Chapter \Ve Have Sought to Draw Attention to the Relationship

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Swami Vivekananda

Complete Works of Swami Vivekananda Volume 9 Letters (Fifth Series) Lectures and Discourses Notes of Lectures and Classes Writings: Prose and Poems (Original and Translated) Conversations and Interviews Excerpts from Sister Nivedita's Book Sayings and Utterances Newspaper Reports Complete Works of Swami Vivekananda Volume 9 Letters - Fifth Series I Sir II Sir III Sir IV Balaram Babu V Tulsiram VI Sharat VII Mother VIII Mother IX Mother X Mother XI Mother XII Mother XIII Mother XIV Mother XV Mother XVI Mother XVII Mother XVIII Mother XIX Mother XX Mother XXI Mother XXII Mother XXIII Mother XXIV Mother XXV Mother XXVI Mother XXVII Mother XXVIII Mother XXIX Mother XXX Mother XXXI Mother XXXII Mother XXXIII Mother XXXIV Mother XXXV Mother XXXVI Mother XXXVII Mother XXXVIII Mother XXXIX Mother XL Mrs. Bull XLI Miss Thursby XLII Mother XLIII Mother XLIV Mother XLV Mother XLVI Mother XLVII Miss Thursby XLVIII Adhyapakji XLIX Mother L Mother LI Mother LII Mother LIII Mother LIV Mother LV Friend LVI Mother LVII Mother LVIII Sir LIX Mother LX Doctor LXI Mother— LXII Mother— LXIII Mother LXIV Mother— LXV Mother LXVI Mother— LXVII Friend LXVIII Mrs. G. W. Hale LXIX Christina LXX Mother— LXXI Sister Christine LXXII Isabelle McKindley LXXIII Christina LXXIV Christina LXXV Christina LXXVI Your Highness LXXVII Sir— LXXVIII Christina— LXXIX Mrs. Ole Bull LXXX Sir LXXXI Mrs. Bull LXXXII Mrs. Funkey LXXXIII Mrs. Bull LXXXIV Christina LXXXV Mrs. Bull— LXXXVI Miss Thursby LXXXVII Friend LXXXVIII Christina LXXXIX Mrs. Funkey XC Christina XCI Christina XCII Mrs. Bull— XCIII Sir XCIV Mrs. Bull— XCV Mother— XCVI Sir XCVII Mrs. -

2021 Banerjee Ankita 145189

This electronic thesis or dissertation has been downloaded from the King’s Research Portal at https://kclpure.kcl.ac.uk/portal/ The Santiniketan ashram as Rabindranath Tagore’s politics Banerjee, Ankita Awarding institution: King's College London The copyright of this thesis rests with the author and no quotation from it or information derived from it may be published without proper acknowledgement. END USER LICENCE AGREEMENT Unless another licence is stated on the immediately following page this work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International licence. https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/ You are free to copy, distribute and transmit the work Under the following conditions: Attribution: You must attribute the work in the manner specified by the author (but not in any way that suggests that they endorse you or your use of the work). Non Commercial: You may not use this work for commercial purposes. No Derivative Works - You may not alter, transform, or build upon this work. Any of these conditions can be waived if you receive permission from the author. Your fair dealings and other rights are in no way affected by the above. Take down policy If you believe that this document breaches copyright please contact [email protected] providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. Download date: 24. Sep. 2021 THE SANTINIKETAN ashram As Rabindranath Tagore’s PoliTics Ankita Banerjee King’s College London 2020 This thesis is submitted to King’s College London for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy List of Illustrations Table 1: No of Essays written per year between 1892 and 1936. -

Tanmayee BANERJEE 2014.Pdf

WestminsterResearch http://www.westminster.ac.uk/research/westminsterresearch Nationalism and internationalism in selected Indian English novels: 1909 – 1930 Tanmayee Banerjee School of Social Sciences, Humanities and Languages This is an electronic version of a PhD thesis awarded by the University of Westminster. © The Author, 2014. This is an exact reproduction of the paper copy held by the University of Westminster library. The WestminsterResearch online digital archive at the University of Westminster aims to make the research output of the University available to a wider audience. Copyright and Moral Rights remain with the authors and/or copyright owners. Users are permitted to download and/or print one copy for non-commercial private study or research. Further distribution and any use of material from within this archive for profit-making enterprises or for commercial gain is strictly forbidden. Whilst further distribution of specific materials from within this archive is forbidden, you may freely distribute the URL of WestminsterResearch: (http://westminsterresearch.wmin.ac.uk/). In case of abuse or copyright appearing without permission e-mail [email protected] Nationalism and Internationalism in Selected Indian English Novels: 1909 – 1930 Tanmayee Banerjee A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements of the University of Westminster for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of English School of Social Sciences, Humanities and Languages University of Westminster April 2014 Affirmation Herewith I declare that the work submitted is my own. Appropriate credit has been given to thoughts that were taken directly or indirectly from other sources. -- Tanmayee Banerjee Acknowledgements I owe my sincerest gratitude to all the institutions, organizations and individuals who have been directly and indirectly involved in this project. -

Nandan Gupta. `Prak-Bibar` Parbe Samaresh Basu. Nimai Bandyopadhyay

BOOK DESCRIPTION AUTHOR " Contemporary India ". Nandan Gupta. `Prak-Bibar` Parbe Samaresh Basu. Nimai Bandyopadhyay. 100 Great Lives. John Cannong. 100 Most important Indians Today. Sterling Special. 100 Most Important Indians Today. Sterling Special. 1787 The Grand Convention. Clinton Rossiter. 1952 Act of Provident Fund as Amended on 16th November 1995. Government of India. 1993 Vienna Declaration and Programme of Action. Indian Institute of Human Rights. 19e May ebong Assame Bangaliar Ostiter Sonkot. Bijit kumar Bhattacharjee. 19-er Basha Sohidera. Dilip kanti Laskar. 20 Tales From Shakespeare. Charles & Mary Lamb. 25 ways to Motivate People. Steve Chandler and Scott Richardson. 42-er Bharat Chara Andolane Srihatta-Cacharer abodan. Debashish Roy. 71 Judhe Pakisthan, Bharat O Bangaladesh. Deb Dullal Bangopadhyay. A Book of Education for Beginners. Bhatia and Bhatia. A River Sutra. Gita Mehta. A study of the philosophy of vivekananda. Tapash Shankar Dutta. A advaita concept of falsity-a critical study. Nirod Baron Chakravarty. A B C of Human Rights. Indian Institute of Human Rights. A Basic Grammar Of Moden Hindi. ----- A Book of English Essays. W E Williams. A Book of English Prose and Poetry. Macmillan India Ltd.. A book of English prose and poetry. Dutta & Bhattacharjee. A brief introduction to psychology. Clifford T Morgan. A bureaucrat`s diary. Prakash Krishen. A century of government and politics in North East India. V V Rao and Niru Hazarika. A Companion To Ethics. Peter Singer. A Companion to Indian Fiction in E nglish. Pier Paolo Piciucco. A Comparative Approach to American History. C Vann Woodward. A comparative study of Religion : A sufi and a Sanatani ( Ramakrishana). -

Remembering Sister Nivedita, the Irish Woman Who Devoted Herself Fully to the Cause of India (In the Late 1800'S)

Sister Nivedita Remembering Sister Nivedita, the Irish woman who devoted herself fully to the cause of India (in the late 1800's) Sister Nivedita, born Margaret Elizabeth Noble, is regarded as one of the great women of India for dedicating her life to the cause of India and Hinduism. Interestingly, she was born in the Western world but made her mark in India. Popularly known as Sister Nivedita, she was born on October 28, 1867, in Dungannon, Northern Ireland. Born as Margaret Elizabeth Noble, she was more popularly known as sister Nivedita. She was an Anglo-Irish social worker, who was one amongst the many disciples of Swami Vivekananda. She came across Swami Vivekananda in the year 1895 in London. It was the Swami, who called her by the name "Nivedita". The word Nivedita is used to refer to someone who is highly dedicated to the almighty God. Well, in this article, we will present you with the biography of Sister Nivedita, who has made a niche for herself in the arena of spirituality. Sister Nivedita met Swami Vivekananda in 1895 in London and travelled to Calcutta in 1898. Vivekananda initiated her into the vow of Brahmacharya on March 25, 1898. Swamiji wanted that under her care, the women of India specially in Calcutta be looked after to improve upon their health and education. She kept her Guru's wishes. One of Swami Vivekananda's closest disciples, was converted to Hinduism by Swami Vivekananda with a new name as Sister Nivedita meaning "the offered one". To introduce Sister Nivedita to the local people, in his speech Swami Vivekananda said – "England has sent us another gift in Miss Margaret Noble." Early Life She came into this world on October 28, 1867. -

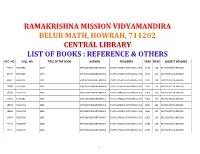

Ramakrishna Mission Vidyamandira Belur Math, Howrah, 711202 Central Library List of Books : Reference & Others Acc

RAMAKRISHNA MISSION VIDYAMANDIRA BELUR MATH, HOWRAH, 711202 CENTRAL LIBRARY LIST OF BOOKS : REFERENCE & OTHERS ACC. NO. CALL. NO. TITLE OF THE BOOK AUTHOR PUBLISHER YEAR PRICE SUBJECT HEADING 44638 R032/ENC 1978 ENYCOLPAEDIA BRITANNICA ENCYCLOPAEDIA BRITANNICA, ING 1978 150 ENCYCLOPEDIA-ENGLISH 44639 R032/ENC 1979 ENYCOLPAEDIA BRITANNICA ENCYCLOPAEDIA BRITANNICA, ING 1979 100 ENCYCLOPEDIA-ENGLISH 44641 R-032/BRI 1981 ENYCOLPAEDIA BRITANNICA ENCYCLOPEADIA BRITANNICA, INC 1981 100 ENCYCLOPEDIA-ENGLISH 15648 R-032/BRI 1982 ENYCOLPAEDIA BRITANNICA ENCYCLOPAEDIA BRITANNICA, ING 1982 100 ENCYCLOPEDIA-ENGLISH 15649 R-032/ENC 1983 ENYCOLPAEDIA BRITANNICA ENCYCLOPAEDIA BRITANNICA, ING 1983 100 ENCYCLOPEDIA-ENGLISH 17913 R032/ENC 1984 ENYCOLPAEDIA BRITANNICA ENCYCLOPAEDIA BRITANNICA, ING 1984 350 ENCYCLOPEDIA-ENGLISH 18648 R-032/ENC 1985 ENYCOLPAEDIA BRITANNICA ENCYCLOPAEDIA BRITANNICA, ING 1985 100 ENCYCLOPEDIA-ENGLISH 18786 R-032/ENC 1986 ENYCOLPAEDIA BRITANNICA ENCYCLOPAEDIA BRITANNICA, ING 1986 100 ENCYCLOPEDIA-ENGLISH 19693 R-032/ENC 1987 ENYCOLPAEDIA BRITANNICA ENCYCLOPEADIA BRITANNICA, INC 1987 100 ENCYCLOPEDIA-ENGLISH 21140 R-032/ENC 1988 ENYCOLPAEDIA BRITANNICA ENCYCLOPEADIA BRITANNICA, INC 1988 100 ENCYCLOPEDIA-ENGLISH 21141 R-032/ENC 1989 ENYCOLPAEDIA BRITANNICA ENCYCLOPEADIA BRITANNICA, INC 1989 100 ENCYCLOPEDIA-ENGLISH 1 ACC. NO. CALL. NO. TITLE OF THE BOOK AUTHOR PUBLISHER YEAR PRICE SUBJECT HEADING 21426 R-032/ENC 1990 ENYCOLPAEDIA BRITANNICA ENCYCLOPAEDIA BRITANNICA, ING 1990 150 ENCYCLOPEDIA-ENGLISH 21797 R-032/ENC 1991 ENYCOLPAEDIA -

Publication Book List

The Ramakrishna Mission Institute of Culture (A branch centre of Ramakrishna Mission, P.O. Belur Math, Dist. Howrah, West Bengal - 711202) PHONE : (91-33-) 2464-1303 (3 LINES) ; 2465-2531 (2 LINES); 2466-1235 (3 LINES); FAX : (91-33-) 2464-1307 E.Mail : [email protected] ; [email protected]; Website : www.sriramakrishna.org Mail to : The Ramakrishna Mission Institute of Culture, Gol Park, Kolkata 700 029 BOOK LIST (INSTITUTE’S PUBLICATION) : ORDER FORM AS ON JANUARY 2019 Books on Sri Ramakrishna Order Name of books Author’s/Editor’s Name Pages Price copies A Portrait of Sri Ramakrishna Editor : A. Salm, S. Dhar & P. De 928 500.00 The Way to God Swami Lokeswarananda 482 290.00 Sri Ramakrishna : A Prophet for the New Age Richard Schiffman 256 100.00 Ramakrishna and Christ Hans Torwesten 240 80.00 Great Thinkers on Ramakrishna-Vivekananda Ed. : Swami Lokeswarananda 224 100.00 Benoy Sarkar and Ramakrishna-Vivekananda Movement Haridas Mukherjee 50 20.00 Sri Ramakrishna : the Symbol of Harmony of Religions Hossainur Rahman 52 15.00 Sri Ramakrishna in the Eyes of Brahmo & Christian Admirers Pub : Swami Sarvabhutananda 164 60.00 Leo Tolstoy and Sri Ramakrishna Serigei D. Serebriany 44 12.00 Ramakrishna’s Religion R. K. DasGupta 135 40.00 Vedanta and Ramakrishna Swami Swahananda 456 150.00 Sri Ramakrishna and Spiritual Renaissance Swami Nirvedananda 288 120.00 Sri Ramakrishna : Myriad Facets Pub : Swami Sarvabhutananda 440 150.00 Some Inspiring Illustrations of Sri Ramakrishna, Holy Mother & Swamiji and Their Love Swami Tathagatananda 172 -

VIDYASAGAR UNIVERSITY Philosophy

VIDYASAGAR UNIVERSITY Curriculum for 3-Year B. A (HONOURS) in Philosophy Under Choice Based Credit System (CBCS) w.e.f 2018-2019 1 Downloaded from Vidyasagar University by 157.43.212.40 on 14 August 2020 : 15:30:09; Copyright : Vidyasagar University http://www.vidyasagar.ac.in/Downloads/ShowPdf.aspx?file=/UG_Syllabus_CBCS_FULL/BA_HONS/philosophy_hons.pdf VIDYASAGAR UNIVERSITY BA (Honours) in Philosophy [Choice Based Credit System] Yea Semester Course Course Course Title Credit L-T-P Marks r Type Code CA ESE TOTAL Semester-I 1 I Core-1 C1T: Indian Philosophy -I 6 5-1-0 15 60 75 Core-2 C2T: History of Western Philosophy - I 6 5-1-0 15 60 75 GE-1 TBD 6 5-1-0 15 60 75 AECC-1 English/MIL 2 1-1-0 10 40 50 (Elective) Semester –I: total 20 275 Semester-II II Core-3 C3T: Indian Philosophy - II 6 5-1-0 15 60 75 Core-4 C4T: History of Western Philosophy - II 6 5-1-0 15 60 75 GE-2 TBD 6 5-1-0 15 60 75 AECC-2 ENVS 4 20 80 100 (Elective) Semester-II : total 22 325 2 Downloaded from Vidyasagar University by 157.43.212.40 on 14 August 2020 : 15:30:09; Copyright : Vidyasagar University http://www.vidyasagar.ac.in/Downloads/ShowPdf.aspx?file=/UG_Syllabus_CBCS_FULL/BA_HONS/philosophy_hons.pdf Yea Semester Course Course Course Title Credit L-T-P Marks r Type Code CA ESE TOTAL Semester-III 2 III Core-5 C5T: Philosophy of Mind 6 5-1-0 15 60 75 Core-6 C6T: Social and Political Philosophy 6 5-1-0 15 60 75 Core-7 C7T: Philosophy of Religion 6 5-1-0 15 60 75 GE-3 TBD 6 5-1-0 15 60 75 SEC-1 SEC-1:Computer Application Or SEC-1: Philosophy of 2 1-1-0 10 40 50 Human -

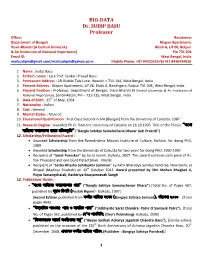

BIO-DATA Dr. SUDIP BASU Professor

BIO-DATA Dr. SUDIP BASU Professor Office: Residence: Department of Bengali Alapan Apartments Visva-Bharati (A Central University Block A, UF 06, Bolpur & An Institution of National Importance) Pin 731 204 Email ID: West Bengal, India [email protected]/[email protected] Mobile Phone: +91 9432352578/+91 8436434930 1. Name : Sudip Basu 2. Father’s name : Late Prof. Sankari Prasad Basu 3. Permanent Address : 1B Olabibi Tala Lane, Howrah – 711-104, West Bengal, India 4. Present Address : Alapan Apartments, UF 06, Block A, Bandhgora, Bolpur 731 204, West Bengal, India 5. Present Position : Professor, Department of Bengali, Visva-Bharati (A Central University & An Institution of National Importance), Santiniketan, Pin – 731-235, West Bengal, India 6. Date of Birth : 15th of May, 1964 7. Nationality : Indian 8. Cast : General 9. Marital Status : Married 10. Educational Qualification : First Class Second in MA (Bengali) from the University of Calcutta, 1987 11. Research Degree : Awarded Ph.D. from the University of Calcutta on 26.10.1995. Title of the Thesis: “বা廬লা সাহি重যে সমা重লাচনা ধারার গহযপ্র嗃হয” (“Bangla Sahitye Samalochana Dharar Gati Prakriti”) 12. Scholarship/Fellowship/Award : Awarded Scholarship from the Ramakrishna Mission Institute of Culture, Kolkata, for doing PhD, 1989 Awarded Scholarship from the University of Calcutta for two years for doing PhD, 1990-1992 Recipient of “Sarat Puraskar” by Sarat Samiti, Kolkata, 2007. This award contains cash prize of Rs. Ten Thousand and one Gold Plated Silver Medal Recipient of “Sarba-Bhasha Sahityakar Samman” by Akhil Bharatiya Sahitya Parishad, New Delhi, at Bhopal (Madhya Pradesh) on 19th October 2012. -

Monthly Programme: November 2019

Price : Rs. 2/- The Ramakrishna Mission Institute of Culture Gol Park, Kolkata - 700 029 PHONE : (91-33-) 2464-1303 (3 LINES) ; 2465-2531 (2 LINES); 4030-1200 FAX : (91-33-) 2464-1307; E.Mail : [email protected] Website : www.sriramakrishna.org MONTHLY PROGRAMMES FOR JULY 2019 Shrine : Devotional Songs : In the Shrine from 5.00 p.m. to 5.50 p.m. every working day 1 Monday, 5.30 p.m. Durga Subject : Adarsha Charitra Majumdar Endowment Lecture Mahabir Hanuman (Bengali) Subject : Vedantasara (Bengali) Speaker : Sri Swapan Banerjee, Formerly Teacher, Ramakrishna Speaker : Dr Sitanath Goswami, Mission Vidyapith, Purulia Formerly Professor of Sanskrit, Jadavpur University Venue : Vivekananda Hall Venue : Shivananda Hall 4 Thursday, 6.00 p.m. R. K. Bhuwalka Memorial Lecture 2 Tuesday, 6.00 p.m. Subject: Bhagavat Katha (Bengali) Subrata Basu Memorial Lecture Speaker : Prof. Ayan Bhattacharya, Subject: Brahma Sutra (Bengali) Head of the Dept. of Sanskrit, West Speaker : Dr Samiran Chandra Bengal State Univertsity, Barasat Chakrabarti, Formerly Director, Venue : Shivananda Hall School of Vedic Studies, Rabindra Bharati University 5 Friday, 6.00 p.m. : Swami Book Release : ‘Brahmasutramrita’ Dayananda Memorial Lecture authored by Smt. Sumitra Mitra (Ghosh) Subject : Adhyatma Ramayana Venue : Vivekananda Hall (Sanskrit) Speaker : Swami Tattwavidananda, 3 Wednesday, 6.00 p.m. Assistant General Secretary, Prof. Sankari Prasad Basu Ramakrishna Math and Ramakrishna Memorial Lecture Mission , Belur Math Venue : Shivananda Hall Speaker : Dr. Sumitra Mitra (Ghosh) Formerly Head of the Department of History, Vidyasagar College for 6 Saturday, 4.00 p.m. Women Vivekananda Anusheelan (Personality Venue : Shivananda Hall Development Programme for Youth members) 6 Saturday, 6.00 p.m. -

19 Bulletin :: Seva Yoga :: Swami Suparnananda

SEVâ-YOGA—CULMINATION OF ALL PHILOSOPHIES Sevà-Yoga—Culmination of All Philosophies SWAMI SUPARNANANDA dvaita Vedanta has given us a Advaita. This is Sevà-Yoga which is an unique philosophy which culminates antithesis to Shankara’s Advaita, Madhva’s Ain the realization that ‘I am All and Dvaita and Ràmànuja’s Vishishtàdvaita. It All in Me’, ie ‘Oneness of Existence’ which accepts the falsity of the world but does not has been encapsulated in the Upanishadic stay away from serving it. It has been made utterances like ‘Aham brahmàsmi’ or the means of attaining the full knowledge of ‘Sarvam khalvidam brahma’. the Màyàvàda and see Brahman in all. This Everybody used to criticize Advaita important discipline of sevà was lacking in philosophy as being highly abstract. Among the Upanishads and in all their this ‘everybody’ were the Western interpretations. Swamiji thus made the philosophers like Hegel, Kant and the Eastern Advaita philosophy poetic and pragmatic— philosophers and saints like Raja Rammohun as pragmatic as the Western philosophies, Roy, Iswar Chandra Vidyasagar, all Dvaitins yet it embraces the entire world out of love. and Vishishtàdvaitins such as Madhvàchàrya Also, Swamiji has left Kant and Hegel and Ràmànuja including the Vaishnavas. One far behind and brought a unique synthesis can easily add Buddha’s name to the list. among the philosophies, on one hand, and Swami Vivekananda here has a pivotal among the Avatàras like Sri Krishna, role to play. He is the culmination of Buddha and Shankara, on the other. Krishna, Buddha and Shankara—the three In Buddha’s preachings, cessation of giants in the domain of human thoughts. -

Draft-Philosophy-26-4-18.Pdf

1 University of Calcutta Draft BA (Honours)-CBCS Syllabus in Philosophy, 2018 A. Core Courses [Fourteen courses; Each course: 6 credits (5 theoretical segment+ 1 for tutorial-related segment). Total: 84 credits • Each course carries 80 marks and Minimum 80 classes. • 65 marks for theoretical segment: 50 marks for subjective/descriptive questions + 15 marks for 1 mark questions. • Question Pattern for subjective/descriptive segment of 50 marks: 2 questions (within 100 words; one from each module) out of 4 (10 x2 = 20) + 2 questions (within 500 words; one from each module) out of 4(15 x 2 = 30). • 15 marks for tutorial-related segments as suggested below (any one from each mode): Any one of the following modes: upto 1000 words for one Term Paper/upto 500 words for each of the two Term Papers/ equivalent Book Review/equivalent Comprehension/equivalent Quotation or Excerpt Elaboration. Report Presentation/Poster Presentation/Field work--- based on syllabus- related and/or current topics (May be done in groups) [The modes and themes and/or topics are be decided by the concerned faculty of respective colleges.] • Core courses: 2 each in Semesters 1 and 2; Three each in Semesters 3 and 4; 2 each in Semesters 5 and 6. IMPORTANT NOTES: • Cited advanced texts in Bengali are not necessarily substitutes, but supplementary to the English books. • The format is subject to the common structural CBCS format of the University. Semester 1 CC(H) 1- Indian philosophy - I CC(H) 2- History of western Philosophy - I Semester 2 CC (H)3 Indian philosophy - II