Lithuania Under the Sickle and Hammer

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

On the Threshold of the Holocaust: Anti-Jewish Riots and Pogroms In

Geschichte - Erinnerung – Politik 11 11 Geschichte - Erinnerung – Politik 11 Tomasz Szarota Tomasz Szarota Tomasz Szarota Szarota Tomasz On the Threshold of the Holocaust In the early months of the German occu- volume describes various characters On the Threshold pation during WWII, many of Europe’s and their stories, revealing some striking major cities witnessed anti-Jewish riots, similarities and telling differences, while anti-Semitic incidents, and even pogroms raising tantalising questions. of the Holocaust carried out by the local population. Who took part in these excesses, and what was their attitude towards the Germans? The Author Anti-Jewish Riots and Pogroms Were they guided or spontaneous? What Tomasz Szarota is Professor at the Insti- part did the Germans play in these events tute of History of the Polish Academy in Occupied Europe and how did they manipulate them for of Sciences and serves on the Advisory their own benefit? Delving into the source Board of the Museum of the Second Warsaw – Paris – The Hague – material for Warsaw, Paris, The Hague, World War in Gda´nsk. His special interest Amsterdam, Antwerp, and Kaunas, this comprises WWII, Nazi-occupied Poland, Amsterdam – Antwerp – Kaunas study is the first to take a comparative the resistance movement, and life in look at these questions. Looking closely Warsaw and other European cities under at events many would like to forget, the the German occupation. On the the Threshold of Holocaust ISBN 978-3-631-64048-7 GEP 11_264048_Szarota_AK_A5HC PLE edition new.indd 1 31.08.15 10:52 Geschichte - Erinnerung – Politik 11 11 Geschichte - Erinnerung – Politik 11 Tomasz Szarota Tomasz Szarota Tomasz Szarota Szarota Tomasz On the Threshold of the Holocaust In the early months of the German occu- volume describes various characters On the Threshold pation during WWII, many of Europe’s and their stories, revealing some striking major cities witnessed anti-Jewish riots, similarities and telling differences, while anti-Semitic incidents, and even pogroms raising tantalising questions. -

Elaboration of Priority Components of the Transboundary Neman/Nemunas River Basin Management Plan (Key Findings)

Elaboration of Priority Components of the Transboundary Neman/Nemunas River Basin Management Plan (Key Findings) June 2018 Disclaimer: This report was prepared with the financial assistance of the European Union. The views expressed herein can in no way be taken to reflect the official opinion of the European Union. TABLE OF CONTENTS EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ..................................................................................................................... 3 1 OVERVIEW OF THE NEMAN RIVER BASIN ON THE TERRITORY OF BELARUS ............................... 5 1.1 General description of the Neman River basin on the territory of Belarus .......................... 5 1.2 Description of the hydrographic network ............................................................................. 9 1.3 General description of land runoff changes and projections with account of climate change........................................................................................................................................ 11 2 IDENTIFICATION (DELINEATION) AND TYPOLOGY OF SURFACE WATER BODIES IN THE NEMAN RIVER BASIN ON THE TERRITORY OF BELARUS ............................................................................. 12 3 IDENTIFICATION (DELINEATION) AND MAPPING OF GROUNDWATER BODIES IN THE NEMAN RIVER BASIN ................................................................................................................................... 16 4 IDENTIFICATION OF SOURCES OF HEAVY IMPACT AND EFFECTS OF HUMAN ACTIVITY ON SURFACE WATER BODIES -

Impact of Climate Change and Other Abiotic Environmental Factors on Aquatic Ecosystems

Environmental Research, Engineering and Management 2017/73/2 5 EDITORIAL Impact of Climate Change and Other Abiotic Environmental Factors on Aquatic Ecosystems Dr. Jūratė Kriaučiūnienė Lithuanian Energy Institute [email protected] Water ecosystems are very important for conservation impact on aquatic animal diversity and productivity, of biosphere variety and production. EU Water Frame- and carry out an integrated impact assessment accor- work Directive requires the Member States to imple- ding to the multi-annual data and climate scenarios. ment the necessary measures to improve and protect Three river basins (of the Neris, the Nevėžis and the the status of water bodies. Consequences of climate Minija) and the Curonian Lagoon have been chosen as change together with intensive use of natural reso- research objects. urces pose a threat to aquatic animal communities, During the project the following activities are planned: and in the future it will undoubtedly have even more development of the methodology for assessment of significant effect. As frequency of extreme climatic climate change impact on the state of aquatic ecosys- events increases, aquatic ecosystems will be forced tem; projection of changes of significant for aquatic to adapt to new stressful environmental conditions. ecosystem climatic indices in 21st century according There are many investigations dedicated to assess- to output data from different climate scenarios; as- ment of climate change impact on aquatic ecosystem sessment of change patterns and extremes of abio- -

The Baltics EU/Schengen Zone Baltic Tourist Map Traveling Between

The Baltics Development Fund Development EU/Schengen Zone Regional European European in your future your in g Investin n Unio European Lithuanian State Department of Tourism under the Ministry of Economy, 2019 Economy, of Ministry the under Tourism of Department State Lithuanian Tampere Investment and Development Agency of Latvia, of Agency Development and Investment Pori © Estonian Tourist Board / Enterprise Estonia, Enterprise / Board Tourist Estonian © FINL AND Vyborg Turku HELSINKI Estonia Latvia Lithuania Gulf of Finland St. Petersburg Estonia is just a little bigger than Denmark, Switzerland or the Latvia is best known for is Art Nouveau. The cultural and historic From Vilnius and its mysterious Baroque longing to Kaunas renowned Netherlands. Culturally, it is located at the crossroads of Northern, heritage of Latvian architecture spans many centuries, from authentic for its modernist buildings, from Trakai dating back to glorious Western and Eastern Europe. The first signs of human habitation in rural homesteads to unique samples of wooden architecture, to medieval Lithuania to the only port city Klaipėda and the Curonian TALLINN Novgorod Estonia trace back for nearly 10,000 years, which means Estonians luxurious palaces and manors, churches, and impressive Art Nouveau Spit – every place of Lithuania stands out for its unique way of Orebro STOCKHOLM Lake Peipus have been living continuously in one area for a longer period than buildings. Capital city Riga alone is home to over 700 buildings built in rendering the colorful nature and history of the country. Rivers and lakes of pure spring waters, forests of countless shades of green, many other nations in Europe. -

Lithuania Guidebook

LITHUANIA PREFACE What a tiny drop of amber is my country, a transparent golden crystal by the sea. -S. Neris Lithuania, a small and beautiful country on the coast of the Baltic Sea, has often inspired artists. From poets to amber jewelers, painters to musicians, and composers to basketball champions — Lithuania has them all. Ancient legends and modern ideas coexist in this green and vibrant land. Lithuania is strategically located as the eastern boundary of the European Union with the Commonwealth of Independent States. It sits astride both sea and land routes connecting North to South and East to West. The uniqueness of its location is revealed in the variety of architecture, history, art, folk tales, local crafts, and even the restaurants of the capital city, Vilnius. Lithuania was the last European country to embrace Roman Catholicism and has one of the oldest living languages on earth. Foreign and local investment is modernizing the face of the country, but the diverse cultural life still includes folk song festivals, outdoor markets, and mid- summer celebrations as well as opera, ballet and drama. This blend of traditional with a strong desire to become part of the new community of nations in Europe makes Lithuania a truly vibrant and exciting place to live. Occasionally contradictory, Lithuania is always interesting. You will sense the history around you and see history in the making as you enjoy a stay in this unique and unforgettable country. AREA, GEOGRAPHY, AND CLIMATE Lithuania, covering an area of 26,173 square miles, is the largest of the three Baltic States, slightly larger than West Virginia. -

VILNIAUS GEDIMINO TECHNIKOS UNIVERSITETAS Neringa Červokaitė EKOLOGINĖS NEVĖŽIO UPĖS SITUACIJOS VERTINIMAS IR PREVENCINĖS

VILNIAUS GEDIMINO TECHNIKOS UNIVERSITETAS APLINKOS INŽINERIJOS FAKULTETAS HIDRAULIKOS KATEDRA Neringa Červokaitė EKOLOGINĖS NEVĖŽIO UPĖS SITUACIJOS VERTINIMAS IR PREVENCINĖS GERINIMO PRIEMONĖS THE ASSESSMENT OF NEVĖŽIS RIVER’S ECOLOGICAL SITUATION AND PREVENTIVE MEASURES OF IMPROVEMENT Baigiamasis magistro darbas Vandens ūkio inžinerijos studijų programa, valstybinis kodas 62404T105 Aplinkos inžinerijos studijų kryptis Vilnius, 2011 VILNIAUS GEDIMINO TECHNIKOS UNIVERSITETAS APLINKOS INŽINERIJOS FAKULTETAS HIDRAULIKOS KATEDRA TVIRTINU Katedros vedėjas _______________________ (Parašas) _______________________ (Vardas, pavardė) ______________________ (Data) Neringa Červokaitė EKOLOGINĖS NEVĖŽIO UPĖS SITUACIJOS VERTINIMAS IR PREVENCINĖS GERINIMO PRIEMONĖS THE ASSESSMENT OF NEVĖŽIS RIVER’S ECOLOGICAL SITUATION AND PREVENTIVE MEASURES OF IMPROVEMENT Baigiamasis magistro darbas Vandens ūkio inžinerijos studijų programa, valstybinis kodas 62404T105 Aplinkos inžinerijos studijų kryptis Vadovas: prof. dr. Valentinas Šaulys__________________________________ ( Moksl. laipsnis, vardas, pavardė) (Parašas) (Data) Konsultantas: lekt. Regina Žukienė_________________________________ ( Moksl. laipsnis, vardas, pavardė) (Parašas) (Data) Vilnius, 2011 2 VILNIAUS GEDIMINO TECHNIKOS UNIVERSITETAS APLINKOS INŽINERIJOS FAKULTETAS HIDRAULIKOS KATEDRA TVIRTINU ..........................…………………....... mokslo sritis Katedros vedėjas .....................……………………......mokslo kryptis _________________________ (parašas) ..........…....………….………….…....studijų kryptis -

Available As PDF

ID Locality Administrative unit Country Alternate spelling Latitude Longitude Geographic Stratigraphic age Age, lower Age, upper Epoch Reference precision boundary boundary 3247 Acquasparta (along road to Massa Martana) Acquasparta Italy 42.707778 12.552333 1 late Villafranchian 2 1.1 Pleistocene Esu, D., Girotti, O. 1975. La malacofauna continentale del Plio-Pleistocene dell’Italia centrale. I. Paleontologia. Geologica Romana, 13, 203-294. 3246 Acquasparta (NE of 'km 32', below Chiesa di Santa Lucia di Burchiano) Acquasparta Italy 42.707778 12.552333 1 late Villafranchian 2 1.1 Pleistocene Esu, D., Girotti, O. 1975. La malacofauna continentale del Plio-Pleistocene dell’Italia centrale. I. Paleontologia. Geologica Romana, 13, 203-294. 3234 Acquasparta (Via Tiberina, 'km 32,700') Acquasparta Italy 42.710556 12.549556 1 late Villafranchian 2 1.1 Pleistocene Esu, D., Girotti, O. 1975. La malacofauna continentale del Plio-Pleistocene dell’Italia centrale. I. Paleontologia. Geologica Romana, 13, 203-294. upper Alluvial Ewald, R. 1920. Die fauna des kalksinters von Adelsheim. Jahresberichte und Mitteilungen des Oberrheinischen geologischen Vereines, Neue Folge, 3330 Adelsheim (Adelsheim, eastern part of the city) Adelsheim Germany 49.402305 9.401456 2 (Holocene) 0.00585 0 Holocene 9, 15-17. Sanko, A.F. 2007. Quaternary freshwater mollusks Belarus and neighboring regions of Russia, Lithuania, Poland (field guide). [in Russian]. Institute 5200 Adrov Adrov Belarus 54.465816 30.389993 2 Holocene 0.0117 0 Holocene of Geochemistry and Geophysics, National Academy of Sciences, Belarus. middle-late 4441 Adzhikui Adzhikui Turkmenistan 39.76667 54.98333 2 Pleistocene 0.781 0.0117 Pleistocene FreshGEN team decision Hagemann, J. 1976. Stratigraphy and sedimentary history of the Upper Cenozoic of the Pyrgos area (Western Peloponnesus), Greece. -

Vilnius Mini Guide CONTENT

Vilnius Mini Guide CONTENT 10 MUST SEE 14 INTERESTING DISTRICTS 18 ACTIVE LEISURE 22 WHERE AND WHAT TO EAT 26 WHERE TO PARTY WE VILNIANS ARE AN 28 WHERE TO SHOP 30 ART IN VILNIUS ACTIVE BUNCH. 34 PARKS IN VILNIUS 38 DAY TRIPS Vilnius can take you by surprise - many of the Lithuanian capital’s most 40 JEWISH VILNIUS beautiful secrets are kept in plain sight for all to see, and somehow there’s not too much talk about them. The UNESCO-listed medieval Old Town 42 PILGRIMAGE IN VILNIUS is home to many historical buildings and luscious parks, and the past 44 VILNIUS WITH KIDS is closely intertwined with the present. Modern street art installations, contemporary cuisine, and adventurous leisure activities are the perfect 46 BUDGET VILNIUS mix for a memorable getaway. 48 TOURS IN VILNIUS This guide gives you dozens of puzzle pieces to create your own picture 52 MEET A LOCAL of Vilnius as you see it. Welcome! 53 TIPS Vilnius Mini Guide 3 1 6 You can fly like a bird, You can have empty pockets, or at least get a bird’s-eye view but a heart full of experiences. of the Old Town from a hot-air Adventures, street art, and balloon. sightseeing can cost you 10 nothing. REASONS TO FALL IN LOVE 2 7 It’s greener than a dollar. It’s like living in Four Seasons - WITH VILNIUS Parks, squares, and nature Vilnius actually has four distinct reserves in the heart of the city seasons you can feel and make Vilnius one of the greenest explore. -

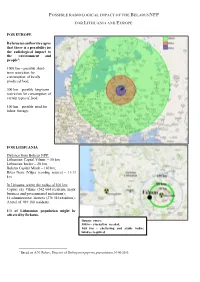

Possible Radiological Impact of the Belarus Npp For

POSSIBLE RADIOLOGICAL IMPACT OF THE BELARUS NPP FOR LITHUANIA AND EUROPE FOR EUROPE Belarusian authorities agree that there is a possibility for the radiological impact to the environment and people 1: 1000 km – possible short- term restriction for consumption of locally produced food; 300 km – possible long-term restriction for consumption of certain types of food; 100 km – possible need for iodine therapy. FOR LITHUANIA Distance from Belarus NPP: Lithuanian Capital Vilnius – 50 km; Lithuanian border – 20 km; Belarus Capital Minsk – 140 km; River Neris (Vilija) (cooling source) – 11-13 km. In Lithuania within the radius of 100 km: Capital city Vilnius (542 664 residents, major business and governmental institutions); 14 administrative districts (276 516 residents); A total of 919 180 residents. 1/3 of Lithuanian population might be affected by Belarus. Danger zones: 30km – evacuation needed; 100 km – sheltering and stable iodine intakes required. 1 Based on A.N. Rykov, Director of Belinipenergoprom, presentation, 16-06-2010. Distances from Belarus NPP site to: Capital of Lithuania Vilnius ~50 km; River Neris (Vilija) (cooling source) - ~11-13 km; Capital of Belarus Minsk ~ 140 km; Capitals within the range of 1000 km: Vilnius (~50 km); Minsk (~140 km); Riga (~300 km); Warsaw (~430 km); Tallinn (~550 km); Kiev (~560 km); Stockholm (~710 km); Copenhagen (~860 km); Berlin (~870 km). The main issues related to the nuclear and environmental safety of Belarus NPP project: Site selection and safety of site. The Espoo Convention requires to assess locational alternatives in the EIA report and to choose the project site as an outcome of the EIA procedure. -

Mobility in the Eastern Baltics (15Th–17Th Centuries) Acta Historica Universitatis Klaipedensis XXIX, 2014, 6–10

INTRODUCTION: SIT VENIA VERBO The free movement of people, goods, services and capital is one of the cornerstone prin- ciples of the Treaty on the European Union. The provisions of the treaty provide for an individual’s mobility in the social environment. We can argue that the Treaty on the Euro- pean Union creates conditions for increasingly weaker dependence on nation-states. The decentralised movement directs us primarily towards individual self-expression and the pursuit of personal benefit. Movement is encouraged away from local and towards global centres, where administrative power and economic power (production, finance and trade) are concentrated. ‘Freedom of movement’ became the main condition for the geo-political structure in the EU economic space. The new European identity is formed by this condition 6 and the provisions of the law establishing the supremacy of individual freedom/benefit. Universal mobility in the cultural space of Western Europe was also important in other periods. However, its nature and its effects were different: they were centralis- ing. West European societies were also known as ‘mobile’ in the late Middle Ages and the Early Modern Period. Royal courts moved from residence to residence within their own countries, and the main state institutions and officials moved with them. Subjects would travel to the court to settle routine affairs or to seek justice. Dealing with diplomatic affairs was also affected by mobility. Sovereigns tended to meet in border areas, but seldom visited each other. In 1429, the border town of Lutsk was chosen as a meeting place for a con- ference between the Holy Roman Emperor and the King of Poland and Grand Duke of Lithuania. -

The Curonian Lagoon)

remote sensing Article Remote Sensing of Ice Phenology and Dynamics of Europe’s Largest Coastal Lagoon (The Curonian Lagoon) Rasa Idzelyte˙ 1,*, Igor E. Kozlov 1,2,3 and Georg Umgiesser 1,4 1 Marine Research Institute, Klaipeda University, Universiteto ave. 17, LT-92294 Klaipeda, Lithuania 2 Satellite Oceanography Laboratory, Russian State Hydrometeorological University, Malookhtinsky Prosp., 98, 195196 Saint Petersburg, Russia 3 Natural Sciences Department, Klaipeda University, Herkaus Manto str. 84, LT-92294 Klaipeda, Lithuania 4 ISMAR-CNR, Institute of Marine Sciences, Arsenale—Tesa 104, Castello 2737/F, 30122 Venezia, Italy * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +370-6234-0360 Received: 8 July 2019; Accepted: 30 August 2019; Published: 2 September 2019 Abstract: A first-ever spatially detailed record of ice cover conditions in the Curonian Lagoon (CL), Europe’s largest coastal lagoon located in the southeastern Baltic Sea, is presented. The multi-mission synthetic aperture radar (SAR) measurements acquired in 2002–2017 by Envisat ASAR, RADARSAT-2, Sentinel-1 A/B, and supplemented by the cloud-free moderate imaging spectroradiometer (MODIS) data, are used to document the ice cover properties in the CL. As shown, satellite observations reveal a better performance over in situ records in defining the key stages of ice formation and decay in the CL. Using advantages of both data sources, an updated ice season duration (ISD) record is obtained to adequately describe the ice cover season in the CL. High-resolution ISD maps provide important spatial details of ice growth and decay in the CL. As found, ice cover resides longest in the south-eastern CL and along the eastern coast, including the Nemunas Delta, while the shortest ice season is observed in the northern CL. -

Livestock Farming in the Nemunas River Basin: the Recent Trends and the Impact on the Water Bodies

ISSN 1822-6760. Management theory and studies for rural business and infrastructure development. 2012. Nr. 3 (32). Research papers. LIVESTOCK FARMING IN THE NEMUNAS RIVER BASIN: THE RECENT TRENDS AND THE IMPACT ON THE WATER BODIES Irena Kriščiukaitienė1, Virginia Namiotko1, Tomas Baležentis1, Aliaksandr Pakhomau2 1 Lithuanian Institute of Agrarian Economics 2 Central Research Institute for Complex Use of Water Resources of the Republic of Belarus In accordance with the contemporary sustainable water resources use policy in the European Union, it is important to assess the impact of the agricultural sector – one of the most important sources of pollution – upon the implementation of the objectives stipulated by the Water Frame- work Directive. The research therefore aims at analyzing the influence of the agricultural sector on the pollution of the Nemunas river basin. It was the transboundary pollution that forced the research to cover both Lithuanian and Belorussian territories. The paper analyzes legal aspects of the strate- gic management of water resources, estimates the livestock density and dynamics thereof, and iden- tifies the most polluted territories in Lithuania and Belarus. Research results indicate that more in- tensive animal farming is maintained in the Belarusian part of the Nemunas catchment and has the tendency to increase. At the other end of spectrum, LSU per hectare is two times lower and has the tendency to decrease in Lithuania. Keywords: livestock farming, Nemunas catchment, water pollution. JEL codes: Q530, Q150.