Shall We Dance? Lawrence University Symphony Orchestra, March 10, 2017 Lawrence University

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

ST. LOUIS SYMPHONY DAVID ROBERTSON, CONDUCTOR Wednesday, March 29, 2017, at 7:30Pm Foellinger Great Hall PROGRAM ST

ST. LOUIS SYMPHONY DAVID ROBERTSON, CONDUCTOR Wednesday, March 29, 2017, at 7:30pm Foellinger Great Hall PROGRAM ST. LOUIS SYMPHONY David Robertson, music director and conductor John Adams The Chairman Dances, Foxtrot for Orchestra (1985) (b. 1947) Aaron Copland Appalachian Spring, Ballet Suite for Orchestra (1944) (1900–1990) 20-minute intermission Ludwig van Beethoven Symphony No. 7 in A major, op. 92 (1812) (1770–1827) Poco sostenuto; Vivace Allegretto Presto; Assai meno Allegro con brio 2 THANK YOU TO THE SPONSORS OF THIS PERFORMANCE GIVING OF ACT THE Krannert Center honors the spirited generosity of these committed sponsors whose support of this performance continues to strengthen the impact of the arts in our community. Krannert Center honors the memory of Endowed Underwriters Marilyn Pflederer Zimmerman & Vernon K. Zimmerman. Their lasting investment in the performing arts and our community will allow future generations to experience world-class performances such as this one. * Krannert Center gratefully acknowledges the continued generosity of Endowed Sponsors Mary & Kenneth Andersen. With their previous sponsorships, they demonstrate their dedication to sharing beautiful and significant cultural events with our community. *PHOTO CREDIT: ILLINI STUDIO 3 * * JAMES ECONOMY HELEN & DANIEL RICHARDS Special Support of Classical Music Twenty-Seven Previous Sponsorships * * THE ACT OF GIVING OF ACT THE PEGGY MADDEN & MARY SCHULER & RICHARD PHILLIPS STEPHEN SLIGAR Fourteen Previous Sponsorships Five Previous Sponsorships Two Current Sponsorships -

Mcallister Interview Transcription

Interview with Timothy McAllister: Gershwin, Adams, and the Orchestral Saxophone with Lisa Keeney Extended Interview In September 2016, the University of Michigan’s University Symphony Orchestra (USO) performed a concert program with the works of two major American composers: John Adams and George Gershwin. The USO premiered both the new edition of Concerto in F and the Unabridged Edition of An American in Paris created by the UM Gershwin Initiative. This program also featured Adams’ The Chairman Dances and his Saxophone Concerto with soloist Timothy McAllister, for whom the concerto was written. This interview took place in August 2016 as a promotion for the concert and was published on the Gershwin Initiative’s YouTube channel with the help of Novus New Music, Inc. The following is a full transcription of the extended interview, now available on the Gershwin channel on YouTube. Dr. Timothy McAllister is the professor of saxophone at the University of Michigan. In addition to being the featured soloist of John Adams’ Saxophone Concerto, he has been a frequent guest with ensembles such as the Chicago Symphony Orchestra and the Los Angeles Philharmonic. Lisa Keeney is a saxophonist and researcher; an alumna of the University of Michigan, she works as an editing assistant for the UM Gershwin Initiative and also independently researches Gershwin’s relationship with the saxophone. ORCHESTRAL SAXOPHONE LK: Let’s begin with a general question: what is the orchestral saxophone, and why is it considered an anomaly or specialty instrument in orchestral music? TM: It’s such a complicated past that we have with the saxophone. -

Form in the Music of John Adams

Graduate Theses, Dissertations, and Problem Reports 2018 Form in the Music of John Adams Michael Ridderbusch Follow this and additional works at: https://researchrepository.wvu.edu/etd Recommended Citation Ridderbusch, Michael, "Form in the Music of John Adams" (2018). Graduate Theses, Dissertations, and Problem Reports. 6503. https://researchrepository.wvu.edu/etd/6503 This Dissertation is protected by copyright and/or related rights. It has been brought to you by the The Research Repository @ WVU with permission from the rights-holder(s). You are free to use this Dissertation in any way that is permitted by the copyright and related rights legislation that applies to your use. For other uses you must obtain permission from the rights-holder(s) directly, unless additional rights are indicated by a Creative Commons license in the record and/ or on the work itself. This Dissertation has been accepted for inclusion in WVU Graduate Theses, Dissertations, and Problem Reports collection by an authorized administrator of The Research Repository @ WVU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Form in the Music of John Adams Michael Ridderbusch DMA Research Paper submitted to the College of Creative Arts at West Virginia University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Musical Arts in Music Theory and Composition Andrew Kohn, Ph.D., Chair Travis D. Stimeling, Ph.D. Melissa Bingmann, Ph.D. Cynthia Anderson, MM Matthew Heap, Ph.D. School of Music Morgantown, West Virginia 2017 Keywords: John Adams, Minimalism, Phrygian Gates, Century Rolls, Son of Chamber Symphony, Formalism, Disunity, Moment Form, Block Form Copyright ©2017 by Michael Ridderbusch ABSTRACT Form in the Music of John Adams Michael Ridderbusch The American composer John Adams, born in 1947, has composed a large body of work that has attracted the attention of many performers and legions of listeners. -

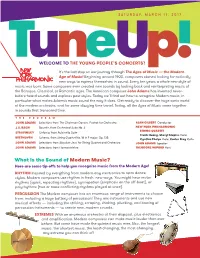

What Is the Sound of Modern Music?

SATURDAY, MARCH 11, 2017 Mozart’s “Classical” European tour? A TuWELCOMEn TO THE YOUNGe PEOPLE’SU CONCERTS!TM p! It’s the last stop on our journey through The Ages of Music — the Modern Age of Music! Beginning around 1900, composers started looking for radically new ways to express themselves in sound. Every ten years a whole new style of music was born. Some composers even created new sounds by looking back and reinterpreting music of the Baroque, Classical, or Romantic ages. The American composer John Adams has invented never- before-heard sounds and explores past styles. Today we’ll find out how to recognize Modern music, in particular what makes Adams’s music sound the way it does. Get ready to discover the huge sonic world of the modern orchestra, and for some dizzying time travel. Today, all the Ages of Music come together in sounds that transcend time. THE PROGRAM JOHN ADAMS Selections from The Chairman Dances, Foxtrot for Orchestra ALAN GILBERT Conductor J.S. BACH Bourrée, from Orchestral Suite No. 3 NEW YORK PHILHARMONIC STRING QUARTET STRAVINSKY Sinfonia, from Pulcinella Suite Frank Huang, Sheryl Staples Violin BEETHOVEN Scherzo, from String Quartet No. 16 in F major, Op. 135 Cynthia Phelps Viola; Carter Brey Cello JOHN ADAMS Selections from Absolute Jest, for String Quartet and Orchestra JOHN ADAMS Speaker JOHN ADAMS Selections from Harmonielehre THEODORE WIPRUD Host What Is the Sound of Modern Music? Here are some tip-offs to help you recognize music from the Modern Age! RHYTHM Inspired by everything from modern-day electronics to retro dance styles, Modern composers use rhythm in fresh, new ways. -

Harmonic Vocabulary in the Music of John Adams: a Hierarchical Approach Author(S): Timothy A

Yale University Department of Music Harmonic Vocabulary in the Music of John Adams: A Hierarchical Approach Author(s): Timothy A. Johnson Source: Journal of Music Theory, Vol. 37, No. 1 (Spring, 1993), pp. 117-156 Published by: Duke University Press on behalf of the Yale University Department of Music Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/843946 Accessed: 06-07-2017 19:50 UTC JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at http://about.jstor.org/terms Yale University Department of Music, Duke University Press are collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to Journal of Music Theory This content downloaded from 198.199.32.254 on Thu, 06 Jul 2017 19:50:30 UTC All use subject to http://about.jstor.org/terms HARMONIC VOCABULARY IN THE MUSIC OF JOHN ADAMS: A HIERARCHICAL APPROACH Timothy A. Johnson Overview Following the minimalist tradition, much of John Adams's' music consists of long passages employing a single set of pitch classes (pcs) usually encompassed by one diatonic set.2 In many of these passages the pcs form a single diatonic triad or seventh chord with no additional pcs. In other passages textural and registral formations imply a single triad or seventh chord, but additional pcs obscure this chord to some degree. -

Performances from 1974 to 2020

Performances from 1974 to 2020 2019-20 December 1 & 2, 2018 Michael Slon, Conductor September 28 & 29, 2019 Family Holiday Concerts Benjamin Rous, Conductor MOZART Symphony No. 32 February 16 & 17, 2019 ROUSTOM Ramal Benjamin Rous, Conductor BRAHMS Piano Concerto No. 2 in B-flat Major RAVEL Pavane pour une infante défunte RAVEL Piano Concerto in G Major November 16 & 17, 2019 MOYA Siempre Lunes, Siempre Marzo Benjamin Rous & Michael Slon, Conductors KODALY Variations on a HunGarian FolksonG MONTGOMERY Caught by the Wind ‘The Peacock’ RICHARD STRAUSS Horn Concerto No. 1 in E-flat Major March 23 & 24, 2019 MENDELSSOHN Psalm 42 Benjamin Rous, Conductor BRUCKNER Te Deum in C Major BARTOK Violin Concerto No. 2 MENDELSSOHN Symphony No. 4 in A Major December 6 & 7, 2019 Michael Slon, Conductor April 27 & 28, 2019 Family Holiday Concerts Benjamin Rous, Conductor WAGNER Prelude from Parsifal February 15 & 16, 2020 SCHUMANN Piano Concerto in A minor Benjamin Rous, Conductor SHATIN PipinG the Earth BUTTERWORTH A Shropshire Lad RESPIGHI Pines of Rome BRITTEN Nocturne GRACE WILLIAMS Elegy for String Orchestra June 1, 2019 VAUGHAN WILLIAMS On Wenlock Edge Benjamin Rous, Conductor ARNOLD Tam o’Shanter Overture Pops at the Paramount 2018-19 2017-18 September 29 & 30, 2018 September 23 & 24, 2017 Benjamin Rous, Conductor Benjamin Rous, Conductor BOWEN Concerto in C minor for Viola WALKER Lyric for StrinGs and Orchestra ADAMS Short Ride in a Fast Machine MUSGRAVE SonG of the Enchanter MOZART Clarinet Concerto in A Major SIBELIUS Symphony No. 2 in D Major BEETHOVEN Symphony No. 7 in A Major November 17 & 18, 2018 October 6, 2017 Damon Gupton, Conductor Michael Slon, Conductor ROSSINI Overture to Semiramide UVA Bicentennial Celebration BARBER Violin Concerto WALKER Lyric for StrinGs TCHAIKOVSKY Symphony No. -

Orchestra Repertoire by Composer

Concord Orchestra (1969-2019 seasons) –– Richard Pittman, 50th season as conductor by Composer Compiled by Grant Anderson, June 2019 1 Concord Orchestra Repertoire by Composer (1969-2019 seasons) — Richard Pittman, conductor Composer Composition Composed Soloists Groups Concert Adams John (1947 – ) Nixon in China: The Chairman Dances 1985 May 2000 Adams John (1947 – ) ShortA Short Ride in a Fast Machine (Fanfare for 1986 December 1990 Great Woods) Adams John (1947 – ) AShort Short Ride in a Fast Machine (Fanfare for 1986 December 2000 Great Woods) Adler Samuel (1928 – ) TheFlames Flames of Freedom: Ma’oz Tzur (Rock 1982 Lexington High School December 2015 of Ages), Mi y’mallel (Who Can Retell?) Women’s Chorus (Jason Iannuzzi) Albéniz Isaac (1860 – 1909) Suite española, Op. 47: Granada & Sevilla 1886 May 2016 Albert Stephen (1941 – 1992) River-Run: Rain Music, River's End 1984 October 1986 Alford, born Kenneth, born (1881 – 1945) Colonel Bogey March 1914 May 1994 Ricketts Frederick Anderson Leroy (1908 – 1975) Belle of the Ball 1951 May 1998 Anderson Leroy (1908 – 1975) Belle of the Ball 1951 July 1998 Anderson Leroy (1908 – 1975) Belle of the Ball 1951 May 2003 Anderson Leroy (1908 – 1975) Blue Tango 1951 May 1998 Anderson Leroy (1908 – 1975) Blue Tango 1951 May 2007 Anderson Leroy (1908 – 1975) Blue Tango 1951 May 2011 Anderson Leroy (1908 – 1975) BuglerA Bugler's Holiday 1954 Norman Plummer, April 1971 Thomas Taylor, Stanley Schultz trumpet Anderson Leroy (1908 – 1975) BuglerA Bugler's Holiday 1954f John Ossi, James May 1979 Dolham, -

AS Level Performance Studies Topic Exploration Pack (John Adams)

Performance Studies A LEVEL Performance Studies: John Adams Topic Exploration Pack September 2015 www.ocr.org.uk Topic Exploration Pack We will inform centres about any changes to the specification. We will also publish changes on our website. The latest version of our specification will always be the one on our website (www.ocr.org.uk) and this may differ from printed versions. Copyright © 2015 OCR. All rights reserved. Copyright OCR retains the copyright on all its publications, including the specifications. However, registered centres for OCR are permitted to copy material from this specification booklet for their own internal use. Oxford Cambridge and RSA Examinations is a Company Limited by Guarantee. Registered in England. Registered company number 3484466. Registered office: 1 Hills Road Cambridge CB1 2EU OCR is an exempt charity. 2 www.ocr.org.uk AS Level Performance Studies Contents John Adams Teacher Resource Pack ............................................................................................. 4 Background ..................................................................................................................................... 5 Adams’ Works ................................................................................................................................. 5 Fingerprints of Adams’ Style ........................................................................................................... 7 Influences ...................................................................................................................................... -

Traficante Final Dissertation

UNIVERSITY OF OKLAHOMA GRADUATE COLLEGE AN ANALYSIS OF JOHN ADAMS’ GRAND PIANOLA MUSIC A DOCUMENT SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUATE FACULTY in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of DOCTOR OF MUSICAL ARTS By DEBRA LEE TRAFICANTE Norman, Oklahoma 2010 AN ANALYSIS OF JOHN ADAMS’ GRAND PIANOLA MUSIC A DOCUMENT APPROVED FOR THE SCHOOL OF MUSIC BY ________________________________ Dr. William K. Wakefield, Chair ________________________________ Dr. Roland Barrett ________________________________ Dr. Paula Conlon ________________________________ Dr. Michael Raiber ________________________________ Dr. Teresa DeBacker © Copyright by DEBRA LEE TRAFICANTE 2010 All Rights Reserved. ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS My document committee consists of Dr. William K. Wakefield, Dr. Roland Barrett, Dr. Michael Raiber, Dr. Paula Conlon, and Dr. Teresa DeBacker, and I thank each of them for their careful reading and great assistance in the execution of this document. I feel very fortunate to have had the members who served on this committee, and hold them each in high regard. Special thanks are especially due to Dr. Wakefield, chair of my committee; he tirelessly helped me clarify ideas, find new ways to experience the piece, and express my thoughts more cogently. Without his unremitting support, this document would not exist. To my parents, Ron and Mary Ann Manna, I owe any success I have ever achieved to you both. The never-ending support you have afforded me is why I have accomplished what I have. I love you both and thank you. To my in-laws, Harry and Cheryl Craig, I sincerely appreciate the endless love and support you have given to me for the last fifteen years. -

Seeking Peace of Mind About Your Estate and Family?

MATINEE 4 Seeking peace of mind about your estate and family? FRIDAY 25 NOVEMBER 2.30PM FEDERATION CONCERT HALL HOBART Marko Letonja conductor GERSHWIN Andrew Seymour clarinet Catfish Row: Symphonic Suite from ADAMS Porgy and Bess The Chairman Dances Catfish Row Duration 12 mins Porgy Sings Fugue COPLAND Hurricane Clarinet Concerto Good Morning, Sistuh Slowly and expressively – Duration 24 mins Cadenza – Rather fast This concert will end at approximately 4.30pm. Duration 17 mins INTERVAL Expert advice Duration 20 mins and solutions. MUNRO Blue Rags Bad Girl Rag Tromba Blues Sponsored by China Rag Duration 12 mins Tasmanian Symphony Orchestra concerts are broadcast and streamed throughout Australia and around the world by ABC Classic FM. We would appreciate your cooperation in keeping coughing to a minimum. Please ensure that your mobile phone is switched off. 48 49 JOHN ADAMS (born 1947) The Chairman Dances – Foxtrot for In the surreal final scene of the opera, Orchestra she interrupts the tired formalities of a state banquet, disrupts the slow moving American John Adams is one of the most protocol and invites the Chairman, who successful composers working today. He first is present only as a gigantic 40-foot came to prominence in the early 1980s with portrait on the wall, to “come down, works such as Harmonium, Grand Pianola MARKO LETONJA ANDREW SEYMOUR old man, and dance”. The music takes Music and Harmonielehre, and achieved full cognisance of her past as a movie even greater success with the opera Nixon actress. Themes, sometimes slinky and in China, which he wrote in collaboration Marko Letonja is Chief Conductor Principal Clarinet with the Tasmanian sentimental, at other times bravura and with poet Alice Goodman and stage director and Artistic Director of the Tasmanian Symphony Orchestra since 2012, Andrew bounding, ride above in bustling fabric Peter Sellars. -

Los Angeles Master Chorale to Celebrate Composer John Adams' 70Th

PRESS RELEASE LOS ANGELES MASTER CHORALE TO CELEBRATE COMPOSER JOHN ADAMS’ 70TH BIRTHDAY WITH PERFORMANCE OF STRAVINSKY’S LES NOCES & CHORUSES FROM FIVE ADAMS OPERAS 115-member chorus conducted by Artistic Director Grant Gershon Soloists Elissa Johnston, Peabody Southwell, Todd Strange, and Nicholas Brownlee; pianists Gloria Cheng, Lisa Edwards, Bryan Pezzone, and Vicki Ray; and percussionists Theresa Dimond, John Wakefield, Scott Higgins, Judy Chilnick, Alex Frederick, and Gary Heaton-Smith Premiere performance of new piano transcriptions by Chitose Okashiro, curated for Boosey & Hawkes by Gershon, of choruses from The Gospel According to the Other Mary, The Death of Klinghoffer, Doctor Atomic, A Flowering Tree, and Nixon in China SUNDAY, MARCH 26 AT 7 PM WALT DISNEY CONCERT HALL 1 3 5 N O R T H G R A N D AV E N U E , LO S A N G E L E S , C A L I F O R N I A 9 0 0 1 2 - -- 3 0 1 3 2 1 3 - 9 7 2 - 3 1 2 2 | L A M A ST E R C H O R A L E . O R G STRAVINSKY & JOHN ADAMS, PAGE 2 (Los Angeles, CA, February 2, 2017) – There will be an exuberant musical celebration in Walt Disney Concert Hall on Sunday, March 26 when the Los Angeles Master Chorale and Artistic Director Grant Gershon celebrate composer John Adams’ 70th birthday with Les Noces, Stravinsky’s raucous depiction of a 19th-century Russian peasant wedding. The concert will open with the premiere of 10 new piano transcriptions of choruses from Adams operas by noted Japanese pianist Chitose Okashiro, curated by Gershon, for music publisher Boosey & Hawkes. -

Tournament 10 Round #7

Tournament 10 Round 7 Tossups 1. This artist painted Jesus floating above an altar, while doctors of the church and saints like Thomas Aquinas discuss the Eucharist, in one of the Pope’s stanzae. That work, The Disputation of the Sacrament, is found in the same building as a work of this painter that shows (*) Plato holding his Timaeus. He painted Pythagoras, Aristotle, Diogenes, and Heraclitus in one work. Two contemplative putti, or angels, appear at the bottom of his Sistine Madonna. For 10 points, name this Renaissance painter of The School of Athens. ANSWER: Raphael [or Raffaello Sanzio; or Raffaello Santi] 027-09-11-07102 2. The death of this character causes the observation "Life's but a walking shadow." This character references the "poor cat in the adage" while trying to convince another character to go through with her plan. After reading a letter, this character asks the "spirits that tend on mortal thoughts" to "unsex me here." In her last appearance, she (*) washes her hands while sleepwalking and proclaims, "Out, damned spot! Out, I say!" For 10 points, name this character who convinces her titular husband to murder Duncan in a Shakespeare play. ANSWER: Lady Macbeth [do not accept or prompt on "Macbeth"] 003-09-11-07103 3. This thinker encouraged American intellectuals to be less subservient to politics in his essay "The Responsibility of Intellectuals." He proposed a gap between the exposure of children to language and the rate and depth at which they learn language, which he called "the poverty of the stimulus." This (*) linguist originated the theory of transformational-generative grammar in Syntactic Structures and composed the meaningless but grammatically correct sentence "colorless green ideas sleep furiously." For 10 points, name this MIT linguist.