Religious Satire and Narrative Ambiguity in the Known World

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

PHILIP ROTH and the STRUGGLE of MODERN FICTION by JACK

PHILIP ROTH AND THE STRUGGLE OF MODERN FICTION by JACK FRANCIS KNOWLES A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY in THE FACULTY OF GRADUATE AND POSTDOCTORAL STUDIES (English) THE UNIVERSITY OF BRITISH COLUMBIA (Vancouver) July 2020 © Jack Francis Knowles, 2020 The following individuals certify that they have read, and recommend to the Faculty of Graduate and Postdoctoral Studies for acceptance, the dissertation entitled: Philip Roth and The Struggle of Modern Fiction in partial fulfillment of the requirements submitted by Jack Francis Knowles for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in English Examining Committee: Ira Nadel, Professor, English, UBC Supervisor Jeffrey Severs, Associate Professor, English, UBC Supervisory Committee Member Michael Zeitlin, Associate Professor, English, UBC Supervisory Committee Member Lisa Coulthard, Associate Professor, Film Studies, UBC University Examiner Adam Frank, Professor, English, UBC University Examiner ii ABSTRACT “Philip Roth and The Struggle of Modern Fiction” examines the work of Philip Roth in the context of postwar modernism, tracing evolutions in Roth’s shifting approach to literary form across the broad arc of his career. Scholarship on Roth has expanded in both range and complexity over recent years, propelled in large part by the critical esteem surrounding his major fiction of the 1990s. But comprehensive studies of Roth’s development rarely stray beyond certain prominent subjects, homing in on the author’s complicated meditations on Jewish identity, a perceived predilection for postmodern experimentation, and, more recently, his meditations on the powerful claims of the American nation. This study argues that a preoccupation with the efficacies of fiction—probing its epistemological purchase, questioning its autonomy, and examining the shaping force of its contexts of production and circulation— roots each of Roth’s major phases and drives various innovations in his approach. -

Buffalo & Erie County Public Library

The great American abolitionist, writer and Those enslaved TELLING THE STORY: orator Frederick suffered greatly during Douglass once the Middle Passage, or said, “Slavery is the transatlantic crossing, Enslavement great test question and upon arrival, endured unimaginable of African People of our age and Solomon Northup Twelve Years a Slave physical, cultural, and in the United States nation.” Now, 400 intellectual brutality years after the first by their enslavers. This inhumanity is well African people were Buffalo & Erie County documented in shipping records, bills of sale, Public Library captured, enslaved Slave Auction advertisements and personal and transported to Slave Ship Diagram accounts of the the United States, the enslaved. repercussions of this horrific practice remain with us today. This Library exhibit highlights its Supporters of History of Slavery Collection slavery were and, perhaps more typically enslavers ambitiously, to provoke themselves. community conversations Early arguments for slavery were about our country’s Notice of Slave Auction history of enslavement simplistic and merely and its continuing to defend against On display through July 2020 attacks made against the aftermath. practice. Later arguments Downtown Central Library or rationalizations were From antiquity to 1 Lafayette Square protective, religious and modern day, enslavement has existed racist. Slavery was an Grosvenor Room in one form or another. Institutionalized institution of power and Rare Book Display Room slavery—mostly for the powerful people who Ring of Knowledge agricultural labor— protected it to protect Main floor thrived in the American their own profits. English colonies and was central to the Protections for slavery Buffalo & Erie County Public development and were embedded in Cotton is King and Olaudah Equiano - economic growth of America’s founding , The Life of Olaudah Equiano Pro-Slavery Arguments LIBRARYwww.BuffaloLib.org the United States. -

11 Th Grade American Literature Summer Assignment (20192020 School Y Ear)

6/26/2019 American Lit Summer Reading 2019-20 - Google Docs 11 th Grade American Literature Summer Assignment (20192020 School Y ear) Welcome to American Literature! This summer assignment is meant to keep your reading and writing skills fresh. You should choose carefully —select books that will be interesting and enjoyable for you. Any assignments that do not follow directions exactly will not be accepted. This assignment is due Friday, August 16, 2019 to your American Literature Teacher. This will count as your first formative grade and be used as a diagnostic for your writing ability. Directions: For your summer assignment, please choose o ne of the following books to read. You can choose if your book is Fiction or Nonfiction. Fiction Choices Nonfiction Choices Catch 22 by Joseph Heller The satirical story of a WWII soldier who The Short and Tragic Life of Robert Peace by Jeff Hobbs. An account thinks everyone is trying to kill him and hatches plot after plot to keep of a young African‑American man who escaped Newark, NJ, to attend from having to fly planes again. Yale, but still faced the dangers of the streets when he returned is, Bastard Out of Carolina by Dorothy Allison The story of an abusive “nuanced and shattering” ( People ) and “mesmeric” ( The New York Southern childhood. Times Book Review ) . The Known World by Edward P. Jones The story of a black, slave Outliers / Blink / The Tipping Point by Malcolm Gladwell Fascinating owning family. statistical studies of everyday phenomena. For Whom the Bell Tolls by Ernest Hemingway A young American The Hot Zone: A Terrifying True Story by Richard Preston There is an anti‑fascist guerilla in the Spanish civil war falls in love with a complex outbreak of ebola virus in an American lab, and other stories of germs woman. -

History of Slavery in America - Student Success Day

9/22/20 History of Slavery in America - Student Success Day 1619 or 1776? Presented by Chris Stout Sep 22, 2020 11:00 AM 1 A Global Enterprise • All Western European nations participated in the African slave trade. • The slave trade was dominated by the Portuguese in the sixteenth century, the Dutch in the sugar boom of the seventeenth century, and the English who entered the trade in the seventeenth century. • Over 10 – 12 million slaves between 1700 – 1800 • Majority were between the age of 15 and 30 • New England slavers entered the trade in the eighteenth century. • Newport RI, more than 100K slaves carried in the 18th century • Collaboration between American, European, and Africans enabled the trade http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=B0geOQ25Pyw 2 2 1 9/22/20 MAP 4.2 Slave Colonies of the Seventeenth and Eighteenth Centuries By the eighteenth century, the system of slavery had created societies with large African populations throughout the Caribbean and along the southern coast of North America. 3 3 The Tobacco Colonies https://www.youtube.c om/watch?v=DSDek9M • Tobacco was the most important -hSk commodity produced in eighteenth century North America, accounting for 25% of the value of all colonial exports. • Slavery allowed the expansion of tobacco production since it was labor- intensive. • Using slave labor, tobacco was grown on large plantations and small farms. • The slave population in this region grew largely by natural increase. 4 4 2 9/22/20 FIGURE 4.3 Value of Colonial Exports by Region, Annual Average, 1768–72 With tobacco, rice, grain, and indigo, the Chesapeake and Lower South accounted for nearly two-thirds of colonial exports in the late eighteenth century. -

English Department Suggested Summer Reading Choices

English Department Suggested Summer Reading Choices For more information on any of the following titles, and additional book selections visit one of the following websites for book reviews: http://www.nytimes.com/pages/books/ http://www.reviewsofbooks.com/ http://www.barnesandnoble.com/bookstore.asp?r=1&popup=0 FICTION Allison, Dorothy Bastard Out of Carolina Allende, Isabel The House of Spirits Alvarez, Julia How the Garcia Girls Lost their Accents, In The Time of the Butterflies Anderson, Sherwood Winesburg, Ohio (Stories) Atwood, Margaret Cat’s Eye, The Handmaid’s Tale, Alias Grace Austen, Jane Emma, Mansfield Park, Persuasion, Northanger Abbey, Sense and Sensibility, Pride and Prejudice Baldwin, James If Beale Street Could Talk Bellow, Saul Seize the Day, Henderson the Rain King Best American Short Stories from any year Borges, Jorge Luis Labyrinths Bronte, Charlotte Villette, Northanger Abbey, Bronte, Emily Wuthering Heights Buck, Pearl S. The Good Earth Camus, Albert The Stranger Capote, Truman, In Cold Blood, Breakfast at Tiffany’s Cather, Willa My Antonia, O Pioneers Cervantes, Miguel de Don Quixote Chabon, Michael, The Amazing Adventures of Kavalier and Klay, The Yiddish Policeman’s Union, Wonder Boys Chevalier, Tracy Girl With A Pearl Earring Chopin, Kate The Awakening Cisneros, Sandra Woman Hollering Creek Crane, Stephen The Red Badge of Courage Cunningham, Michael At Home at the End of the World Defoe, Daniel Robinson Crusoe Dickens, Charles David Copperfield, A Tale of Two Cities Dostoevsky, Fyodor Crime and Punishment Dumas, Alexander The Count of Monte Cristo du Maurier, Daphne Rebecca Eggers, Dave What is the What Eliot, George The Mill on the Floss, Silas Marner Ellison, Ralph Invisible Man Erdrich, Louise Love Medicine, The Beet Queen, Tracks, The Painted Drum, et. -

Introduction: Ethics of the Narrative

doi: https://doi.org/10.26262/exna.v1i1.5990 Introduction: Ethics of the Narrative Helena Maragou a, Theodora Tsimpouki b aDeree—The American College of Greece. b The National and Kapodistrian University of Athens, Greece. If a man could write a book on Ethics which really was a book on Ethics, this book would, with an explosion, destroy all the other books in the world. 1 The debate on whether literature does or should possess ethical relevance is both old and new. As far back as in the ancient times, Plato and Aristotle addressed the ways in which aesthetic structure produces affective power, as well as the extent to which the affective power of literature may provide direction, or in fact—as in the case of Plato’s famous critique of poetry—misdirection to an audience’s moral consciousness. In more recent years, in the mid-1980s and early 1990s, the intersections of literature and ethics became the focus of work by Wayne C. Booth,2 who theorized on the moral functioning of rhetorical practices, and Martha C. Nussbaum,3 who addressed literature from the perspective of moral philosophy. In an article published in the 2004 special issue of Poetics Today, which focused on Ethics and Literature, Michael Eskin4 draws attention to moral philosophy’s “turn to literature,” a move that aims to embed moral philosophy’s abstract investigations into the concrete domain of human and social relations opened up by literature. At the same time, however, philosophy’s turn toward literature has coincided with a turn of literary studies toward ethics,5 a fact which some attribute to a reaction against formalism and poststructuralism. -

On-The-Go Book Club Bags

Resources for Book Clubs: On-the-Go Book Club Bags MARPLE LIBRARY 2599 Sproul Road Broomall, PA 19008 Our On-the-Go Book Club Bags can be checked out (610) 356-1510 for up to 8 weeks. www.marplelibrary.org Late fees are $3 per day. Each bag contains: Multiple copies of the book Large-print edition (when available) Audiobook (when available) A folder with discussion questions See a Librarian at the Reference Desk for more information or to reserve a bag. Updated April 2021 Bag 1: The Known World by Edward P. Jones When a plantation proprietor and former slave--now possessing slaves of his own--dies, his household falls apart in the wake of a slave rebellion and corrupt underpaid patrollers who enable free black people to be sold into slavery. Bag 2: In the Midst of Winter by Isabel Allende A minor traffic accident becomes the catalyst for an unexpected and moving love story between two peo- ple who thought they were deep into the winter of heir lives. Bag 3: March by Geraldine Brooks In a story inspired by the father character in "Little Women" and drawn from the journals and letters of The Marple Public Library Louisa May Alcott's father, a man leaves behind his family to serve in the Civil War and finds his beliefs challenged by his experiences. expresses its gratitude to the Bag 4: A Piece of the World by Christina Baker Kline Friends of the Library Imagines the life story of Christina Olson, the subject of Andrew Wyeth's painting "Christina's World," de- scribing the simple life she led on a remote Maine for the funds donated to farm, her complicated relationship with her family, and the illness that incapacitated her. -

Chapter 15: Resources This Is by No Means an Exhaustive List. It's Just

Chapter 15: Resources This is by no means an exhaustive list. It's just meant to get you started. ORGANIZATIONS African Americans for Humanism Supports skeptics, doubters, humanists, and atheists in the African American community, provides forums for communication and education, and facilitates coordinated action to achieve shared objectives. <a href="http://aahumanism.net">aahumanism.net</a> American Atheists The premier organization laboring for the civil liberties of atheists and the total, absolute separation of government and religion. <a href="http://atheists.org">atheists.org</a> American Humanist Association Advocating progressive values and equality for humanists, atheists, and freethinkers. <a href="http://americanhumanist.org">americanhumanist.org</a> Americans United for Separation of Church and State A nonpartisan organization dedicated to preserving church-state separation to ensure religious freedom for all Americans. <a href="http://au.org">au.org</a> Atheist Alliance International A global federation of atheist and freethought groups and individuals, committed to educating its members and the public about atheism, secularism and related issues. <a href="http://atheistalliance.org">atheistalliance.org</a> Atheist Alliance of America The umbrella organization of atheist groups and individuals around the world committed to promoting and defending reason and the atheist worldview. <a href="http://atheistallianceamerica.org">atheistallianceamerica.org< /a> Atheist Ireland Building a rational, ethical and secular society free from superstition and supernaturalism. <a href="http://atheist.ie">atheist.ie</a> Black Atheists of America Dedicated to bridging the gap between atheism and the black community. <a href="http://blackatheistsofamerica.org">blackatheistsofamerica.org </a> The Brights' Net A bright is a person who has a naturalistic worldview. -

Triangular Trade and the Middle Passage

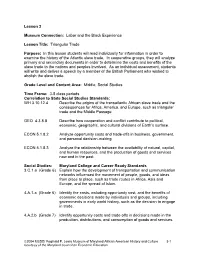

Lesson 3 Museum Connection: Labor and the Black Experience Lesson Title: Triangular Trade Purpose: In this lesson students will read individually for information in order to examine the history of the Atlantic slave trade. In cooperative groups, they will analyze primary and secondary documents in order to determine the costs and benefits of the slave trade to the nations and peoples involved. As an individual assessment, students will write and deliver a speech by a member of the British Parliament who wished to abolish the slave trade. Grade Level and Content Area: Middle, Social Studies Time Frame: 3-5 class periods Correlation to State Social Studies Standards: WH 3.10.12.4 Describe the origins of the transatlantic African slave trade and the consequences for Africa, America, and Europe, such as triangular trade and the Middle Passage. GEO 4.3.8.8 Describe how cooperation and conflict contribute to political, economic, geographic, and cultural divisions of Earth’s surface. ECON 5.1.8.2 Analyze opportunity costs and trade-offs in business, government, and personal decision-making. ECON 5.1.8.3 Analyze the relationship between the availability of natural, capital, and human resources, and the production of goods and services now and in the past. Social Studies: Maryland College and Career Ready Standards 3.C.1.a (Grade 6) Explain how the development of transportation and communication networks influenced the movement of people, goods, and ideas from place to place, such as trade routes in Africa, Asia and Europe, and the spread of Islam. 4.A.1.a (Grade 6) Identify the costs, including opportunity cost, and the benefits of economic decisions made by individuals and groups, including governments in early world history, such as the decision to engage in trade. -

Narrative, Identity and Academic Storytelling Narrations, Identités Et Récits Académiques

ILCEA Revue de l’Institut des langues et cultures d'Europe, Amérique, Afrique, Asie et Australie 31 | 2018 Récits fictionnels et non fictionnels liés à des communautés professionnelles et à des groupes spécialisés Narrative, Identity and Academic Storytelling Narrations, identités et récits académiques Ken Hyland Electronic version URL: http://journals.openedition.org/ilcea/4677 DOI: 10.4000/ilcea.4677 ISSN: 2101-0609 Publisher UGA Éditions/Université Grenoble Alpes Printed version ISBN: 978-2-37747-043-3 ISSN: 1639-6073 Electronic reference Ken Hyland, « Narrative, Identity and Academic Storytelling », ILCEA [Online], 31 | 2018, Online since 06 March 2018, connection on 30 April 2019. URL : http://journals.openedition.org/ilcea/4677 ; DOI : 10.4000/ilcea.4677 This text was automatically generated on 30 April 2019. © ILCEA Narrative, Identity and Academic Storytelling 1 Narrative, Identity and Academic Storytelling Narrations, identités et récits académiques Ken Hyland Introduction 1 Most simply, a narrative is a spoken or written account of connected events: a story. Narratives in the social sciences, particularly those elicited through biographical interviews, have become the preferred method of data collection for researchers interested in identity and the connections between structure and agency (e.g. Block, 2006). The idea is that identity can be explored through the stories we tell about ourselves, tapping into the accounts that individuals select, structure and relate at appropriate moments. The underlying emphasis is on reflexivity and the belief that storytelling is an active process of summation, where we re-present a particular aspect of our lives. Giddens (1991) argues that self and reflexivity are interwoven so that identity is not the possession of particular character traits, but the ability to construct a reflexive narrative of the self. -

Narratology and Other Theories of Fictional Narrative Sylvie Patron

On the Epistemology of Narrative Theory : Narratology and Other Theories of Fictional Narrative Sylvie Patron To cite this version: Sylvie Patron. On the Epistemology of Narrative Theory : Narratology and Other Theories of Fictional Narrative. Matti Hyvärinen, Anu Korhonen et Juri Mykkänen. The Traveling Con- cept of Narrative, COLLeGIUM. Studies across Disciplines in the Humanities and Social Sciences, http://www.helsinki.fi/collegium/e-series/volumes/volume_1/index.htm ; pp. 118-133, 2006. hal- 00698697v2 HAL Id: hal-00698697 https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-00698697v2 Submitted on 28 Mar 2013 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. On the Epistemology of Narrative Theory: Narratology and Other Theories of Fictional Narrative Sylvie Patron University of Paris 7-Denis Diderot (Translated by Anne Marsella) Introduction The work of Gérard Genette in the field referred to as “narratology”2 represents one of the most important contributions to narrative theory, considered as a branch of literary theory, in the second half of the twentieth century. I purposely say “one of the most important”, as there are other theoretical contributions, some of which I believe to be equally important though they are not as well known as Genette’s narratology, particularly in France.3 These lesser-known theories are rich in epis- temological reflection. -

ELEMENTS of FICTION – NARRATOR / NARRATIVE VOICE Fundamental Literary Terms That Indentify Components of Narratives “Fiction

Dr. Hallett ELEMENTS OF FICTION – NARRATOR / NARRATIVE VOICE Fundamental Literary Terms that Indentify Components of Narratives “Fiction” is defined as any imaginative re-creation of life in prose narrative form. All fiction is a falsehood of sorts because it relates events that never actually happened to people (characters) who never existed, at least not in the manner portrayed in the stories. However, fiction writers aim at creating “legitimate untruths,” since they seek to demonstrate meaningful insights into the human condition. Therefore, fiction is “untrue” in the absolute sense, but true in the universal sense. Critical Thinking – analysis of any work of literature – requires a thorough investigation of the “who, where, when, what, why, etc.” of the work. Narrator / Narrative Voice Guiding Question: Who is telling the story? …What is the … Narrative Point of View is the perspective from which the events in the story are observed and recounted. To determine the point of view, identify who is telling the story, that is, the viewer through whose eyes the readers see the action (the narrator). Consider these aspects: A. Pronoun p-o-v: First (I, We)/Second (You)/Third Person narrator (He, She, It, They] B. Narrator’s degree of Omniscience [Full, Limited, Partial, None]* C. Narrator’s degree of Objectivity [Complete, None, Some (Editorial?), Ironic]* D. Narrator’s “Un/Reliability” * The Third Person (therefore, apparently Objective) Totally Omniscient (fly-on-the-wall) Narrator is the classic narrative point of view through which a disembodied narrative voice (not that of a participant in the events) knows everything (omniscient) recounts the events, introduces the characters, reports dialogue and thoughts, and all details.