History of Education in Westmorland

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Crosby Ravensworth, Cumbria

CASE STUDY Crosby Ravensworth, Cumbria This community led housing Background project was based in Crosby The Crosby Ravensworth community led housing project Ravensworth, Cumbria. The started with a community plan which had 41 action points, development comprised of the second most important being affordable housing. 19 homes in total – 7 self- build plots, 2 homes for The Lyvennet Community Plan Group (made up of communities shared ownership and 10 from Crosby Ravensworth, Kings Meaburn, Maulds Meaburn homes for affordable rent. and Reagill) then set up the Lyvennet Community Trust with the aim of delivering affordable housing in the area. This community led housing project acted as a catalyst Eden District Council was a key partner and provided a loan for a number of community to the project. The local authority part-funded specialist asset developments in the support from Cumbria Rural Housing Trust and carried out a Eden Valley, including the housing needs survey which highlighted the need for up to 23 acquisition of the local pub, affordable dwellings. nursery provision and an A dedicated community land trust (Lyvennet Community Trust) anaerobic digester project. was set up as a company limited by guarantee and a registered This project was not just charity. The Lyvennet Community Trust secured Registered about satisfying the affordable Provider status with the Homes and Communities Agency. housing need in Crosby Ravensworth, it was also about A large derelict industrial site was chosen as a potential addressing broader issues of location and, on the strength of a strong business plan, a loan derelict sites which impact of £300,000 was secured from Charities Aid Foundation. -

Lyvennet - Our Journey

Lyvennet - Our Journey David Graham 24th September 2014 Agenda • Location • Background • Housing • Community Pub • Learning • CLT Network Lyvennet - Location The Lyvennet Valley • Villages - Crosby Ravensworth, Maulds Meaburn, Reagill and Sleagill • Population 750 • Shop – 4mls • Bank – 7 mls • A&E – 30mls • Services – • Church, • Primary School, • p/t Post Office • 1 bus / week • Pub The Start – late 2008 • Community Plan • Housing Needs Survey • Community Feedback Cumbria Rural Housing Trust Community Land Trust (CLT) The problem • 5 new houses in last 15 years • Service Centre but losing services • Stagnating • Affordability Ratio 9.8 (House price / income) Lyvennet Valley 5 Yearly Average House Price £325 Cumbria £300 £275 0 £250 0 Average 0 , £ £225 £182k £200 £175 £150 2000- 2001- 2002- 2003- 2004- 2005- 2006- 2004 2005 2006 2007 2008 2009 2010 Years LCT “Everything under one roof” Local Residents Volunteers Common interest Various backgrounds Community ‘activists’ Why – Community Land Trust • Local occupancy a first priority • No right to buy • Remain in perpetuity for the benefit of the community • All properties covered by a Local Occupancy agreement. • Reduced density of housing • Community control The community view was that direct local stewardship via a CLT with expert support from a housing association is the right option, removing all doubt that the scheme will work for local people. Our Journey End March2011 Tenders Lyvennet 25th Jan -28th Feb £660kHCAFunding Community 2011 £1mCharityBank Developments FullPlanning 25th -

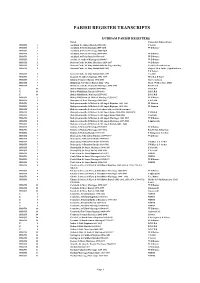

Parish Register Transcripts

PARISH REGISTER TRANSCRIPTS DURHAM PARISH REGISTERS Parish Transcriber/Indexer/Donor PR.DUR 1 Auckland, St Andrew Burials 1559-1653 C Jewitt PR.DUR 1 Auckland, St Helen Baptisms 1559-1635 W E Rounce PR.DUR 1 Auckland, St Helen Marriages 1559-1635 PR.DUR 1 Auckland, St Helen Marriages 1593-1837 W E Rounce PR.DUR 1 Auckland, St Helen Burials 1559-1635 W E Rounce PR.DUR 1 Aycliffe, St Andrew Marriages 1560-1837 W E Rounce PR.DUR 2 Barnard Castle, St Mary Marriages 1619-1837 W E Rounce PR.DUR 2 Barnard Castle, St Mary Burials 1816-48 (Pages missing) Teesdale Record Society PR.DUR 2 Barnard Castle, St Mary Burials 1688-1812 Major L M K Fuller (Typed/indexed: P R Joiner) PR.DUR 2 Barnard Castle, St Mary Burials 1813-1815 C Jewitt PR.DUR 3 Beamish, St Andrew Baptisms 1876-1897 M G B & E Yard PR.DUR 3 Belmont Cemetery Burials 1936-2000 Harry Aichison PR.DUR 3 Billingham St Cuthbert Burials 1662 - 1812 Mrs I. Walker (Clev. FHS) PR.DUR 3 Birtley, St John the Evangelist Marriages 1850-1910 R & D Tait Z 19 Bishop Middleham, Baptisms 1559-1812 D.N.P.R.S Z 19 Bishop Middleham, Burials 1559-1812 D.N.P.R.S Z 19 Bishop Middleham, Marriages 1559-1812 D.N.P.R.S PR.DUR 3 Bishop Middleham, St Michael Marriages 1559-1837 W E Rounce PR.DUR 3 Bishopton, St Peter Marriages 1653-1861 J.W Todd PR.DUR 4 Bishopwearmouth, St Michael & All Angels Baptisms 1813-1841 M Johnson PR.DUR 4 Bishopwearmouth, St Michael & All Angels Baptisms 1835-1841 M Johnson PR.DUR 5 Bishopwearmouth (Section at back shows widows & fathers names) PR.DUR 5 Bishopwearmouth, St Michael & All -

Affordable Homes for Local People: the Effects and Prospects

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by University of Liverpool Repository Affordable homes for local communities: The effects and prospects of community land trusts in England Dr Tom Moore August 2014 Acknowledgements This research study was funded by the British Academy Small Grants scheme (award number: SG121627). It was conducted during the author’s employment at the Centre for Housing Research at the University of St Andrews. He is now based at the University of Sheffield. Thanks are due to all those who participated in the research, particularly David Graham of Lyvennet Community Trust, Rosemary Heath-Coleman of Queen Camel Community Land Trust, Maria Brewster of Liverpool Biennial, and Jayne Lawless and Britt Jurgensen of Homebaked Community Land Trust. The research could not have been accomplished without the help and assistance of these individuals. I am also grateful to Kim McKee of the University of St Andrews and participants of the ESRC Seminar Series event The Big Society, Localism and the Future of Social Housing (held in St Andrews on 13-14th March 2014) for comments on previous drafts and presentations of this work. All views expressed in this report are solely those of the author. For further information about the project and future publications that emerge from it, please contact: Dr Tom Moore Interdisciplinary Centre of the Social Sciences University of Sheffield 219 Portobello Sheffield S1 4DP Email: [email protected] Telephone: 0114 222 8386 Twitter: @Tom_Moore85 Contents Executive Summary .................................................................................................................................. i 1. Introduction to CLTs ........................................................................................................................ 1 1.2 The policy context: localism and community-led housing ........................................................... -

The Multiple Estate: a Framework for the Evolution of Settlement in Anglo-Saxon and Scandinavian Cumbria

THE MULTIPLE ESTATE: A FRAMEWORK FOR THE EVOLUTION OF SETTLEMENT IN ANGLO-SAXON AND SCANDINAVIAN CUMBRIA Angus J. L. Winchester In general, it is not until the later thirteenth century that surv1vmg documents enable us to reconstruct in any detail the pattern of rural settlement in the valleys and plains of Cumbria. By that time we find a populous landscape, the valleys of the Lake District supporting communi ties similar in size to those which they contained in the sixteenth century, the countryside peppered with corn mills and fulling mills using the power of the fast-flowing becks to process the produce of field and fell. To gain any idea of settlement in the area at an earlier date from documentary sources, we are thrown back on the dry, bare bones of the structure of landholding provided by a scatter of contemporary documents, including for southern Cumbria a few bald lines in the Domesday survey. This paper aims to put some flesh on the evidence of these early sources by comparing the patterns of lordship which they reveal in different parts of Cumbria and by drawing parallels with other parts of the country .1 Central to the argument pursued below is the concept of the multiple estate, a compact grouping of townships which geographers, historians and archaeologists are coming to see as an ancient, relatively stable framework within which settlement in northern England evolved during the centuries before the Norman Conquest. The term 'multiple estate' has been coined by G. R. J. Jones to describe a grouping of settlements linked -

(Public Pack)Agenda Document for Executive, 07/04/2020 18:00

Date: 30 March 2020 Town Hall, Penrith, Cumbria CA11 7QF Tel: 01768 817817 Email: [email protected] Dear Sir/Madam Executive Agenda - 7 April 2020 Notice is hereby given that a meeting of the Executive will be held at 6.00 pm on Tuesday, 7 April 2020 at the Town Hall, Penrith. 1 Apologies for Absence 2 Minutes RECOMMENDATION that the public minutes E/84/02/20 to E/95/02/20 of the meeting of the Executive held on 25 February 2020 be confirmed and approved by the Chairman as a correct record of those proceedings (copies previously circulated). 3 Declarations of Interest To receive declarations of the existence and nature of any private interests, both disclosable pecuniary and any other registrable interests, in any matter to be considered or being considered. 4 Questions and Representations from the Public To receive questions and representations from the public under Rules 3 and 4 of the Executive Procedure Rules of the Constitution 5 Questions from Members To receive questions and representations from Members under Rule 5 of the Executive Procedure Rules of the Constitution 6 Eden Community Fund Recommendations - Communities Portfolio Holder (Pages 5 - 12) To consider report PP14/20 from the Assistant Director Community Services which is attached and which seeks approval for the award from the Eden Community Fund of grants to the 10 projects set out in Appendix A. RECOMMENDATION that a grant from the Eden Community Fund is agreed for each of the 10 projects set out in Appendix A, to a total of £55,900.88. -

Kendal & Local Business Listings 23-04-20

Table 1 Name Phone Number Products/Services Area Covered Delivery Additional Information Availability Bakers Bakery At No 4 07500 772134 Brownies, flapjacks, tiffins, shortbreads, Kendal & local radius Dependent on Currently closed for business. sponges, loaves (sweet), cakes. product availability Banilla Bakery Vegan Cakes 07706 381797 or email Vegan brownie boxes, cake jars, cupcakes. All Kendal & local radius Free delivery Please contact us via phone, email or [email protected] products use natural ingredients. Gluten & soya Facebook messenger to place your order. free options are also available on request. Payment taken over the phone. Free non- contact delivery. Decadent Bakes 07889 877660 Brownie slices & jars, cakes & cupcakes. Kendal & local radius Delivery Friday, free Please place orders by 9pm on Thursdays for for orders over £10. Friday delivery, via phone or Facebook. £1 for smaller Payment over phone. orders Endmoor Bakers 01539 567559 or email clive- Bakery products. Endmoor & local radius Free delivery daily Please give 24 hours notice. [email protected] for orders over £10 Gabe’s Vegan Cakes 07588 127353 or email Gluten free, vegan & refined sugar free raw Kendal & local radius Free delivery Please order over the phone or via email. [email protected] treats, layer cakes, celebration cakes, traybakes Payment over phone. & scones. Ginger Bakers 01539 232815 Mixed boxes of tray bakes. Kendal & local radius Shop closed. Currently closed for business. Awaiting delivery setup information Little Miss Bakery 01539 736934 or email Bread loaves & buns, cakes, scones. Kendal & local radius Free delivery Please email, call or facebook message to [email protected] Tuesday & Friday place your order by 12pm Monday for a Tuesday delivery or 12pm Thursday for a Friday delivery. -

Fellside Manor Endmoor, Kendal, La8 0Ny

FELLSIDE MANOR ENDMOOR, KENDAL, LA8 0NY JOB NUMBER TITLE PG VERSION DATE Size at 100% STO *DEVELOPMENT NAME* BROCHURE 1 A4P DESIGNER Org A/W A/W AMENDS C: DATE: STRONG. BEAUTIFUL. AS A PRIVATELY-OWNED BUSINESS, WE GO TO GREAT LENGTHS TO CRAFT BEAUTIFUL, WELL-BUILT HOMES. Homes that are not only strong in build, but in character too. Story homes challenge the conventions of the mass-produced, standing apart from the crowd. There’s all the features that make a Story home unique. The space we leave between each home, and footpaths that little bit wider, because that’s what people need. Even our front doors are different colours. And the best combinations of bricks, render and stone are used, with considered design features at every turn. With a brand new Story home, you will find there are no compromises on quality, no corners cut – just solid, beautiful homes. SOLIDLY BUILT WITH BUILDING BEAUTIFUL HOMES WE’LL GIVE YOU MORE DESIGNED QUALITY MATERIALS. FOR OVER 30 YEARS. SPACE INSIDE & OUT. FOR LIFE. High specification. Pride in our homes. Well-proportioned living areas. Unique modern features. Added strength and character. Pride in our workforce. Set back off the road. Effortlessly flowing spaces. 2 3 JOB NUMBER TITLE PG VERSION DATE Size at 100% JOB NUMBER TITLE PG VERSION DATE Size at 100% STO *DEVELOPMENT NAME* BROCHURE 2 A4P STO *DEVELOPMENT NAME* BROCHURE 3 A4P DESIGNER Org A/W A/W AMENDS DESIGNER Org A/W A/W AMENDS C: DATE: C: DATE: WELCOME TO FELLSIDE MANOR Image shown is for illustrative purposes only. -

New Additions to CASCAT from Carlisle Archives

Cumbria Archive Service CATALOGUE: new additions August 2021 Carlisle Archive Centre The list below comprises additions to CASCAT from Carlisle Archives from 1 January - 31 July 2021. Ref_No Title Description Date BRA British Records Association Nicholas Whitfield of Alston Moor, yeoman to Ranald Whitfield the son and heir of John Conveyance of messuage and Whitfield of Standerholm, Alston BRA/1/2/1 tenement at Clargill, Alston 7 Feb 1579 Moor, gent. Consideration £21 for Moor a messuage and tenement at Clargill currently in the holding of Thomas Archer Thomas Archer of Alston Moor, yeoman to Nicholas Whitfield of Clargill, Alston Moor, consideration £36 13s 4d for a 20 June BRA/1/2/2 Conveyance of a lease messuage and tenement at 1580 Clargill, rent 10s, which Thomas Archer lately had of the grant of Cuthbert Baynbrigg by a deed dated 22 May 1556 Ranold Whitfield son and heir of John Whitfield of Ranaldholme, Cumberland to William Moore of Heshewell, Northumberland, yeoman. Recites obligation Conveyance of messuage and between John Whitfield and one 16 June BRA/1/2/3 tenement at Clargill, customary William Whitfield of the City of 1587 rent 10s Durham, draper unto the said William Moore dated 13 Feb 1579 for his messuage and tenement, yearly rent 10s at Clargill late in the occupation of Nicholas Whitfield Thomas Moore of Clargill, Alston Moor, yeoman to Thomas Stevenson and John Stevenson of Corby Gates, yeoman. Recites Feb 1578 Nicholas Whitfield of Alston Conveyance of messuage and BRA/1/2/4 Moor, yeoman bargained and sold 1 Jun 1616 tenement at Clargill to Raynold Whitfield son of John Whitfield of Randelholme, gent. -

Annual Report for the Year Ended the 31St March, 1963

Twelfth Annual Report for the year ended the 31st March, 1963 Item Type monograph Publisher Cumberland River Board Download date 01/10/2021 01:06:39 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/1834/26916 CUMBERLAND RIVER BOARD Twelfth Annual Report for the Year ended the 31st March, 1963 CUMBERLAND RIVER BOARD Twelfth Annual Report for the Year ended the 31st March, 1963 Chairman of the Board: Major EDWIN THOMPSON, O.B.E., F.L.A.S. Vice-Chairman: Major CHARLES SPENCER RICHARD GRAHAM RIVER BOARD HOUSE, LONDON ROAD, CARLISLE, CUMBERLAND. TELEPHONE CARLISLE 25151/2 NOTE The Cumberland River Board Area was defined by the Cumberland River Board Area Order, 1950, (S.I. 1950, No. 1881) made on 26th October, 1950. The Cumberland River Board was constituted by the Cumberland River Board Constitution Order, 1951, (S.I. 1951, No. 30). The appointed day on which the Board became responsible for the exercise of the functions under the River Boards Act, 1948, was 1st April, 1951. CONTENTS Page General — Membership Statutory and Standing Committees 4 Particulars of Staff 9 Information as to Water Resources 11 Land Drainage ... 13 Fisheries ... ... ... ........................................................ 21 Prevention of River Pollution 37 General Information 40 Information about Expenditure and Income ... 43 PART I GENERAL Chairman of the Board : Major EDWIN THOMPSON, O.B.E., F.L.A.S. Vice-Chairman : Major CHARLES SPENCER RICHARD GRAHAM. Members of the Board : (a) Appointed by the Minister of Agriculture, Fisheries and Food and by the Minister of Housing and Local Government. Wilfrid Hubert Wace Roberts, Esq., J.P. Desoglin, West Hall, Brampton, Cumb. -

Königreichs Zur Abgrenzung Der Der Kommission in Übereinstimmung

19 . 5 . 75 Amtsblatt der Europäischen Gemeinschaften Nr . L 128/23 1 RICHTLINIE DES RATES vom 28 . April 1975 betreffend das Gemeinschaftsverzeichnis der benachteiligten landwirtschaftlichen Gebiete im Sinne der Richtlinie 75/268/EWG (Vereinigtes Königreich ) (75/276/EWG ) DER RAT DER EUROPAISCHEN 1973 nach Abzug der direkten Beihilfen, der hill GEMEINSCHAFTEN — production grants). gestützt auf den Vertrag zur Gründung der Euro Als Merkmal für die in Artikel 3 Absatz 4 Buch päischen Wirtschaftsgemeinschaft, stabe c ) der Richtlinie 75/268/EWG genannte ge ringe Bevölkerungsdichte wird eine Bevölkerungs gestützt auf die Richtlinie 75/268/EWG des Rates ziffer von höchstens 36 Einwohnern je km2 zugrunde vom 28 . April 1975 über die Landwirtschaft in Berg gelegt ( nationaler Mittelwert 228 , Mittelwert in der gebieten und in bestimmten benachteiligten Gebie Gemeinschaft 168 Einwohner je km2 ). Der Mindest ten (*), insbesondere auf Artikel 2 Absatz 2, anteil der landwirtschaftlichen Erwerbspersonen an der gesamten Erwerbsbevölkerung beträgt 19 % auf Vorschlag der Kommission, ( nationaler Mittelwert 3,08 % , Mittelwert in der Gemeinschaft 9,58 % ). nach Stellungnahme des Europäischen Parlaments , Eigenart und Niveau der vorstehend genannten nach Stellungnahme des Wirtschafts- und Sozialaus Merkmale, die von der Regierung des Vereinigten schusses (2 ), Königreichs zur Abgrenzung der der Kommission mitgeteilten Gebiete herangezogen wurden, ent sprechen den Merkmalen der in Artikel 3 Absatz 4 in Erwägung nachstehender Gründe : der Richtlinie -

WSSPPX6 2013-14 A

THE WEEKLY MAGAZINE DEDICATED TO WOMEN’S AND GIRLS FOOTBALL SUPER EAGLES SHOCK DERBY * LIVERPOOL START TITLE DEFENCE WITH HOME MATCH * FA Women’s Cup Final heading for Milton Keynes * New sponsorship deals for Albion and Forest * Title winners Solar looking set for sunny future * F.A.Women’s Cup - Road to the Final Featuring ALL the Women’s Leagues across the country… ACTION Shots . (above) Charlton Athletic’s Grace Coombs gets in a tackle on Kerry Parkin of Sheffield FC (www.jamesprickett.co.uk). (below) Plymouth Argyle striker Jodie Chubb beats Brighton & Hove Albion goalkeeper Toni Anne Wayne with a shot that hits the post (David Potham). [email protected] The FA WSL fixtures for the new campaign have been announced and Champions Liverpool start the defence of their title at home to newcomers Manchester City. Last season's runners-up Bristol Academy host Emma Hayes' new look Chelsea side whilst Arsenal have a difficult game away to Notts County. The announcement was made on BT Sport, who will broadcast that match live on Thursday 17th April, one day after the top flight starts its fourth season. The FA WSL 2 will begin the same week with Oxford Utd hosting London Bees on Monday 14th April. Doncaster Rovers Belles, who will be aiming to reclaim their top flight status at the first attempt, travel to Aston Villa whilst Reading Women's match with Yeovil Town will be at the Madejski Stadium. The Continental Cup will start its matches on Thursday 1st May and the eighteen teams have been split into three groups of six.