Use and Interpretation of Climate Envelope Models: a Practical Guide

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Single Sample Sequencing Data Sheet

Single sample sequencing service includes FREE - repeats for failed sequences (Flexi / Premium Run) - use of our Pick-up boxes at various locations Single sample sequencing - universal primers (Flexi / Premium Run) - LGC plasmid DNA standard (simply load and compare 2 μL (100 ng) of plasmid DNA standard to your plasmid preparation) - sample bags for secure sample shipment analytical quality • measur eme nt ac • Automated and standardised ABI 3730 XL cu ra sequencing run with a read length up to 1,100 nt c y (PHRED20 quality) • re g • Overnight turnaround if samples are delivered u la before 10 am t o r • Stored customer-specific primers are selectable y t during online ordering for 3 months e s t i • Return of aliquots of synthesised primers on request. n g • Expert advice and customer support on c h Tel: +49 (0)30 5304 2230 from 8 am to 6 pm e Monday to Friday m i c a l Online ordering system m e To place your order please visit our webpage and a s u log onto our online ordering system at r e https://shop.lgcgenomics.com m e n t • Register as a new user • b i • Choose your sequencing service, order labels, o a n manage your data and shipment order a l y s i s • Please prepare your samples according to the given • s t a n d a r d s • f o r e n s i c t e s t i n requirements and send your samples in a padded g envelope to us. -

The EMA Guide to Envelopes and Mailing

The EMA Guide to Envelopes & Mailing 1 Table of Contents I. History of the Envelope An Overview of Envelope Beginnings II. Introduction to the Envelope Envelope Construction and Types III. Standard Sizes and How They Originated The Beginning of Size Standardization IV. Envelope Construction, Seams and Flaps 1. Seam Construction 2. Glues and Flaps V. Selecting the Right Materials 1. Paper & Other Substrates 2. Window Film 3. Gums/Adhesives 4. Inks 5. Envelope Storage 6. Envelope Materials and the Environment 7. The Paper Industry and the Environment VI. Talking with an Envelope Manufacturer How to Get the Best Finished Product VII. Working with the Postal Service Finding the Information You Need VIII. Final Thoughts IX. Glossary of Terms 2 Forward – The EMA Guide to Envelopes & Mailing The envelope is only a folded piece of paper yet it is an important part of our national communications system. The power of the envelope is the power to touch someone else in a very personal way. The envelope has been used to convey important messages of national interest or just to say “hello.” It may contain a greeting card sent to a friend or relative, a bill or other important notice. The envelope never bothers you during the dinner hour nor does it shout at you in the middle of a television program. The envelope is a silent messenger – a very personal way to tell someone you care or get them interested in your product or service. Many people purchase envelopes over the counter and have never stopped to think about everything that goes into the production of an envelope. -

Food Packaging Technology

FOOD PACKAGING TECHNOLOGY Edited by RICHARD COLES Consultant in Food Packaging, London DEREK MCDOWELL Head of Supply and Packaging Division Loughry College, Northern Ireland and MARK J. KIRWAN Consultant in Packaging Technology London Blackwell Publishing © 2003 by Blackwell Publishing Ltd Trademark Notice: Product or corporate names may be trademarks or registered Editorial Offices: trademarks, and are used only for identification 9600 Garsington Road, Oxford OX4 2DQ and explanation, without intent to infringe. Tel: +44 (0) 1865 776868 108 Cowley Road, Oxford OX4 1JF, UK First published 2003 Tel: +44 (0) 1865 791100 Blackwell Munksgaard, 1 Rosenørns Allè, Library of Congress Cataloging in P.O. Box 227, DK-1502 Copenhagen V, Publication Data Denmark A catalog record for this title is available Tel: +45 77 33 33 33 from the Library of Congress Blackwell Publishing Asia Pty Ltd, 550 Swanston Street, Carlton South, British Library Cataloguing in Victoria 3053, Australia Publication Data Tel: +61 (0)3 9347 0300 A catalogue record for this title is available Blackwell Publishing, 10 rue Casimir from the British Library Delavigne, 75006 Paris, France ISBN 1–84127–221–3 Tel: +33 1 53 10 33 10 Originated as Sheffield Academic Press Published in the USA and Canada (only) by Set in 10.5/12pt Times CRC Press LLC by Integra Software Services Pvt Ltd, 2000 Corporate Blvd., N.W. Pondicherry, India Boca Raton, FL 33431, USA Printed and bound in Great Britain, Orders from the USA and Canada (only) to using acid-free paper by CRC Press LLC MPG Books Ltd, Bodmin, Cornwall USA and Canada only: For further information on ISBN 0–8493–9788–X Blackwell Publishing, visit our website: The right of the Author to be identified as the www.blackwellpublishing.com Author of this Work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. -

Plain Packaging of Cigarettes and Smoking Behavior

Maynard et al. Trials 2014, 15:252 http://www.trialsjournal.com/content/15/1/252 TRIALS STUDY PROTOCOL Open Access Plain packaging of cigarettes and smoking behavior: study protocol for a randomized controlled study Olivia M Maynard1,2,3*, Ute Leonards3, Angela S Attwood1,2,3, Linda Bauld2,4, Lee Hogarth5 and Marcus R Munafò1,2,3 Abstract Background: Previous research on the effects of plain packaging has largely relied on self-report measures. Here we describe the protocol of a randomized controlled trial investigating the effect of the plain packaging of cigarettes on smoking behavior in a real-world setting. Methods/Design: In a parallel group randomization design, 128 daily cigarette smokers (50% male, 50% female) will attend an initial screening session and be assigned plain or branded packs of cigarettes to smoke for a full day. Plain packs will be those currently used in Australia where plain packaging has been introduced, while branded packs will be those currently used in the United Kingdom. Our primary study outcomes will be smoking behavior (self-reported number of cigarettes smoked and volume of smoke inhaled per cigarette as measured using a smoking topography device). Secondary outcomes measured pre- and post-intervention will be smoking urges, motivation to quit smoking, and perceived taste of the cigarettes. Secondary outcomes measured post-intervention only will be experience of smoking from the cigarette pack, overall experience of smoking, attributes of the cigarette pack, perceptions of the on-packet health warnings, behavior changes, views on plain packaging, and the rewarding value of smoking. Sex differences will be explored for all analyses. -

Envelopes and Paper Sizes Envelopes

Envelopes and Paper Sizes Envelopes #10 Envelope - 4.125 x 9.5 inches. Standard envelope for a folded letter size paper to fit. #10 Window Envelope - Standard envelope for a folded letter size paper to fit with front window to allow a mailing address to show. 9 x 12 - Fits an unfolded letter size paper. 10 x 13 - Fits letter size paper or a 9 x 12 folder. Both envelopes are brown in color and open at the short end. Paper Sizes 8.5 x 11 Letter - Smallest page size we print on. If we are printing smaller items, they are printed in multiples on a larger sheet. 8.5 x 11 Legal - Slightly longer than a letter paper. Used commonly for exams and legal documents. 11 x 17 Tabloid - Equivalent of two 8.5 x 11 letter paper side by side. Used commonly for posters and 4 page folded documents. Some posters are not printed on this size since they require an image edge to edge (*bleed). 12 x 18 - One inch larger on both sides than 11x17. This is the paper that some posters are printed on and then trimmed to size to allow for bleed. 14 x 20 - We can print this size paper on our high volume printer. It is not a standard size paper, but allows for us to print at a slightly larger size. Larger than 14 x 20 would be printed on our large format printer. Anything larger than a 12 x 18 page cannot be printed by our front desk staff and needs to go to our designer so it can be printed on the appropriate device. -

PREFERRED PACKAGING: Accelerating Environmental Leadership in the Overnight Shipping Industry

PREFERRED PACKAGING: Accelerating Environmental Leadership in the Overnight Shipping Industry A Report by The Alliance for Environmental Innovation A Project of the Environmental Defense Fund and The Pew Charitable Trusts The Alliance for Environmental Innovation The Alliance for Environmental Innovation (the Alliance) is a joint initiative of the Environmental Defense Fund (EDF) and The Pew Charitable Trusts. The Alliance works cooperatively with private businesses to reduce waste and build environmental considerations into business decisions. By bringing the expertise and perspective of environmental scientists and economists together with the business skills of major corporations, the Alliance creates solutions that make environmental and business sense. Author This report was written by Elizabeth Sturcken. Ralph Earle and Richard Denison provided guidance and editorial review. Acknowledgments Funding for this report was provided by The Pew Charitable Trusts, the Environmental Protection Agency’s WasteWi$e Program and Office of Pollution Prevention, and the Emily Hall Tremaine Foundation. Disclaimer This report was prepared by the Alliance for Environmental Innovation to describe the packaging practices of the overnight shipping industry and identify opportunities for environmental improvement. Copyright of this report is held by the Alliance for Environmental Innovation. Any use of this report for marketing, advertising, promotional or sales purposes, is expressly prohibited. The contents of this report in no way imply endorsement of any company, product or service. Trademarks, trade names and package designs are the property of their respective owners. Ó Copyright The Alliance for Environmental Innovation The Alliance for Environmental Innovation is the product of a unique partnership between two institutions that are committed to finding cost-effective, practical ways to help American businesses improve their environmental performance. -

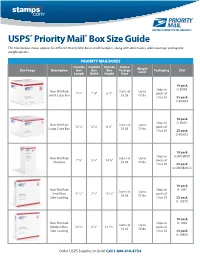

USPS Priority Mail Box Size Guide

USPS® Priority Mail® Box Size Guide The table below shows options for different Priority Mail Boxes and Envelopes, along with dimensions, online postage pricing and weight options. PRIORITY MAIL BOXES Outside Outside Outside Online Box Image Description Box Box Box Postage Weight Packaging SKU Length Width Height Price Limit 10 pack Ships in O-BOX4 Non-Flat Rate Starts at Up to 7 1/4" 7 1/4" 6 1/2" packs of Small Cube Box $5.05 70 lbs. 10 or 25 25 pack O-BOX4X 10 pack Ships in O-BOX7 Non-Flat Rate Starts at Up to 12 1/4" 12 1/4" 8 1/2" packs of Large Cube Box $5.05 70 lbs. 10 or 25 25 pack O-BOX7X 10 pack Ships in 0-SHOEBOX Non-Flat Rate Starts at Up to 7 5/8" 5 1/4" 14 5/8" packs of Shoebox $5.05 70 lbs. 10 or 25 25 pack 0-SHOEBOX-X 10 pack Non-Flat Rate Ships in O-1097 Starts at Up to Small Box, 11 5/8" 2 1/2" 13 7/16" packs of $5.05 70 lbs. Side-Loading 10 or 25 25 pack O-1097X 10 pack Non-Flat Rate Ships in O-1092 Starts at Up to Medium Box, 12 1/4" 2 7/8" 13 11/16" packs of $5.05 70 lbs. Side-Loading 10 or 25 25 pack O-1092X Order USPS Supplies in Bulk! Call 1-800-610-8734. 10 pack Non-Flat Rate Ships in O-1095X Starts at Up to Small Box, 12 7/16" 3 1/8" 15 5/8" packs of $5.05 70 lbs. -

Forensic Evidence Collection

Forensic Evidence Collection STEP 1-FOREIGN MATERIAL • Inside this bag is a paper “sheet”. Open bag and remove paper “sheet”. Place a hospital sheet on the floor of the exam room. Place the paper “sheet” on top of the hospital sheet. Have the patient undress on the paper “sheet”. This will collect any foreign material that can fall from the body in the process of undressing. Have paper bags available for the patient to deposit their clothes as they undress. If no paper bags are available, have a sheet/towel placed on the floor or on a stand so the patient can deposit clothing. Instruct the patient to place the clothing in such a manner as the clothing does not touch so as not to cross contaminate. Once the patient has undressed, have the patient don a gown and assist the patient to the exam bed/table. When collecting the paper “sheet”, fold the “sheet” in a bindle fold/druggist fold. This a fold where the edges fold upon themselves so as to keep any foreign material securely in the paper. Place the folded paper inside the “Step 1-Foreign Material” Collection bag. Seal the bag with evidence tape. Sign/date the evidence tape. Complete the form on the outside of the bag. Place step 1 collection in the “Sexual Assault Evidence Collection Kit” Envelope. • If the patient has changed clothes several times, had several bathes, or there is another reason as to why the patient would not have foreign material upon their body, then this step can be skipped. -

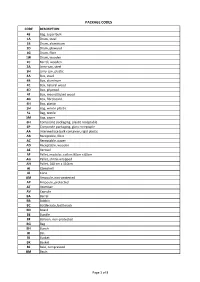

Package Codes

PACKAGE CODES CODE DESCRIPTION 43 Bag, super bulk 1A Drum, steel 1B Drum, aluminium 1D Drum, plywood 1G Drum, fibre 1W Drum, wooden 2C Barrel, wooden 3A Jerry-can, steel 3H Jerry-can, plastic 4A Box, steel 4B Box, aluminum 4C Box, natural wood 4D Box, plywood 4F Box, reconstituted wood 4G Box, fibreboard 4H Box, plastic 5H Bag, woven plastic 5L Bag, textile 5M Bag, paper 6H ComposIte packaging, plastic receptable 6P Composite packaging, glass receptaple AA Intermediate bulk container, rigid plastic AB Receptable, fibre AC Receptable, paper AD Receptable, wooden AE Aerosol AF Pallet, modular, collars 80cm x 60cm AG Pallet, shrink-wrapped AH Pallet, 100 cm x 110cm AI Clamshell AJ Cone AM Ampoule, non-protected AP Ampoule, protected AT Atomiser AV Capsule BA Barrel BB Bobbin BC Bottlecrate, bottlerack BD Board BE Bundle BF Balloon, non-protected BG Bag BH Bunch BI Bin BJ Bucket BK Basket BL Bale, compressed BM Basin Page 1 of 8 PACKAGE CODES CODE DESCRIPTION BN Bale, non-compressed BO Bottle, non-protected, cylindrical BP Balloon, protected BQ Bottle, protected cylindrical BR Bar BS Bottle, non-protected, bulbous BT Bolt BU Butt BV Bottle, protected bulbous BW Box, for liquids BX Box BY Board, in bundle/bunch/truss, BZ Bars, in bundle/bunch/truss CA Can, rectangular CB Beer crate CC Churn CD Can, with handle and spout CE Creel CF Coffer CG Cage CH Chest CI Canister CJ Coffin CK Cask CL Coil CM Collis CN Container not otherwise specified as transport equipment CO Carboy, non-protected CP Carboy, protected CQ Cartdidge CR Crate CS Case CT -

Regional Supply Service Center Catalog

REGIONAL SUPPLY SERVICE CENTER CATALOG ALASKA NATIVE TRIBAL HEALTH CONSORTIUM REGIONAL SUPPLY SERVICE CENTER 6130 TUTTLE PLACE #2 ANCHORAGE, ALASKA 99507 TELEPHONE: 907-729-2980 FACSIMILE: 907-729-2995 Regional Supply Service Center The Regional Supply Service Center is a 23,000 square foot warehouse that is part of the dynamic Alaska Native Tribal Health Consortium. We are proud to serve the extended campus and Alaska Tribal Health System. Including seven hospitals, 12 health centers and 200+ health aide clinics. Our purchases are made with over two hundred vendors nation- wide, utilizing on-line computer ordering with major suppliers. Approximately 3,600 purchase orders are processed annually. Our Services: Pharmaceutical, medical, dental, office and other supplies stocked for your convenience. Employees with decades of experience to better help your needs. Multiple choices for ordering. Our Mission: Here at the Regional Supply Service Center (RSSC) our mission is to design, implement and manage a quality, timely, reliable and cost effective supply system. This system provides equal services to all tribal health care facilities in Alaska; to ensure that health care providers have the pharmaceuticals, medical supplies and other material required to provide a quality health care service. With the Alaska Native Tribal Health Consortium, our mission is to provide the highest quality health services in partnership with our people and the Alaska Tribal Health System. Our Vision: Alaska Natives are the healthiest people in the world. Our Values: Achieving excellence. Native self-determination. Treat with respect and integrity. Health and wellness. Compassion. PRICE POLICY: We reserve the right to make price adjustments in response to manufacturers’ price increases or extraordinary circumstances. -

A Guide to the 8 Most Popular Folds 4 3 4 3 4 3 4 3 (Bi-Fold Or Single Fold) 1

4 5 4 5 4 5 4 5 3 6 3 6 3 6 6 5. Quarter Fold (French Fold) 3 5.. Quarrtterr Folld ((Frrench Folld)) -- Sheett off paperr iis f-o Sldedhee tve orf tpapeical, trhen is 2 7 ffollded verrttiical,l, tthen 2 7 ffollded agaiin 1 8 5..hof oQldedruaizonrr ttagaetarr llFoyin. l ld ((Frrench Folld)) 1 8 5.ho Qrriuaizonrtettarll llFoy.. ld (French Fold) -- S-- heeUsestt o:: fLef papetttterrsrr , ,i i sG rreetiting carrds,, Fllyerrs//Brrochurres f-o S-l dedheeUses tve o: rfLe tpapeicattel,r strhen ,i sG r eeting cards, Flyers/Brochures 5. Qffuao--ll ded r2t e ffor lveFoldsrrl,,tdt iittca ha(Fl,l,trt enctcthenrreah t teFo 1l d tto) 8 arreas fforr prriintt.. 5.. Quafo-l dedrr2tte frro Folagavedslrl,dt it nca ha((F l,rrtenc tchenreah tFoe 1lld t))o 8 areas for print. 5. Qff oualldedrte raga Foiilnd (French Fold) -- 5S..hee Qhof ouatltded r oirzonrftft e pape rraga tFoallylilrrdn . i i s((F rrench Folld)) - 5S.hee Qho uatrr iiozonrft epapert taFollllylrd.. i s(F rench Fold) fo-l dedShee-ho U versestizon ortfi ca:pape tLeal,ll yttthen.er riss, Greeting cards, Flyers/Brochures ffo--l l dedShee-- U vesestt orrttfifi ca: :pape Lel,l, tttttthenerr r risis,, Grreetiting carrds,, Fllyerrs//Brrochurres fofoldedlded- 2U 6aga .sesfve oQldsrinuat:i ca Le, rtthal,tte ert hentrPocke sc,r eaG rteeet Fo1ti ngtold 8ca( Rarordseasll ,Fo F floydre) rpsr/iBntr.o chures ffoffolldedllded-- 2 6 aga ..fvef oQlldsririnuattiica ,, rrttthatl,l,e rtrt hent tPocke crrea ttett Fo1 ttolld 8 (( R aorreasllll Fo ffllodrr)) prriintt. -

Cigarette Pack Size and Consumption: an Adaptive Randomised Controlled Trial Ilse Lee1, Anna K

Lee et al. BMC Public Health (2021) 21:1420 https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-021-11413-4 RESEARCH ARTICLE Open Access Cigarette pack size and consumption: an adaptive randomised controlled trial Ilse Lee1, Anna K. M. Blackwell2, Michelle Scollo3, Katie De-loyde2, Richard W. Morris4, Mark A. Pilling1, Gareth J. Hollands1, Melanie Wakefield3, Marcus R. Munafò2 and Theresa M. Marteau1* Abstract Background: Observational evidence suggests that cigarette pack size – the number of cigarettes in a single pack – is associated with consumption but experimental evidence of a causal relationship is lacking. The tobacco industry is introducing increasingly large packs, in the absence of maximum cigarette pack size regulation. In Australia, the minimum pack size is 20 but packs of up to 50 cigarettes are available. We aimed to estimate the impact on smoking of reducing cigarette pack sizes from ≥25 to 20 cigarettes per pack. Method: A two-stage adaptive parallel group RCT in which Australian smokers who usually purchase packs containing ≥25 cigarettes were randomised to use only packs containing either 20 (intervention) or their usual packs (control) for four weeks. The primary outcome, the average number of cigarettes smoked per day, was measured through collecting all finished cigarette packs, labelled with the number of cigarettes participants smoked. An interim sample size re-estimation was used to evaluate the possibility of detecting a meaningful difference in the primary outcome. Results: The interim analysis, conducted when 124 participants had been randomised, suggested 1122 additional participants needed to be randomised for sufficient power to detect a meaningful effect. This exceeded pre- specified criteria for feasible recruitment, and data collection was terminated accordingly.