Climbing the Cerulean Butte

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

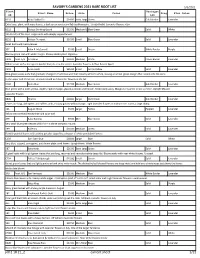

SAVORY's GARDENS 2021 BARE ROOT LIST Pdf 2 18 21 Test Sheet3

SAVORY'S GARDENS 2021 BARE ROOT LIST 2/28/2021 Plant Variegat Plant Name Price Size Color Frag Flwr Color ID ion B210 Abba Dabba Do $14.00 Extra LargeGreen Gold Border Lavender Extra large plant with wavy leaves, a dark-green center and light gold margins. Upright habit. Lavender flowers.</p> B122 Abiqua Drinking Gourd $13.50 Medium/LargeBlue-Green Solid White 2014 Hosta of the Year. Large hosta with deeply cupped leaves. B216 Abiqua Trumpet $10.00 Small Blue-Green Solid Lavender Small hosta with heavy leaves. 337 Allan P. McConnell $5.00 Small Green White Border Purple Narrow green leaf with white margin. Showy border plant. Vigorous. C302 Avail. 6/1 Amazone $18.00 Medium White Green Border Lavender White leaves with a dark green border that jets into the center. lavender flowers. A 'Paul Revere Sport' C303 Anna Lindh $25.00 Small Grn to Yellow Solid Lavender Blue-green leaves early that gradually change to chartreuse and then creamy-white to white, leaving a narrow green margin that bleeds into the veins in the upper end of the leaf. A small mound with lavender flowers in the fall. C194 Änna Mae $17.00 Medium Blue-Green Gold Border Lavender Blue-green with a wide, yellow, slightly rippled margin, glaucous bloom underneath. Moderately wavy. Margin turns white in late summer. Upright Mound Lavender flowers B890 Atlantis $18.00 Large Dark Green Gold Border Lavender Leaves are long, dark-green and ruffled, with a showy golden-yellow margin. Light lavender flowers in midsummer. Forms a large clump. 121 August Moon $5.00 Large Yellow Rippled Lavender Yellow with crinkled leaves that hold color well. -

The Early History of Glaucoma: the Glaucous Eye (800 BC to 1050 AD)

Journal name: Clinical Ophthalmology Article Designation: Review Year: 2015 Volume: 9 Clinical Ophthalmology Dovepress Running head verso: Leffler et al Running head recto: Early history of glaucoma open access to scientific and medical research DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.2147/OPTH.S77471 Open Access Full Text Article REVIEW The early history of glaucoma: the glaucous eye (800 BC to 1050 AD) Christopher T Leffler1 Abstract: To the ancient Greeks, glaukos occasionally described diseased eyes, but more Stephen G Schwartz2 typically described healthy irides, which were glaucous (light blue, gray, or green). During Tamer M Hadi3 the Hippocratic period, a pathologic glaukos pupil indicated a media opacity that was not Ali Salman1 dark. Although not emphasized by present-day ophthalmologists, the pupil in acute angle clo- Vivek Vasuki1 sure may appear somewhat green, as the mid-dilated pupil exposes the cataractous lens. The ancient Greeks would probably have described a (normal) green iris or (diseased) green pupil 1Department of Ophthalmology, as glaukos. During the early Common Era, eye pain, a glaucous hue, pupil irregularities, and Virginia Commonwealth University, Richmond, VA, USA; 2Bascom Palmer absence of light perception indicated a poor prognosis with couching. Galen associated the Eye Institute, University of Miami glaucous hue with a large, anterior, or hard crystalline lens. Medieval Arabic authors translated Miller School of Medicine, Naples, FL, USA; 3Graduate School of Medicine, glaukos as zarqaa, which also commonly described light irides. Ibn Sina (otherwise known as University of Tennessee Medical Avicenna) wrote that the zarqaa hue could occur due to anterior prominence of the lens and Center at Knoxville, TN, USA For personal use only. -

Japan Blues: Ao, Ai, Midori, Aizome, Ao-Ja-Shin. in Harkness, R

CLARKE, J. 2017. Japan blues: ao, ai, midori, aizome, ao-ja-shin. In Harkness, R. (ed.) An unfinished compendium of materials. Aberdeen: University of Aberdeen [online], pages 85-88. Available from: https://knowingfromtheinside.org/files/unfinished.pdf Japan blues: ao, ai, midori, aizome, ao-ja-shin. CLARKE, J. 2017 This document was downloaded from https://openair.rgu.ac.uk IRON ORE JAPAN BLUES interchangeable. Ao is a good example; in Jan Peter Laurens Loovers Ao, Ai, Midori, Aizome, Ao-ja-shin Japan, ao is the colour of grass and leaves, Jen Clarke and traffic lights and the colour of the sky. … but folk in the housen, as the People of the It can be blue and green, or blue or green. It Hills call them, must be ruled by Cold Iron. These impressions of blue have come from can also be an-almost black, if it is a horse’s Folk in housen are born on the near side reflecting on visitors responses to my use of coat, or be used to imply something pale, of Cold Iron – there’s iron in every man’s the colour blue during a residency in Japan green, unripe, unready, unpalatable. The house, isn’t there? They handle Cold Iron that focussed on making and exhibiting 24 boundaries are not the same, but more than every day of their lives, and their fortune’s 24-hour cyanotype photograms. The exhibi- this, to think about blue in Japan, I also made or spoilt by Cold Iron in some shape or tion was arranged as an act of remembrance, think of green. -

A Fall Sampler: Salvia, Corydalis, Ceratostigma

AFALL SAMPLER Five experts pick their favorite plant for autumn display. Salvia ‘Indigo Spires’ though it begins to bloom in late spring or early summer, Salvia ‘Indigo Spires’ surges to a crescen- do of unruly flamboyance in fall. Like Medusa’s ser- pentine tresses, its curiously contorted, foot-long floral spikes, composed of tightly packed whorls of small, iri- descent, violet-blue blossoms, coil about in all direc- tions and, bouncing with bumblebees, seem to take on a life of their own. The striking color works with strong, hot oranges and golds, such as Cosmos ‘Bright Salvia Lights’, and with calmer, cooler pinks, light yellow, or ‘Indigo silver as well. Spires’ A sterile hybrid thought to be a cross between S. fari- LIGHT: Full sun nacea and S. longispicata, Salvia ‘Indigo Spires’ quickly SOIL: Moderately forms a stiff, open shrub, four feet high and wide, with moist, humus-rich, soft, faintly fuzzy, musky, medium green leaves. well draining soil. Root-hardy in USDA Zones 7b to 10, it can be HARDINESS: treated as an annual elsewhere. USDA Zones This elegant if eccentric creature enjoys full 7b–10 sun in well-drained, moderately moist, humus- rich soil. A loose mulch conserves moisture in summer and insulates the roots in winter (where it’s hardy). An occasional light pruning encourages a fuller shape and more flowers. Salvia ‘Indigo Spires’ is a hit with but- terflies and hummingbirds, too. —Carol Bishop Miller Corydalis lutea all the best flowers are yellow, and of all the yellows my favorite is Corydalis lutea. The word corydalis is Greek for crested lark—a reference to the flowers’ shape—but yellow corydalis is the only common name I can track down. -

The Inheritance of Some Plant Colors in Cabbage'

THE INHERITANCE OF SOME PLANT COLORS IN CABBAGE' By ROY MAGRUDEíI,^ formerly assistant horticulturist, Ohio Agricultural Experi- ment Station, and C. H. MYERS, professor, Department of Plant Breeding, New York (Cornell) Agricultural Experiment Station INTRODUCTION Until recently, only two genetic colors of Brassica were recognized, red or purple, and green. In 1924 Kristofferson called attention to a type with colored midribs which probably is the same as the type herein described as sun color. The appearance of a previously unde- scribed color type called magenta, in the cultures of the junior author immediately aroused mterest in its genetic relationship to the pre- viously described color types. The purpose of this paper is to report the results of investigations on the genetic relationships between color types which have been designated as purple, magenta, sun color, and green. REVIEW OF LITERATURE As early as 1928 Wiegmann {9)^ reported that red color in cabbage was incompletely dominant over green. E. P. F. Sutton (5), Pease (5), and Allgay er {1) also reported incomplete dominance in the Fi and concluded that only a single factor was involved in the production of the red color. In a later paper Pease {6), from his study of a blue kohlrabi X green savoy cabbage cross, concluded that the purple of blue Vienna kohlrabi was due to two complementary factors. Moldenhawer (4) obtained similar results from a purple kohlrabi X green brussels sprouts cross. A. W. Sutton (7) reports plants with purple foliage in the F2 of Drumhead cabbage X kohlrabi and Drftmhead cabbage X thousand- headed kale crosses, although no mention was made of color on the Fi or on either of the parents. -

Schodack Birding Checklist

Species Sp Su F W Species Sp Su F W SHRIKES & VIREOS WOOD-WARBLERS (cont.) Northern Shrike R Black-throated Blue Warbler C C BIRDS Yellow-throated Vireo C C Black-throated Green Warbler C C Red-eyed Vireo C C Blackburnian Warbler U U OF Warbling Vireo C C Prothonotary Warbler U U Blue-headed Vireo C C Black-and-white Warbler C C JAYS & CROWS Mourning Warbler U U SCHODACK ISLAND Blue Jay A A A A Cerulean Warbler*# U U American Crow* A A A A Canada Warbler U U STATE PARK Fish Crow O O O American Redstart* C C 1 Schodack Landing Way SWALLOWS Common Yellowthroat C C Schodack Landing, NY 12156 Purple Martin U C Pine Warbler U U (518) 732-0187 Tree Swallow* U C Prairie Warbler U C Barn Swallow* U C Blackpoll Warbler U U Bank Swallow* U C Hooded Warbler U C CHICKADEES, TITMICE & NUTHATCHES Yellow-throated Warbler O O Black-capped Chickadee A A A A SPARROWS Tufted Titmouse C C C C Eastern Towhee C C White-breasted Nuthatch C C C C Field Sparrow C C CREEPERS, WRENS & KINGLETS Song Sparrow* C A C C Brown Creeper U U U U Swamp Sparrow C C House Wren* U C American Tree Sparrow C C C C Carolina Wren C C C C Chipping Sparrow* C C Marsh Wren U C U Savannah Sparrow C C Ruby-crowned Kinglet U U White-throated Sparrow C U U U Golden-crowned Kinglet U U White-crowned Sparrow U U Blue-gray Gnatcacther C Dark-eyed Junco C C C C Cerulean Warbler THRUSHES, MIMICS, STARLINGS & WAXWINGS CARDINALS American Robin* A C C O Northern Cardinal* A A A A Located on a peninsula in the northern region of Eastern Bluebird* A A C O Scarlet Tanager U C the Hudson River Estuary system, Schodack Island Veery* A C U Rose-breasted Grosbeak* U C State Park’s 864-acre Bird Conservation Area is Wood Thrush* A C U Indigo Bunting U C critical breeding habitat for many species, including Hermit Thrush C C U ORIOLES & BLACKBIRDS species of special concern such as Cerulean Warblers. -

Container Brochure 2015.Psd

Warm Weather Containers 2015 – The Scott Arboretum Container gardening has attained growing popularity as it is ideal for gardeners who may not have the time, space, or economic means to garden on a large scale. Containers need not be restricted to traditional terra cotta or plastic, but can be anything sizable, durable, and fashioned out of various materials, such as metal or wood. Our examples are intended to inform and inspire anyone to indulge in container gardening. Each container at the Scott Arboretum has a numbered stake corresponding to the number found within this brochure. For each numbered container, the plants are listed with a short description allowing visitors to pinpoint specific plants. Containers designed and planted by Josh Coceano and John Bickel. Wister Center: 1. Alcantarea odorata – silver, pineapple-like foliage bromeliad Fuchsia ‘Hidcote Beauty’ – salmon-pink corolla with creamy white sepals, cascading Fuchsia magellanica ‘Riccartonii’ – dark green leaves; floriferous, with pendulous Fuchsia-colored sepals and reproductive structures with true purple petals Pellionia pulchra – (Satin pellionia) unique trailing plant, matte gray-green leaves with dark silver veins, purple undersides and brownish-red stems Pilea glauca ‘Aquamarine’ – small, matte green-silver leaves growing on fleshy red-purple stems Peperomia griseo-argentea – (Ivy-leaf peperomia) Silver and gray, puckered, heart-shaped leaves with long cream spikes of inconspicuous flowers 2. Alcantarea odorata – silver, pineapple-like foliage bromeliad Fuchsia -

SPECIES IDENTIFICATION GUIDE National Plant Monitoring Scheme SPECIES IDENTIFICATION GUIDE

National Plant Monitoring Scheme SPECIES IDENTIFICATION GUIDE National Plant Monitoring Scheme SPECIES IDENTIFICATION GUIDE Contents White / Cream ................................ 2 Grasses ...................................... 130 Yellow ..........................................33 Rushes ....................................... 138 Red .............................................63 Sedges ....................................... 140 Pink ............................................66 Shrubs / Trees .............................. 148 Blue / Purple .................................83 Wood-rushes ................................ 154 Green / Brown ............................. 106 Indexes Aquatics ..................................... 118 Common name ............................. 155 Clubmosses ................................. 124 Scientific name ............................. 160 Ferns / Horsetails .......................... 125 Appendix .................................... 165 Key Traffic light system WF symbol R A G Species with the symbol G are For those recording at the generally easier to identify; Wildflower Level only. species with the symbol A may be harder to identify and additional information is provided, particularly on illustrations, to support you. Those with the symbol R may be confused with other species. In this instance distinguishing features are provided. Introduction This guide has been produced to help you identify the plants we would like you to record for the National Plant Monitoring Scheme. There is an index at -

KANSAS ORNITHOLOGICAL SOCIETY NEWSLETTER Division

KANSAS ORNITHOLOGICAL SOCIETY NEWSLETTER Division of Biology, Kansas State University Volume 6, No. 3 Manhattan, KS 66506 July 1979 TEN BEST BIRDS OF THE YEAR (May 1978-April 1979) Marvin D. Schwilling Information used in choosing the top ten included the "best birds" reports plus a search of the Bulletin, Newsletter, Christmas Counts as well as in the "Unusual bird report cards", which was a new source this year. Consideration was given to previous state records or specimens, geographic location in the state, season of sighting, nesting, etc. as well as personel judgment. Contestants were: from "Best Birds" report forms: 1. Cape May Warbler 7. Chestnut-collareg Longspur 2. Common Redpoll 8. Golden Eagle 3. Audubon's Warbler 9. Bald Eagle 4. Mississippi Kite 10. Least Bittern 5. Connecticut Warbler 11. Broad-tailed Hummingbird 6. Golden-winged Warbler from "Unusual ~ird"report cards : 12. Olivaceous Cormorant 16. Lazuli Bunting 13. White-throated Swift 17. Woodcock (Nesting) 14. Green-tailed Towhee 18. Golden-winged Warbler 15. Mexican Jay from Bulletin, Newsletter, Correspondence and Telephone: 19. Black Rail 27. Steller's Jay 20. Black-necked Stilt (nesting)28. Scrub Jay 21. Hooded Warbler 29. Glaucous Gull 22. Cerulean Warbler 30. Sharp-tailed Sandpiper 23. Brewer's Sparrow 31. Mountain Chickadee 24. Willet (June 28) 32. Louisiana Waterthrush (nesting Lyon Co.) 25. Canada Warbler 33. Curve-billed Thrasher (nesting) 26. Black- throated Green 34. Red Bobwhite Warbler (Nov. 4) HONORABLE MENTION 1. Green-tailed Towhee - May 7, 8, 9, 10 Barton County, Laurel Dirks 2. Cerulean Warbler - May 17, Morton County, Marvin Schwilling 3. -

SAVORY's GARDENS 2021 BARE ROOT LIST Pdf 2 18 21 2 Current

SAVORY'S GARDENS 2021 BARE ROOT LIST 5/5/2021 Plant Variegat Plant Name Price Size Color Frag Flwr Color ID ion B210 Abba Dabba Do $14.00 Extra LargeGreen Gold Border Lavender Extra large plant with wavy leaves, a dark-green center and light gold margins. Upright habit. Lavender flowers.</p> B122 Abiqua Drinking Gourd $13.50 Medium/LargeBlue-Green Solid White 2014 Hosta of the Year. Large hosta with deeply cupped leaves. B216 Abiqua Trumpet $10.00 Small Blue-Green Solid Lavender Small hosta with heavy leaves. 337 Allan P. McConnell $5.00 Small Green White Border Purple Narrow green leaf with white margin. Showy border plant. Vigorous. C302 Avail. 6/1 Amazone $18.00 Medium White Green Border Lavender White leaves with a dark green border that jets into the center. lavender flowers. A 'Paul Revere Sport' C303 Anna Lindh $25.00 Small Grn to Yellow Solid Lavender Blue-green leaves early that gradually change to chartreuse and then creamy-white to white, leaving a narrow green margin that bleeds into the veins in the upper end of the leaf. A small mound with lavender flowers in the fall. C194 Änna Mae $17.00 Medium Blue-Green Gold Border Lavender Blue-green with a wide, yellow, slightly rippled margin, glaucous bloom underneath. Moderately wavy. Margin turns white in late summer. Upright Mound Lavender flowers B890 Atlantis $18.00 Large Dark Green Gold Border Lavender Leaves are long, dark-green and ruffled, with a showy golden-yellow margin. Light lavender flowers in midsummer. Forms a large clump. 121 August Moon $5.00 Large Yellow Rippled Lavender Yellow with crinkled leaves that hold color well. -

Swatch Name HLS RGB HEX Absolute Zero 217° 36% 100% 0 72

Swatch Name HLS RGB HEX Absolute Zero 217° 36% 100% 0 72 186 #0048BA Acid green 65° 43% 76% 176 191 26 #B0BF1A Aero 206° 70% 70% 124 185 232 #7CB9E8 Aero blue 151° 89% 100% 201 255 229 #C9FFE5 African violet 288° 63% 31% 178 132 190 #B284BE Air superiority blue 205° 60% 39% 114 160 193 #72A0C1 Alabaster 46° 90% 27% 237 234 224 #EDEAE0 Alice blue 208° 97% 100% 240 248 255 #F0F8FF Alloy orange 27° 42% 85% 196 98 16 #C46210 Almond 30° 87% 52% 239 222 205 #EFDECD Amaranth 348° 53% 78% 229 43 80 #E52B50 Amaranth (M&P) 328° 40% 57% 159 43 104 #9F2B68 Amaranth pink 338° 78% 75% 241 156 187 #F19CBB Amaranth purple 342° 41% 63% 171 39 79 #AB274F Amaranth red 356° 48% 73% 211 33 45 #D3212D Amazon 147° 35% 35% 59 122 87 #3B7A57 Amber 45° 50% 100% 255 191 0 #FFBF00 Amber (SAE/ECE) 30° 50% 100% 255 126 0 #FF7E00 Amethyst 270° 60% 50% 153 102 204 #9966CC Android green 74° 50% 55% 164 198 57 #A4C639 Antique brass 22° 63% 47% 205 149 117 #CD9575 Antique bronze 52° 26% 55% 102 93 30 #665D1E Antique fuchsia 316° 46% 22% 145 92 131 #915C83 Antique ruby 350° 31% 66% 132 27 45 #841B2D Antique white 34° 91% 78% 250 235 215 #FAEBD7 Ao (English) 120° 25% 100% 0 128 0 #008000 Apple green 74° 36% 100% 141 182 0 #8DB600 Apricot 24° 84% 90% 251 206 177 #FBCEB1 Aqua 180° 50% 100% 0 255 255 #00FFFF Aquamarine 160° 75% 100% 127 255 212 #7FFFD4 Swatch Name HLS RGB HEX Arctic lime 72° 54% 100% 208 255 20 #D0FF14 Army green 69° 23% 44% 75 83 32 #4B5320 Artichoke 76° 53% 13% 143 151 121 #8F9779 Arylide yellow 51° 67% 74% 233 214 107 #E9D66B Ash gray 135° 72% 8% 178 190 -

Standard Abbreviations for Common Names of Birds M

Standard abbreviations for common names of birds M. Kathleen Klirnkiewicz I and Chandler $. I•obbins 2 During the past two decadesbanders have taken The system we proposefollows five simple rules their work more seriouslyand have begun record- for abbreviating: ing more and more informationregarding the birds they are banding. To facilitate orderly record- 1. If the commonname is a singleword, use the keeping,bird observatories(especially Manomet first four letters,e.g., Canvasback, CANV. and Point Reyes)have developedstandard record- 2. If the common name consistsof two words, use ing forms that are now available to banders.These the first two lettersof the firstword, followed by forms are convenientfor recordingbanding data the first two letters of the last word, e.g., manually, and they are designed to facilitate Common Loon, COLO. automateddata processing. 3. If the common name consists of three words Because errors in species codes are frequently (with or without hyphens),use the first letter of detectedduring editing of bandingschedules, the the first word, the first letter of the secondword, Bird BandingOffices feel that bandersshould use and the first two lettersof the third word, e.g., speciesnames or abbreviationsthereof rather than Pied-billed Grebe, PBGR. only the AOU or speciescode numbers on their field sheets.Thus, it is essentialthat any recording 4. If the common name consists of four words form have provision for either common names, (with or without hypens), use the first letter of Latin names, or a suitable abbreviation. Most each word, •.g., Great Black-backed Gull, recordingforms presentlyin use have a 4-digit GBBG.