Vibrating Mail on the Overland Route

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Appendix 1 Documentary Sources for Overland Trails

APPENDIX 1 DOCUMENTARY SOURCES ON OVERLAND TRAILS Prepared by the Mapping and Marking Committee Fifth Edition (Revised and Expanded) June 2014 Published by the Oregon-California Trails Association P.O. Box 1019 Independence, MO 64051-0519 816-252-2276 [email protected] www.octa-trails.org © Copyright 1993,1994,1996,2002, 2014 By Oregon-California Trails Association All Rights Reserved (This page intentionally blank) DOCUMENTARY SOURCES ON OVERLAND TRAILS Emigrant trail literature of all types is the primary documentary resource available to the trail researcher. Fortunately, knowledge of and access to this trail literature is becoming more readily available. For the researcher, it’s a process of identifying and locating desirable emigrant documents, then utilizing them by following the research procedures recommended in the MET Manual. The more knowledge trail researchers have of trail literature, the easier the task and the more effective fieldwork becomes. If detailed enough, emigrant diaries and journals—eyewitness accounts of trails—provide the most reliable documentary evidence for trail research and field verification. A number of standard, published bibliographies on emigrant overland travel are readily available for various emigrant trails. For brevity, only the authors/editors, titles, and publication years are given. On the northern routes see: Merrill J. Mattes, Platte River Road Narratives: A Descriptive Bibliography of Travel Over the Great Central Overland Route to Oregon, California, Utah, Colorado, Montana, and Other Western States and Territories, 1812–1866 (1988). John M. Townley, The Trail West: A Bibliography – Index to Western American Trails, 1841– 1869 (1988). Lannon W. Mintz, The Trail: A Bibliography of the Travelers on the Overland Trail to California, Oregon, Salt Lake City, and Montana during the Years 1841–1864 (1987) Marlin L. -

Wagons, Echo Canyon, Ca. 1868. Courtesy LDS Church Archives. Mormon Emigration Trails Stanley B

Wagons, Echo Canyon, ca. 1868. Courtesy LDS Church Archives. Mormon Emigration Trails Stanley B. Kimball Introduction We are in the midst of an American western trails renaissance. Interest in historic trails has never been higher. There is an annual, quarterly, almost monthly increase in the number of books, guides, bib liographies, articles, associations, societies, conferences, symposia, centers, museums, exhibits, maps, dramatic presentations, videos, fes tivals, field trips, trail-side markers and monuments, grave sites, trail signing, and other ventures devoted to our western trail heritage. 1 In 1968, Congress passed the National Trails System Act and in 1978 added National Historic Trail designations. Since 1971 at least fif teen major federal studies of the Mormon Trail have been made.2 So much is going on that at least half a dozen newsletters must be pub lished to keep trail buffs properly informed. Almost every newsletter records the discovery of new trail ruts and artifacts-for example, the recent discovery of some ruts on the Woodbury Oxbow-Mormon Trail in Butler County, Nebraska, and new excavations regarding the Mor mon occupation of Fort Bridger. Hundreds of trail markers with text, many referring to the Mor mons, line the western trails. These markers have been placed by many federal, state, county, municipal, and private associations, including the Bureau of Land Management; Daughters of the American Revolution; Daughters of Utah Pioneers (who alone have placed more than 465 his torical markers); Sons of Utah Pioneers; Utah Pioneer Trails and Land marks; the Boy Scouts; the Illinois, Iowa, Nebraska, Wyoming, Kansas, New Mexico, Arizona, California, and Utah state historical societies; and many county historical societies. -

National Register of Historic Places Multiple Property Documentation Form

NPS Form 10-900-b OMB No. 1024-0018 United States Department of the Interior National Park Service National Register of Historic Places Multiple Property Documentation Form This form is used for documenting property groups relating to one or several historic contexts. See instructions in National Register Bulletin How to Complete the Multiple Property Documentation Form (formerly 16B). Complete each item by entering the requested information. ___X___ New Submission ________ Amended Submission A. Name of Multiple Property Listing Lincoln Highway – Pioneer Branch, Carson City to Stateline, Nevada B. Associated Historic Contexts (Name each associated historic context, identifying theme, geographical area, and chronological period for each.) Early Trails and Overland Routes, 1840’s-1863 Early Road Development in Nevada, 1865-1920’s Establishment of the Lincoln Highway and the Pioneer Branch, 1910-1913 Evolution of the Lincoln Highway and the Pioneer Branch, 1914-1957 C. Form Prepared by: name/title Chad Moffett, Dianna Litvak, Liz Boyer, Timothy Smith organization Mead & Hunt, Inc. street & number 180 Promenade Circle, Suite 240 city or town Sacramento state CA zip code 95834 e-mail [email protected] telephone 916-971-3961 date January 2018 D. Certification As the designated authority under the National Historic Preservation Act of 1966, as amended, I hereby certify that this documentation form meets the National Register documentation standards and sets forth requirements for the listing of related properties consistent with the National Register criteria. This submission meets the procedural and professional requirements set forth in 36 CFR 60 and the Secretary of the Interior’s Standards and Guidelines for Archeology and Historic Preservation. -

New Horizons on the Oregon Trail

Nebraska History posts materials online for your personal use. Please remember that the contents of Nebraska History are copyrighted by the Nebraska State Historical Society (except for materials credited to other institutions). The NSHS retains its copyrights even to materials it posts on the web. For permission to re-use materials or for photo ordering information, please see: http://www.nebraskahistory.org/magazine/permission.htm Nebraska State Historical Society members receive four issues of Nebraska History and four issues of Nebraska History News annually. For membership information, see: http://nebraskahistory.org/admin/members/index.htm Article Title: New Horizons on the Oregon Trail Full Citation: Merrill J Mattes, “New Horizons on the Oregon Trail,” Nebraska History 56 (1975): 555-571. URL of article: http://www.nebraskahistory.org/publish/publicat/history/full-text/NH1975OldOregonTrail.pdf Date: 3/30/2016 Article Summary: This article presents the address given by Merrill J Mattes before the Nebraska State Historical Society at Lexington, Nebraska, June 14, 1975. It is primarily a descriptive of the first Bicentennial celebration at Lexington and Concord, Massachusetts, in April of 1975 and a journey along the Oregon Trail that the presenter had taken. Cataloging Information: Photographs / Images: Merrill J Mattes receiving the 1969 Western Heritage Award in the nonfiction category for his The Great Platte River Road. NEW HORIZONS ON mE OLD OREGON TRAIL By MERRILL J. MATTES Presented at the Spring Meeting of the Nebraska State Historical Society at Lexington, Nebraska, June 14, 1975 This spring meeting of the Nebraska State Historical Society at Lexington is a very special occasion, and I hope my remarks will convey to you why I consider this a red-letter day. -

The Story of Mud Springs

The Story of Mud Springs (Article begins on page 2 below.) This article is copyrighted by History Nebraska (formerly the Nebraska State Historical Society). You may download it for your personal use. For permission to re-use materials, or for photo ordering information, see: https://history.nebraska.gov/publications/re-use-nshs-materials Learn more about Nebraska History (and search articles) here: https://history.nebraska.gov/publications/nebraska-history-magazine History Nebraska members receive four issues of Nebraska History annually: https://history.nebraska.gov/get-involved/membership Full Citation: Paul Henderson, “The Story of Mud Springs,” Nebraska History 32 (1951): 108-119 Article Summary: The Scherers, early settlers in western Nebraska, purchased in 1896 the land on which the town of Mud Springs and the site of the old Pony Express station are situated. Once a place of refuge from hostile Indians, the property became an outstanding ranch noted for its hospitality. Cataloging Information: Names: F T Bryan, Thomas Montgomery, William O Collins, William Ellsworth, Mr and Mrs J N Scherer Nebraska Place Names: Mud Springs, Morrill County Keywords: covered wagons, stage coaches, Pony Express, trans-continental telegraph line, Central Overland Route, Ash Hollow, Twenty-Two Mile Ranch, Rouilette & Pringle’s Ranch, McArdle’s Ranch, Jules Ranch (later Julesberg), Union Pacific Railroad Photographs / Images: Mud Springs area map, ground plan and location map of Mud Springs THE STORY OF MUD SPRINGS BY PAUL HENDERSON un Springs, because of the events which took place there in the days of the Covered Wagon Emigration, M has become one of the many "story spots" that dot the way along the old Oregon-California wagon road, a trail that has become almost obliterated except in the non agricultural area of the West. -

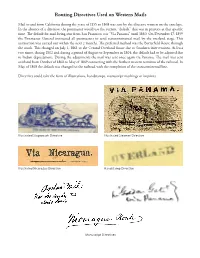

Routing Directives Used on Western Mails

Routing Directives Used on Western Mails Mail to and from California during the years of 1855 to 1868 was sent by the directive written on the envelope. In the absence of a directive, the postmaster would use the current “default” that was in practice at that specific time. The default for mail being sent from San Francisco was “Via Panama” until 1860. On December 17, 1859 the Postmaster General instructed all postmasters to send transcontinental mail by the overland stage. This instruction was carried out within the next 2 months. The preferred method was the Butterfield Route through the south. This changed on July 1, 1861 to the Central Overland Route due to Southern interventions. At least two times, during 1862 and during a period of August to September in 1864, the default had to be adjusted due to Indian depredations. During the adjustments the mail was sent once again via Panama. The mail was sent overland from October of 1868 to May of 1869 connecting with the farthest western terminus of the railroad. In May of 1869 the default was changed to the railroad with the completion of the transcontinental line. Directives could take the form of illustrations, handstamps, manuscript markings or imprints. Illustrated Stagecoach Directive Illustrated Steamer Directive Illustrated Nicaragua Directive Handstamp Directive Manuscript Directives Via Panama - Directives Mail was carried by the US Mail Steamship Co. (between NY and Chagres) and the Pacific Mail Steamship Co (between Panama and San Francisco). Carriage across the isthmus of Panama was by railroad. This was the default method of mail carriage until December 17, 1859. -

Utah Mail Service Before the Coming of the Railroad, 1869

Brigham Young University BYU ScholarsArchive Theses and Dissertations 1957 Utah Mail Service Before the Coming of the Railroad, 1869 Ralph L. McBride Brigham Young University - Provo Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/etd Part of the History Commons, and the Mormon Studies Commons BYU ScholarsArchive Citation McBride, Ralph L., "Utah Mail Service Before the Coming of the Railroad, 1869" (1957). Theses and Dissertations. 4921. https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/etd/4921 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by BYU ScholarsArchive. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of BYU ScholarsArchive. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. UTAH MAIL SERVICE EFOREBEFOREB THE COMING OF vitthevicTHS RAILROAD 1869 A ttiftistheftsthefisSUBMITTEDSUWATTTED TO THE department OF HISTORY OF BRIGHAMBRIGITAM YOUNG LVuniversityI1RSIT Y INZT 13 PARTIAL fulfillment ortheOFTHEOF THE requirementsrequimrequam1 L mentsWENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF FASTERMASTER orOF ARTS by ralph L mcbride 1957 00oo i acknowledgements sincere appreciation is extended to many for their help in the preparation of this thesis special gratitude is extended to dr leroy hafen for whom I1 hold great esteem my committee chairman for his valuable assistance and helpful attitude dr briant jacobs committee member is given acknowledgement for his inspiration and guidance the cooperation and assistance of the library staffs of the erigBrigbrighamhenahevahavayoung -

February 9, 2015)

Contact: Megan van Frank, 801.359.9670 ext. 110 [email protected] Photos Available Upon Request For Immediate Release (February 9, 2015) Beehive Archive Welcome to the Beehive Archive—your weekly bite-sized look at some of the most pivotal—and peculiar—events in Utah history. With all of the history and none of the dust, the Beehive Archive is a fun way to catch up on Utah’s past. Beehive Archive is a production of the Utah Humanities Council, provided to local papers as a weekly feature article focusing on Utah history topics drawn from our award-winning radio series, which can be heard each week on KCPW and Utah Public Radio. To Utah By Stagecoach The stagecoach is a legendary symbol of the American West, part of a transportation network that spanned the continent. How did Utah fit into this network? Traveling to Utah was difficult – to say the least – in the mid-19th Century. Major land routes between the east and west coasts skirted Utah to the north and south. The need for easier communication between Salt Lake City and the outside world drove the development of new transportation routes for both mail and passengers. The first such stagecoach service was started in 1858 by George Chorpenning using the Central Overland Route, a new trail that ran through central Utah and Nevada to California. The route was originally scouted in 1855 by Howard Egan, who used it to drive cattle, and was improved by US Army Captain James Simpson, who used it to supply Camp Floyd during the Utah War. -

Bald Mountain Mine North and South Operations Area Projects Draft EIS 3.1 – Introduction 3.1-1

Bald Mountain Mine North and South Operations Area Projects Draft EIS 3.1 – Introduction 3.1-1 3.0 Affected Environment and Environmental Consequences 3.1 Introduction This chapter describes the affected environment and environmental consequences on the affected environment from the Proposed Action and the alternatives. The baseline information used to describe the affected environment was obtained from published and unpublished materials; interviews with local, state, and federal agencies; and from field and laboratory studies conducted in the study area. The affected environment for individual resources was delineated based on the area of potential direct and indirect environmental impacts for the proposed NOA and SOA projects. For resources such as soils and vegetation, the study area was determined to be the physical location and immediate vicinity of the areas of proposed expanded and new disturbance associated with the proposed NOA and SOA projects. For other resources such as water quality, air quality, wildlife, social and economic values, and the transport of hazardous materials, the affected environment was more extensive (e.g., airshed, local communities, etc.). The environmental consequences analysis in this chapter includes both the direct and indirect impacts of the Proposed Action and the alternatives, as well as potential cumulative project impacts when considered with other non-related actions affecting the same resources. The analysis of potential direct and indirect impacts from the Proposed Action assumed the implementation of design features and ACEPMs (Section 2.4.3, Design Features and Applicant-committed Environmental Protection Measures for the Proposed North and South Operations Area Projects). Additionally, proposed monitoring and mitigation measures developed in response to anticipated impacts are recommended by the BLM for individual resources, as discussed at the end of each resource section. -

(Central Overland) Route

1861 Placerville to Missouri (Central Overland) Route On March 12, 1861 a contract for overland mail service, via the central route as then in use by the Pony Express, was awarded to the Overland Mail Company (OMC). The contract for route #10,773 called for letter mail service six days a week, with additional mail matter to be carried on a weight-available basis. The new service schedule commenced on July 1, 1861 with mail departures from Placerville, California and Saint Joseph, Missouri. In September 1861 the eastern terminal was changed to Atchison, Kansas. Branch service to Denver was inaugurated, and the first direct contract mail from Santa Fe to Denver arrived. The OMC divided the operational control of the route. The Central Overland & Pikes Peak Express (COC&PP) handled the mails east of Salt Lake City, and Wells, Fargo and Company handled the mails west of Salt Lake City. Ben Holladay purchased the COC&PP on March 21, 1862 and renamed it the Overland Stage Company. In July 1862, following Indian depredations, the post office ordered the OMC to relocate the section of the route between Ft. Bridger and Julesburg to the Cherokee Trail south of Fort Laramie. Indian troubles in this area forced closure of the new route for much of August and September 1862 and for short periods in 1863. In 1864, additional Indian troubles closed the route for a longer period in August and September and service was not normalized through Julesburg until March 2, 1865. During the most severe of these disruptions mail from New York and San Francisco was diverted to the Via Panama route until the route was able to be safely re-opened. -

National Register of Historic Places Registration Form

NPS Form 10-900 OMB No. 1024-0018 (Expires 5/31/2012) United States Department of the Interior National Park Service National Register of Historic Places Registration Form This form is for use in nominating or requesting determinations for individual properties and districts. See instructions in National Register Bulletin, How to Complete the National Register of Historic Places Registration Form. If any item does not apply to the property being documented, enter "N/A" for "not applicable." For functions, architectural classification, materials, and areas of significance, enter only categories and subcategories from the instructions. Place additional certification comments, entries, and narrative items on continuation sheets if needed (NPS Form 10-900a). 1. Name of Property historic name West Side Historic District other names/site number 2. Location street & number Roughly bounded by Curry, Mountain, Fifth, and John streets not for publication city or town Carson City vicinity state Nevada code NV county Carson City code 510 3. State/Federal Agency Certification As the designated authority under the National Historic Preservation Act, as amended, I hereby certify that this X nomination _ request for determination of eligibility meets the documentation standards for registering properties in the National Register of Historic Places and meets the procedural and professional requirements set forth in 36 CFR Part 60. In my opinion, the property _ meets _ does not meet the National Register Criteria. I recommend that this property be considered significant at the following level(s) of significance: national X statewide local ____________________________________ Signature of certifying official Date _____________________________________ Title State or Federal agency/bureau or Tribal Government In my opinion, the property meets does not meet the National Register criteria. -

The Southern Overland Mail and Stagecoach Line, 1857-1861

New Mexico Historical Review Volume 32 Number 2 Article 3 4-1-1957 The Southern Overland Mail and Stagecoach Line, 1857-1861 Oscar Osburn Winther Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalrepository.unm.edu/nmhr Recommended Citation Winther, Oscar Osburn. "The Southern Overland Mail and Stagecoach Line, 1857-1861." New Mexico Historical Review 32, 2 (1957). https://digitalrepository.unm.edu/nmhr/vol32/iss2/3 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by UNM Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in New Mexico Historical Review by an authorized editor of UNM Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected], [email protected]. PORTSMOUTH SQUARE, SAN FRANCISCO Departure of the first Butterfield Overland Mail NEW MEXICO HISTORICAL REVIEW VOL XXXII APRIL, 1957 No.2 THE SOUTHERN OVERLAND MAIL AND STAGECOACH LINE, 1857-1861. By OSCAR OSBURN WINTHER HE MASSIVE westward migration following the discovery T of gold in California and the Mexican Cession in 1848 produced, in its wake, a crying demapd for adequate com munication between the old East and the new West. There were high hopes that' a ,raih;oad would someday span the continent, but meanwhile the West demanded regular mail and stagecoach services between the then existing rail ter minals on the banks ofthe Mississippi River and the distant shores of the Pacific Ocean. Prior to 1848 only the most limited, casual, and cumbersome of transportational facilities existed in this area, and these were deemed hopelessly inade quate in meeting the requirements, not only of pivotal Cali fornia but of other western communities as well.