Name Description

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Assignment 4 Computer Science 235 Due Start of Class, October 4, 2005

Assignment 4 Computer Science 235 Due Start of Class, October 4, 2005 This assignment is intended as an introduction to OCAML programming. As always start early and stop by if you have any questions. Exercise 4.1. Twenty higher-order OCaml functions are listed below. For each function, write down the type that would be automatically reconstructed for it. For example, consider the following OCaml length function: let length xs = match xs with [] -> 0 | (_::xs') = 1 + (length xs') The type of this OCaml function is: 'a list -> int Note: You can check your answers by typing them into the OCaml interpreter. But please write down the answers first before you check them --- otherwise you will not learn anything! let id x = x let compose f g x = (f (g x)) let rec repeated n f = if (n = 0) then id else compose f (repeated (n - 1) f) let uncurry f (a,b) = (f a b) let curry f a b = f(a,b) let churchPair x y f = f x y let rec generate seed next isDone = if (isDone seed) then [] else seed :: (generate (next seed) next isDone) let rec map f xs = match xs with [] -> [] Assignment 4 Page 2 Computer Science 235 | (x::xs') -> (f x) :: (map f xs') let rec filter pred xs = match xs with [] -> [] | (x::xs') -> if (pred x) then x::(filter pred xs') else filter pred xs' let product fs xs = map (fun f -> map (fun x -> (f x)) xs) fs let rec zip pair = match pair with ([], _) -> [] | (_, []) -> [] | (x::xs', y::ys') -> (x,y)::(zip(xs',ys')) let rec unzip xys = match xys with [] -> ([], []) | ((x,y)::xys') -> let (xs,ys) = unzip xys' in (x::xs, y::ys) let rec -

Teach Yourself Perl 5 in 21 Days

Teach Yourself Perl 5 in 21 days David Till Table of Contents: Introduction ● Who Should Read This Book? ● Special Features of This Book ● Programming Examples ● End-of-Day Q& A and Workshop ● Conventions Used in This Book ● What You'll Learn in 21 Days Week 1 Week at a Glance ● Where You're Going Day 1 Getting Started ● What Is Perl? ● How Do I Find Perl? ❍ Where Do I Get Perl? ❍ Other Places to Get Perl ● A Sample Perl Program ● Running a Perl Program ❍ If Something Goes Wrong ● The First Line of Your Perl Program: How Comments Work ❍ Comments ● Line 2: Statements, Tokens, and <STDIN> ❍ Statements and Tokens ❍ Tokens and White Space ❍ What the Tokens Do: Reading from Standard Input ● Line 3: Writing to Standard Output ❍ Function Invocations and Arguments ● Error Messages ● Interpretive Languages Versus Compiled Languages ● Summary ● Q&A ● Workshop ❍ Quiz ❍ Exercises Day 2 Basic Operators and Control Flow ● Storing in Scalar Variables Assignment ❍ The Definition of a Scalar Variable ❍ Scalar Variable Syntax ❍ Assigning a Value to a Scalar Variable ● Performing Arithmetic ❍ Example of Miles-to-Kilometers Conversion ❍ The chop Library Function ● Expressions ❍ Assignments and Expressions ● Other Perl Operators ● Introduction to Conditional Statements ● The if Statement ❍ The Conditional Expression ❍ The Statement Block ❍ Testing for Equality Using == ❍ Other Comparison Operators ● Two-Way Branching Using if and else ● Multi-Way Branching Using elsif ● Writing Loops Using the while Statement ● Nesting Conditional Statements ● Looping Using -

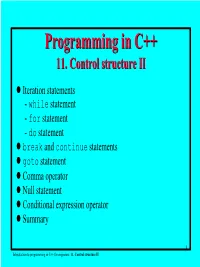

Programming Inin C++C++ 11.11

ProgrammingProgramming inin C++C++ 11.11. ControlControl structurestructure IIII ! Iteration statements - while statement - for statement - do statement ! break and continue statements ! goto statement ! Comma operator ! Null statement ! Conditional expression operator ! Summary 1 Introduction to programming in C++ for engineers: 11. Control structure II IterationIteration statements:statements: whilewhile statementstatement The while statement takes the general form: while (control) statement The control expression which is of arithmetic type is evaluated before each execution of what is in a statement. This statement is executed if the expression is not zero and then the test is repeated. There is no do associated with the while!!! int n =5; double gamma = 1.0; while (n > 0) { gamma *= n-- } If the test never fails then the iteration never terminates. 2 Introduction to programming in C++ for engineers: 11. Control structure II IterationIteration statements:statements: forfor statementstatement The for statement has the general form: for (initialize; control; change) statement The initialize expression is evaluated first. If control is non-zero statement is executed. The change expression is then evaluated and if control is still non-zero statement is executed again. Control continues to cycle between control, statement and change until the control expression is zero. long unsigned int factorial = 1; for(inti=1;i<=n; ++i) { factorial *= i; } Initialize is evaluated only once! 3 Introduction to programming in C++ for engineers: 11. Control structure II IterationIteration statements:statements: forfor statementstatement It is also possible for any (or even all) of the expressions (but not the semicolons) to be missing: int factorial = 1,i=1; for (; i<= n; ) { factorial *= i++; { If the loop variable is defined in the initialize expression the scope of it is the same as if the definition occurred before the for loop. -

Component-Based Semantics in K

FunKons: Component-Based Semantics in K Peter D. Mosses and Ferdinand Vesely Swansea University, Swansea, SA2 8PP, United Kingdom [email protected], [email protected] Abstract. Modularity has been recognised as a problematic issue of programming language semantics, and various semantic frameworks have been designed with it in mind. Reusability is another desirable feature which, although not the same as modularity, can be enabled by it. The K Framework, based on Rewriting Logic, has good modularity support, but reuse of specications is not as well developed. The PLanCompS project is developing a framework providing an open- ended collection of reusable components for semantic specication. Each component species a single fundamental programming construct, or `funcon'. The semantics of concrete programming language constructs is given by translating them to combinations of funcons. In this paper, we show how this component-based approach can be seamlessly integrated with the K Framework. We give a component-based denition of CinK (a small subset of C++), using K to dene its translation to funcons as well as the (dynamic) semantics of the funcons themselves. 1 Introduction Even very dierent programming languages often share similar constructs. Con- sider OCaml's conditional `if E1 then E2 else E3' and the conditional oper- ator `E1 ? E2 : E3' in C. These constructs have dierent concrete syntax but similar semantics, with some variation in details. We would like to exploit this similarity when dening formal semantics for both languages by reusing parts of the OCaml specication in the C specication. With traditional approaches to semantics, reuse through copy-paste-and-edit is usually the only option that is available to us. -

Name Description

Perl version 5.10.0 documentation - perltrap NAME perltrap - Perl traps for the unwary DESCRIPTION The biggest trap of all is forgetting to use warnings or use the -wswitch; see perllexwarn and perlrun. The second biggest trap is notmaking your entire program runnable under use strict. The third biggesttrap is not reading the list of changes in this version of Perl; see perldelta. Awk Traps Accustomed awk users should take special note of the following: A Perl program executes only once, not once for each input line. You cando an implicit loop with -n or -p. The English module, loaded via use English; allows you to refer to special variables (like $/) with names (like$RS), as though they were in awk; see perlvar for details. Semicolons are required after all simple statements in Perl (exceptat the end of a block). Newline is not a statement delimiter. Curly brackets are required on ifs and whiles. Variables begin with "$", "@" or "%" in Perl. Arrays index from 0. Likewise string positions in substr() andindex(). You have to decide whether your array has numeric or string indices. Hash values do not spring into existence upon mere reference. You have to decide whether you want to use string or numericcomparisons. Reading an input line does not split it for you. You get to split itto an array yourself. And the split() operator has differentarguments than awk's. The current input line is normally in $_, not $0. It generally doesnot have the newline stripped. ($0 is the name of the programexecuted.) See perlvar. $<digit> does not refer to fields--it refers to substrings matchedby the last match pattern. -

YAGL: Yet Another Graphing Language Language Reference Manual

YAGL: Yet Another Graphing Language Language Reference Manual Edgar Aroutiounian, Jeff Barg, Robert Cohen July 23, 2014 Abstract YAGL is a programming language for generating graphs in SVG format from JSON for- matted data. 1 Introduction This manual describes the YAGL programming language as specified by the YAGL team. 2 Lexical Conventions A YAGL program is written in the 7-bit ASCII character set and is divided into a number of logical lines. A logical line terminates by the token NEWLINE, where a logical line is constructed from one or more physical lines. A physical line is a sequence of ASCII characters that are terminated by an end-of-line character. All blank lines are ignored entirely. 2.1 Tokens Besides the NEWLINE token, the following tokens also exist: NAME, INTEGER, STRING, and OPERATOR, where a LITERAL is either a String literal or an Integer literal. 1 2.2 Comments Comments are introduced by the '#' character and last until they encounter a NEWLINE token, comments do not nest. 2.3 Identifiers An identifier is a sequence of ASCII letters including underscores where upper and lower case count as different letters; ASCII digits may not be included in an identifier. 2.4 Keywords The following is an enumeration of all the keywords required by a YAGL implementation: 'if', `elif', 'for', 'in', 'break', 'func', 'else', 'return', 'continue', 'print', 'while' 2.5 String Literals YAGL string literals begin with a double-quote (") followed by a finite sequence of ASCII characters and close with a double-quote ("). YAGL strings do not recognize escape sequences. -

Case Sensitivity Dot Syntax Literals Semicolons Parentheses

Case sensitivity ActionScript 3.0 is a case-sensitive language. Identifiers that differ only in case are considered different identifiers. For example, the following code creates two different variables: Dot syntax The dot operator ( . ) provides a way to access the properties and methods of an object. Using dot syntax, you can refer to a class property or method by using an instance name, followed by the dot operator and name of the property or method. For example, consider the following class definition: Literals A literal is a value that appears directly in your code. The following examples are all literals: 17 "hello" -3 9.4 null undefined true false Semicolons You can use the semicolon character ( ; ) to terminate a statement. Alternatively, if you omit the semicolon character, the compiler will assume that each line of code represents a single statement. Because many programmers are accustomed to using the semicolon to denote the end of a statement, your code may be easier to read if you consistently use semicolons to terminate your statements. Parentheses You can use parentheses ( () ) in three ways in ActionScript 3.0. First, you can use parentheses to change the order of operations in an expression. Operations that are grouped inside parentheses are always executed first. For example, parentheses are used to alter the order of operations in the following code: trace(2 + 3 * 4); // 14 trace((2 + 3) * 4); // 20 Second, you can use parentheses with the comma operator ( , ) to evaluate a series of expressions and return the result of the final expression, as shown in the following example: var a:int = 2; var b:int = 3; trace((a++, b++, a+b)); // 7 Third, you can use parentheses to pass one or more parameters to functions or methods, as shown in the following example, which passes a String value to the trace() function: trace("hello"); // hello Comments ActionScript 3.0 code supports two types of comments: single-line comments and multiline comments. -

Ecmascript: a General Purpose, Cross-Platform Programming Language

Standard ECMA-262 June 1997 Standardizing Information and Communication Systems ECMAScript: A general purpose, cross-platform programming language Phone: +41 22 849.60.00 - Fax: +41 22 849.60.01 - URL: http://www.ecma.ch - Internet: [email protected] . Standard ECMA-262 June 1997 Standardizing Information and Communication Systems ECMAScript : A general purpose, cross-platform programming language Phone: +41 22 849.60.00 - Fax: +41 22 849.60.01 - URL: http://www.ecma.ch - Internet: [email protected] IW Ecma-262.doc 16-09-97 12,08 . Brief History This ECMA Standard is based on several originating technologies, the most well known being JavaScript™ (Netscape Communications) and JScript™ (Microsoft Corporation). The development of this Standard has started in November 1996. The ECMA Standard is submitted to ISO/IEC JTC 1 for adoption under the fast-track procedure. This ECMA Standard has been adopted by the ECMA General Assembly of June 1997. - i - Table of contents 1 Scope 1 2 Conformance 1 3 References 1 4 Overview 1 4.1 Web Scripting 2 4.2 Language Overview 2 4.2.1 Objects 2 4.3 Definitions 3 4.3.1 Type 3 4.3.2 Primitive value 3 4.3.3 Object 3 4.3.4 Constructor 4 4.3.5 Prototype 4 4.3.6 Native object 4 4.3.7 Built-in object 4 4.3.8 Host object 4 4.3.9 Undefined 4 4.3.10 Undefined type 4 4.3.11 Null 4 4.3.12 Null type 4 4.3.13 Boolean value 4 4.3.14 Boolean type 4 4.3.15 Boolean object 4 4.3.16 String value 4 4.3.17 String type 5 4.3.18 String object 5 4.3.19 Number value 5 4.3.20 Number type 5 4.3.21 Number object 5 4.3.22 Infinity 5 4.3.23 -

Javascript Technical Interview Questions Prepare Yourself for That Dream Job

Javascript Technical Interview Questions Prepare Yourself For That Dream Job Xuanyi Chew This book is for sale at http://leanpub.com/jsinterviewquestions This version was published on 2014-03-19 This is a Leanpub book. Leanpub empowers authors and publishers with the Lean Publishing process. Lean Publishing is the act of publishing an in-progress ebook using lightweight tools and many iterations to get reader feedback, pivot until you have the right book and build traction once you do. ©2014 Xuanyi Chew Contents Sample of Underhanded JavaScript ............................. 1 Introduction .......................................... 2 On IIFE Behaviour ...................................... 3 The Explanation ....................................... 4 Exceptions .......................................... 5 During The Interview .................................... 6 On The Comma Operator ................................... 7 The Explanation ....................................... 7 Miscelleny .......................................... 9 Practice Questions ...................................... 10 During The Interview .................................... 11 On Object Coercion ...................................... 12 The Explanation ....................................... 13 Practice Questions ...................................... 15 During The Interview .................................... 16 Sample of Underhanded JavaScript Hi there! This is the sample of Underhanded JavaScript: How to Be A Complete Arsehole With Bad JavaScript. Included -

Minimalistic BASIC Compiler (MBC) Document Version 1.0 Language Reference Manual (LRM) Joel Christner (Jec2160) Via CVN

COMS‐W4115 Spring 2009 Programming Languages and Translators Professor Stephen Edwards MinimalistiC BASIC Compiler (MBC) Document Version 1.0 Language ReferenCe Manual (LRM) Joel Christner (jec2160) via CVN March 10th, 2009 Table of Contents Table of Contents..................................................................................................................... 2 1. Introduction.......................................................................................................................... 3 1.1 IntroduCtion to MBC..........................................................................................................................................3 1.2 Styles Used in this DoCument........................................................................................................................3 1.3 No Humor Found Here.....................................................................................................................................3 2. Lexical Conventions and Program Structure............................................................. 3 2.1 General Program Requirements ..................................................................................................................3 2.1.1 Numerical Line Identifiers ..........................................................................................................................3 2.1.2 Program Termination...................................................................................................................................4 -

Concept and Implementation of C+++, an Extension of C++ to Support User-Defined Operator Symbols and Control Structures

Concept and Implementation of C+++, an Extension of C++ to Support User-Defined Operator Symbols and Control Structures Christian Heinlein Dept. of Computer Structures, University of Ulm, Germany [email protected] Abstract. The first part of this report presents the concepts of C+++, an extension of C++ allowing the programmer to define newoperator symbols with user-defined priori- ties by specifying a partial precedence relationship. Furthermore, so-called fixary opera- tor combinations consisting of a sequence of associated operator symbols to connect a fixednumber of operands as well as flexary operators connecting anynumber of operands are supported. Finally,operators with lazily evaluated operands are supported which are particularly useful to implement newkinds of control structures,especially as theyaccept whole blocks of statements as operands, too. In the second part of the report, the implementation of C+++ by means of a “lazy” precompiler for C++ is described in detail. 1Introduction Programming languages such as Ada [12] and C++ [10, 4] support the concept of operator overload- ing,i.e., the possibility to redefine the meaning of built-in operators for user-defined types. Since the built-in operators of manylanguages are already overloaded to a certain degree in the language itself (e. g., arithmetic operators which can be applied to integer and floating point numbers, or the plus op- erator which is often used for string concatenation as well), it appears rather natural and straightfor- ward to extend this possibility to user-defined types (so that, e. g., plus can be defined to add complex numbers, vectors, matrices, etc., too). -

Server-Side Javascript 1.2 Reference

World Wide Web security URLmerchant systemChat community system server navigator TCP/IP HTML Publishing PersonalServer-Side JavaScript Reference Inter ww Version 1.2 Proxy SSL Mozilla IStore Publishing Internet secure sockets layer mail encryption HTMLhttp://www comp.syselectronic commerce JavaScript directory server news certificate Proxy Netscape Communications Corporation ("Netscape") and its licensors retain all ownership rights to the software programs offered by Netscape (referred to herein as "Software") and related documentation. Use of the Software and related documentation is governed by the license agreement accompanying the Software and applicable copyright law. Your right to copy this documentation is limited by copyright law. Making unauthorized copies, adaptations, or compilation works is prohibited and constitutes a punishable violation of the law. Netscape may revise this documentation from time to time without notice. THIS DOCUMENTATION IS PROVIDED "AS IS" WITHOUT WARRANTY OF ANY KIND. IN NO EVENT SHALL NETSCAPE BE LIABLE FOR INDIRECT, SPECIAL, INCIDENTAL, OR CONSEQUENTIAL DAMAGES OF ANY KIND ARISING FROM ANY ERROR IN THIS DOCUMENTATION, INCLUDING WITHOUT LIMITATION ANY LOSS OR INTERRUPTION OF BUSINESS, PROFITS, USE, OR DATA. The Software and documentation are copyright ©1994-1998 Netscape Communications Corporation. All rights reserved. Netscape, Netscape Navigator, Netscape Certificate Server, Netscape DevEdge, Netscape FastTrack Server, Netscape ONE, SuiteSpot and the Netscape N and Ship’s Wheel logos are registered trademarks of Netscape Communications Corporation in the United States and other countries. Other Netscape logos, product names, and service names are also trademarks of Netscape Communications Corporation, which may be registered in other countries. JavaScript is a trademark of Sun Microsystems, Inc. used under license for technology invented and implemented by Netscape Communications Corporation.