Men and Masculinities in Nordic Cinema and Its American Remakes: a Comparative Analysis

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Walpole Public Library DVD List A

Walpole Public Library DVD List [Items purchased to present*] Last updated: 9/17/2021 INDEX Note: List does not reflect items lost or removed from collection A B C D E F G H I J K L M N O P Q R S T U V W X Y Z Nonfiction A A A place in the sun AAL Aaltra AAR Aardvark The best of Bud Abbot and Lou Costello : the Franchise Collection, ABB V.1 vol.1 The best of Bud Abbot and Lou Costello : the Franchise Collection, ABB V.2 vol.2 The best of Bud Abbot and Lou Costello : the Franchise Collection, ABB V.3 vol.3 The best of Bud Abbot and Lou Costello : the Franchise Collection, ABB V.4 vol.4 ABE Aberdeen ABO About a boy ABO About Elly ABO About Schmidt ABO About time ABO Above the rim ABR Abraham Lincoln vampire hunter ABS Absolutely anything ABS Absolutely fabulous : the movie ACC Acceptable risk ACC Accepted ACC Accountant, The ACC SER. Accused : series 1 & 2 1 & 2 ACE Ace in the hole ACE Ace Ventura pet detective ACR Across the universe ACT Act of valor ACT Acts of vengeance ADA Adam's apples ADA Adams chronicles, The ADA Adam ADA Adam’s Rib ADA Adaptation ADA Ad Astra ADJ Adjustment Bureau, The *does not reflect missing materials or those being mended Walpole Public Library DVD List [Items purchased to present*] ADM Admission ADO Adopt a highway ADR Adrift ADU Adult world ADV Adventure of Sherlock Holmes’ smarter brother, The ADV The adventures of Baron Munchausen ADV Adverse AEO Aeon Flux AFF SEAS.1 Affair, The : season 1 AFF SEAS.2 Affair, The : season 2 AFF SEAS.3 Affair, The : season 3 AFF SEAS.4 Affair, The : season 4 AFF SEAS.5 Affair, -

Florida Lottery Clinical Studies Show It Even Relieves Pain, Tingling PICK 2 Feb

HIGHLANDS NEWS-SUN Monday, February 11, 2019 VOL. 100 | NO. 042 | $1.00 YOUR HOMETOWN NEWSPAPER SINCE 1919 An Edition Of The Sun APCI hiring process fell short regarding shooter By KIM LEATHERMAN and ALLEN appear to have been a high “The Department checks in accordance with MOODY priority not too long ago, attempts to attain job Florida Statutes.” STAFF WRITERS even by those who had a reference checks on all There are six vested interest in wanting candidates, but it is very “Mandatory” checks SEBRING — Zephen to know more about the common for former required by the Florida Xaver’s background has individual. employers to be unrespon- Department of Law become a focal point for When he applied sive or only respond with Enforcement for new hires: law enforcement, journal- for a job at Avon Park basic information, such Previous Employment; ists and a public struggling Correctional Institution in as dates of employment,” FCIC (Florida Crime to comprehend his actions September 2018, he listed said Patrick Manderfi eld, Information Center) on Jan. 23, when he shot three previous employers. press secretary for the Record; NCIC (National and killed fi ve people The Florida Department Florida Department Crime Information at the Sebring SunTrust of Corrections said it was of Corrections. “The Center) Record; Local Law FLORIDA DEPARTMENT OF CORRECTIONS PHOTO Bank, 1901 U.S. 27 South. unable to reach any of Department conducted But Xaver’s past doesn’t HIRING | 5A A sign at the Avon Park Correctional Institution. them. all required background Don’t be fooled by fake cops Sebring roars to the 20s By KIM LEATHERMAN STAFF WRITER Crowds, fair weather for 36th annual event LAKE PLACID — Most people are taught from the time they are toddlers to respect fi rst respond- ers. -

Responsibility Studio Index

2020 Studio Responsibility Index STUDIO RESPONSIBILITY INDEX 2020 From the Office of the President & CEO, Sarah Kate Ellis GLAAD created the Studio Responsibility Index in Two years ago, GLAAD issued a challenge - 20 2013 to track lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, percent of annual major studios releases must include and queer (LGBTQ) inclusion in major studio films LGBTQ characters by the 2021-year’s end, and that after seeing the progress our TV research had driven 50 percent must include LGBTQ characters by the in the industry and with creators. Entertainment is end of 2024. While the COVID-19 global pandemic America’s most widespread cultural export – reflecting has and will continue to have ripple effects across the the culture that produces it while also having the film business and all businesses, we still believe in this opportunity to shape culture through nuanced and challenge and reaffirm our commitment to holding inclusive storytelling – and wide release major studio the industry accountable for telling inclusive stories. films are marketed to and accessible by billions of Four studios individually hit this 20 percent goal: people across the U.S. and around the world. Yet, Paramount Pictures at 33 percent of their annual slate LGBTQ characters are still often sidelined or entirely including LGBTQ characters, United Artists Releasing excluded from major Hollywood releases. at 29 percent, Lionsgate at 25 percent, and Walt While we have seen consistent forward movement in Disney Studios rounding out at 21 percent – though no LGBTQ representation on television in recent years, studio hit the previous years’ established record high mainstream films continue to lag behind. -

Jessica Reynolds As Audrey Earnshaw

Genre: Horror | Production Year: 2019 | Location: Alberta Release Date: October 6, 2020 Writer/Director: Thomas Robert Lee Producer: Gianna Isabella Executive Producers: Marie-Claude Poulin, James Mahoney, Thomas Robert Lee, Bill Marks, Divya Shahani, George Mihalka, Susan Curran, Patrick Ewald & Shaked Berenson. Production Company: Gate 67 Films Sales Agent: Epic Pictures Group Canadian Distribution: A71 Entertainment, Telefilm Canada & HorizonOne Pictures IMDb Logline A mother & daughter are suspected of witchcraft by their devout rural community. Short Synopsis The Curse of Audrey Earnshawexplores the disturbed bond between Audrey, an enigmatic young woman, and Agatha, her domineering mother, who live secretly as occultists on the outskirts of a remote Protestant village. Following an ominous encounter between Agatha and a grieving townsman, and a rare sighting of Audrey by a local, Agatha’s authority crumbles as Audrey asserts her dominance. Meanwhile, hysteria mounts within the community as a mysterious pestilence spreads throughout the fields and livestock, yet the Earnshaw farm remains strangely unaffected… Set against the autumnal palette of the harvest season in 1973, The Curse of Audrey Earnshaw is a nightmarish descent into the mythic. Director Biography Thomas Robert Lee Thomas Robert Lee is an emerging Canadian filmmaker. His debut featureEmpyrean was independently financed and produced.Empyrean is a science-fiction drama, told in black and white, about a man who experiences a psychic awakening after emerging from a coma. His sophomore feature was The Curse Of Audrey Earnshaw, a folk horror tale about a mother and daughter suspected of witchcraft by their devout rural community. The Curse Of Audrey Earnshaw was produced with the participation of Telefilm Canada. -

Film Schedule Summary Governors Crossing 14 1402 Hurley Drive Report Dates

Film Schedule Summary Governors Crossing 14 1402 Hurley Drive Report Dates: Friday, February 22, 2019 - Thursday, February 28, 2019 Sevierville, TN 37862, (865) 366-1752 ***************************************************************STARTING FRIDAY, FEB 22*************************************************************** FIGHTING WITH MY FAMILY PG13 1 Hours 40 Minutes FRIDAY - WEDNESDAY 12:00 pm 02:20 pm 04:40 pm 07:00 pm 09:20 pm Dwayne Johnson, Florence Pugh, Lena Headey --------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- HOW TO TRAIN YOUR DRAGON: THE HIDDEN WORLD PG 1 Hours 44 Minutes FRIDAY - WEDNESDAY 12:40 pm 01:30 pm 03:10 pm 04:00 pm 06:05 pm 08:30 pm Jonah Hill, Cate Blanchett, Kristen Wiig --------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- RUN THE RACE PG 1 Hours 42 Minutes FRIDAY - WEDNESDAY 12:10 pm 02:30 pm 04:50 pm 07:10 pm 09:30 pm Mykelti Williamson, Frances Fisher, Kristoffer Polaha, Tanner Stine, Evan Hofer, Kelsey Reinhardt --------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- *HOW TO TRAIN YOUR DRAGON: THE HIDDEN WORLD SXS PG 1 Hours 44 Minutes FRIDAY - WEDNESDAY 11:50 am 02:20 pm 04:50 pm 07:20 pm 09:40 pm Jonah Hill, Cate Blanchett, Kristen Wiig --------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- -

Star Channels, August 29

AUGUST 29 - SEPTEMBER 4, 2021 staradvertiser.com MAMA DRAMA While the cast fi gure out their uncomfortable love triangles, we get to watch from a much more comfortable distance when Season 2 of I Love a Mama’s Boy. The show follows couples navigating the relationship between the “boys” and their mothers who just can’t let go. Premiering Sunday, Aug. 29, on TLC. CAMERA & LIGHTING FOR BEGINNERS Learn how to properly set up, light and shoot in the second of three courses taught by ¶Ōlelo’s in-house experts. To sign up, visit olelo.org/training olelo.org Video Production | Camera, Audio & Lighting | Video Editing $75 per class | Just $50 per class if you commit to and complete all 3 classes 590255_TrainingAds_2021_2in_F.indd 2 4/30/21 4:17 PM ON THE COVER | I LOVE A MAMA’S BOY Mommy dearest TLC launches Season 2 relationship — not always accompanied by room relationship, but it didn’t work out that smothering mothers; something the Season way. of “I Love a Mama’s Boy” 2 trailer does a great job of showing. Complete Trying to help in that department, mommy with awkward professions of mother-son love, dearest accompanied Kim to the lingerie sour looks from partners, mothers feeding store to pick out something special for Matt. By Rachel Jones their sons scrambled eggs and mothers insist- Needless to say, shortly thereafter, Matt and TV Media ing on being “honeymoon buddies,” even view- Kim moved out of Kelly’s house and into their ers will want to tell these moms to butt out. -

Jan-Feb 2019

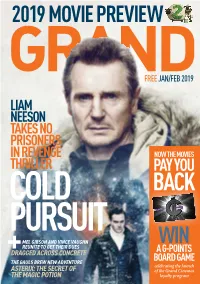

GRAND MAGAZINE 2019 MOVIE PREVIEW JANUARY/FEBRUARY 2019 GRANDFREE JAN/FEB 2019 LIAM NEESON TAKES NO COLD PURSUIT PURSUIT COLD PRISONERS IN REVENGE NOW THE MOVIES THRILLER PAY YOU • 2019 MUST LIST LIST 2019 MUST COLD BACK • G-POINTS LAUNCH PURSUIT MEL GIBSON AND VINCE VAUGHN WIN REUNITE TO GET THEIR DUES A G-POINTS +DRAGGED ACROSS CONCRETE BOARD GAME THE GAULS BREW NEW ADVENTURE celebrating the launch ASTERIX: THE SECRET OF of the Grand Cinemas THE MAGIC POTION loyalty program GOGRAND #alwaysentertaining SOCIALISE TALK MOVIES, WIN PRIZES @GCLEBANON CL BOOK NEVER MISS A MOVIE WITH E/TICKET, E/KIOSK AND THE GC MOBILE APP. EXPERIENCE FIRSTWORD FEATURING DOLBY ATMOS ISSUE 121 A new year and a new journey Hello 2019! As we head into the new year, we’re very proud to have launched the G-Points loyalty program which has been met with a tremendous response from cinema-goers—check out our launch and cross-country game tournament in GC DIARY. We look forward to LOCATIONS many more exciting announcements and movie releases to come. Our top-of-the-year issue is a banger headlined by our 2019 MUST LEBANON KUWAIT LIST, a massive round-up that gets off to a crackling start with the GRAND CINEMAS GRAND AL HAMRA ABC VERDUN LUXURY CENTER Liam Neeson revenge thriller Cold Pursuit and the action-packed 01 795 697 965 222 70 334 11 SCREENS MX4D ATMOS Dragged Across Concrete starring Mel Gibson and Vince Vaughn. MX4D featuring Study up for the year’s biggest releases, including the epic finale of DOLBY ATMOS GRAND GATE MALL Avengers: Endgame, Chris Hemsworth’s Men in Black: International, 300 CLUB SEATS 965 220 56 464 GRAND CLASS Will Smith as the genie in Aladdin, and the new entry from Quentin GRAND CINEMAS JORDAN Tarantino starring Leonardo DiCaprio and Brad Pitt. -

View Full Catalog of Encoded Compatible Content

D-BOX HOME ENTERTAINEMENT IMMERSIVE EXPERIENCES (Hold the Ctrl keyboard key and press the F (Ctrl+F) to search for a specific movie) HaptiCode Release Date RECENTLY ADDED (Year-Month-Day) Star Wars: The Bad Batch - 1st Season EP11 2021-07-09 Black Widow 2021-07-09 Lupin 1st Season EP 6,7 2021-07-07 Loki 1st Season EP 4 2021-07-06 Ace Venture - When Nature Calls 2021-07-06 Ace Ventura - Pet Detective 2021-07-06 Star Wars: The Bad Batch - 1st Season EP10 2021-07-02 Lupin 1st Season EP 4,5 2021-06-30 Loki 1st Season EP 3 2021-06-29 Star Wars: The Bad Batch - 1st Season EP9 2021-06-25 Always 2021-06-23 Lupin 1st Season EP 2,3 2021-06-23 Loki 1st Season EP 2 2021-06-22 Jack Ryan - 2nd Season EP 7,8 2021-06-22 Star Wars: The Bad Batch - 1st Season EP8 2021-06-18 Astérix - The Mansion of the Gods 2021-06-17 Lupin 1st Season EP 1 2021-06-16 Wandavision 1st Season EP 9 2021-06-16 Loki 1st Season EP 1 2021-06-15 Jack Ryan - 2nd Season EP 5,6 2021-06-15 Star Wars: The Bad Batch - 1st Season EP7 2021-06-11 In the Heights 2021-06-11 Wandavision 1st Season EP 7,8 2021-06-09 Jack Ryan - 2nd Season EP 3,4 2021-06-08 Star Wars: The Bad Batch - 1st Season EP6 2021-04-06 Conjuring : The Devil Made Me Do It 2021-06-04 Wandavision 1st Season EP 5,6 2021-06-02 Jack Ryan - 2nd Season EP 1,2 2021-06-01 Star Wars: The Bad Batch - 1st Season EP5 2021-05-28 Cruella 2021-05-28 Star Wars: The Clone Wars S07 EP 9,10,11,12 2021-05-27 Wandavision 1st Season EP 3,4 2021-05-26 Get Him to the Greek 2021-05-25 Jack Ryan 1st Season EP 7,8 2021-05-25 Star Wars: The Bad Batch -

1 Fuldstændig Premiereliste På Side 38 I DETTE

Nr. 160 - Pr. 1. januar 2019 – 46 sider – Udarbejdet af Brancheforeningen Danske Biografer Fuldstændig premiereliste på side 38 I DETTE NUMMER: Omtale af samtlige biograffilm det næste år samt HIGHLIGHTS 2020-2025 1 Omtaler af samtlige premieresatte biograffilm det næste år: 2019: BUMBLEBEE (1:53) (UIP/Paramunt) DK-premiere: 3/1-2019. (Sci-fi/action) 7 år Hjemmeside: http://www.imdb.com/title/tt4701182/ Med Hailee Steinfeld og Jorge Lendeborg, Jr. Instr.: Travis Knight (”Kubo: Den modige samurai” (14.551)). Efter at være på flugt i 1987 finder Bumblebee tilflugtssted på en losseplads i lille californisk by. 18-årige Charlie, som forsøger at finde ud af hvad hun skal bruge sit liv på, finder Bumblebee ødelagt og nedbrudt. Spin-off af Transformers-franchisen. (Indspilning i USA: $21,6 mio. – de første 3 dage.) Rotten Tomatoes: 94% - Cinemascore: A-. DESTROYER (2:03) (Scanbox) DK-premiere: 3/1-2019. (Action/drama) 15 år Hjemmeside: https://www.imdb.com/title/tt7137380/ Med Nicole Kidman, Sebastian Stan og Toby Kebbell. Instr.: Karyn Kusama. (”Girlfight” (1.099)). En kvindelig politibetjent genforenes med kollegerne fra en undercover mission, for at skabe fred. Nicole Kidman i en action-thriller, som allerede betragtes som kult. Budget : $9,0 mio. Rotten Tomatoes: 79% UNDER THE SILVER LAKE (2:19) (UIP/Mis label) DK-premiere: 3/1-2019. (Krimi/komedie) 15 år Hjemmeside: https://www.imdb.com/title/tt5691670/ Med Sydney Sweeney, Andrew Garfield og Riley Keough. Instr.: David Robert Mitchell. (”It Follows” (14.219)) En ung mand leder fortvivlet efter en kvinde, der pludselig er forsvundet. ”Ambitiøs og fascinerende.” –Owen Gleiberman, Variety. -

Screendollars About Films, the Film Industry No

For Exhibitors February 17, 2020 Screendollars About Films, the Film Industry No. 104 Newsletter and Cinema Advertising The success of IT (2017) and IT Chapter 2 (2019) created a franchise for Warner Bros., ensuring that we will be seeing more of the evil clown Pennywise in the years to come. However, these horror films based on the 1986 novel by Stephen King were not Hollywood’s first success with IT. The title was first made famous by the 1927 silent film romantic comedy starring Clara Bow. IT tells the story of a charismatic young woman who catches the eye of the handsome, wealthy owner of the department store where she is working. She becomes known as the “IT Girl", admired for her unique combination of wit, energy and beauty. Paramount released the film to theatres nationwide on 2/19/1927. IT represents the essence of the Roaring 20’s cultural aesthetic in America. (Click to Play) Weekend Box Office Results (2/14-16) Courtesy of Paul Dergarabedian (Comscore) Weekend Change Rank Title Week # Theaters Wknd $ Total $ 2/14 2/7 1/31 1 Sonic the Hedgehog (Paramount) 1 4,167 - $57.0M - - - $57.0M Birds of Prey: And the Fantabulous Emancipation 2 2 4,236 (0) $17.1M -48% - - $59.3M of One Harley Quinn (Warner Bros.) 3 Fantasy Island (Sony) 1 2,784 - $12.4M - - - $12.4M 4 The Photograph (Universal) 1 2,516 - $12.3M - - - $12.3M 5 Bad Boys for Life (Sony) 5 3,185 (-345) $11.3M -6% -32% -48% $181.3M 6 1917 (Universal) 8 2,084 (-1464) $8.1M -12% -3% -40% $144.4M 7 Jumanji: The Next Level (Sony) 10 2,729 (0) $5.7M 3% -7% -22% $305.7M 8 Parasite -

Missing Pets

13 FRIDAY, FEBRUARY 22, 2019 2- TOTAL DHAMAAL (PG-13) (HINDI/COMEDY/ADVEN- 10-ALONE / TOGETHER (PG-15) (FILIPINO/ROMANTIC/ DAILY AT: 12.15 + 3.00 + 5.45 + 8.30 + (11.15 PM THURS/FRI) OASIS JUFFAIR TURE) NEW DRAMA) NEW AJAY DEVGN, MADHURI DIXIT, ANIL KAPOOR LIZA SOBERANO, ENRIQUE GIL, JASMINE CURTIS 3- THE KNIGHT OF SHADOWS: BETWEEN YIN AND 1-FIGHTING WITH MY FAMILY (15+) (DRAMA/COME- FROM THURSDAY 21ST 7.00 PM ONWARDS DAILY AT: 11.00 AM + 1.30 + 4.00 + 6.30 + 9.00 + 11.30 PM YANG (PG-13) (ACTION/COMEDY/FANTASY) NEW DY/BIOGRAPHY) NEW DAILY AT: 10.30 AM + 1.00 + 3.45 + 6.30 + 9.15 PM + 12.00 MN JACKIE CHAN, ELANE ZHONG, ETHAN JUAN DWAYNE JOHNSON, FLORENCE PUGH, JACK LOWDEN 11-ALITA: BATTLE ANGEL (PG-15) (ACTION/ADVEN- DAILY AT: 10.45 AM + 1.00 + 6.15 + (11.30 PM THURS/FRI) DAILY AT: 12.30 + 5.00 + 9.30 PM 3- DUMPLIN (15+) (COMEDY/DRAMA) NEW TURE/ROMANTIC) DAILY AT (VIP): 10.45 AM + 3.30 + 8.15 PM DANIELLE MACDONALD, JENNIFER ANISTON, ROSA SALAZAR, CHRISTOPH WALTZ, JENNIFER CONNELLY 4-ALITA: BATTLE ANGEL (PG-15) (ACTION/ADVEN- LUKE BENWARD DAILY AT: 11.30 AM + 2.00 + 4.30 + 7.00 + 9.30 PM + 12.00 MN TURE/ROMANTIC) 2-TOTAL DHAMAAL (PG-13) (HINDI/COMEDY/ADVEN- DAILY AT: 12.00 + 2.15 + 4.30 + 6.45 + 9.00 + 11.15 PM ROSA SALAZAR, CHRISTOPH WALTZ, JENNIFER CONNELLY TURE) NEW 12-GULLY BOY (PG-15) (HINDI/DRAMA/MUSICAL) DAILY AT: 6.00 + 8.30 + (11.00 PM THURS/FRI) AJAY DEVGN, MADHURI DIXIT, ANIL KAPOOR 4- UPGRADE (15+) (ACTION/THRILLER) NEW ALIA BHAT, RANVEER SINGH, SIDDHANT CHATURVEDI FROM THURSDAY 21ST 7.00 PM ONWARDS LOGAN MARSHALL-GREEN, RICHARD -

UK RELEASE DATE UK Publicity Contacts

UK RELEASE DATE February 22nd 2019 UK Publicity Contacts [email protected] [email protected] Images and Press materials: www.studiocanalpress.co.uk 1 SYNOPSIS Welcome to Kehoe, it’s -10 degrees and counting at this glitzy ski resort in the Rocky Mountains. The local police aren’t used to much action until the son of unassuming town snowplough driver, Nels Coxman (Liam Neeson), is murdered at the order of Viking (Tom Bateman), a flamboyant drug lord. Fueled by rage and armed with heavy machinery, Nels sets out to dismantle the cartel one man at a time, but his understanding of murder comes mainly from what he read in a crime novel. As the bodies pile up, his actions ignite a turf war between Viking and his long-standing rival White Bull (Tom Jackson), a soulful Native- American mafia boss, that will quickly escalate and turn the small town’s bright white slopes blood-red. 2 BLOOD IN THE SNOW Director Hans Petter Moland and Liam Neeson team up for a dramatic thriller that mixes icy revenge and dark humor “It’s a whirlwind of vengeance, violence and dark humour.” - Liam Neeson “A whole can of worms.” That’s how Liam Neeson describes what his character opens in Hans Petter Moland’s blisteringly violent and bitingly hilarious COLD PURSUIT. “My character goes out on a path of vengeance, but doesn’t realise what he’s getting himself into,” says Neeson. “He thinks he’s going after one guy who killed his son. In actual fact, it all escalates into a whirlwind of vengeance and violence.