MC Trey: the 'Feline Force' of Australian Hip Hop Tony Mitchell

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Working-Class Experience in Contemporary Australian Poetry

The Working-Class Experience in Contemporary Australian Poetry A thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Sarah Attfield BCA (Hons) University of Technology, Sydney August 2007 i Acknowledgements Before the conventional thanking of individuals who have assisted in the writing of this thesis, I want to acknowledge my class background. Completing a PhD is not the usual path for someone who has grown up in public housing and experienced childhood as a welfare dependent. The majority of my cohort from Chingford Hall Estate did not complete school beyond Year 10. As far as I am aware, I am the only one among my Estate peers to have a degree and definitely the only one to have attempted a PhD. Having a tertiary education has set me apart from my peers in many ways, and I no longer live on the Estate (although my mother and old neighbours are still there). But when I go back to visit, my old friends and neighbours are interested in my education and they congratulate me on my achievements. When I explain that I’m writing about people like them – about stories they can relate to, they are pleased. The fact that I can discuss my research with my family, old school friends and neighbours is really important. If they couldn’t understand my work there would be little reason for me to continue. My life has been shaped by my class. It has affected my education, my opportunities and my outlook on life. I don’t look back at the hardship with a fuzzy sense of nostalgia, and I will be forever angry at the class system that held so many of us back, but I am proud of my working-class family, friends and neighbourhood. -

Marc Brennan Thesis

Writing to Reach You: The Consumer Music Press and Music Journalism in the UK and Australia Marc Brennan, BA (Hons) Creative Industries Research and Applications Centre (CIRAC) Thesis Submitted for the Completion of Doctor of Philosophy (Creative Industries), 2005 Writing to Reach You Keywords Journalism, Performance, Readerships, Music, Consumers, Frameworks, Publishing, Dialogue, Genre, Branding Consumption, Production, Internet, Customisation, Personalisation, Fragmentation Writing to Reach You: The Consumer Music Press and Music Journalism in the UK and Australia The music press and music journalism are rarely subjected to substantial academic investigation. Analysis of journalism often focuses on the production of news across various platforms to understand the nature of politics and public debate in the contemporary era. But it is not possible, nor is it necessary, to analyse all emerging forms of journalism in the same way for they usually serve quite different purposes. Music journalism, for example, offers consumer guidance based on the creation and maintenance of a relationship between reader and writer. By focusing on the changing aspects of this relationship, an analysis of music journalism gives us an understanding of the changing nature of media production, media texts and media readerships. Music journalism is dialogue. It is a dialogue produced within particular critical frameworks that speak to different readers of the music press in different ways. These frameworks are continually evolving and reflect the broader social trajectory in which music journalism operates. Importantly, the evolving nature of music journalism reveals much about the changing consumption of popular music. Different types of consumers respond to different types of guidance that employ a variety of critical approaches. -

Television Academy Awards

2021 Primetime Emmy® Awards Ballot Outstanding Music Composition For A Series (Original Dramatic Score) The Alienist: Angel Of Darkness Belly Of The Beast After the horrific murder of a Lying-In Hospital employee, the team are now hot on the heels of the murderer. Sara enlists the help of Joanna to tail their prime suspect. Sara, Kreizler and Moore try and put the pieces together. Bobby Krlic, Composer All Creatures Great And Small (MASTERPIECE) Episode 1 James Herriot interviews for a job with harried Yorkshire veterinarian Siegfried Farnon. His first day is full of surprises. Alexandra Harwood, Composer American Dad! 300 It’s the 300th episode of American Dad! The Smiths reminisce about the funniest thing that has ever happened to them in order to complete the application for a TV gameshow. Walter Murphy, Composer American Dad! The Last Ride Of The Dodge City Rambler The Smiths take the Dodge City Rambler train to visit Francine’s Aunt Karen in Dodge City, Kansas. Joel McNeely, Composer American Gods Conscience Of The King Despite his past following him to Lakeside, Shadow makes himself at home and builds relationships with the town’s residents. Laura and Salim continue to hunt for Wednesday, who attempts one final gambit to win over Demeter. Andrew Lockington, Composer Archer Best Friends Archer is head over heels for his new valet, Aleister. Will Archer do Aleister’s recommended rehabilitation exercises or just eat himself to death? JG Thirwell, Composer Away Go As the mission launches, Emma finds her mettle as commander tested by an onboard accident, a divided crew and a family emergency back on Earth. -

Song List 2012

SONG LIST 2012 www.ultimamusic.com.au [email protected] (03) 9942 8391 / 1800 985 892 Ultima Music SONG LIST Contents Genre | Page 2012…………3-7 2011…………8-15 2010…………16-25 2000’s…………26-94 1990’s…………95-114 1980’s…………115-132 1970’s…………133-149 1960’s…………150-160 1950’s…………161-163 House, Dance & Electro…………164-172 Background Music…………173 2 Ultima Music Song List – 2012 Artist Title 360 ft. Gossling Boys Like You □ Adele Rolling In The Deep (Avicii Remix) □ Adele Rolling In The Deep (Dan Clare Club Mix) □ Afrojack Lionheart (Delicious Layzas Moombahton) □ Akon Angel □ Alyssa Reid ft. Jump Smokers Alone Again □ Avicii Levels (Skrillex Remix) □ Azealia Banks 212 □ Bassnectar Timestretch □ Beatgrinder feat. Udachi & Short Stories Stumble □ Benny Benassi & Pitbull ft. Alex Saidac Put It On Me (Original mix) □ Big Chocolate American Head □ Big Chocolate B--ches On My Money □ Big Chocolate Eye This Way (Electro) □ Big Chocolate Next Level Sh-- □ Big Chocolate Praise 2011 □ Big Chocolate Stuck Up F--k Up □ Big Chocolate This Is Friday □ Big Sean ft. Nicki Minaj Dance Ass (Remix) □ Bob Sinclair ft. Pitbull, Dragonfly & Fatman Scoop Rock the Boat □ Bruno Mars Count On Me □ Bruno Mars Our First Time □ Bruno Mars ft. Cee Lo Green & B.O.B The Other Side □ Bruno Mars Turn Around □ Calvin Harris ft. Ne-Yo Let's Go □ Carly Rae Jepsen Call Me Maybe □ Chasing Shadows Ill □ Chris Brown Turn Up The Music □ Clinton Sparks Sucks To Be You (Disco Fries Remix Dirty) □ Cody Simpson ft. Flo Rida iYiYi □ Cover Drive Twilight □ Datsik & Kill The Noise Lightspeed □ Datsik Feat. -

Interview with MO Just Say

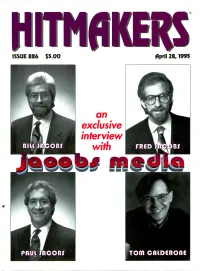

ISSUE 886 $5.00 flpril 28, 1995 an exclusive interview with MO Just Say... VEDA "I Saw You Dancing" GOING FOR AIRPLAY NOW Written and Produced by Jonas Berggren of Ace OF Base 132 BDS DETECTIONS! SPINNING IN THE FIRST WEEK! WJJS 19x KBFM 30x KLRZ 33x WWCK 22x © 1995 Mega Scandinavia, Denmark It means "cheers!" in welsh! ISLAND TOP40 Ra d io Multi -Format Picks Based on this week's EXCLUSIVE HITMEKERS CONFERENCE CELLS and ONE-ON-ONE calls. ALL PICKS ARE LISTED IN ALPHABETICAL ORDER. MAINSTREAM 4 P.M. Lay Down Your Love (ISLAND) JULIANA HATFIELD Universal Heartbeat (ATLANTIC) ADAM ANT Wonderful (CAPITOL) MATTHEW SWEET Sick Of Myself (ZOO) ADINA HOWARD Freak Like Me (EASTWEST/EEG) MONTELL JORDAN This Is How...(PMP/RAL/ISLAND) BOYZ II MEN Water Runs Dry (MOTOWN) M -PEOPLE Open Up Your Heart (EPIC) BRUCE SPRINGSTEEN Secret Garden (COLUMBIA) NICKI FRENCH Total Eclipse Of The Heart (CRITIQUE) COLLECTIVE SOUL December (ATLANTIC) R.E.M. Strange Currencies (WARNER BROS.) CORONA Baby Baby (EASTWEST/EEG) SHAW BLADES I'll Always Be With You (WARNER BROS.) DAVE MATTHEWS What Would You Say (RCA) SIMPLE MINDS Hypnotised (VIRGIN) DAVE STEWART Jealousy (EASTWEST/EEG) TECHNOTRONIC Move It To The Rhythm (EMI RECORDS) DIANA KING Shy Guy (WORK GROUP) ELASTICA Connection (GEFFEN) THE JAYHAWKS Blue (AMERICAN) GENERAL PUBLIC Rainy Days (EPIC) TOM PETTY It's Good To Be King (WARNER BRCS.) JON B. AND BABYFACE Someone To Love (YAB YUM/550) VANESSA WILLIAMS The Way That You Love (MERCURY) STREET SHEET 2PAC Dear Mama INTERSCOPE) METHOD MAN/MARY J. BIJGE I'll Be There -

![COMPLETE MUSIC LIST by ARTIST ] [ No of Tunes = 6773 ]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/5125/complete-music-list-by-artist-no-of-tunes-6773-465125.webp)

COMPLETE MUSIC LIST by ARTIST ] [ No of Tunes = 6773 ]

[ COMPLETE MUSIC LIST by ARTIST ] [ No of Tunes = 6773 ] 001 PRODUCTIONS >> BIG BROTHER THEME 10CC >> ART FOR ART SAKE 10CC >> DREADLOCK HOLIDAY 10CC >> GOOD MORNING JUDGE 10CC >> I'M NOT IN LOVE {K} 10CC >> LIFE IS A MINESTRONE 10CC >> RUBBER BULLETS {K} 10CC >> THE DEAN AND I 10CC >> THE THINGS WE DO FOR LOVE 112 >> DANCE WITH ME 1200 TECHNIQUES >> KARMA 1910 FRUITGUM CO >> SIMPLE SIMON SAYS {K} 1927 >> IF I COULD {K} 1927 >> TELL ME A STORY 1927 >> THAT'S WHEN I THINK OF YOU 24KGOLDN >> CITY OF ANGELS 28 DAYS >> SONG FOR JASMINE 28 DAYS >> SUCKER 2PAC >> THUGS MANSION 3 DOORS DOWN >> BE LIKE THAT 3 DOORS DOWN >> HERE WITHOUT YOU {K} 3 DOORS DOWN >> KRYPTONITE {K} 3 DOORS DOWN >> LOSER 3 L W >> NO MORE ( BABY I'M A DO RIGHT ) 30 SECONDS TO MARS >> CLOSER TO THE EDGE 360 >> LIVE IT UP 360 >> PRICE OF FAME 360 >> RUN ALONE 360 FEAT GOSSLING >> BOYS LIKE YOU 3OH!3 >> DON'T TRUST ME 3OH!3 FEAT KATY PERRY >> STARSTRUKK 3OH!3 FEAT KESHA >> MY FIRST KISS 4 THE CAUSE >> AIN'T NO SUNSHINE 4 THE CAUSE >> STAND BY ME {K} 4PM >> SUKIYAKI 5 SECONDS OF SUMMER >> DON'T STOP 5 SECONDS OF SUMMER >> GIRLS TALK BOYS {K} 5 SECONDS OF SUMMER >> LIE TO ME {K} 5 SECONDS OF SUMMER >> SHE LOOKS SO PERFECT 5 SECONDS OF SUMMER >> SHE'S KINDA HOT {K} 5 SECONDS OF SUMMER >> TEETH 5 SECONDS OF SUMMER >> WANT YOU BACK 5 SECONDS OF SUMMER >> YOUNGBLOOD {K} 50 CENT >> 21 QUESTIONS 50 CENT >> AYO TECHNOLOGY 50 CENT >> CANDY SHOP 50 CENT >> IF I CAN'T 50 CENT >> IN DA CLUB 50 CENT >> P I M P 50 CENT >> PLACES TO GO 50 CENT >> WANKSTA 5000 VOLTS >> I'M ON FIRE 5TH DIMENSION -

High-Fidelity-1955-Nov.Pdf

November 60 cents SIBELIUS AT 90 by Gerald Abraham A SIBELIUS DISCOGRAPHY by Paul Affelder www.americanradiohistory.com FOR FINE SOUND ALL AROUND Bob Fine, of gt/JZe lwtCL ., has standardized on C. Robert Fine, President, and Al Mian, Chief Mixer, at master con- trol console of Fine Sound, Inc., 711 Fifth Ave., New York City. because "No other sound recording the finest magnetic recording tape media hare been found to meet our exact - you can buy - known the world over for its outstanding performance ing'requirements for consistent, uniform and fidelity of reproduction. Now avail- quality." able on 1/2-mil, 1 -mil and 11/2-mil polyester film base, as well as standard plastic base. In professional circles Bob Fine is a name to reckon auaaaa:.cs 'exceed the most with. His studio, one of the country's largest and exacting requirements for highest quality professional recordings. Available in sizes best equipped, cuts the masters for over half the and types for every disc recording applica- records released each year by independent record lion. manufacturers. Movies distributed throughout the magnetically coated world, filmed TV broadcasts, transcribed radio on standard motion picture film base, broadcasts, and advertising transcriptions are re- provides highest quality synchronized re- corded here at Fine Sound, Inc., on Audio products. cordings for motion picture and TV sound tracks. Every inch of tape used here is Audiotape. Every disc cut is an Audiodisc. And now, Fine Sound is To get the most out of your sound recordings, now standardizing on Audiofilm. That's proof of the and as long as you keep them, be sure to put them consistent, uniform quality of all Audio products: on Audiotape, Audiodiscs or Audiofilm. -

Individuality, Collectivity, and Samoan Artistic Responses to Cultural Change

The I and the We: Individuality, Collectivity, and Samoan Artistic Responses to Cultural Change April K Henderson That the Samoan sense of self is relational, based on socio-spatial rela- tionships within larger collectives, is something of a truism—a statement of such obvious apparent truth that it is taken as a given. Tui Atua Tupua Tamasese Taisi Efi, a former prime minister and current head of state of independent Sāmoa as well as an influential intellectual and essayist, has explained this Samoan relational identity: “I am not an individual; I am an integral part of the cosmos. I share divinity with my ancestors, the land, the seas and the skies. I am not an individual, because I share a ‘tofi’ (an inheritance) with my family, my village and my nation. I belong to my family and my family belongs to me. I belong to my village and my village belongs to me. I belong to my nation and my nation belongs to me. This is the essence of my sense of belonging” (Tui Atua 2003, 51). Elaborations of this relational self are consistent across the different political and geographical entities that Samoans currently inhabit. Par- ticipants in an Aotearoa/New Zealand–based project gathering Samoan perspectives on mental health similarly described “the Samoan self . as having meaning only in relationship with other people, not as an individ- ual. This self could not be separated from the ‘va’ or relational space that occurs between an individual and parents, siblings, grandparents, aunts, uncles and other extended family and community members” (Tamasese and others 2005, 303). -

Bay Guardian | August 26 - September 1, 2009 ■

I Newsom screwed the city to promote his campaign for governor^ How hackers outwitted SF’s smart parking meters Pi2 fHB _ _ \i, . EDITORIALS 5 NEWS + CULTURE 8 PICKS 14 MUSIC 22 STAGE 40 FOOD + DRINK 45 LETTERS 5 GREEN CITY 13 FALL ARTS PREVIEW 16 VISUAL ART 38 LIT 44 FILM 48 1 I ‘ VOflj On wireless INTRODUCING THE BLACKBERRY TOUR BLACKBERRY RUNS BETTER ON AMERICA'S LARGEST, MOST RELIABLE 3G NETWORK. More reliable 3G coverage at home and on the go More dependable downloads on hundreds of apps More access to email and full HTML Web around the globe New from Verizon Wireless BlackBerryTour • Brilliant hi-res screen $ " • Ultra fast processor 199 $299.99 2-yr. price - $100 mail-in rebate • Global voice and data capabilities debit card. Requires new 2-yr. activation on a voice plan with email feature, or email plan. • Best camera on a full keyboard BlackBerry—3.2 megapixels DOUBLE YOUR BLACKBERRY: BlackBerry Storm™ Now just BUY ANY, GET ONE FREE! $99.99 Free phone 2-yr. price must be of equal or lesser value. All 2-yr. prices: Storm: $199.99 - $100 mail-in rebate debit card. Curve: $149.99 - $100 mail-in rebate debit card. Pearl Flip: $179.99 - $100 mail-in rebate debit card. Add'l phone $100 - $100 mail-in rebate debit card. All smartphones require new 2-yr. activation on a voice plan with email feature, or email plan. While supplies last. SWITCH TO AMERICA S LARGEST, MOST RELIABLE 3G NETWORK. Call 1.800.2JOIN.IN Click verizonwireless.com Visit any Communications Store to shop or find a store near you Activation fee/line: $35 ($25 for secondary Family SharePlan’ lines w/ 2-yr. -

Robert Hunter (Huntersbx) on Twitter

Robert Hunter (HunterSBX) on Twitter http://twitter.com/ Twitter Search Home Profile Messages Who To Follow AliaK Settings Help Switch to Old Twitter Sign out New Tweet Robert Hunter @HunterSBX Perth Western Australia Rapper, a parent to a Son named Marley. A cancer patient. That's what I am. Message Following Unfollow Timeline Favorites Following Followers Lists » HunterSBX Robert Hunter @ @I_Am_Simplex Kirks massive BBQ bonananza! Was just Trials, Daz, Kirk, me, a digital 1 of 134 20/04/11 1:50 PM Robert Hunter (HunterSBX) on Twitter http://twitter.com/ camera, 3 cartons of Pale. 21 minutes ago Favorite Retweet Reply » HunterSBX Robert Hunter @ @funkoars the confusion of being in a photo within a photo of your own penis is something that will always confuse me. #scaredofthedick 26 minutes ago Favorite Retweet Reply » HunterSBX Robert Hunter I didn't make, fund, or have anything to do with said Doco, I just consented to them following me around. I am honored that they did but. 31 minutes ago Favorite Retweet Reply » HunterSBX Robert Hunter @ @funkoars yeh no shit hey! That's an integral part of the whole picture! Hahah! I'm just glad they don't have too much footage of my penis 33 minutes ago Favorite Retweet Reply » HunterSBX Robert Hunter Check this video out -- Hunter: The Documentary (short teaser) youtube.com/watch?v=LVNc8b… via @youtube <~~ pretty strange feeling. 1 hour ago Unfavorite Undo Retweet Reply » HunterSBX Robert Hunter Exclusive: Drapht''s "Sing It (The Life of Riley)" music video - NovaFM Videos novafm.com.au/video_exclusiv… <-- good shit! 1 hour ago Favorite Retweet Reply » HunterSBX Robert Hunter Turned on the computer and lost all inspiration to write... -

Sooloos Collections: Advanced Guide

Sooloos Collections: Advanced Guide Sooloos Collectiions: Advanced Guide Contents Introduction ...........................................................................................................................................................3 Organising and Using a Sooloos Collection ...........................................................................................................4 Working with Sets ..................................................................................................................................................5 Organising through Naming ..................................................................................................................................7 Album Detail ....................................................................................................................................................... 11 Finding Content .................................................................................................................................................. 12 Explore ............................................................................................................................................................ 12 Search ............................................................................................................................................................. 14 Focus .............................................................................................................................................................. -

Byronecho2136.Pdf

THE BYRON SHIRE ECHO Advertising & news enquiries: Mullumbimby 02 6684 1777 Byron Bay 02 6685 5222 seven Fax 02 6684 1719 [email protected] [email protected] http://www.echo.net.au VOLUME 21 #36 TUESDAY, FEBRUARY 20, 2007 echo entertainment 22,300 copies every week Page 21 $1 at newsagents only YEAR OF THE FLYING PIG Fishheads team wants more time at Brothel approval Byron Bay swimming pool goes to court Michael McDonald seeking a declaration the always intended ‘to hold Rick and Gayle Hultgren, development consent was activities involving children’ owners of the Byron Enter- null and void. rather than as for car parking tainment Centre, are taking Mrs Hultgren said during as mentioned in the staff a class 4 action in the Land public access at Council’s report. and Environment Court meeting last Thursday that ‘Over 1,000 people have against Byron Shire Coun- councillors had not been expressed their serious con- cil’s approval of a brothel aware of all the issues cern in writing. Our back near their property in the involved when considering door is 64 metres away from Byron Arts & Industry the brothel development the brothel in a direct line of Estate. An initial court hear- application (DA). She said sight. Perhaps 200 metres ing was scheduled for last their vacant lot across the would be better [as a Council Friday, with the Hultgrens street from the brothel was continued on page 2 Fishheads proprietors Mark Sims and Ralph Mamone at the pool. Photo Jeff Dawson Paragliders off to world titles Michael McDonald dispute came to prominence requirement for capital The lessees of the Byron Bay again with Cr Bob Tardif works.