APA Format 6Th Edition Template

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

ROOTS International Journal of Multidisciplinary Researches

M U O F L T I D A L I S N C R I P U L I O N J A L R A Y N R O E I S T E A R N C R H E E T S N I ROOTS ROOTS International Journal of Multidisciplinary Researches A Peer Reviewed, Refereed & Quarterly Journal Vol : 6 Special Issue 1 May 2020 ISSN : 2349-8684 CENTRE FOR RESOURCE, RESEARCH & PUBLICATION SERVICES (CRRPS) www.crrps.in ROOTS ROOTS International Journal of Multidisciplinary Researches (RIJMR) is a peer reviewed, refereed and quarterly journal. The Journal is assigned by National Science Library / NISCAIR, New Delhi and powered & published by Center for Resource, Research and Publication Services (CRRPS) Tamil Nadu - India. The journal provides a valid space for academics, researchers and professionals to share the latest developments and advancements in Multidisciplinary Subjects. It aims to foster the exchange of ideas on a range of important international subjects and to provide stimulus for research and further developments and updating of international perspectives. The international perspective is further enhanced and enriched by the geographical spread of the aspiring contributors. There are many practical reasons to publish research articles. We do not really understand what we have discovered until we write it up. When we submit an article for publication, we get back critical reviews from colleagues and readers, which undoubtedly can often be very helpful and sometimes, they point our mistakes or shortcomings in the applied logic therein. When we share the results of our efforts through publication, we become a part of the scientific community. -

Indian Cinema, Postcolonialism, and Social Justice: an Interview with Nandita Das1

Postcolonial Text, Vol 13, No 3 (2018) Indian Cinema, Postcolonialism, and Social Justice: An Interview with Nandita Das1 Manav Ratti Salisbury University, Maryland, USA Introduction Nandita Das (b. 1969) is one of India’s most eminent filmmakers and actors, renowned in particular for her work in art cinema (or parallel cinema, as it is also called in India), the genre of pioneering filmmakers Ritwik Ghatak (1925-1976), Satyajit Ray (1921-1992), Mrinal Sen (b. 1923), and Tapan Sinha (1924-2009). Das (Figure 1) has, in some respects, pursued an unconventional path into the Indian film industry, for it is not her first professional pursuit, and she does not hail from a film family (distinguished in their fields, her father, Jatin Das, is a painter; and her mother, Varsha Das, is a writer). Born in Mumbai and growing up in New Delhi, Das worked with NGOs for several years before entering the film industry, building on her Master’s degree from the Delhi School of Social Work in the University of Delhi. Fig. 1. Nandita Das at the Cannes Film Festival, 2017. Photo courtesy of Nandita Das Perhaps this unconventional, even outsider’s, path has informed Das’s use of films to question the norms of gender, religion, caste, sexuality, class, and nation, among others. Her work has gained recognition and respect for its uniqueness, urgency, awareness, and authenticity. Known for her social justice advocacy, Das’s national and international commitments span a range of issues, such as violence against women, children’s rights, HIV/AIDS, poverty, and interreligious harmony. She has supported India’s “Dark is Beautiful” campaign, which raises awareness about colourism, a form of prejudice and discrimination that devalues darker skin colours while privileging lighter ones. -

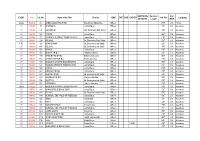

EVENT Year Lib. No. Name of the Film Director 35MM DCP BRD DVD/CD Sub-Title Language BETA/DVC Lenght B&W Gujrat Festival 553 ANDHA DIGANTHA (P

UMATIC/DG Duration/ Col./ EVENT Year Lib. No. Name of the Film Director 35MM DCP BRD DVD/CD Sub-Title Language BETA/DVC Lenght B&W Gujrat Festival 553 ANDHA DIGANTHA (P. B.) Man Mohan Mahapatra 06Reels HST Col. Oriya I. P. 1982-83 73 APAROOPA Jahnu Barua 07Reels EST Col. Assamese I. P. 1985-86 201 AGNISNAAN DR. Bhabendra Nath Saikia 09Reels EST Col. Assamese I. P. 1986-87 242 PAPORI Jahnu Barua 07Reels EST Col. Assamese I. P. 1987-88 252 HALODHIA CHORAYE BAODHAN KHAI Jahnu Barua 07Reels EST Col. Assamese I. P. 1988-89 294 KOLAHAL Dr. Bhabendra Nath Saikia 06Reels EST Col. Assamese F.O.I. 1985-86 429 AGANISNAAN Dr. Bhabendranath Saikia 09Reels EST Col. Assamese I. P. 1988-89 440 KOLAHAL Dr. Bhabendranath Saikia 06Reels SST Col. Assamese I. P. 1989-90 450 BANANI Jahnu Barua 06Reels EST Col. Assamese I. P. 1996-97 483 ADAJYA (P. B.) Satwana Bardoloi 05Reels EST Col. Assamese I. P. 1996-97 494 RAAG BIRAG (P. B.) Bidyut Chakravarty 06Reels EST Col. Assamese I. P. 1996-97 500 HASTIR KANYA(P. B.) Prabin Hazarika 03Reels EST Col. Assamese I. P. 1987-88 509 HALODHIA CHORYE BAODHAN KHAI Jahnu Barua 07Reels EST Col. Assamese I. P. 1987-88 522 HALODIA CHORAYE BAODHAN KHAI Jahnu Barua 07Reels FST Col. Assamese I. P. 1990-91 574 BANANI Jahnu Barua 12Reels HST Col. Assamese I. P. 1991-92 660 FIRINGOTI (P. B.) Jahnu Barua 06Reels EST Col. Assamese I. P. 1992-93 692 SAROTHI (P. B.) Dr. Bhabendranath Saikia 05Reels EST Col. -

Blessed Is the Rural Hospital Good Doctors

VOL. 18 NO. 9 JULY 2021 www.civilsocietyonline.com .com/civilsocietyonline `80 BLESSED IS THE RURAL HOSPITAL How to take better care to villages BLESSED IS THE RURAL HOSPITAL Deepak and Ashita Singh at the Chinchpada Christian Hospital LAKshadweep’s future INTERVIEW IT IS A TIME TO SPEND Page 8 ‘NGOs tANGLED UP Page 35 HYPERLOCAL REPORTING IN MESSy rules’ TAMIL’s defiant fiLMS Page 10 Page 41 HARSH JAITLI EXPLAINS WHY THE THE GREEN CASHEW NUT VOLUNTARY SECTOR IS SHRINKING ETHICAL CHEESE & MORE Page 16 Page 6 Page 45 IN CIVIL SOCIETY EVERYONE IS SOMEONE R E A D U S. W E R E A D Y O U. For 17 years, month after month. Thousands of original stories. Faces on our covers you would not otherwise have seen. VOICES CONTENTS yielding financial gains. Then why SAMITA RATHOR did we choose this model? IN THE LIGHT Dipankar Dasgupta Goa tourism I read Derek Almeida’s article, ‘Does R E A D U S. W E R E A D Y O U. Goa have a future without mass tourism?’ on your website. Very illuminating piece. From an exclusive hippie destination of the 1960s, Goa has steadily turned into a mass tourist Pandemic and us destination. On a recent visit, after 30 years, I noticed more bus-loads of T has been more than a year and the pandemic continues to serve up penny-conscious tourists from Isurprises. Losing friends and worrying about those who are unwell has neighbouring states than foreigners been unsettling. Multiple lockdowns and severely restricted mobility have or big spenders. -

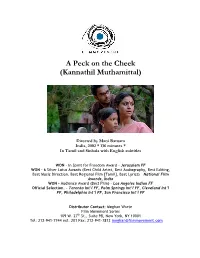

A Peck on the Cheek (Kannathil Muthamittal)

A Peck on the Cheek (Kannathil Muthamittal) Directed by Mani Ratnam India, 2002 * 136 minutes * In Tamil and Sinhala with English subtitles WON - In Spirit for Freedom Award – Jerusalem FF WON – 6 Silver Lotus Awards (Best Child Artist, Best Audiography, Best Editing, Best Music Direction, Best Regional Film [Tamil], Best Lyrics) – National Film Awards, India WON – Audience Award (Best Film) – Los Angeles Indian FF Official Selection. – Toronto Int’l FF, Palm Springs Int’l FF, Cleveland Int’l FF, Philadelphia Int’l FF, San Francisco Int’l FF Distributor Contact: Meghan Wurtz Film Movement Series 109 W. 27th St., Suite 9B, New York, NY 10001 Tel: 212-941-7744 ext. 201 Fax: 212-941-7812 [email protected] Film Synopsis: A little girl's search for her biological mother who had abandoned her as a newborn baby is brought out poignantly in 'Kannathil Muthamittal'. With films like 'Mouna Ragam', 'Alaipayuthe' and now 'Kannathil Muthamittal', Maniratnam yet again proves that he is at his best when tackling human emotions and relationships. Amudha, adopted by Thiru and Indira and growing up with the couple’s two sons, is blissfully unaware of her parentage, until the couple decides to inform her of it on her ninth birthday. At first shocked into disbelief, Amudha then expresses her determination to seek out for her biological mother. The search takes the family to strife- torn Sri Lanka, where Amudha comes face-to-face with reality, and reconciles herself to it. Credits: Cast: Mani Ratnam… writer/director/producer R. Madhavan… Thiruchelvan G. Srinivasan… producer Simran (alias) Rishi Novel… Indira Ravi K. -

Negotiating Identities in the Diasporic Space: Transnational Tamil Cinema and Malaysian Indians

Negotiating identities in the Diasporic Space: Transnational Tamil Cinema and Malaysian Indians Gopalan Ravindran Abstract One of the significant transformations brought about by globalization is the transnationalization of diasporic cinemas. A case in point is the growth of diasporic cinemas catering to the varied diasporas of Indian origin. One of the most important diasporas cinema is Tamil cinema. Negotiations of identities in the Tamil diasporic space are mediated by a variety of sources ranging from Tamil films, Tamil internet, Tamil satellite television/radio and Tamil newspapers/magazines, beside interpersonal sources. Even though, studies have not been done on the relative influence of the above sources, it is apparent that in countries like Malaysia and Singapore, Tamils films are having a perceptible influence among different sections of the Indian population. This paper aims to examine the role of transnational Tamil cinema in Malaysia with a focus on Malaysian Tamil cinema audience's negotiations of cultural identities in the diasporic space Cultural Space and Public Sphere in Asia 2006, Seoul, Korea / 240 Introduction The notion of film spectators is bridled with as many adequacies as there are inadequacies. The plight of the notion of film audience is no different. Notwithstanding the seemingly simple similarity between the two, there are divergent views of their locations (Meers,2001; Fuller-Seeley,2001) While the film spectator is positioned as the dreaming and individualistic psychological material before the screen (Rascaroli,2002), members of film audience are seen as belonging to collectives that are constituted by socio-cultural conditions. Such collectives are also recognizable, empirically and otherwise; in contrast to the dreaming film spectators. -

CURRICULUM VITAE Department of South and South East Asian Studies University of California Berkeley Dwinelle Hall Email: [email protected]

Kailasam, Feb 2020 VASUGI KAILASAM CURRICULUM VITAE Department of South and South East Asian Studies University of California Berkeley Dwinelle Hall Email: [email protected] EDUCATION 2015 PhD, Department of English Language and Literature, National University of Singapore. 2009 Masters in Comparative Literature (Asia/Africa), SOAS, University of London. 2007 Bachelors in English Literature, Stella Maris College, University of Madras. PROFESSIONAL APPOINTMENTS July 2019 – present Assistant Professor, Department of South and South East Asian Studies (SSEAS), University of California, Berkeley. Aug 2015 – June 2019 Lecturer, South Asian Studies Programme (SASP), National University of Singapore. PUBLICATIONS Peer Reviewed Journal Articles Forthcoming “Reimagining Postcolonial Sri Lanka as ‘Ceylon’: Shyam Selvadurai’s Cinnamon Gardens” in ARIEL Forthcoming “Becoming an engineer, becoming a Tamil man: The middle-class hero in post-millennial Tamil cinema” in Tamil Cinema in the 21st Century: Politics, Genre and Technology, edited by Vijay Devdas and Selvaraj Velayutham (Routledge Press) 2018 “Sri Lankan Tamil nationalism and male violence: The unnarratability of Shobasakthi’s Traitor” in Journal of Commonwealth Literature. 2017 “Framing the Neo- Noir in Contemporary Tamil Cinema: Masculinity and Modernity in Tamil Nadu” in South Asian Popular Culture, 15 (1), pp. 23-39 2015 “Notes on a South Asian Diasporic Aesthetic: Reading Cheran Rudramoorthy’s Poetry” in Postcolonial Text, Chakraborty, Chandima. ed. Translated Worlds: History, Diaspora, South Asia (special issue in honour and memory of Chelva Kanaganayagam) Volume 10&11, Issue 3. pp 1-18. Encyclopaedia Entries 2013 “Cinema and the Sri Lankan Diaspora” in The Encyclopaedia of the Sri Lankan Diaspora, eds. Peter Reeves and Rajesh Rai, editions Didier Millet, Singapore 2013. -

Research Scholar ISSN 2320 – 6101 an International Refereed E-Journal of Literary Explorations Impact Factor 0.998 (IIFS)

Research Scholar ISSN 2320 – 6101 www.researchscholar.co.in An International Refereed e-Journal of Literary Explorations Impact Factor 0.998 (IIFS) SCREEN SHIFTS IN RECENT TAMIL CINEMAS: THE “NEW” NEW WAVE Nithin Kalorth Research Scholar, School of Social Sciences MG University, Kottayam, Kerala Abstract A new wave in Tamil cinema is happening on screen which contrasts conventional film style of Tamil Nadu. A visible layer of difference between urban and rural identity and new perspectives of nationhood is being seen in Tamil cinema. The formulas of films are shifting and it can see from the presentation of the character in the marketing of the film. This paper tries to understand the characteristics and outline the Tamil new generation (new wave) cinema. Keywords: Tamil cinema, new wave, culture Introduction Tamil Nadu and Tamil cinema are unified in many ways and its relation is omnipresent. The gap between the culture of Tamil Nadu and that of Tamil film going audience are blurred for the ages. Audience, more appropriately fans of Tamil cinema actors and actress perceive actor and actress as god and goddess; build temples as their token of love. “They not only love, but worship” (Raman, 2012). The Tamil audience influenced cinema majorly by the actors and their glory. Films which highlight actors as “superheroes” are mainly commercial and laid the conventional basis for Tamil cinema for long decades. The image of the hero is not restricted within the screen, but also off screen. They become part of their culture and identity. This is a trend that has been happening for a very long time in Tamil Cinema (Changing Trends - Is Tamil cinema coming of age, 2008). -

Master World Cinema Spreadsheet No Id#'S

WORLD CINEMA TITLE LANGUAGE LOCATION 24 Hours of Love Arabic Farmington Community Library Abouna (Our Father) Arabic West Bloomfield Public Library Addict Arabic West Bloomfield Public Library Adrift on the Nile Arabic Baldwin Public Library Adrift on the Nile Arabic Farmington Community Library Adrift on the Nile Arabic West Bloomfield Public Library Africano Arabic West Bloomfield Public Library Afrita Hanem Arabic Rochester Hills Public Library Ala Bab Al Wazeer Arabic Rochester Hills Public Library Alexandria Again and Forever Arabic West Bloomfield Public Library Alexandria…Why? Arabic West Bloomfield Public Library Ali Zaoua Arabic West Bloomfield Public Library Asker Fel-Moasker Arabic Rochester Hills Public Library Away from Land Arabic Baldwin Public Library Bab El-Oued City Arabic Farmington Community Library Bad Guys Arabic Farmington Community Library Beach Bum Arabic Baldwin Public Library Best of Times Arabic Farmington Community Library Boy of Baghdad Arabic Farmington Community Library Checkpoint Arabic Baldwin Public Library Checkpoint Arabic Rochester Hills Public Library Citizen, a Dectective, and a Thief Arabic Baldwin Public Library Closed doors Arabic Rochester Hills Public Library Color of Olives Arabic West Bloomfield Public Library Cool Man Arabic West Bloomfield Public Library Dananeer Arabic Farmington Community Library Daresalam Arabic Farmington Community Library Date with the Unknown Arabic West Bloomfield Public Library Daughter of Keltoum Arabic Baldwin Public Library Days & nights Arabic Farmington Community -

Space-Time Formations in the South Indian Tamil Popular Film Kannathil Muthamittal

IJAPS, Vol. 14, No. 2, 143–164, 2018 SPACE-TIME FORMATIONS IN THE SOUTH INDIAN TAMIL POPULAR FILM KANNATHIL MUTHAMITTAL Ramesh Loganathan* Faculty of Social Sciences and Humanities, Universiti Kebangsaan Malaysia, 43600 UKM Bangi, Selangor, Malaysia e-mail: [email protected] Shanthini Pillai** Faculty of Social Sciences and Humanities, Universiti Kebangsaan Malaysia, 43600 UKM Bangi, Selangor, Malaysia e-mail: [email protected] Pramela Krish*** Faculty of Social Sciences and Humanities, Universiti Kebangsaan Malaysia, 43600 UKM Bangi, Selangor, Malaysia e-mail: [email protected] Published online: 15 July 2018 To cite this article: Loganathan, R., Pillai, S. and Krish, P. 2018. Space-time formations in the South Indian Tamil popular film Kannathil Muthamittal. International Journal of Asia Pacific Studies 14 (2): 143–164, https://doi.org/ 10.21315/ijaps2018.14.2.7 To link to this article: https://doi.org/10.21315/ijaps2018.14.2.7 ABSTRACT In tandem with the current development of film scholarships in the area of the world and national cinemas, the paper seeks to examine four scenes from the South Indian Tamil popular film “Kannathil Muthamittal” (English: A Peck on the Cheek) using a concept derived from Hamid Naficy’s theorisation of an accented cinema known as the filmmakers’ “preoccupation with the place.” The conception is cinematically expressed through spatial representations of the open, closed and the third space- time formations. In the accented cinema, space-time formations are cinematic spatial aspects that are employed to produce or reproduce the fundamental “accent” of displacement and deterritorialisation. According to Naficy, the accent predominantly originates from the filmmakers’ experiences and their artisanal productions and not so much from their accented lingo. -

DIRECTORS: Satyajit Ray Satyajit Ray Directed 36 Films, Including

DIRECTORS: Satyajit Ray Satyajit Ray directed 36 films, including feature films, documentaries and shorts.. Ray received many major awards in his career, including 32 Indian National Film Awards, a number of awards at international film festivals and award ceremonies, and an honorary Academy Award in 1992. Satyajit Ray's films are both cinematic and literary at the same time; using a simple narrative, usually in a classical format, but greatly detailed and operating at many levels of interpretation. His first film, Pather Panchali (Song of the little road, 1955) established his reputation as a major film director, winning numerous awards including Best Human Document, Cannes, 1956 and Best Film, Vancouver, 1958. It is the first film of a trilogy - The Apu Trilogy - a three-part tale of a boy's life from birth through manhood. The other two films of this trilogy are Aparajito (The Unvanquished, 1956) and Apur Sansar (The World of Apu, 1959). His later films include Jalsaghar (The Music Room, 1958), Devi (The Goddess, 1960), Teen Kanya (Two Daughters, 1961),Charulata (The Lonely Wife, 1964), Nayak (The Hero, 1966), Asani Sanket (Distant Thunder, 1973), Shatranj Ke Khilari(The Chess Players, 1977), Ghare Baire (The Home and the World, 1984), Ganashatru (An Enemy Of The People, 1989) and Shakha Prashakha (Branches Of The Tree, 1991). Agantuk (The Stranger, 1991) was his last film. Mahesh Bhatt Mahesh Bhatt is a prominent Indian film director, producer and screenwriter. Bhatt's early directional career consisted of acclaimed movies, such as Arth, Saaransh, Janam, Naam, Sadak and Zakhm. He was later the writer of numerous commercial films in a range of genres, from dramas like Hum Hain Rahi Pyar Ke and comedies like Duplicate, though he was mostly recognised for thrillers like Inteha, Jism, Murder and Woh Lamhe. -

Letter from the President

Letter from the President Dear Colleagues, Welcome to Seattle and the Seattle Sheraton Hotel for the 54th annual SCMS Conference. On behalf of the SCMS Board of Directors, the Home Office, the Sheraton Hotel, the Seattle Host Committee, and the consultants and volunteers who have helped to create this conference, let me say that we are delighted that you are here. We hope that the conference and city will lead to discoveries that are intellectually stimulating and socially rewarding and that will satisfy your inner urban explorer. The Host Committee, co-chaired by Jennifer Bean and Kaveh Askari, have worked hard to provide an imaginative and engaging experience for conference goers who are coming to Seattle for the first time as well as for those who might be seasoned veterans. Thank you Jennifer and Kaveh! In addition to the conference’s offerings of panels and workshops, there are a number of other events during the confer- ence that we hope you will be able to attend. The Awards Ceremony is one of the most significant means SCMS has of formally recognizing the accomplishments of our colleagues in research, teaching, and service in the field each year. This year, the ceremony will be held on Friday, March 21st from 4:15 – 5:30 PM. All members are welcome—please plan to be there to join in the celebration. While I cannot mention all of the award winners here, I am happy to announce that Richard Abel has won the Distinguished Career Achievement Award. Given his pioneering research and teaching in film history and on the early and silent cinemas of France and the US, it would be hard to overestimate the impact his impeccable work has had on the field.