Carcharhinus Hemiodon, Pondicherry Shark

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Shark and Ray Products in the Processing Centres Of

S H O R T R E P O R T ALIFA BINTHA HAQUE BINTHA ALIFA 6 TRAFFIC Bulletin Vol. 30 No. 1 (2018) TRAFFIC Bulletin 30(1) 1 May 2018 FINAL.indd 8 5/1/2018 5:04:26 PM S H O R T R E P O R T OBSERVATIONS OF SHARK AND RAY Introduction PRODUCTS IN THE PROCESSING early 30% of all shark and ray species are now designated as Threatened or Near Threatened with extinction CENTRES OF BANGLADESH, according to the IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. This is a partial TRADEB IN CITES SPECIES AND understanding of the threat status as 47% of shark species have not CONSERVATION NEEDS yet been assessed owing to data deficiency (Camhi et al., 2009;N Bräutigam et al., 2015; Dulvy et al., 2014). Many species are vulnerable due to demand for their products Alifa Bintha Haque, and are particularly prone to unsustainable fishing practices Aparna Riti Biswas and (Schindler et al., 2002; Clarke et al., 2007; Dulvy et al., Gulshan Ara Latifa 2008; Graham et al., 2010; Morgan and Carlson, 2010). Sharks are exploited primarily for their fins, meat, cartilage, liver oil and skin (Clarke, 2004), whereas rays are targeted for their meat, skin, gill rakers and livers. Most shark catch takes place in response to demand for the animals’ fins, which command high prices (Jabado et al., 2015). Shark fin soup is a delicacy in many Asian countries—predominantly China—and in many other countries (Clarke et al., 2007). Apart from the fins being served in high-end restaurants, there is a demand for other products in different markets and by different consumer groups, and certain body parts are also used medicinally (Clarke et al., 2007). -

Extinction Risk and Conservation of the World's Sharks and Rays

RESEARCH ARTICLE elife.elifesciences.org Extinction risk and conservation of the world’s sharks and rays Nicholas K Dulvy1,2*, Sarah L Fowler3, John A Musick4, Rachel D Cavanagh5, Peter M Kyne6, Lucy R Harrison1,2, John K Carlson7, Lindsay NK Davidson1,2, Sonja V Fordham8, Malcolm P Francis9, Caroline M Pollock10, Colin A Simpfendorfer11,12, George H Burgess13, Kent E Carpenter14,15, Leonard JV Compagno16, David A Ebert17, Claudine Gibson3, Michelle R Heupel18, Suzanne R Livingstone19, Jonnell C Sanciangco14,15, John D Stevens20, Sarah Valenti3, William T White20 1IUCN Species Survival Commission Shark Specialist Group, Department of Biological Sciences, Simon Fraser University, Burnaby, Canada; 2Earth to Ocean Research Group, Department of Biological Sciences, Simon Fraser University, Burnaby, Canada; 3IUCN Species Survival Commission Shark Specialist Group, NatureBureau International, Newbury, United Kingdom; 4Virginia Institute of Marine Science, College of William and Mary, Gloucester Point, United States; 5British Antarctic Survey, Natural Environment Research Council, Cambridge, United Kingdom; 6Research Institute for the Environment and Livelihoods, Charles Darwin University, Darwin, Australia; 7Southeast Fisheries Science Center, NOAA/National Marine Fisheries Service, Panama City, United States; 8Shark Advocates International, The Ocean Foundation, Washington, DC, United States; 9National Institute of Water and Atmospheric Research, Wellington, New Zealand; 10Global Species Programme, International Union for the Conservation -

An Introduction to the Classification of Elasmobranchs

An introduction to the classification of elasmobranchs 17 Rekha J. Nair and P.U Zacharia Central Marine Fisheries Research Institute, Kochi-682 018 Introduction eyed, stomachless, deep-sea creatures that possess an upper jaw which is fused to its cranium (unlike in sharks). The term Elasmobranchs or chondrichthyans refers to the The great majority of the commercially important species of group of marine organisms with a skeleton made of cartilage. chondrichthyans are elasmobranchs. The latter are named They include sharks, skates, rays and chimaeras. These for their plated gills which communicate to the exterior by organisms are characterised by and differ from their sister 5–7 openings. In total, there are about 869+ extant species group of bony fishes in the characteristics like cartilaginous of elasmobranchs, with about 400+ of those being sharks skeleton, absence of swim bladders and presence of five and the rest skates and rays. Taxonomy is also perhaps to seven pairs of naked gill slits that are not covered by an infamously known for its constant, yet essential, revisions operculum. The chondrichthyans which are placed in Class of the relationships and identity of different organisms. Elasmobranchii are grouped into two main subdivisions Classification of elasmobranchs certainly does not evade this Holocephalii (Chimaeras or ratfishes and elephant fishes) process, and species are sometimes lumped in with other with three families and approximately 37 species inhabiting species, or renamed, or assigned to different families and deep cool waters; and the Elasmobranchii, which is a large, other taxonomic groupings. It is certain, however, that such diverse group (sharks, skates and rays) with representatives revisions will clarify our view of the taxonomy and phylogeny in all types of environments, from fresh waters to the bottom (evolutionary relationships) of elasmobranchs, leading to a of marine trenches and from polar regions to warm tropical better understanding of how these creatures evolved. -

Malaysia National Plan of Action for the Conservation and Management of Shark (Plan2)

MALAYSIA NATIONAL PLAN OF ACTION FOR THE CONSERVATION AND MANAGEMENT OF SHARK (PLAN2) DEPARTMENT OF FISHERIES MINISTRY OF AGRICULTURE AND AGRO-BASED INDUSTRY MALAYSIA 2014 First Printing, 2014 Copyright Department of Fisheries Malaysia, 2014 All Rights Reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, including photocopy, recording, or any information storage and retrieval system, without prior permission in writing from the Department of Fisheries Malaysia. Published in Malaysia by Department of Fisheries Malaysia Ministry of Agriculture and Agro-based Industry Malaysia, Level 1-6, Wisma Tani Lot 4G2, Precinct 4, 62628 Putrajaya Malaysia Telephone No. : 603 88704000 Fax No. : 603 88891233 E-mail : [email protected] Website : http://dof.gov.my Perpustakaan Negara Malaysia Cataloguing-in-Publication Data ISBN 978-983-9819-99-1 This publication should be cited as follows: Department of Fisheries Malaysia, 2014. Malaysia National Plan of Action for the Conservation and Management of Shark (Plan 2), Ministry of Agriculture and Agro- based Industry Malaysia, Putrajaya, Malaysia. 50pp SUMMARY Malaysia has been very supportive of the International Plan of Action for Sharks (IPOA-SHARKS) developed by FAO that is to be implemented voluntarily by countries concerned. This led to the development of Malaysia’s own National Plan of Action for the Conservation and Management of Shark or NPOA-Shark (Plan 1) in 2006. The successful development of Malaysia’s second National Plan of Action for the Conservation and Management of Shark (Plan 2) is a manifestation of her renewed commitment to the continuous improvement of shark conservation and management measures in Malaysia. -

Observer-Based Study of Targeted Commercial Fishing for Large Shark Species in Waters Off Northern New South Wales

Observer-based study of targeted commercial fishing for large shark species in waters off northern New South Wales William G. Macbeth, Pascal T. Geraghty, Victor M. Peddemors and Charles A. Gray Industry & Investment NSW Cronulla Fisheries Research Centre of Excellence P.O. Box 21, Cronulla, NSW 2230, Australia Northern Rivers Catchment Management Authority Project No. IS8-9-M-2 November 2009 Industry & Investment NSW – Fisheries Final Report Series No. 114 ISSN 1837-2112 Observer-based study of targeted commercial fishing for large shark species in waters off northern New South Wales November 2009 Authors: Macbeth, W.G., Geraghty, P.T., Peddemors, V.M. and Gray, C.A. Published By: Industry & Investment NSW (now incorporating NSW Department of Primary Industries) Postal Address: Cronulla Fisheries Research Centre of Excellence, PO Box 21, Cronulla, NSW, 2230 Internet: www.industry.nsw.gov.au © Department of Industry and Investment (Industry & Investment NSW) and the Northern Rivers Catchment Management Authority This work is copyright. Except as permitted under the Copyright Act, no part of this reproduction may be reproduced by any process, electronic or otherwise, without the specific written permission of the copyright owners. Neither may information be stored electronically in any form whatsoever without such permission. DISCLAIMER The publishers do not warrant that the information in this report is free from errors or omissions. The publishers do not accept any form of liability, be it contractual, tortuous or otherwise, for the contents of this report for any consequences arising from its use or any reliance placed on it. The information, opinions and advice contained in this report may not relate to, or be relevant to, a reader’s particular circumstance. -

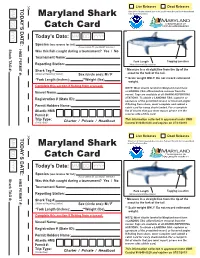

MD Shark Catch Card

Live Releases Dead Releases TODAY’S DATE: DATE: TODAY’S MM Write the # of sharks released alive in the Live Releases Box and the # released dead Maryland Shark in the Dead Release Box. DD Catch Card YYYY Today’s Date: MM DD YYYY Species (see reverse for list): If you cannot ID, you MUST release it Shark TAG #: Shark TAG HMS PERMIT #: Was this fish caught during a tournament? Yes / No Tournament Name: Fork Length Tagging Location Reporting Station: *Measurement Description Shark Tag #: * Measure in a straight line from the tip of the (Obtain at Reporting Station) Sex (circle one): M / F snout to the fork of the tail. *Fork Length (inches): **Weight (lbs) ** Scale weight ONLY. Do not record estimated weight. Complete this section if fishing from a vessel: NOTE: Most sharks landed in Maryland must have Vessel Name: a LANDING TAG affixed before removal from the vessel. Tags are available at all SHARK REPORTING STATIONS. To obtain a LANDING TAG, captains or Registration # (State ID): operators of the permitted vessel, or licensed angler if fishing from shore, must complete and submit a Permit Holders Name: catch card for every shark landed. For a complete Atlantic HMS list of sharks that you must report, please see the Permit #: reverse side of this card. Trip Type: Charter / Private / Headboat This information collected is approved under OMB (Circle One) Control # 0648-0328 and expires on 07/31/2019 Live Releases Dead Releases TODAY’S DATE: DATE: TODAY’S MM Write the # of sharks released alive in the Live Releases Box and the # released dead Maryland Shark in the Dead Release Box. -

1 Decline in CPUE of Oceanic Sharks In

IOTC-2009-WPEB-17 IOTC Working Party on Ecosystems and Bycatch; 12-14 October 2009; Mombasa, Kenya. Decline in CPUE of Oceanic Sharks in the Indian EEZ : Urgent Need for Precautionary Approach M.E. John1 and B.C. Varghese2 1 Fishery Survey of India, Mormugao Zonal Base, Goa - 403 803, India 2 Fishery Survey of India, Cochin Zonal Base, Cochin - 682 005, India Abstract The Catch Per Unit Effort (CPUE) and its variability observed in resources surveys reflect on the standing stock of the resource and the changes in the stock density. Data on the CPUE of sharks obtained in tuna longline survey in the Indian EEZ by Govt. of India survey vessels during 1984 – 2006 were considered in this study. A total effort of 3.092 million hooks yielded 20,884 sharks. 23 species belonging to five families were recorded. Average hooking rate was 0.68 percent which showed high degree of spatio-temporal variability. Sharp decline was observed in the hooking rate from the different regions. The trend in the CPUE is a clear indication of the decline in the abundance of sharks in the different regions of the EEZ, the most alarming scenario being on the west coast as well as the east coast, where the average hooking rate recorded during the last five years was less than 0.1 percent. It is evident from the results of the survey that the standing stock of several species of sharks in the Indian seas has declined to such levels that the sustainability of the resource is under severe stress requiring urgent conservation and management measures. -

AC26 WG4 Doc. 1

AC26 WG4 Doc. 1 CONVENTION ON INTERNATIONAL TRADE IN ENDANGERED SPECIES OF WILD FAUNA AND FLORA ____________ Twenty-sixth meeting of the Animals Committee Geneva (Switzerland), 15-20 March 2012 and Dublin (Ireland), 22-24 March 2012 IMPLEMENTATION OF RESOLUTION CONF. 12.6 (REV. COP15) ON CONSERVATION AND MANAGEMENT OF SHARKS (CLASS CHONDRICHTHYES) DRAFT PROPOSAL TO INCLUDE LAMNA NASUS IN APPENDIX II (Agenda items 16 and 26.2) Membership (as decided by the Committee) Chairs: representative of Oceania (Mr Robertson) as Chair and alternate representative of Asia (Mr Ishii) as Vice-Chair; Parties: Australia, Belgium, Brazil, Canada, China, Czech Republic, Germany, Ireland, Japan, Norway, Poland, Republic of Korea, Slovakia, South Africa, Spain, United Kingdom and United States; and IGOs and NGOs: European Union, Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, IUCN – International Union for Conservation of Nature, SEAFDEC – Southeast Asian Fisheries Development Center, Animal Welfare Institute, Defenders of Wildlife, Fundación Cethus, Humane Society of the United States, Pew Environment Group, Project AWARE Foundation, Species Management Specialists, Species Survival Network, SWAN International, TRAFFIC International and Wildlife Conservation Society, WWF. Mandate In support of the implementation of Resolution Conf. 12.6 (Rev. CoP15) and reporting by the Animals Committee at the 16th meeting of the Conference of the Parties (CoP16), the working group shall: 1. Examine the information provided by range States on trade and other relevant data in response to Notifications to the Parties Nos. 2010/027 and 2011/049 and taking into account discussions in plenary, together with the final report of the joint FAO/CITES Workshop to review the application and effectiveness of international regulatory measures for the conservation and sustainable use of elasmobranchs (Italy, 2010) and other relevant information; 2. -

Species Composition of the Largest Shark Fin Retail-Market in Mainland

www.nature.com/scientificreports OPEN Species composition of the largest shark fn retail‑market in mainland China Diego Cardeñosa1,2*, Andrew T. Fields1, Elizabeth A. Babcock3, Stanley K. H. Shea4, Kevin A. Feldheim5 & Demian D. Chapman6 Species‑specifc monitoring through large shark fn market surveys has been a valuable data source to estimate global catches and international shark fn trade dynamics. Hong Kong and Guangzhou, mainland China, are the largest shark fn markets and consumption centers in the world. We used molecular identifcation protocols on randomly collected processed fn trimmings (n = 2000) and non‑ parametric species estimators to investigate the species composition of the Guangzhou retail market and compare the species diversity between the Guangzhou and Hong Kong shark fn retail markets. Species diversity was similar between both trade hubs with a small subset of species dominating the composition. The blue shark (Prionace glauca) was the most common species overall followed by the CITES‑listed silky shark (Carcharhinus falciformis), scalloped hammerhead shark (Sphyrna lewini), smooth hammerhead shark (S. zygaena) and shortfn mako shark (Isurus oxyrinchus). Our results support previous indications of high connectivity between the shark fn markets of Hong Kong and mainland China and suggest that systematic studies of other fn trade hubs within Mainland China and stronger law‑enforcement protocols and capacity building are needed. Many shark populations have declined in the last four decades, mainly due to overexploitation to supply the demand for their fns in Asia and meat in many other countries 1–4. Mainland China was historically the world’s second largest importer of shark fns and foremost consumer of shark fn soup, yet very little is known about the species composition of shark fns in this trade hub2. -

A New Bathyal Shark Fauna from the Pleistocene Sediments of Fiumefreddo (Sicily, Italy)

A new bathyal shark fauna from the Pleistocene sediments of Fiumefreddo (Sicily, Italy) Stefano MARSILI Dipartimento di Scienze della Terra, Università di Pisa, Via S. Maria, 53, I-56126 Pisa (Italy) [email protected] and marsili76@@gmail.com Marsili S. 2007. — A new bathyal shark fauna from the Pleistocene sediments of Fiumefreddo (Sicily, Italy). Geodiversitas 29 (2) : 229-247. ABSTRACT A new shark fauna is described from the lower-middle Pleistocene marine sediments outcropping near the Fiumefreddo village, Southern Italy. Th e fos- sil assemblage mostly consists of teeth belonging to the bathydemersal and bathypelagic elasmobranch species Chlamydoselachus anguineus, Apristurus sp., Galeus cf. melastomus, Etmopterus sp., Centroscymnus cf. crepidater, Scymnodon cf. ringens, Centrophorus cf. granulosus and C. cf. squamosus, commonly recorded along the extant outer continental shelf and upper slope. From a bathymetrical KEY WORDS point of view, the present vertical distribution of the taxa collected allows an Elasmobranchii, estimate of a depth between 500 and 1000 m. Th e bathyal character of the sharks, bathyal, fauna provides new evidence of a highly diversifi ed and heterogeneous deep-sea teeth, Mediterranean Plio-Pleistocene marine fauna, in response to the climatic and paleobiogeography, hydrographical changes. Finally, the Fiumefreddo fauna provides new relevant Pleistocene, Sicily, data for the understanding of the processes involved in the evolution of the Italy. extant Mediterranean selachian fauna. RÉSUMÉ Une nouvelle faune de requins bathyaux des sédiments du Pléistocène de Fiume- freddo (Sicile, Italie). Une nouvelle faune de sélaciens bathyaux est décrite des sédiments marins du Pléistocène inférieur-moyen de Fiumefreddo, Italie méridionale. L’association fossile comprend en majorité des dents attribuées à des espèces d’élasmobranches bathydémersaux et bathypélagiques Chlamydoselachus anguineus, Apristurus sp., GEODIVERSITAS • 2007 • 29 (2) © Publications Scientifi ques du Muséum national d’Histoire naturelle, Paris. -

Olfactory Morphology of Carcharhinid and Sphyrnid Sharks: Does the Cephalofoil Confer a Sensory Advantage?

JOURNAL OF MORPHOLOGY 264:253–263 (2005) Olfactory Morphology of Carcharhinid and Sphyrnid Sharks: Does the Cephalofoil Confer a Sensory Advantage? Stephen M. Kajiura,1* Jesica B. Forni,2 and Adam P. Summers2 1Department of Biological Sciences, Florida Atlantic University, Boca Raton, Florida 33431 2Ecology and Evolutionary Biology, University of California, Irvine, California 92697 ABSTRACT Many hypotheses have been advanced to eses fall into three categories: 1) enhanced olfactory explain the adaptive significance of the sphyrnid cephalo- klinotaxis, 2) increased olfactory acuity, and 3) foil, including potential advantages of spacing the olfac- larger sampling swath of the surrounding medium. tory organs at the distal tips of the broad surface. We To put these hypotheses into a quantifiable con- employed comparative morphology to test whether the text, consider the probability that an odorant mole- sphyrnid cephalofoil provides better stereo-olfaction, in- creases olfactory acuity, and samples a greater volume of cule binds to a receptor in the nasal rosette. The the medium compared to the situation in carcharhiniform number of odorant molecules that cross the olfactory sharks. The broadly spaced nares provide sphyrnid spe- epithelium is: cies with a significantly greater separation between the olfactory rosettes, which could lead to an enhanced ability N˙ (moles secϪ1) ϭ C(moles cmϪ3) to resolve odor gradients. In addition, most sphyrnid spe- 2 Ϫ1 cies possess prenarial grooves that greatly increase the An(cm )V(cm sec ) (1) volume of water sampled by the nares and thus increase the probability of odorant encounter. However, despite a where C is the concentration of odor molecules, An is much greater head width, and a significantly greater the area sampled by the naris, and V is the velocity number of olfactory lamellae, scalloped hammerhead of odorant over the olfactory rosette (Fig. -

Pdf 1005.43 K

Egyptian Journal of Aquatic Biology & Fisheries Zoology Department, Faculty of Science, Ain Shams University, Cairo, Egypt. ISSN 1110 – 6131 Vol. 23(4): 503 – 519 (2019) www.ejabf.journals.ekb.eg New records, conservation status and pectoral fin description of eight shark species in the Egyptian Mediterranean waters. Walaa M. Shaban* and Mohamed A. M. El-Tabakh Zoology Department, Marine Biology and Fish Sciences section, Faculty of Science, Al-Azhar University, Cairo, Egypt *Corresponding author: [email protected] ARTICLE INFO ABSTRACT Article History: For a taxonomical purpose, the present study described and analyzed the Received: Oct. 12, 2019 pectoral fin shape and measurements of shark specimens, collected from the Accepted: Nov. 6, 2019 Egyptian Mediterranean Sea waters at Alexandria, during the period from Online: Nov. 11, 2019 May 2017 to June 2018. Morphology and morphometric fin characters were _______________ used taxonomically to differentiate between shark species via photo program analysis. After confirming the identification of sharks, a list of shark species Keywords: in the Egyptian Mediterranean waters was given with emphasize on new Shark record species as well as the conservation status of each species. Pectoral fin Results showed that the collected specimens belong to eight species Morphometric analysis from different six families belonging to four orders. Species-list of sharks in New Record this study including; Heptranchias perlo, Hexanchus griseus, Squalus Conservation status megalops, Centrophorus uyato, Oxynotus centrina, Squatina squatina, Mediterranean Sea Isurus oxyrinchus and Isurus paucus. By comparing the present findings Egypt with the previous studies, three shark species out of these eight species were considered as new records in the Egyptian Mediterranean waters.