Prof. Dr. Yaşar KONDAKÇI Dean GraduatE School of Social SciEncEs Assist. Prof. Dr. Derya GÖÇER Head of DEpartmEnt ArEa StudiEs Prof. Dr. AyşEgül AYDINGÜN SupErvisor Sociology Examining CommittEE MEmbErs: Prof. Dr. ÖmEr TURAN (Head of thE Examining CommittEE) MiddlE East TEchnical UnivErsity History Prof. Dr. AyşEgül AYDINGÜN (SupErvisor) MiddlE East TEchnical UnivErsity Sociology Prof. Dr. Pınar KÖKSAL MiddlE East TEchnical UnivErsity Political SciEncE and Public Administration Prof. Dr. Suavi AYDIN HacettEpE UnivErsity Communication SciEncEs Prof. Dr. AyşE KAYAPINAR National DEfEncE UnivErsity History PlAGIARISM I hErEby dEclarE that all information in this documEnt has bEEn obtainEd and prEsEntEd in accordancE with academic rulEs and Ethical conduct. I also declarE that, as rEQuirEd by thesE rulEs and conduct, I havE fully citEd and rEfErEncEd all matErial and rEsults that arE not original to this work. NamE, Last namE: AltEr Kahraman SignaturE: iii ABSTRACT MUSLIM MINORITIES OF BULGARIA AND GEORGIA: A COMPARATIVE STUDY OF POMAKS AND AJARIANS Kahraman, AltEr Ph.D., DEpartmEnt of ArEa StudiEs SupErvisor: Prof.