Community Based Tourism in Kimmirut, Baffin Island, Nunavut: Regional Versus Local Attitudes

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Tourism in Destination Communities

Color profile: Disabled Composite Default screen Tourism in Destination Communities 1 Z:\Customer\CABI\A4398 - Singh\A4456 - Singh - First Revise A.vp Tuesday, December 10, 2002 12:18:07 PM Color profile: Disabled Composite Default screen 2 Z:\Customer\CABI\A4398 - Singh\A4456 - Singh - First Revise A.vp Tuesday, December 10, 2002 12:18:07 PM Color profile: Disabled Composite Default screen Tourism in Destination Communities Edited by S. Singh Department of Recreation and Leisure Studies Brock University Canada and Centre for Tourism Research and Development Lucknow India D.J. Timothy Department of Recreation Management and Tourism Arizona State University USA and R.K. Dowling School of Marketing, Tourism and Leisure Edith Cowan University Joondalup Australia CABI Publishing 3 Z:\Customer\CABI\A4398 - Singh\A4456 - Singh - First Revise A.vp Friday, January 03, 2003 1:52:23 PM Color profile: Disabled Composite Default screen CABI Publishing is a division of CAB International CABI Publishing CABI Publishing CAB International 44 Brattle Street Wallingford 4th Floor Oxon OX10 8DE Cambridge, MA 02138 UK USA Tel: +44 (0)1491 832111 Tel: +1 617 395 4056 Fax: +44 (0)1491 833508 Fax: +1 617 354 6875 E-mail: [email protected] E-mail: [email protected] Web site: www.cabi-publishing.org ©CAB International 2003. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced in any form or by any means, electronically, mechanically, by photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the copyright owners. A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library, London, UK. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Tourism in destination communities / edited by S. -

Perspectives of Decision Makers and Regulators on Climate Change and Adaptation in Expedition Cruise Ship Tourism in Nunavut

Perspectives of Decision Makers and Regulators on Climate Change and Adaptation in Expedition Cruise Ship Tourism in Nunavut Adrianne Johnston, Margaret Johnston, Emma Stewart, Jackie Dawson, Harvey Lemelin Abstract: Increases in Arctic tourism over the past few decades have occurred within a context of change, including climate change. This article examines the ways in which tourism decision makers and regulators in Nunavut view the interactions of cruise ship tourism and climate change, the challenges presented by those interactions, and the opportunities available within this context of change. The article uses an approach that is aimed at assessing sensitivities and adaptive capacity in order to develop strategies for managing change. It describes the findings from thirty-one semi-structured interviews conducted with federal government, Government of Nunavut, and industry personnel and managers involved in Nunavut’s tourism industry. The two major themes of the article are the growth and adjustment in the cruise tourism industry stemming from climate change and the governance issues that are associated with these changes. A strong focus in the interviews was recognition of the need for a collaborative approach to managing the industry and the need to enhance and extend territorial legislation to ensure a safe and coordinated industry to provide benefit to Nunavut, the communities that host the ships, the industry, and the tourists. The article concludes that decision makers and regulators need to address the compounding of challenges arising from tourism and climate change through a multi-level stakeholder approach. Change, flexibility, and adaptation in tourism have become a major focus in northern regions as global environmental, political, economic, and social forces influence both the supply- and demand-sides of the industry. -

Cruising the Marginal Ice Zone: Climate Change and Arctic Tourism David Palma A, Alix Varnajot B, Kari Dalenc, Ilker K

POLAR GEOGRAPHY https://doi.org/10.1080/1088937X.2019.1648585 Cruising the marginal ice zone: climate change and Arctic tourism David Palma a, Alix Varnajot b, Kari Dalenc, Ilker K. Basarand, Charles Brunette e, Marta Bystrowska f, Anastasia D. Korablina g, Robynne C. Nowickih and Thomas A. Ronge i aDepartment of Information Security and Communication Technology, NTNU – Norwegian University of Science and Technology, Trondheim, Norway; bGeography Research Unit, University of Oulu, Oulu, Finland; cIndependent Researcher, Oslo, Norway; dIMO-International Maritime Law Institute, Msida, Malta; eDepartment of Atmospheric and Oceanic Sciences, McGill University, Montreal, Canada; fDepartment of Earth Sciences, University of Silesia in Katowice, Sosnowiec, Poland; gDepartment of Oceanology, Faculty of Geography, Lomonosov Moscow State University, Moscow, Russia; hDepartment of Ocean and Earth Sciences, University of Southampton, Southampton, UK; iDepartment of Marine Geology, Alfred-Wegener-Institut Helmholtz Zentrum für Polar- und Meeresforschung, Bremerhaven, Germany ABSTRACT ARTICLE HISTORY The effects of climate change are leading to pronounced physical and Received 19 October 2018 ecological changes in the Arctic Marginal Ice Zone (MIZ). These are not Accepted 21 May 2019 only of concern for the research community but also for the tourism industry dependent on this unique marine ecosystem. Tourists KEYWORDS Marginal ice zone; Arctic increasingly become aware that the Arctic as we know it may tourism; Arctic Ocean; cruise disappear due to several environmental threats, and want to visit the tourism; climate change region before it becomes irrevocably changed. However, ‘last-chance tourism’ in this region faces several challenges. The lack of infrastructure and appropriate search and rescue policies are examples of existing issues in such a remote location. -

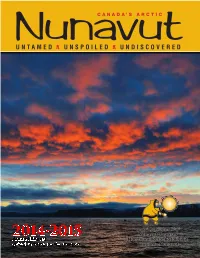

A Tourism Strategy for Nunavummiut

Tunngasaiji: A Tourism Strategy for Nunavummiut Tunngasaiji 01 ISBN 978-1-55325-252-8 Cover photography credit; clockwise from top left: Christian Kimber, Nunavut Tourism, David Kilabuk (models; Priscilla Angnakak,left Nadia Metuq,right), Nunavut Tourism Photo Courtesy of Heiner Kubny Tunngasaiji: A Tourism Strategy for Nunavummiut A Message from the Minister of Economic Development and Transportation I am pleased and honoured to welcome readers to must be built on a foundation of quality tourism Tunngasaiji: A Tourism Strategy for Nunavummiut. products and services, supported by training and education, resources for marketing and promotion, and There is something very special about the tourism a supportive, effective framework of legislation and industry. It is an essential pillar of our territorial regulation. economy. But it is also a celebration of everything that makes Nunavut unique – a reflection of the beauty To address that need, we called on the experience and and diversity of our Arctic lands, the richness of our insight of Nunavummiut, and of their organizations and history, the depth of our culture, and the warmth and government. Tunngasaiji owes much to the patience hospitality of our people. Tourism is a celebration and a and commitment of the many people who generously sharing of who we are, an opportunity to welcome the shared their time and their ideas. The strength of the world as hosts, as guides, and as friends. strategy is a tribute to their contribution. Tunngasaiji responds to a need that our communities We have been endowed by history and nature with a and businesses have expressed for many years. -

Strategic Development Challenges in Marine Tourism in Nunavut

resources Article Strategic Development Challenges in Marine Tourism in Nunavut Margaret E. Johnston 1,*, Jackie Dawson 2 and Patrick T. Maher 3 1 School of Outdoor Recreation, Parks and Tourism, Lakehead University, Thunder Bay, ON P7B 5E1, Canada 2 Department of Geography, Environment, and Geomatics, University of Ottawa, Ottawa, ON K1N 6N5, Canada; [email protected] 3 School of Arts and Social Sciences, Cape Breton University, Sydney, NS B1P 6L2, Canada; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +1-807-343-8377 Received: 30 May 2017; Accepted: 26 June 2017; Published: 30 June 2017 Abstract: Marine tourism in Arctic Canada has grown substantially since 2005. Though there are social, economic and cultural opportunities associated with industry growth, climate change and a range of environmental risks and other problems present significant management challenges. This paper describes the growth in cruise tourism and pleasure craft travel in Canada’s Nunavut Territory and then outlines issues and concerns related to existing management of both cruise and pleasure craft tourism. Strengths and areas for improvement are identified and recommendations for enhancing the cruise and pleasure craft governance regimes through strategic management are provided. Key strategic approaches discussed are: (1) streamlining the regulatory framework; (2) improving marine tourism data collection and analysis for decision-making; and (3) developing site guidelines and behaviour guidelines. Keywords: marine tourism; cruise ships; pleasure craft; Nunavut Territory; management; impacts; Arctic Canada 1. Introduction Marine tourism in the Arctic has been growing as tourism demand increases and accessibility is improved [1–3]. Much of this activity involves smaller expedition cruise ships and the larger vessels common in more accessible cruise destinations. -

Cruise Tourism in a Warming Arctic: Implications for Northern National Parks

Cruise tourism in a warming Arctic: Implications for northern National Parks ,2 1 4 E. J. STEWART1 , S.E.L. HOWELL3, D. DRAPER , J. YACKEL4 and A. TIVY Abstract: This research examines patterns of cruise travel through the Canadian Arctic between 1984-2008 with an emphasis on shore visits to the northern National Parks of Sirmilik, Auyuittuq and Quttinirpaaq. Given the warming effects of climate change, we investigate claims regarding accelerated growth of cruise tourism in Arctic Canada, and the implications this anticipated ‘growth’ may have for northern National Parks. We also caution that as the transition to an ice-free Arctic summer continues, the prevalence of hazardous, multi-year ice conditions likely will continue to have negative implications for cruise travel in the Canadian Arctic, and in particular for tourist transits through the Northwest Passage and High Arctic regions. Introduction With a goal to protect natural areas representative of Canada’s ecoregions (Marsh, 2000), three National Parks have been established in Nunavut, Canada’s most northerly territory (see Figure 1). Auyuittuq National Park on Baffin Island was established in 1976, Sirmilik National Park also on Baffin Island was designated in 1999 when Nunavut was created, and Quttinirpaaq National Park, (established initially as Ellesmere Island National Park Reserve in 1988), had its name changed to Quttinirpaaq in 1999 and became a national park in 2000. For a variety of reasons, northern parks attract relatively few visitors compared to other national parks in Canada (Marsh, 2000). However, protected natural areas (including national parks and wildlife areas) are attractive destinations for cruise operators and their clients, not only because of their natural and cultural interest, but because all of Nunavut’s National Parks have a shoreline, making them accessible to cruise vessels (Marquez & Eagles, 2007). -

Annual-Report-2009-10-English.Pdf

Table of Contents Message from the Chair ................................................................................................................................................. i CEO’s Report .................................................................................................................................................................. ii Vision, Mission and Background .................................................................................................................................... 2 Marketing & Communications ....................................................................................................................................... 3 Member Services ........................................................................................................................................................... 7 Visitor Services............................................................................................................................................................... 8 Operations & Management ........................................................................................................................................... 9 Appendices Appendix A: Board of Directors Appendix B: Nunavut Tourism Staff Appendix C: Membership List Appendix D: Financial Statements Message from the Chair Unnusakkut everyone!! Let me start with some numbers. Tourism in Nunavut was up 10.6 % this summer over last year. Nunavut Tourism membership has more than doubled since this time last -

Tourists' Practices and Perceptions of the Arctic in Rovaniemi

Nordia Geographical Publications Volume 49:4 Rethinking Arctic tourism: tourists’ practices and perceptions of the Arctic in Rovaniemi Alix Varnajot ACADEMIC DISSERTATION to be presented with the permission of the Doctoral Training Committee for Human Sciences of the University of Oulu Graduate School (UniOGS), for public discussion in the lecture hall L10, on the 4th of September, 2020, at 15 afternoon. Nordia Geographical Publications Volume 49:4 Rethinking Arctic tourism: tourists’ practices and perceptions of the Arctic in Rovaniemi Alix Varnajot Nordia Geographical Publications Publications of The Geographical Society of Northern Finland and Geography Research Unit, University of Oulu Address: Geography Research Unit P.O. Box 3000 FIN-90014 University of Oulu FINLAND [email protected] Editor: Teijo Klemettilä Nordia Geographical Publications ISBN 978-952-62-2691-0 ISSN 1238-2086 PunaMusta Tampere 2020 Rethinking Arctic tourism: tourists’ practices and perceptions of the Arctic in Rovaniemi Contents Abstract vii List of original articles x Acknowledgements xi 1 Introduction 1 2 Purpose and structure of the research 5 2.1 Aim of the research 5 2.2 Structure of the thesis 6 2.3 Situating the thesis and the articles 8 3 The Arctic in tourism 11 3.1 A quest for defining the Arctic and Arctic tourism 11 3.2 The state of tourism in the Arctic 17 4 Research materials and methods 25 4.1 Case study: Rovaniemi 25 4.2 Research method inspired from multiple ethnographies 30 4.3 Data analysis 38 5 Framing Arctic tourist experiences: crossing -

Ecotourism Emerging Industry Forum Organized by Planeta.Com and Eplerwood International November 1-18, 2005

Ecotourism Emerging Industry Forum Organized by Planeta.com and EplerWood International November 1-18, 2005 Funded by participants, the SNV Netherlands Development Organisation, Conservation International and Balam Consultores. Additional support comes from USAID, and the Development Gateway. Ecotourism Emerging Industry Forum 1 Table of Contents Preface Navigating the Document Executive Summary Thank You’s Ecotourism Emerging Industry Forum Transcript Chatter and general introductions • See List of Participants Developing Infrastructure for Sustainable Tourism Moderator: Oliver Hillel • Weekly Summary • Case Studies o Shompole in Southern Kenya o Black Sheep Inn, Ecuador o Cree Village Ecolodge, Canada o Wa-sh-ow James Bay Wilderness Centre, Canada • Donor Recommendations Private sector/Public sector collaboration Moderator: Steve Noakes • Weekly Summary • Case Studies o The Quu'as West Coast Trail Society, Canada o Clayoquot Sound World Biosphere Reserve, Canada o Haida Gwaii, Queen Charlotte Islands, Canada • Donor Recommendations Finance for SMEs Moderator: Jeanine Corvetto • Weekly Summary • Case Studies o FRi Ecological Services (Ron Bilz), Canada o Canyon Travel, Mexico • Donor Recommendations Communities and SMEs Moderator: Nicole Haeusler • Weekly Summary • Case Studies o Wigsten on his experience in Sweden, Mongolia, Suriname and Estonia o Wigsten on Mongolia o Maasailand Experience, Kenya & Tanzania o Pangnirtung and other Inuit communities in Nunavut, Canada o Tropic - Journeys in Nature, Ecuador o Cree Village Ecolodge, Canada -

Indigenous Ecotourism

Indigenous Ecotourism Sustainable Development and Management DEDICATION To my father – Mervin Vernon Zeppel (13 July 1922–26 September 2005) and for S.T.M. (for your Cree and Ojibway heart) Ecotourism Book Series General Editor: David B. Weaver, Professor of Tourism Management, George Mason University, Virginia, USA. Ecotourism, or nature-based tourism that is managed to be learning-oriented as well as environ- mentally and socio-culturally sustainable, has emerged in the past 20 years as one of the most important sectors within the global tourism industry. The purpose of this series is to provide diverse stakeholders (e.g. academics, graduate and senior undergraduate students, practitioners, protected area managers, government and non-governmental organizations) with state-of-the-art and scientifically sound strategic knowledge about all facets of ecotourism, including external environments that influence its development. Contributions adopt a holistic, critical and interdisci- plinary approach that combines relevant theory and practice while placing case studies from specific destinations into an international context. The series supports the development and diffu- sion of financially viable ecotourism that fulfils the objective of environmental, socio-cultural and economic sustainability at both the local and global scale. Titles available: 1. Nature-based Tourism, Environment and Land Management Edited by R. Buckley, C. Pickering and D. Weaver 2. Environmental Impacts of Ecotourism Edited by R. Buckley 3. Indigenous Ecotourism: Sustainable -

2014-15 Appendix G: Financial Statements – Inuktitut Appendix D: Inuit Language Plan Appendix H: Financial Statements – English Message from the Chair

2014-2015Annual Report ᐊᕐᕌᒍᑕᒫᖅᓯᐅᑎᖓ ᐅᓂᒃᑳᓕᐊᖑᓯᒪᔪᖅ Message from the Chair ................................................................................................................................................ 1 CEO’s Report .................................................................................................................................................................. 2 Vision, Mission and Background ................................................................................................................................... 4 Marketing & Communications ...................................................................................................................................... 5 Tourism in Nunavut Conference 2015.............................................................................................................................. 5 Member Services ......................................................................................................................................................... 16 Visitor Centres ............................................................................................................................................................ 18 Operations & Management ......................................................................................................................................... 20 Appendices Appendix A: Board of Directors Appendix E: Inuit Employment Plan Appendix B: Nunavut Tourism Staff Appendix F: Member List Appendix C: CEO Travel 2014-15 -

Sustainable Tourism and Natural Resource Conservation in the Polar Regions

Sustainable Tourism and Natural Resource Conservation in the Polar Regions Edited by Machiel Lamers and Edward Huijbens Printed Edition of the Special Issue Published in Resources www.mdpi.com/journal/resources Sustainable Tourism and Natural Resource Conservation in the Polar Regions Sustainable Tourism and Natural Resource Conservation in the Polar Regions Special Issue Editors Machiel Lamers Edward Huijbens MDPI • Basel • Beijing • Wuhan • Barcelona • Belgrade Special Issue Editors Machiel Lamers Edward Huijbens Wageningen University University of Akureyri The Netherlands Iceland Editorial Office MDPI St. Alban-Anlage 66 Basel, Switzerland This is a reprint of articles from the Special Issue published online in the open access journal Resources (ISSN 2079-9276) in 2017 (available at: http://www.mdpi.com/journal/resources/special issues/ polar tourism) For citation purposes, cite each article independently as indicated on the article page online and as indicated below: LastName, A.A.; LastName, B.B.; LastName, C.C. Article Title. Journal Name Year, Article Number, Page Range. ISBN 978-3-03897-011-8 (Pbk) ISBN 978-3-03897-012-5 (PDF) Articles in this volume are Open Access and distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license, which allows users to download, copy and build upon published articles even for commercial purposes, as long as the author and publisher are properly credited, which ensures maximum dissemination and a wider impact of our publications. The book taken as a whole is c 2018 MDPI, Basel, Switzerland, distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons license CC BY-NC-ND (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/).