The Judge As Author / the Author As Judge, 40 Golden Gate U

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Civilian Conservation Corps at Camp SP-12, Fort Necessity, Farmington, PA

TECHNICALINFORMATIONCENTE~ DENVERSERVICECENTER NATIONALPARKSERVICE - * FORT NECESSITY CIVILIAN CONSERVATIONCORPS CAMP SP-12 1935-1937 bY Larry N. Sypolt ~'November 15, 1988 Morgantown, WV I Preface This paper is meant to be an administrative history of the Civilian Conservation Corps at Camp SP-12, Fort Necessity, Farmington, PA. The CCC camp at Fort Necessity existed for only two and one-half years, from June 1935, through December 1937. This oral history project was conducted with people who served the CCC program at Fort Necessity during those years. I have gotten interviews from a camp advisor, camp military officer, local experienced man, work leader and enrollees, the purpose of which was to yet an idea of what this experience meant to people at all levels. The first section opens with a brief overview of the CCC program in general. No attempt was made here to tell its whole story, as many books have already been written on the subject. This overview is followed by the administrative history at Fort Necessity, with papers following that are of particular interest to the camp. The second section contains the edited transcripts of the interviews. It is followed by some written interviews sent by people some distance away or who were not available for an oral interview. A list of questions is contained with their answers. I would also like to take this time to thank all those who helped me with this~,"project. A special thanks to Bill Fink and his staff at -Fort Necessity National Battlefield for all of their ,,- help and cooperation. Last, but not least, a special thanks to my typist. -

Legacies of the Nuremberg SS-Einsatzgruppen Trial After 70 Years

Loyola of Los Angeles International and Comparative Law Review Volume 39 Number 1 Special Edition: The Nuremberg Laws Article 7 and the Nuremberg Trials Winter 2017 Legacies of the Nuremberg SS-Einsatzgruppen Trial After 70 Years Hilary C. Earl Nipissing University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lmu.edu/ilr Recommended Citation Hilary C. Earl, Legacies of the Nuremberg SS-Einsatzgruppen Trial After 70 Years, 39 Loy. L.A. Int'l & Comp. L. Rev. 95 (2017). Available at: https://digitalcommons.lmu.edu/ilr/vol39/iss1/7 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Law Reviews at Digital Commons @ Loyola Marymount University and Loyola Law School. It has been accepted for inclusion in Loyola of Los Angeles International and Comparative Law Review by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons@Loyola Marymount University and Loyola Law School. For more information, please contact [email protected]. 07 EARL .DOCX (DO NOT DELETE) 1/16/17 4:45 PM Legacies of the Nuremberg SS- Einsatzgruppen Trial after 70 Years HILARY EARL* I. INTRODUCTION War crimes trials are almost commonplace today as the normal course of events that follow modern-day wars and atrocities. In the North Atlantic, we use the liberal legal tradition to redress the harm caused to civilians by the state and its agents during periods of State and inter-State conflict. The truth is, war crimes trials are a recent invention. There were so-called war crimes trials after World War I, but they were not prosecuted with any real conviction or political will. -

The Rights of the Press and the Closed Court Criminal Proceeding G

Nebraska Law Review Volume 57 | Issue 2 Article 9 1978 The Rights of the Press and the Closed Court Criminal Proceeding G. Michael Fenner Creighton University School of Law, [email protected] James L. Koley Creighton University School of Law Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/nlr Recommended Citation G. Michael Fenner and James L. Koley, The Rights of the Press and the Closed Court Criminal Proceeding, 57 Neb. L. Rev. 442 (1978) Available at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/nlr/vol57/iss2/9 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Law, College of at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Nebraska Law Review by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. By G. Michael Fenner* and James L. Koley** The Rights of the Press and the Closed Court Criminal Proceeding ARTICLE OUTLINE I. INTRODUCTION II. PROCEDURAL CONSTITUTIONAL RIGHTS: PROCEDURAL DUE PROCESS A. The Application of Procedural Due Process Rights B. The Scope of the Right 1. "the private interest that will be affected by the official action" 2. "the risk of an erroneous deprivation of such interest through the procedures used, and the probable value, if any, of addi- tional or substitute procedural safeguards" 3. "the government's interest, including the function involved and the fiscal and administrative burdens that the additional or substitute procedural requirement would entail" C. Procedural Due Process: Conclusion III. SUBSTANTIVE CONSTITUTIONAL RIGHTS A. Closed Judicial Proceedings in Criminal Cases as Prior Restraints on News Reporting by the Media 1. -

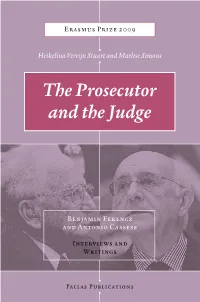

The Prosecutor and the Judge

From Nuremberg and Tokyo Erasmus Prize 2009 to The Hague and Beyond ¶ verrijn stuart | simons Heikelina Verrijn Stuart and Marlise Simons benjamin ferencz, investigator of Nazi war crimes and prosecutor at Nuremberg. Author and lecturer. antonio cassese, first president of the Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia and president of the Special Tribunal for Lebanon. The Prosecutor The prestigious Praemium Erasmianum 2009 was awarded to Benjamin Ferencz and Antonio Cassese, who embody the history of international criminal law from and the Judge Nuremberg to The Hague. The Prosecutor and the Judge is a meeting with these two remarkable men through in depth interviews by Heikelina Verrijn Stuart and Marlise Simons about their judge and the e prosecutor ¶ work and ideas, about the war crimes trials, human cruelty, the self-interest of states; about remorse in the courtroom, about restitution and compensation for th victims and about the strength and the limitations of the international courts. Heikelina Verrijn Stuart is a lawyer and philosopher of law who has published extensively on international humanitarian and criminal law and on remorse, revenge and forgiveness. Since 1993 she has followed the international courts and tribunals for radio and television. Marlise Simons is a correspondent for The New York Times, who has written on conflicts and political murder, torture and disappearances from Latin America. For more than a decade, she has reported on international courts and tribunals in The Hague. Benjamin Ferencz and Antonio Cassese Interviews -

The Eichmann Trial the Eichmann Trial

The Eichmann Trial The Eichmann Trial EUROPEAN JEWRY BEFORE AND AFTER HITLER by SALO W. BARON A HISTORIAN, not an eyewitness or a jurist, I shall concern myself with the historical situation of the Jewish people before, during, and after the Nazi onslaught—the greatest catastrophe in Jewish history, which has known many catastrophes. A historian dealing with more or less contemporary problems con- fronts two major difficulties. The first is that historical perspective usu- ally can be attained only after the passage of time. The second is that much relevant material is hidden away in archives and private collec- tions, which are usually not open for inspection until several decades have passed. In this instance, however, the difficulties have been re- duced. The world has been moving so fast since the end of World War JJ, and the situation of 1961 so little resembles that of the 1930's, that one may consider the events of a quarter of a century ago as belonging almost to a bygone historic era, which the scholarly investigator can view with a modicum of detachment. In fact, a new generation has been growing up which "knew not Hitler." For its part, the older generation is often eager to forget the nightmare of the Nazi era. Hence that period has receded in the consciousness of man as if it had occurred long ago. This article is based on a memorandum that Professor Baron prepared for himself when he was invited to testify at the Eichmann trial, in April 1961, on the Jewish communities destroyed by the Nazis. -

From Weimar to Nuremberg: a Historical Case Study of Twenty-Two Einsatzgruppen Officers

FROM WEIMAR TO NUREMBERG: A HISTORICAL CASE STUDY OF TWENTY-TWO EINSATZGRUPPEN OFFICERS A thesis presented to the faculty of the College of Arts and Sciences of Ohio University In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Master of Arts James L. Taylor November 2006 This thesis entitled FROM WEIMAR TO NUREMBERG: A HISTORICAL CASE STUDY OF TWENTY-TWO EINSATZGRUPPEN OFFICERS by JAMES L. TAYLOR has been approved for the Department of History and the College of Arts and Sciences by Norman J. W. Goda Professor of History Benjamin M. Ogles Dean, College of Arts and Sciences Abstract TAYLOR, JAMES L., M.A., November 2006, Modern European History FROM WEIMAR TO NUREMBERG: A HISTORICAL CASE STUDY OF TWENTY- TWO EINSATZGRUPPEN OFFICERS (134 pp.) Director of Thesis: Norman J. W. Goda This is an examination of the motives of twenty-two perpetrators of the Jewish Holocaust. Each served as an officer of the Einsatzgruppen, mobile killing units which beginning in June 1941, carried out mass executions of Jews in the German-occupied portion of the Soviet Union. Following World War II the subjects of this study were tried before a U.S. Military Tribunal as part of the thirteen Nuremberg Trials, and this study is based on the records of their trial, known as Case IX or more commonly as the Einsatzgruppen Trial. From these records the thesis concludes that the twenty-two men were shaped politically by their experiences during the Weimar Era (1919-1932), and that as perpetrators of the Holocaust their actions were informed primarily by the tenets of Nazism, particularly anti-Semitism. -

Pennsylvania's Appellate Judges, 1969-1994

Duquesne Law Review Volume 33 Number 3 Article 3 1995 Pennsylvania's Appellate Judges, 1969-1994 Jonathan P. Nase Follow this and additional works at: https://dsc.duq.edu/dlr Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation Jonathan P. Nase, Pennsylvania's Appellate Judges, 1969-1994, 33 Duq. L. Rev. 377 (1995). Available at: https://dsc.duq.edu/dlr/vol33/iss3/3 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Duquesne Scholarship Collection. It has been accepted for inclusion in Duquesne Law Review by an authorized editor of Duquesne Scholarship Collection. Duquesne Law Review Volume 33, Spring 1995, Number 3 Pennsylvania's Appellate Judges, 1969-1994 Jonathan P. Nase* TABLE OF CONTENTS I. Introduction .............................. 378 H. Chronology of Judges ....................... 379 A. Supreme Court ........................ 380 1. Members of the Court ................ 380 2. Chief Justices ...................... 388 B. Superior Court ......................... 389 1. Members of the Court ................ 389 2. President Judges ................... 397 C. Commonwealth Court ................... 399 1. Members of the Court ................ 400 2. President Judges ................... 407 III. Statistical Miscellany ....................... 409 A. Methodology ........................... 410 B. All Appellate Judges Serving Between January 1, 1969 and August 1, 1994 ........ 411 1. Party Affiliation .................... 412 2. Race and Gender ................... 415 3. County and Region .................. 418 4. Reason for Leaving the Bench ......... 422 * B.A. American University; J.D. Duke University; Counsel, Legislative Bud- get and Finance Committee, Pennsylvania General Assembly. The opinions expressed herein are solely those of the author and do not represent the opinions of the Com- mittee, its individual members, or its staff. The author would like to thank Mr. Thomas B. -

Joseph Sill Clark Papers

Collection 1958 Joseph Sill Clark Papers 1947-1968 319 boxes, 224 lin. feet Contact: The Historical Society of Pennsylvania 1300 Locust Street, Philadelphia, PA 19107 Phone: (215) 732-6200 FAX: (215) 732-2680 http://www.hsp.org Inventoried by: Katerina Chruma Completed: December 2007 Restrictions: None © 2007 The Historical Society of Pennsylvania. All rights reserved Joseph Sill Clark Papers Collection 1958 Joseph Sill Clark Papers, 1947-1968 Collection 1958 319 boxes, 224 linear feet Creator: Clark, Joseph Sill, 1901-1990 Abstract Joseph Sill Clark was a Democratic reform politician from Philadelphia. Early in his career he served as campaign manager for Richardson Dilworth's mayoral campaign, 1947, and as Philadelphia city controller, 1950-1951. He served as mayor of Philadelphia, 1951-1956, and from 1957 to 1968 he was a United States senator from Pennsylvania. This collection is a partial record of Clark career. It consists primarily of material gathered by staff, reports, memoranda, clippings, news releases, articles, with some correspondence, all on issues and events with which Clark was involved. A small portion of the papers are concerned with Clark's early activities as campaign manager for Richardson Dilworth's mayoral campaign, 1947, and as Philadelphia city controller, 1950-1951, for which there are campaign and office files. Clark's records as mayor of Philadelphia, 1951-1956, include campaign papers, some general office files, and transcripts of speeches. The bulk of material covers Clark's years as United States senator from Pennsylvania, 1957-1968. There are papers for his three senatorial campaigns, 1956, 1962, and especially 1968. His Washington office general file reflects his interest in disarmament, the United Nations, Vietnam, and other matters before and after his appointment to the Senate Foreign Relations Committee in 1965. -

Citators of Pennsylvania*

UNBOUND A Review of Legal History and Rare Books Journal of the Legal History and Rare Books Special Interest Section of the American Association of Law Libraries Volume 11 Number 2 Summer/Fall 2019 UNBOUND A Review of Legal History and Rare Books Unbound: A Review of Legal History and Rare Books (previously published as Unbound: An Annual Review of Legal History and Rare Books) is published by the Legal History and Rare Books Special Interest Section of the American Association of Law Libraries. Articles on legal history and rare books are both welcomed and en- couraged. Contributors need not be members of the Legal History and Rare Books Special Interest Section of the American Associa- tion of Law Libraries. Citation should follow any commonly-used citation guide. Cover Illustration: This depiction of an American Bison, en- graved by David Humphreys, was first published in Hughes Ken- tucky Reports (1803). It was adopted as the symbol of the Legal History and Rare Books Special Interest Section in 2007. BOARD OF EDITORS Mark Podvia, Editor-in-Chief University Librarian West Virginia University College of Law Library 101 Law School Drive, P.O. Box 6130 Morgantown, WV 26506 Phone: (304)293-6786 Email: [email protected] Noelle M. Sinclair, Executive Editor Head of Special Collections The University of Iowa College of Law 328 Boyd Law Building Iowa City, IA 52242 Phone (319)335-9002 [email protected] Kurt X. Metzmeier, Articles Editor Associate Director University of Louisville Law Library Belknap Campus, 2301 S. Third Louisville, KY 40292 Phone (502)852-6082 [email protected] Christine Anne George, Articles Editor Faculty Services Librarian Dr. -

Labor and the Political Leadership of New Deal America

Labor and the Political Leadership of New Deal America DAVID MONTGOMERY Summary: This essay examines the relationship between popular initiatives and government decision-makers during the 1930s. The economic crisis and the reawakening of labor militancy before 1935 elevated men and women, who had been formed by the workers' movement of the 1910s and 1920s, to prominent roles in the making of national industrial policies. Quite different was the reshaping of social insurance and work relief measures. Although those policies represented a governmental response to the distress and protests of the working class, the workers themselves had little influence on their formulation or administration. Through industrial struggles, the Committee for Industrial Organization (CIO) mobilized a new cadre, trained by youthful encounters with urban ethnic life, expanding secondary schooling and subordination to modern corporate management, in an unsuccessful quest for economic planning and universal social insurance through the agency of a reformed Democratic Party. The political and industrial conflicts of the 1930s reshaped both the role of the United States government in economic and social life and the character and influence of the labor movement in ways that formed essential features of the polity for the next forty years. The importance of this transformation made the relationship between government policy decisions and the growing labor movement a subject of intense public controversy at the time, and it has continued to generate disputes among historians to this day. President Franklin D. Roosevelt, while annotating an early edition of his own papers, had depicted the new industrial unions as both a beneficiary of his government and a tribulation to it. -

Nuremberg's Narratives

INTRODUCTION NUREMBERG’S NARRATIVES REVISING THE LEGACY OF THE “SUBSEQUENT TRIALS” Kim C. Priemel and Alexa Stiller R Less than a month after the final verdict of the Nuernberg Military Tri- bunals (NMT)1 had been handed down in the so-called High Command Case, the departing chief prosecutor, Brigadier General Telford Taylor, wound up the four-year-long venture in a statement to the International News Service, articulating his expectations as to the legacy of the trial series. To those who thought that the war crimes proceedings, which by that time had come under scrutiny and criticism on both sides of the Atlantic, would fade into oblivion Taylor issued a stern warning: “I ven- ture to predict that as time goes on we will hear more about Nuremberg rather than less, and that in a very real sense the conclusion of the trials marks the beginning, and not the end, of Nuremberg as a force of poli- tics, law, and morals.”2 Although not everything did go as planned and most of the later Nuremberg trials indeed receded into prolonged obscu- rity, Taylor’s prophecy was not wholly mistaken, and the trials would indeed show a remarkable resilience, if more indirect and implicit than had been intended, in shaping politics, law, and historiography (rather than morals). Tracing these—frequently twisted—roads of the NMT’s influence and impact lies at the heart of the present volume. Taylor’s statement attested to the great ambitions entertained by the American prosecutors in preparing the NMT. The so-called Subse- 2 Kim C. -

The Crusader from Pittsburgh: Michael Musmanno and the Sacco/Vanzetti Case

1 | Page The Crusader from Pittsburgh: Michael Musmanno and the Sacco/Vanzetti Case (Originally titled: To Erase a Stain on this Nation’s Character: Michael Musmanno’s Fight to Vindicate Sacco and Vanzetti) Introduction It is a truism to say that this nation is polarized along ideological lines, with each side retreating into their respective echo chambers, interested only in their version of the truth. Argument ceases in this environment, as each side proclaims its own specific narrative with its own set of facts. While this is unsettling and has been exacerbated by an explosion of media outlets and platforms, this phenomenon is nothing new in our national experience. Other issues have divided America in the past and divided her bitterly. Good cases in point include racial issues, ranging from slavery to civil rights, immigration, and national security, as well as freedom of speech and association. One such case that involved two of these categories was Sacco and Vanzetti: two immigrant Italian anarchists who were arrested, tried, convicted, and eventually executed for a robbery/homicide that took place on the morning of April 15, 1920 in South Braintree, Massachusetts. In many ways, this case stands out as an ideological ink blot test where what you see is determined largely by who and what you are. For conservatives, the two men were dangerous revolutionaries who were part of a larger movement seeking to overthrow the American Government by force and violence. For liberals, they were two philosophical anarchists caught in a Kafkaesque charade that was a direct outgrowth of national hysteria over the Bolshevik revolution.