Rural Development and the Restructuring of the Defence Estate: a Preliminary Investigation

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

From the Line in the Sand: Accounts of USAF Company Grade Officers In

~~may-='11 From The Line In The Sand Accounts of USAF Company Grade Officers Support of 1 " 1 " edited by gi Squadron 1 fficer School Air University Press 4/ Alabama 6" March 1994 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data From the line in the sand : accounts of USAF company grade officers in support of Desert Shield/Desert Storm / edited by Michael P. Vriesenga. p. cm. Includes index. 1. Persian Gulf War, 1991-Aerial operations, American . 2. Persian Gulf War, 1991- Personai narratives . 3. United States . Air Force-History-Persian Gulf War, 1991 . I. Vriesenga, Michael P., 1957- DS79 .724.U6F735 1994 94-1322 959.7044'248-dc20 CIP ISBN 1-58566-012-4 First Printing March 1994 Second Printing September 1999 Third Printing March 2001 Disclaimer This publication was produced in the Department of Defense school environment in the interest of academic freedom and the advancement of national defense-related concepts . The views expressed in this publication are those of the authors and do not reflect the official policy or position of the Department of Defense or the United States government. This publication hasbeen reviewed by security andpolicy review authorities and is clearedforpublic release. For Sale by the Superintendent of Documents US Government Printing Office Washington, D.C . 20402 ii 9&1 gook L ar-dicat£a to com#an9 9zacL orflcF-T 1, #ait, /2ZE4Ent, and, E9.#ECLaL6, TatUlLE. -ZEa¢ra anJ9~ 0 .( THIS PAGE INTENTIONALLY LEFT BLANK Contents Essay Page DISCLAIMER .... ... ... .... .... .. ii FOREWORD ...... ..... .. .... .. xi ABOUT THE EDITOR . ..... .. .... xiii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS . ..... .. .... xv INTRODUCTION .... ..... .. .. ... xvii SUPPORT OFFICERS 1 Madzuma, Michael D., and Buoniconti, Michael A. -

Sir Frank Cooper on Air Force Policy in the 1950S & 1960S

The opinions expressed in this publication are those of the authors concerned and are not necessarily those held by the Royal Air Force Historical Society Copyright © Royal Air Force Historical Society, 1993 All rights reserved. 1 Copyright © 1993 by Royal Air Force Historical Society First published in the UK in 1993 All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical including photocopying, recording or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission from the Publisher in writing. Printed by Hastings Printing Company Limited Royal Air Force Historical Society 2 THE PROCEEDINGS OFTHE ROYAL AIR FORCE HISTORICAL SOCIETY Issue No 11 President: Marshal of the Royal Air Force Sir Michael Beetham GCB CBE DFC AFC Committee Chairman: Air Marshal Sir Frederick B Sowrey KCB CBE AFC General Secretary: Group Captain J C Ainsworth CEng MRAeS Membership Secretary: Commander P O Montgomery VRD RNR Treasurer: D Goch Esq FCCA Programme Air Vice-Marshal G P Black CB OBE AFC Sub-Committee: Air Vice-Marshal F D G Clark CBE BA Air Commodore J G Greenhill FBIM T C G James CMG MA *Group Captain I Madelin Air Commodore H A Probert MBE MA Group Captain A R Thompson MBE MPhil BA FBIM MIPM Members: A S Bennell Esq MA BLitt *Dr M A Fopp MA PhD FMA FBIM A E Richardson *Group Captain N E Taylor BSc D H Wood Comp RAeS * Ex-officio The General Secretary Regrettably our General Secretary of five years standing, Mr B R Jutsum, has found it necessary to resign from the post and the committee. -

Recent Military Heritage: a Review of Progress 1994-2004

RECENT MILITARY HERITAGE: A REVIEW OF PROGRESS 1994-2004 A report for Research and Strategy Summary This short report outlines English Heritage’s work on recent military heritage, 1994-2004, focussing on: 1 Commissioned work 2 Internal projects/programmes 3 Advice and influence 4 Management and protection 5 Research agenda 6 European and wider contacts 7 Outreach Much of the commissioned work (s1, below) was undertaken in the period 1994-1999, prior to the creation of English Heritage’s Military and Naval Strategy Group (MNSG) in 1999, and a policy head for military and naval heritage in 2001. Much of what is described in s2-7 (below) was undertaken through the influence and activities of MNSG. A series of annexes provide further details of commissioned work, in-house surveys, publications, conferences and MNSG membership. Review, 1994-2004 1 Commissioned work (Annex 1) Much original research has been commissioned by English Heritage since 1994, largely through its Thematic Listing and Monuments Protection Programmes. This has created a fuller understanding of twentieth century defence heritage than existed previously. For some subjects it contributed to, clarified or expanded upon previous studies (eg. Anti-invasion defences); for others the research was entirely new (eg. Bombing decoys of WWII). Commissioned projects have included: archive-based studies of most major classes of WWII monuments; aerial photographic studies documenting which sites survive; a study of post-medieval fortifications resulting in a set of seven Monument Class Descriptions; studies of aviation and naval heritage, barracks, ordnance yards and a scoping study of drill halls; and characterisation studies of specific key sites (RAF Scampton and the Royal Dockyards at Devonport and Portsmouth). -

Central Lincolnshire Five Year Land Supply Report January 2019 Inc

Central Lincolnshire Five Year Land Supply Report 1 April 2019 to 31 March 2024 (Published January 2019) Contents 1. INTRODUCTION ............................................................................................................ 1 2. POLICY CONTEXT ........................................................................................................ 1 NATIONAL CONTEXT ................................................................................................ 1 THE LOCAL CONTEXT .............................................................................................. 2 3. THE FIVE YEAR REQUIREMENT ................................................................................. 3 PAST COMPLETIONS AND SHORTFALL/SURPLUS ................................................ 3 ADDING BUFFERS .................................................................................................... 5 4. THE FIVE YEAR SUPPLY .............................................................................................. 6 SITES IN THE SUPPLY .............................................................................................. 6 WINDFALL ALLOWANCE .......................................................................................... 7 Small Sites in the Lincoln Urban Area .................................................................. 8 Small Sites in Smaller Settlements and the Rural Area........................................ 8 Other small sites ................................................................................................. -

Y Pwyliaid Yng Nghymru a Lloegr / the Poles in England and Wales

MORAY HIGHLAND ABERDEEN ABERDEENSHIRE CITY ANGUS PERTH AND KINROSS Ddaru heddwch ddim paratoi’r ffordd yn ôl gartref. Peace didn’t pave the way back home. Nie zaznali pokoju, który pozwoliłby im wrócić z powrotem Arhosodd dwyrain Gwlad Pwyl dan feddiannaeth Eastern Poland remained under Soviet do domu. Wschodnia Polska pozostała pod okupacją yr Undeb Sofietaidd. Ni chawson nhw garped occupation. There would be no red carpet sowiecką. Nie mogli spodziewać się powitania z czerwonym coch a dychwelyd gartref yn arwyr rhyfel. Yn for returning Polish war heroes. Instead the dywanem dla powracających polskich bohaterów wojennych. hytrach, caniatawyd y fyddin Bwylaidd a’u hysbytai Polish Army and its military field hospitals Zamiast tego armia polska i jej wojskowe szpitale polowe maes i ddod i Brydain. A’u cartrefi newydd – y were allowed to come to Britain. Their new dostały pozwolenie na przybycie do Wielkiej Brytanii. Ich gwersylloedd a adawyd ar ôl gan Luoedd Arfog yr homes – the camps left behind by the US nowe domy – obozy pozostawione przez amerykańskie i Unol Daleithiau a Chanada. and Canadian armed forces. kanadyjskie siły zbrojne. YR ALBAN Allwedd Key Legenda SCOTLAND NORTHUMBERLAND Gwersyll sefydlu (wedi’i ddewis) Settlement camp (selected) Newcastle Upon Tyne Obozy przesiedleńcze (wybrane) Caerliwelydd TYNE & WEAR Sunderland Ysbyty a gwersyll (wedi’i ddewis) Carlisle Hospital and camp (selected) Szpitale i obozy (wybrane) Ysgolion a cholegau Schools and colleges CUMBRIA DURHAM Szkoły podstawowe i ponadpodstawowe Canolfan awyr a ddefnyddiwyd -

RAF Football Association - E-Bulletin

RAF Football Association - E-Bulletin RAF FA CUP ‘THE KEITH CHRISTIE TROPHY’ AND RAF FA PLATE 19/20 UPDATE With the RAF Cup now in full swing, the second round produced some more exciting ties and saw some big names exit the competition. RAF Leeming’s away trip to Akrotiri was the eagerly anticipated tie of the round, however it proved to be a tough trip for the visitors as they were on the receiving end of a heavy 5-1 defeat. SAC Liam Thornton grabbed four of the goals, taking his overall tally to six and making him the current top scorer in the competition. RAF Brize Norton faced the long journey up to Lossiemouth and it proved to be successful as they ground out a 1-0 win with Sgt Dave Wanless scoring the all-important goal, Brize Norton will be hoping for a slightly shorter journey if they are drawn away in the next round. SAC Liam Wood scored his first two goals of the competition helping RAF Northolt to an away win at Wyton with RAF Coningsby also picking up a convincing away victory running out 4-0 winner against JFC Chicksands & RAF Henlow. RAF Honington who have a great history with the competition were knocked out at the hands of RAF Odiham thanks to a single goal from SAC Clarke Goulding. RAF FA E-Bulletin – RAF Cup Update Elsewhere, RAF Shawbury and RAF Marham both scored four goals each to take them through with victories over MOD St Athan and RAF Waddington respectively. RAF Boulmer also strolled through to the next round with an impressive 7-1 victory over RAF Cranwell. -

Raaf Personnel Serving on Attachment in Royal Air Force Squadrons and Support Units in World War 2 and Missing with No Known G

Cover Design by: 121Creative Lower Ground Floor, Ethos House, 28-36 Ainslie Pl, Canberra ACT 2601 phone. (02) 6243 6012 email. [email protected] www.121creative.com.au Printed by: Kwik Kopy Canberra Lower Ground Floor, Ethos House, 28-36 Ainslie Pl, Canberra ACT 2601 phone. (02) 6243 6066 email. [email protected] www.canberra.kwikkopy.com.au Compilation Alan Storr 2006 The information appearing in this compilation is derived from the collections of the Australian War Memorial and the National Archives of Australia. Author : Alan Storr Alan was born in Melbourne Australia in 1921. He joined the RAAF in October 1941 and served in the Pacific theatre of war. He was an Observer and did a tour of operations with No 7 Squadron RAAF (Beauforts), and later was Flight Navigation Officer of No 201 Flight RAAF (Liberators). He was discharged Flight Lieutenant in February 1946. He has spent most of his Public Service working life in Canberra – first arriving in the National Capital in 1938. He held senior positions in the Department of Air (First Assistant Secretary) and the Department of Defence (Senior Assistant Secretary), and retired from the public service in 1975. He holds a Bachelor of Commerce degree (Melbourne University) and was a graduate of the Australian Staff College, ‘Manyung’, Mt Eliza, Victoria. He has been a volunteer at the Australian War Memorial for 21 years doing research into aircraft relics held at the AWM, and more recently research work into RAAF World War 2 fatalities. He has written and published eight books on RAAF fatalities in the eight RAAF Squadrons serving in RAF Bomber Command in WW2. -

Voices from an Old Warrior Why KC-135 Safety Matters

Voices from an Old Warrior Why KC-135 Safety Matters Foreword by General Paul Selva GALLEON’S LAP PUBLISHING ND 2 EDITION, FIRST PRINTING i Hoctor, Christopher J. B. 1961- Voices from an Old Warrior: Why KC-135 Safety Matters Includes bibliographic references. 1. Military art and science--safety, history 2. Military history 3. Aviation--history 2nd Edition – First Printing January 2014 1st Edition (digital only) December 2013 Printed on the ©Espresso Book Machine, Mizzou Bookstore, Mizzou Publishing, University of Missouri, 911 E. Rollins Columbia, MO 65211, http://www.themizzoustore.com/t-Mizzou-Media-About.aspx Copyright MMXIII Galleon's Lap O'Fallon, IL [email protected] Printer's disclaimer Opinions, conclusions, and recommendations expressed or implied within are solely those of the author. They do not represent the opinions of Mizzou Publishing, or the University of Missouri. Publisher's disclaimer, rights, copying, reprinting, etc Opinions, conclusions, and recommendations expressed or implied within are solely those of the author, except where cited otherwise. They do not represent any U.S. Govt department or agency. This book may be copied or quoted without further permission for non-profit personal use, Air Force safety training, or academic research, with credit to the author and Galleon's Lap. To copy/reprint for any other purpose will require permission. Author's disclaimers Sources can be conflicting, especially initial newspaper reports compared to official information released to the public later. Some names may have a spelling error and I apologize for that. I changed many of the name spellings because I occasionally found more definitive sources written by family members. -

An Aviation Guide Through East Lindsey Locating Active RAF Stations and Former Airfield Sites Contents

An aviation guide through East Lindsey locating active RAF stations and former airfield sites Contents Map To Grimsby Holton Contents Le Clay NORTH COATES N Tetney North Cotes Marshchapel DONNA NOOK MAP NOT DRAWN TO SCALE A1 North 8 Fulstow East Lindsey | East Lindsey Grainsthorpe Thoresby North Somercotes LUDBOROUGH Covenham Reservoir A16 Binbrook Saltfleet A 1031 | East Lindsey Utterby Alvingham KELSTERN North Fotherby Cockerington THEDDLETHORPE A631 Saltfleetby To Market Louth LUDFORD MAGNA Grimoldby St. Peter Theddlethorpe St. Helen Rasen South South Cockerington Elkington Theddlethorpe A157 B1200 MANBY All Saints Mablethorpe Donington Legbourne on Bain Abbreviations North Coates BBMF Visitor Centre A157 Trusthorpe Little Withern Sutton PAGE 4 PAGES 18 & 19 PAGES 30 & 31 A16 Cawthorpe STRUBBYThorpe on Sea Cadwell Woodthorpe East Barkwith Maltby Sandilands MARKET STAINTON le Marsh Introduction Spilsby Lincolnshire Aviation A5 To A Scamblesby 10 Wragby 2 Lincoln Aby PAGE 5 Ruckland 4 PAGES 20 & 21 Heritage Centre A1111 Bilsby Belchford PAGES 32 & 33 A158 Anderby Bardney Strubby Alford Creek Tetford Brinkhill Mumby PAGES 6 & 7 PAGES 22 & 23 Baumber Hemingby Chapel Thorpe Camp Visitor Minting Somersby Mawthorpe St. Leonards A1 Hogsthorpe Centre A 02 West Ashby Bag Enderby Harrington 1 8 Coningsby 6 Woodhall Spa PAGES 34 & 35 Horncastle Willoughby PAGES 8 & 9 Hagworthingham PAGES 24 & 25 BARDNEY Thimbleby Addlethorpe BUCKNALL Partney INGOLDMELLS Horsington B1195 Orby Petwood Hotel Raithby East Kirkby Other Locations Gunby PAGE 36 Stixwould 191 WINTHORPE PAGES 10 & 11 B1 3 SPILSBY Halton 5 MOORBY Hundleby Burgh le Marsh PAGES 26 & 27 Roughton A1 Holegate Old Bolingbroke BURGH ROAD Toynton Great Kelstern The Cottage Museum WOODHALL SPA East Steeping Skegness Coastal Bombing Revesby EASTWe KIRKBYst Keal PAGES 12 & 13 PAGE 37 B1 Thorpe St. -

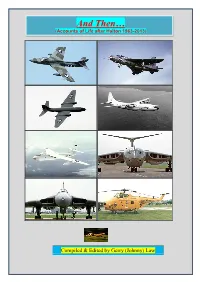

And Then… (Accounts of Life After Halton 1963-2013)

And Then… (Accounts of Life after Halton 1963-2013) Compiled & Edited by Gerry (Johnny) Law And Then… CONTENTS Foreword & Dedication 3 Introduction 3 List of aircraft types 6 Whitehall Cenotaph 249 St George’s 50th Anniversary 249 RAF Halton Apprentices Hymn 251 Low Flying 244 Contributions: John Baldwin 7 Tony Benstead 29 Peter Brown 43 Graham Castle 45 John Crawford 50 Jim Duff 55 Roger Garford 56 Dennis Greenwell 62 Daymon Grewcock 66 Chris Harvey 68 Rob Honnor 76 Merv Kelly 89 Glenn Knight 92 Gerry Law 97 Charlie Lee 123 Chris Lee 126 John Longstaff 143 Alistair Mackie 154 Ivor Maggs 157 David Mawdsley 161 Tony Meston 164 Tony Metcalfe 173 Stuart Meyers 175 Ian Nelson 178 Bruce Owens 193 Geoff Rann 195 Tony Robson 197 Bill Sandiford 202 Gordon Sherratt 206 Mike Snuggs 211 Brian Spence 213 Malcolm Swaisland 215 Colin Woodland 236 John Baldwin’s Ode 246 In Memoriam 252 © the Contributors 2 And Then… FOREWORD & DEDICATION This book is produced as part of the 96th Entry’s celebration of 50 years since Graduation Our motto is “Quam Celerrime (With Greatest Speed)” and our logo is that very epitome of speed, the Cheetah, hence the ‘Spotty Moggy’ on the front page. The book is dedicated to all those who joined the 96th Entry in 1960 and who subsequently went on to serve the Country in many different ways. INTRODUCTION On the 31st July 1963 the 96th Entry marched off Henderson Parade Ground marking the conclusion of 3 years hard graft, interspersed with a few laughs. It also marked the start of our Entry into the big, bold world that was the Royal Air Force at that time. -

Defence Estate Rationalisation Update

MINISTRY OF DEFENCE Defence Estate Rationalisation Update The Minister for the Armed Forces (Andrew Robathan): The Strategic Defence and Security Review (SDSR), announced in October 2010, marked the start of the process of transforming Defence and identified the need for rationalisation of the Defence estate. This included the sale of surplus land and buildings and the delivery of associated running cost reductions. The Army Basing Plan announcement by the Secretary of State on 5 March 2013, enabling the return from Germany and implementation of Army 2020, indicated that there would be a further announcement concerning other changes elsewhere in the Ministry of Defence (MOD) estate across the UK. Today I am providing an update to the House on the results of work to implement the SDSR’s commitments on rationalisation and on unit relocations on the wider Defence estate. Service and civilian personnel at the affected locations will be briefed; we will also engage with the Trades Unions where appropriate. This work will now be taken forward into detailed planning. Lightning II Aircraft Basing at RAF Marham Our first two Lightning II aircraft (Joint Strike Fighter) are currently participating in the US test programme and will remain in the US. We expect to receive frontline aircraft from 2015 onwards with an initial operating capability from land in 2018, followed by first of class flights from HMS Queen Elizabeth later that year. I can now inform the House of the outcome of the further Basing Review recently undertaken in respect of the Lightning II aircraft. Following the SDSR, a number of changes have occurred on the Defence estate that justified a further review of the basing options for Lightning II. -

Ufo-Highlights-Guide-2013.Pdf

Highlights Guide This document contains details of how to navigate through the newly released files. We have included bookmarks in each of the PDF files of key stories and reports highlighted by Dr David Clarke. This will make it easier to navigate through the files. For information on the history of government UFO investigations and where these files fit in please read Dr David Clarke‟s background guide to the files. Navigating the files using the bookmarks To view the bookmarks, click on the „Bookmarks‟ tab on the upper left hand side of the PDF window, the bookmarks tab will expand – as shown below. 1. Click on „Bookmarks‟ tab The „Bookmarks‟ tab will then expand and a list of relevant bookmarks will be displayed – as shown below. 2. Bookmark tab will expand. Clicking on a bookmark will take you to the pages of the file related to that particular story. To see the details of each bookmark – hover over the icon that appears on the top left hand corner of the relevant page of the PDF document – as shown below. 3. Hover or click on bookmark icons to see detail Below is information on the key stories and reports of UFO activity contained in these files. It includes a list of the bookmarks contained in each file, with a short summary of each bookmark. Please note that not all files contain bookmarks. Highlights & Key stories This is the tenth and final tranche of UFO files. There are 25 files containing 4,400 pages. The files cover the work carried out during final two years of the MoD‟s UFO desk, from late 2007 until November 2009.