Cigarette Pack Size and Consumption: an Adaptive Randomised Controlled Trial Ilse Lee1, Anna K

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Tobacco Industry Tactics: Packaging and Labelling

WHO-EM/TFI/201/E Tobacco industry tactics: packaging and labelling Tobacco packs are key to marketing and advertising. The tobacco industry challenges large, graphic warnings and pack size/colour restrictions using intellectual property and “slippery slope” arguments. Through litigation, or threat of litigation, the industry seeks to delay implementation of packaging and labelling restrictions. Donations, political contributions and so- called corporate social responsibility (CSR) activities can result in pro-industry arguments gaining political support. Introduction Tobacco packaging is a potent marketing tool. Pack design and colour are used to manipulate people’s perception of the level of harm and increase the products’ appeal, especially among the young, including young women (1–4). For the public health community, packaging is an important medium for communicating health messages (5). Studies from all over the world have concluded that large graphic warnings are associated with reduced tobacco consumption and smoking prevalence, and with increased knowledge of health risks and efforts to quit(6) . Therefore, Article 11 of the World Health Organization Framework Convention on Tobacco Control (WHO FCTC) mandates the adoption and implementation of health warnings on tobacco product packaging and labelling. Article 11 of the WHO FCTC focuses on two key aspects: an effective warning label; and restrictions on misleading or deceptive packaging/labelling elements, including descriptors (light, mild, low tar), emissions yields, and other elements that detract from health warnings or convey that one product is safer than another. To undermine the effectiveness of packaging and labelling regulations, tobacco companies increasingly use pack colours to replace misleading descriptors and convey the perception of “reduced risk”, to diminish health concerns and reduce the impact of health warning labels (7). -

Single Sample Sequencing Data Sheet

Single sample sequencing service includes FREE - repeats for failed sequences (Flexi / Premium Run) - use of our Pick-up boxes at various locations Single sample sequencing - universal primers (Flexi / Premium Run) - LGC plasmid DNA standard (simply load and compare 2 μL (100 ng) of plasmid DNA standard to your plasmid preparation) - sample bags for secure sample shipment analytical quality • measur eme nt ac • Automated and standardised ABI 3730 XL cu ra sequencing run with a read length up to 1,100 nt c y (PHRED20 quality) • re g • Overnight turnaround if samples are delivered u la before 10 am t o r • Stored customer-specific primers are selectable y t during online ordering for 3 months e s t i • Return of aliquots of synthesised primers on request. n g • Expert advice and customer support on c h Tel: +49 (0)30 5304 2230 from 8 am to 6 pm e Monday to Friday m i c a l Online ordering system m e To place your order please visit our webpage and a s u log onto our online ordering system at r e https://shop.lgcgenomics.com m e n t • Register as a new user • b i • Choose your sequencing service, order labels, o a n manage your data and shipment order a l y s i s • Please prepare your samples according to the given • s t a n d a r d s • f o r e n s i c t e s t i n requirements and send your samples in a padded g envelope to us. -

The EMA Guide to Envelopes and Mailing

The EMA Guide to Envelopes & Mailing 1 Table of Contents I. History of the Envelope An Overview of Envelope Beginnings II. Introduction to the Envelope Envelope Construction and Types III. Standard Sizes and How They Originated The Beginning of Size Standardization IV. Envelope Construction, Seams and Flaps 1. Seam Construction 2. Glues and Flaps V. Selecting the Right Materials 1. Paper & Other Substrates 2. Window Film 3. Gums/Adhesives 4. Inks 5. Envelope Storage 6. Envelope Materials and the Environment 7. The Paper Industry and the Environment VI. Talking with an Envelope Manufacturer How to Get the Best Finished Product VII. Working with the Postal Service Finding the Information You Need VIII. Final Thoughts IX. Glossary of Terms 2 Forward – The EMA Guide to Envelopes & Mailing The envelope is only a folded piece of paper yet it is an important part of our national communications system. The power of the envelope is the power to touch someone else in a very personal way. The envelope has been used to convey important messages of national interest or just to say “hello.” It may contain a greeting card sent to a friend or relative, a bill or other important notice. The envelope never bothers you during the dinner hour nor does it shout at you in the middle of a television program. The envelope is a silent messenger – a very personal way to tell someone you care or get them interested in your product or service. Many people purchase envelopes over the counter and have never stopped to think about everything that goes into the production of an envelope. -

Food Packaging Technology

FOOD PACKAGING TECHNOLOGY Edited by RICHARD COLES Consultant in Food Packaging, London DEREK MCDOWELL Head of Supply and Packaging Division Loughry College, Northern Ireland and MARK J. KIRWAN Consultant in Packaging Technology London Blackwell Publishing © 2003 by Blackwell Publishing Ltd Trademark Notice: Product or corporate names may be trademarks or registered Editorial Offices: trademarks, and are used only for identification 9600 Garsington Road, Oxford OX4 2DQ and explanation, without intent to infringe. Tel: +44 (0) 1865 776868 108 Cowley Road, Oxford OX4 1JF, UK First published 2003 Tel: +44 (0) 1865 791100 Blackwell Munksgaard, 1 Rosenørns Allè, Library of Congress Cataloging in P.O. Box 227, DK-1502 Copenhagen V, Publication Data Denmark A catalog record for this title is available Tel: +45 77 33 33 33 from the Library of Congress Blackwell Publishing Asia Pty Ltd, 550 Swanston Street, Carlton South, British Library Cataloguing in Victoria 3053, Australia Publication Data Tel: +61 (0)3 9347 0300 A catalogue record for this title is available Blackwell Publishing, 10 rue Casimir from the British Library Delavigne, 75006 Paris, France ISBN 1–84127–221–3 Tel: +33 1 53 10 33 10 Originated as Sheffield Academic Press Published in the USA and Canada (only) by Set in 10.5/12pt Times CRC Press LLC by Integra Software Services Pvt Ltd, 2000 Corporate Blvd., N.W. Pondicherry, India Boca Raton, FL 33431, USA Printed and bound in Great Britain, Orders from the USA and Canada (only) to using acid-free paper by CRC Press LLC MPG Books Ltd, Bodmin, Cornwall USA and Canada only: For further information on ISBN 0–8493–9788–X Blackwell Publishing, visit our website: The right of the Author to be identified as the www.blackwellpublishing.com Author of this Work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. -

Plain-Packaging.Pdf

Plain Packaging Commercial expression, anti-smoking extremism and the risks of hyper-regulation Christopher Snowdon www.adamsmith.org Plain Packaging Commercial expression, anti-smoking extremism and the risks of hyper-regulation Christopher Snowdon The views expressed in this report are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect any views held by the publisher or copyright owner. They are published as a contribution to public debate. Copyright © Adam Smith Research Trust 2012 All rights reserved. Published in the UK by ASI (Research) Ltd. ISBN: 1-902737-84-9 Printed in England Contents Executive Summary 5 1 A short history of plain packaging 7 2 Advertising? 11 3 Scraping the barrel 13 4 Will it work? 18 5 Unintended consequences 23 6 Intellectual property 29 7 Who’s next? 31 8 Conclusion 36 Executive summary 1. The UK government is considering the policy of ‘plain packaging’ for tobacco products. If such a law is passed, all cigarettes, cigars and smokeless tobacco will be sold in generic packs without branding or trademarks. All packs will be the same size and colour (to be decided by the government) and the only permitted images will be large graphic warnings, such as photos of tumours and corpses. Consumers will be able to distinguish between products only by the brand name, which will appear in a small, standardised font. 2. As plain packaging has yet to be tried anywhere in the world, there is no solid evidence of its efficacy or unintended consequences. 3. Focus groups and opinion polls have repeatedly shown that the public does not believe that plain packaging will stop people smoking. -

Plain Packaging of Cigarettes and Smoking Behavior

Maynard et al. Trials 2014, 15:252 http://www.trialsjournal.com/content/15/1/252 TRIALS STUDY PROTOCOL Open Access Plain packaging of cigarettes and smoking behavior: study protocol for a randomized controlled study Olivia M Maynard1,2,3*, Ute Leonards3, Angela S Attwood1,2,3, Linda Bauld2,4, Lee Hogarth5 and Marcus R Munafò1,2,3 Abstract Background: Previous research on the effects of plain packaging has largely relied on self-report measures. Here we describe the protocol of a randomized controlled trial investigating the effect of the plain packaging of cigarettes on smoking behavior in a real-world setting. Methods/Design: In a parallel group randomization design, 128 daily cigarette smokers (50% male, 50% female) will attend an initial screening session and be assigned plain or branded packs of cigarettes to smoke for a full day. Plain packs will be those currently used in Australia where plain packaging has been introduced, while branded packs will be those currently used in the United Kingdom. Our primary study outcomes will be smoking behavior (self-reported number of cigarettes smoked and volume of smoke inhaled per cigarette as measured using a smoking topography device). Secondary outcomes measured pre- and post-intervention will be smoking urges, motivation to quit smoking, and perceived taste of the cigarettes. Secondary outcomes measured post-intervention only will be experience of smoking from the cigarette pack, overall experience of smoking, attributes of the cigarette pack, perceptions of the on-packet health warnings, behavior changes, views on plain packaging, and the rewarding value of smoking. Sex differences will be explored for all analyses. -

Lao Peoples Democratic Republic Peace Independence Democracy Unity Prosperity

Unofficial Translation [LPDR Seal] Lao Peoples Democratic Republic Peace Independence Democracy Unity Prosperity ---------------------------------------- Ministry of Public Health No. 992 / MPH Vientiane, Date: 24 APR 2014 AGREEMENT Governing Health Warning Notices to be Printed on Cigarette Packs and Cartons - Reference: The Tobacco Control Act, No. 07 / N.A. [National Assembly], dated 26 November 2009; - Reference: Decree on the Fund for Tobacco Control, No. 155 / L.B. [expansion unknown], dated 21 April 2013; - Reference: Decree on Printing of Health Warnings on Packaging Materials for Tobacco Products, No. 370 / PMO [Prime Minister’s Office], dated 23 August 2010; - Reference: Prime Minister’s Decree No. 178 / P.M. [Prime Minister], dated 5 April 2012, Subject: Establishment and Operations of the Ministry of Public Health; and - Reference: Research and Proposals by the Office of the Fund for Tobacco Control. The Minister of Public Health Agrees That: Part I General Provisions Article 1. Purpose 1. Purpose • To improve the principles, regulations, and measures for control and inspection of the printing of health warning labels on packs and cartons of cigarettes, since some of the label content prescribed previously in the Decree on Health Warnings to Be Printed on Packaging Unofficial Translation Materials for Tobacco Products, No. 370 / PMO, dated 23 August 2010, is not adequate or properly aligned with international agreements on tobacco control. • To keep pace with medical science data relating to smoking and inhalation of tobacco smoke, particularly with regard to the diseases that are caused by tobacco and tobacco smoke. 2. Level of Expectation Every pack and carton of cigarettes produced domestically or imported from abroad must bear printed health warnings and the primary chemical components of tobacco products that are known health hazards. -

Camel Crush Classic&Quo

Programmatic Environmental Assessment for Marketing Orders for R.J. Reynolds Tobacco Company's "Camel Crush Classic" and "Camel Crush Blue" Prepared by Center for Tobacco Products U.S. Food and Drug Administration June 28, 2018 1 Table of Contents 1. Name of Applicant...............................................................................................................................3 2. Address ................................................................................................................................................3 3. Manufacturer ......................................................................................................................................3 4. Description of Proposed Actions .........................................................................................................3 4.1 Requested Actions ..............................................................................................................................3 4.2 Need for Actions..................................................................................................................................3 4.3 Identification of the New Tobacco Products that are the Subject of the Proposed Actions .............. 3 4.3.1 Type of Tobacco Products ...................................................................................................................3 4.3.2 Product Names and the Submission Tracking Numbers (STNs) .......................................................... 4 4.3.3 Description of the Product -

Guide to the Virgil Johnson Collection of Cigarette Packages

Guide to the Virgil Johnson Collection of Cigarette Packages NMAH.AC.0645 Mimi Minnick July 1998 Archives Center, National Museum of American History P.O. Box 37012 Suite 1100, MRC 601 Washington, D.C. 20013-7012 [email protected] http://americanhistory.si.edu/archives Table of Contents Collection Overview ........................................................................................................ 1 Administrative Information .............................................................................................. 1 Biographical / Historical.................................................................................................... 2 Arrangement..................................................................................................................... 3 Scope and Contents........................................................................................................ 2 Names and Subjects ...................................................................................................... 3 Container Listing ............................................................................................................. 4 Series 1: Cigarette Packages, circa 1890-1997....................................................... 4 Series 2: Articles and Other Publications About Tobacco and Tobacco Collecting, 1927-1994................................................................................................................. 9 Series 3: Books About Tobacco and Tobacco Collecting...................................... -

Envelopes and Paper Sizes Envelopes

Envelopes and Paper Sizes Envelopes #10 Envelope - 4.125 x 9.5 inches. Standard envelope for a folded letter size paper to fit. #10 Window Envelope - Standard envelope for a folded letter size paper to fit with front window to allow a mailing address to show. 9 x 12 - Fits an unfolded letter size paper. 10 x 13 - Fits letter size paper or a 9 x 12 folder. Both envelopes are brown in color and open at the short end. Paper Sizes 8.5 x 11 Letter - Smallest page size we print on. If we are printing smaller items, they are printed in multiples on a larger sheet. 8.5 x 11 Legal - Slightly longer than a letter paper. Used commonly for exams and legal documents. 11 x 17 Tabloid - Equivalent of two 8.5 x 11 letter paper side by side. Used commonly for posters and 4 page folded documents. Some posters are not printed on this size since they require an image edge to edge (*bleed). 12 x 18 - One inch larger on both sides than 11x17. This is the paper that some posters are printed on and then trimmed to size to allow for bleed. 14 x 20 - We can print this size paper on our high volume printer. It is not a standard size paper, but allows for us to print at a slightly larger size. Larger than 14 x 20 would be printed on our large format printer. Anything larger than a 12 x 18 page cannot be printed by our front desk staff and needs to go to our designer so it can be printed on the appropriate device. -

PREFERRED PACKAGING: Accelerating Environmental Leadership in the Overnight Shipping Industry

PREFERRED PACKAGING: Accelerating Environmental Leadership in the Overnight Shipping Industry A Report by The Alliance for Environmental Innovation A Project of the Environmental Defense Fund and The Pew Charitable Trusts The Alliance for Environmental Innovation The Alliance for Environmental Innovation (the Alliance) is a joint initiative of the Environmental Defense Fund (EDF) and The Pew Charitable Trusts. The Alliance works cooperatively with private businesses to reduce waste and build environmental considerations into business decisions. By bringing the expertise and perspective of environmental scientists and economists together with the business skills of major corporations, the Alliance creates solutions that make environmental and business sense. Author This report was written by Elizabeth Sturcken. Ralph Earle and Richard Denison provided guidance and editorial review. Acknowledgments Funding for this report was provided by The Pew Charitable Trusts, the Environmental Protection Agency’s WasteWi$e Program and Office of Pollution Prevention, and the Emily Hall Tremaine Foundation. Disclaimer This report was prepared by the Alliance for Environmental Innovation to describe the packaging practices of the overnight shipping industry and identify opportunities for environmental improvement. Copyright of this report is held by the Alliance for Environmental Innovation. Any use of this report for marketing, advertising, promotional or sales purposes, is expressly prohibited. The contents of this report in no way imply endorsement of any company, product or service. Trademarks, trade names and package designs are the property of their respective owners. Ó Copyright The Alliance for Environmental Innovation The Alliance for Environmental Innovation is the product of a unique partnership between two institutions that are committed to finding cost-effective, practical ways to help American businesses improve their environmental performance. -

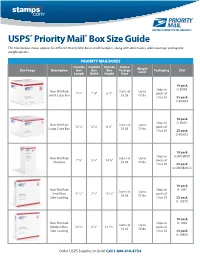

USPS Priority Mail Box Size Guide

USPS® Priority Mail® Box Size Guide The table below shows options for different Priority Mail Boxes and Envelopes, along with dimensions, online postage pricing and weight options. PRIORITY MAIL BOXES Outside Outside Outside Online Box Image Description Box Box Box Postage Weight Packaging SKU Length Width Height Price Limit 10 pack Ships in O-BOX4 Non-Flat Rate Starts at Up to 7 1/4" 7 1/4" 6 1/2" packs of Small Cube Box $5.05 70 lbs. 10 or 25 25 pack O-BOX4X 10 pack Ships in O-BOX7 Non-Flat Rate Starts at Up to 12 1/4" 12 1/4" 8 1/2" packs of Large Cube Box $5.05 70 lbs. 10 or 25 25 pack O-BOX7X 10 pack Ships in 0-SHOEBOX Non-Flat Rate Starts at Up to 7 5/8" 5 1/4" 14 5/8" packs of Shoebox $5.05 70 lbs. 10 or 25 25 pack 0-SHOEBOX-X 10 pack Non-Flat Rate Ships in O-1097 Starts at Up to Small Box, 11 5/8" 2 1/2" 13 7/16" packs of $5.05 70 lbs. Side-Loading 10 or 25 25 pack O-1097X 10 pack Non-Flat Rate Ships in O-1092 Starts at Up to Medium Box, 12 1/4" 2 7/8" 13 11/16" packs of $5.05 70 lbs. Side-Loading 10 or 25 25 pack O-1092X Order USPS Supplies in Bulk! Call 1-800-610-8734. 10 pack Non-Flat Rate Ships in O-1095X Starts at Up to Small Box, 12 7/16" 3 1/8" 15 5/8" packs of $5.05 70 lbs.