Ischemic Colitis Complicating Major Vascular Surgery Scott R

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Coding for Angioplasty & Stent Procedures

Coding for Angioplasty & Stent Procedures July 2020 Jennifer Bash, RHIA, CIRCC, RCCIR, CPC, RCC Director of Coding Education Agenda • Introduction • Definitions • General Coding Guidelines • Presenting Problems/Medical Necessity for Angioplasty & Stent • General Angioplasty & Stent Procedures • Cervicocerebral Procedures • Lower Extremity Procedures Disclaimer The information presented is based on the experience and interpretation of the presenters. Though all of the information has been carefully researched and checked for accuracy and completeness, ADVOCATE does not accept any responsibility or liability with regard to errors, omissions, misuse or misinterpretation. CPT codes are trademark and copyright of the American Medical Association. Resources •AMA •CMS • ACR/SIR • ZHealth Publishing Angioplasty & Stent Procedures Angioplasty Angioplasty, also known as balloon angioplasty and percutaneous transluminal angioplasty, is a minimally invasive endovascular procedure used to widen narrowed or obstructed arteries or veins, typically to treat arterial atherosclerosis. Vascular Stent A stent is a tiny tube placed into the artery or vein used to treat vessel narrowing or blockage. Most stents are made of a metal or plastic mesh-like material. General Angioplasty & Stent Coding Guidelines • Angioplasty is not separately billable when done with a stent • Pre-Dilatation • PTA converted to Stent • Prophylaxis • EXCEPTION-Complication extending to a different vessel • Coded per vessel • Codes include RS&I • Territories • Hierarchy General Angioplasty -

Twisted Bowels: Intestinal Obstruction Blake Briggs, MD Mechanical

Twisted Bowels: Intestinal obstruction Blake Briggs, MD Objectives: define bowel obstructions and their types, pathophysiology, causes, presenting signs/symptoms, diagnosis, and treatment options, as well as the complications associated with them. Bowel Obstruction: the prevention of the normal digestive process as well as intestinal motility. 2 overarching categories: Mechanical obstruction: More common. physical blockage of the GI tract. Can be complete or incomplete. Complete obstruction typically is more severe and more likely requires surgical intervention. Functional obstruction: diffuse loss of intestinal motility and digestion throughout the intestine (e.g. failure of peristalsis). 2 possible locations: Small bowel: more common Large bowel All bowel obstructions have the potential risk of progressing to complete obstruction Mechanical obstruction Pathophysiology Mechanical blockage of flow à dilation of bowel proximal to obstruction à distal bowel is flattened/compressed à Bacteria and swallowed air add to the proximal dilation à loss of intestinal absorptive capacity and progressive loss of fluid across intestinal wall à dehydration and increasing electrolyte abnormalities à emesis with excessive loss of Na, K, H, and Cl à further dilation leads to compression of blood supply à intestinal segment ischemia and resultant necrosis. Signs/Symptoms: The goal of the physical exam in this case is to rule out signs of peritonitis (e.g. ruptured bowel). Colicky abdominal pain Bloating and distention: distention is worse in distal bowel obstruction. Hyperresonance on percussion. Nausea and vomiting: N/V is worse in proximal obstruction. Excessive emesis leads to hyponatremic, hypochloremic metabolic alkalosis with hypokalemia. Dehydration from emesis and fluid shifts results in dry mucus membranes and oliguria Obstipation: severe constipation or complete lack of bowel movements. -

Coronary Angiogram, Angioplasty and Stent Placement

Page 1 of 6 Coronary Angiogram, Angioplasty and Stent Placement A Patient’s Guide Page 2 of 6 What is coronary artery disease? What is angioplasty and a stent? Coronary artery disease means that you have a If your doctor finds a blocked artery during your narrowed or blocked artery. It is caused by the angiogram, you may need an angioplasty (AN-jee- buildup of plaque (fatty material) inside the artery o-plas-tee). This is a procedure that uses a small over many years. This buildup can stop blood from inflated balloon to open a blocked artery. It can be getting to the heart, causing a heart attack (the death done during your angiogram test. of heart muscle cells). The heart can then lose some of its ability to pump blood through the body. Your doctor may also place a stent at this time. A stent is a small mesh tube that is placed into an Coronary artery disease is the most common type of artery to help keep it open. Some stents are coated heart disease. It is also the leading cause of death for with medicine, some are not. Your doctor will both men and women in the United States. For this choose the stent that is right for you. reason, it is important to treat a blocked artery. Angioplasty and stent Anatomy of the Heart 1. Stent with 2. Balloon inflated 3. Balloon balloon inserted to expand stent. removed from into narrowed or expanded stent. What is a coronary angiogram? blocked artery. A coronary angiogram (AN-jee-o-gram) is a test that uses contrast dye and X-rays to look at the blood vessels of the heart. -

Case Report Long-Term Results of Vascular Stent Placements for Portal Vein Stenosis Following Liver Transplantation

Int J Clin Exp Med 2017;10(3):5514-5520 www.ijcem.com /ISSN:1940-5901/IJCEM0042813 Case Report Long-term results of vascular stent placements for portal vein stenosis following liver transplantation Yue-Lin Zhang1,2, Chun-Hui Nie1,2, Guan-Hui Zhou1,2, Tan-Yang Zhou1,2, Tong-Yin Zhu1,2, Jing Ai3, Bao-Quan Wang1,2, Sheng-Qun Chen1,2, Zi-Niu Yu1,2, Wei-Lin Wang1,2, Shu-Sen Zheng1,2, Jun-Hui Sun1,2 1Department of Hepatobiliary and Pancreatic Interventional Center, The First Affiliated Hospital, School of Medi- cine, Zhejiang University, Hangzhou 310003, Zhejiang Province, China; 2Key Laboratory of Combined Multi-organ Transplantation, Ministry of Public Health, Hangzhou 310003, Zhejiang Province, China; 3Department of Oph- thalmology, The Second Affiliated Hospital, School of Medicine, Zhejiang University, Hangzhou 310009, Zhejiang Province, China Received October 25, 2016; Accepted January 4, 2017; Epub March 15, 2017; Published March 30, 2017 Abstract: Portal vein stenosis (PVS) is a serious complication after liver transplantation (LT) and can cause in- creased morbidity, graft loss, and patient death. The aim of this study was to evaluate the long-term treatment ef- fect of vascular stents in the management of PVS after LT. In the present study, follow-up data on 16 patients who received vascular stents for PVS after LT between July 2011 and May 2015 were analyzed. Of these, five patients had portal hypertension-related signs and symptoms. All procedures were performed with direct puncture of the intrahepatic portal vein and with subsequent stent placement. Embolization was required for significant collateral circulation. -

Total Arch Replacement for Aortic Arch Aneurysm with Coexisting Middle Aortic Syndrome

CASE REPORT – OPEN ACCESS International Journal of Surgery Case Reports 54 (2019) 79–82 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect International Journal of Surgery Case Reports journa l homepage: www.casereports.com Total arch replacement for aortic arch aneurysm with coexisting middle aortic syndrome ∗ Zaiqiang Yu, Masahito Minakawa , Norihiro Kondo, Kazuyuki Daitoku, Ikuo Fukuda Department of Thoracic and Cardiovascular Surgery, Hirosaki University Graduate School of Medicine, Aomori, Japan a r a t i b s c t l e i n f o r a c t Article history: Introduction: Middle aortic syndrome (MAS) combined with thoracic aortic aneurysm (TAA) is a rare vas- Received 20 September 2018 cular disease. One stage open surgery to treat this condition, becomes a challenge for our cardiovascular Received in revised form surgery. 15 November 2018 Presentation of case: A 69-year-old man presented with a saccular type aortic arch aneurysm, shaggy Accepted 19 November 2018 aorta and severe atherosclerotic stenosis of the thoracoabdominal aorta with middle aortic syndrome and Available online 24 November 2018 aberrant right subclavian artery, renovascular hypertension, renal dysfunction, and intermittent claudi- cation of both legs. Total arch replacement procedure was performed under a cardiopulmonary bypass Keywords: using aortic inflow from the right axillary artery and a femoro-femoral crossover bypass graft to avoid Aortic arch aneurysm malperfusion of the lower body. Before weaning from the cardiopulmonary bypass, we established an Middle aortic syndrome Axillary-femoral artery bypass extra-anatomical bypass from the ascending aortic graft to the femoro-femoral crossover bypass graft. Case report 3D-CT showed patency of bypass graft without any sign of stenosis postoperative. -

Jejunoileal Diverticulitis: Big Trouble in Small Bowel

Jejunoileal Diverticulitis: Big Trouble in Small Bowel MICHAEL CARUSO DO, HAO LO MD EMERGENCY RADIOLOGY, UMASS MEMORIAL MEDICAL CENTER, WORCESTER, MA LEARNING OBJECTIVES: After excluding Meckel’s diverticulum, less than 30% of reported diverticula occurred in the CASE 1 1. Be aware of the relatively rare diagnoses of jejunoileal jejunum and ileum. HISTORY: 52 year old female with left upper quadrant pain. diverticulosis (non-Meckelian) and diverticulitis. Duodenal diverticula are approximately five times more common than jejunoileal diverticula. FINDINGS: 2.2 cm diverticulum extending from the distal ileum with adjacent induration of the mesenteric fat, consistent with an ileal diverticulitis. 2. Learn the epidemiology, pathophysiology, imaging findings and differential diagnosis of jejunoileal diverticulitis. Diverticulaare sac-like protrusions of the bowel wall, which may be composed of mucosa and submucosa only (pseudodiverticula) or of all CT Findings (2) layers of the bowel wall (true . Usually presents as a focal area of bowel wall thickening most prominent on the mesenteric side of AXIAL AXIAL CORONAL diverticula) the bowel with adjacent inflammation and/or abscess formation . Diverticulitis is the result of When abscess is present, CT findings may include relatively smooth margins, areas of low CASE 2 obstruction of the neck of the attenuation within the mass, rim enhancement after IV contrast administration, gas within the HISTORY: 62 year old female with epigastric and left upper quadrant pain. diverticulum, with subsequent mass, displacement of the surrounding structures, and edema of thickening of the surrounding fat inflammation, perforation and or fascial planes FINDINGS: 4.7 cm diameter out pouching seen arising from the proximal small bowel and associated with adjacent inflammatory stranding. -

Ischaemic Colitis: Practical Challenges and Evidence-Based Recommendations For

Ischaemic Colitis: Practical Challenges and Evidence-Based Recommendations for Management Alexander Hung1*, Tom Calderbank1*, Mark A Samaan1, Andrew A Plumb2, George Webster1 Author affiliations 1Department of Gastroenterology, University College London Hospitals, London, UK 2Department of Radiology, University College London Hospitals, London, UK *Authors contributed equally Correspondence to Mark A Samaan Department of Gastroenterology University College London Hospitals 250 Euston Road London NW1 2PG [email protected] Running title Ischaemic Colitis Management Word count 3212 Key Words Ischaemic colitis, colonic ischaemia ABSTRACT Ischaemic colitis (IC) is a common condition with rising incidence and, in severe cases, a high mortality rate. Its presentation, severity and disease behaviour can vary widely and there exists significant heterogeneity in treatment strategies and resultant outcomes. In this article we explore practical challenges in the management of IC and where available, make evidence-based recommendations for its management based on a comprehensive review of available literature. An optimal approach to initial management requires early recognition of the diagnosis followed by prompt and appropriate investigation. Ideally, this should involve the input of both gastroenterology and surgery. CT with intravenous and oral contrast is the imaging modality of choice. It can support a clinical diagnosis, define the severity and distribution of ischaemia and has prognostic value. In all but fulminant cases, this should be followed (within 48 hours) by lower GI endoscopy to reach the distal-most extent of the disease, providing endoscopic (and histological) confirmation. The mainstay of medical management is conservative/supportive treatment, with bowel rest, fluid resuscitation and antibiotics. Specific laboratory, radiological and endoscopic features are recognised to correlate with more severe disease, higher rates of surgical intervention and ultimately worse outcomes. -

Coping with the Problems of Diagnosis of Acute Colitis

Diagnostic and Interventional Imaging (2013) 94, 793—804 . CONTINUING EDUCATION PROGRAM: FOCUS . Coping with the problems of diagnosis of acute colitis a,∗,c b a E. Delabrousse , F. Ferreira , N. Badet , a b M. Martin , M. Zins a Urinogenital and Digestive Imaging Department, hôpital Jean-Minjoz, CHRU de Besanc¸on, 3, boulevard Fleming, 25030 Besanc¸on, France b Radiology Department, hôpital Saint-Joseph, 184, rue Raymond-Losserand, 75014 Paris, France c EA 4662, Nanomedicine Laboratory, Imagery and Therapeutics, University of Franche-Comté, Besanc¸on, France KEYWORDS Abstract Acute colitis is an acute condition of the colon. For the radiologist, it is mainly Colitis; diagnosed during differential diagnosis of acute abdominal conditions. There are many causes Ischaemia; of colitis and the degree of its severity varies. A CT scan is the best imaging examination for IBD; diagnosing it and also for analysing and characterising colitis. The topography, type of lesion Pseudomembranous; and associated factors can often suggest a precise diagnosis but it is nevertheless essential to Neutropenia integrate these findings into the clinical context and take laboratory values into account. The use of endoscopy is still the rule where a doubt remains, or to obtain necessary histological evidence. © 2013 Éditions françaises de radiologie. Published by Elsevier Masson SAS. All rights reserved. Acute colitis is an acute condition of the colon and most often presents in the form of an acute abdominal picture with very variable clinical symptoms and laboratory test results. The most frequent symptoms encountered in colitis are abdominal pain, fever and diarrhoea [1]. Hyperleucocytosis and elevated CRP in laboratory tests are common. -

Abdominal Aortic Aneurysm (AAA)

Introduction NCEPOD operates under the umbrella of the National Patient Safety Agency (NPSA) as an independent confidential enquiry, whose main aim is to improve the quality and safety of patient care. Evidence is drawn from all sections of hospital activity in England, Wales, Northern Ireland, Guernsey, the Isle of Man and the Defence Sector, both NHS and private. We are very grateful to all those who take part as advisors, local reporters and as recipients of individual case reporting forms. I would also like to express my sincere thanks to our clinical co-ordinators and all the permanent staff of NCEPOD for the enormous amount of work and enthusiasm which they have put into the production of this report and without which we could not hope to perform such detailed analysis of, and comment upon, clinically-related hospital activity. Once again we have produced a summary report to accompany distribution of the detailed data both on CD ROM and also on the NCEPOD website, both of which allow major advances in the presentation of our data. Unlike traditional NCEPOD studies and in keeping with our new title of National Confidential Enquiry into Patient Outcome and Death, this is a cohort study looking at a specific area of clinical activity, namely, the management of abdominal aortic aneurysm (AAA). This was a fully representative sample of all patients admitted to hospital with an AAA during the study period, not just of those who died after operation, and thus provided us with good denominator data. There were 844 patients included in the study, 752 of which involved open operations, 53 of which involved endovascular repairs and 79 of which were patients who did not undergo operation but received palliative care. -

Angiogram, Balloon Angioplasty and Stent Placement for Peripheral Arterial Disease

Form: D-5093 Angiogram, Balloon Angioplasty and Stent Placement for Peripheral Arterial Disease What to expect before, during and after these procedures Check in at: Toronto General Hospital Medical Imaging Reception 1st Floor – Munk Building Date and time of my angiogram: Date: Time: My follow-up appointment: Date: Time: What is an angiogram? An angiogram is a test that lets your doctor see how your blood is flowing (circulating) through your arteries. Using special x-rays, an angiogram shows narrow or blocked arteries, and normal blood vessels. The results are like a “route map” of the blood vessels in your body. Since arteries do not show up on ordinary x-rays, a dye called a contrast is injected into the arteries to make them visible for a short period of time. Two common therapies that can be done during the angiogram are balloon angioplasty and stent placement. What is a balloon angioplasty? Angioplasty is an x-ray guided procedure to open up a blocked or narrowed artery. A plastic tube called a catheter is inserted close to the blocked or narrowed artery, helping a thin wire pass through the blockage or narrowing. A special balloon is then inserted over the wire. The balloon is inflated, flattening the plaque against the artery wall allowing blood to flow again. All balloons, wires and catheters are removed at the end of the procedure. blood vessel plaque inflated balloon balloon catheter 2 What is a stent placement? Sometimes a stent (a small metal mesh tube) is used with the balloon. The doctor places the stent into the artery to hold it open after it has been expanded with the balloon. -

Ischemic Colitis Caused by Polycythemia Vera: a Case Report and Literature Review

EXPERIMENTAL AND THERAPEUTIC MEDICINE 16: 3663-3667, 2018 Ischemic colitis caused by polycythemia vera: A case report and literature review SHASHA ZHANG1, RUIXUE LAI1, XUEQING GAO1, YUFEI ZHAO1, YUE ZHAO2, JIANHUA WU3 and ZHANJUN GUO1 Departments of 1Rheumatology and Immunology, and 2Gastroenterology and Hepatology, 3Animal Center, The Fourth Hospital of Hebei Medical University, Shijiazhuang, Hebei 050011, P.R. China Received January 16, 2018; Accepted August 10, 2018 DOI: 10.3892/etm.2018.6638 Abstract. Polycythemia vera (PV) is a chronic myeloproliferative Ischemic colitis (IC) can be described as an ischemic disease disorder originating from hematopoietic stem cells and of the colon, which results from decreased blood flow due to complicated by thrombosis and bleeding. This report describes a various causes that leads to intestinal wall ischemia, injury or case of ischemic colitis (IC) caused by PV and includes a review necrosis (3). The risk factors for IC mainly include diabetes, of the relevant literature. The patient was a 59-year-old male hypertension, dyslipidemia, peripheral vascular disease, with a history of PV who presented with abdominal pain and aspirin administration, and digoxin or constipation-inducing hematochezia. Colonoscopy and histopathological examination medications (4). The main clinical manifestations include results indicated suspected ischemic bowel disease. Following abdominal pain, diarrhea, and hematochezia (5). A reliable experimental anticoagulant therapy for 7 days, the patient no diagnosis of IC depends on the comprehensive evaluation of longer experienced abdominal pain and hematochezia had clinical symptoms, biochemical tests, radiological examina- resolved. Colonoscopy review showed no obvious anomalies tions, and endoscopic assessments (6). In certain cases, PV 1 month later. -

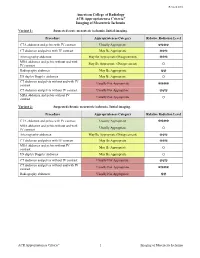

ACR Appropriateness Criteria® Imaging of Mesenteric Ischemia

Revised 2018 American College of Radiology ACR Appropriateness Criteria® Imaging of Mesenteric Ischemia Variant 1: Suspected acute mesenteric ischemia. Initial imaging. Procedure Appropriateness Category Relative Radiation Level CTA abdomen and pelvis with IV contrast Usually Appropriate ☢☢☢☢ CT abdomen and pelvis with IV contrast May Be Appropriate ☢☢☢ Arteriography abdomen May Be Appropriate (Disagreement) ☢☢☢ MRA abdomen and pelvis without and with May Be Appropriate (Disagreement) IV contrast O Radiography abdomen May Be Appropriate ☢☢ US duplex Doppler abdomen May Be Appropriate O CT abdomen and pelvis without and with IV Usually Not Appropriate contrast ☢☢☢☢ CT abdomen and pelvis without IV contrast Usually Not Appropriate ☢☢☢ MRA abdomen and pelvis without IV Usually Not Appropriate contrast O Variant 2: Suspected chronic mesenteric ischemia. Initial imaging. Procedure Appropriateness Category Relative Radiation Level CTA abdomen and pelvis with IV contrast Usually Appropriate ☢☢☢☢ MRA abdomen and pelvis without and with Usually Appropriate IV contrast O Arteriography abdomen May Be Appropriate (Disagreement) ☢☢☢ CT abdomen and pelvis with IV contrast May Be Appropriate ☢☢☢ MRA abdomen and pelvis without IV May Be Appropriate contrast O US duplex Doppler abdomen May Be Appropriate O CT abdomen and pelvis without IV contrast Usually Not Appropriate ☢☢☢ CT abdomen and pelvis without and with IV Usually Not Appropriate contrast ☢☢☢☢ Radiography abdomen Usually Not Appropriate ☢☢ ACR Appropriateness Criteria® 1 Imaging of Mesenteric Ischemia IMAGING OF MESENTERIC ISCHEMIA Expert Panels on Vascular Imaging and Gastrointestinal Imaging: Michael Ginsburg, MDa; Piotr Obara, MDb; Drew L. Lambert, MDc; Michael Hanley, MDd; Michael L. Steigner, MDe; Marc A. Camacho, MD, MSf; Ankur Chandra, MDg; Kevin J. Chang, MDh; Kenneth L.