Qt7z55j01t.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Why Do Bridging Veins Rupture Into the Virtual Subdural Space?

J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry: first published as 10.1136/jnnp.47.2.121 on 1 February 1984. Downloaded from Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery, and Psychiatry 1984;47:121-127 Why do bridging veins rupture into the virtual subdural space? T YAMASHIMA, RL FRIEDE From the Department ofNeuropathology, University of Gottingen, Gottingen, Federal Republic of Germany SUMMARY Electron microscopic data on human bridging veins show thin walls of variable thick- ness, circumferential arrangement of collagen fibres and a lack of outer reinforcement by arach- noid trabecules, all contributory to the subdural portion of the vein being more fragile than its subarachnoid portion. These features explain the laceration of veins and the subdural location of resultant haematomas. Most subdural haematomas due to venous bleeding walls are delicate, lacking muscle fibres, with only a have been attributed to lacerations in bridging veins. thin fibrous wall and a thin elastic lamina adjacent to These veins form short trunks passing directly from the endothelial layer. The conclusions of these two the brain to the dura mater, almost at right angles to authors, have gained wide acceptance, although guest. Protected by copyright. both. Between these two points, bridging veins take there was little evidence concerning the fragility of a straight course with no tortuosity to allow for the the vein walls. possible displacement of brain.' Trotter2 speculated The purpose of the present communication is to that subdural haematomas are invariably due to provide electron microscopic data on tissue fixed in trauma tearing large veins, an interpretation situ, which might throw some light on to the lacera- elaborated by Krauland.3 According to Leary,4 the tion mechanism of bridging veins and its relationship common sources of subdural haematomas are rup- to the development of subdural haematoma. -

Gross Anatomy

www.BookOfLinks.com THE BIG PICTURE GROSS ANATOMY www.BookOfLinks.com Notice Medicine is an ever-changing science. As new research and clinical experience broaden our knowledge, changes in treatment and drug therapy are required. The authors and the publisher of this work have checked with sources believed to be reliable in their efforts to provide information that is complete and generally in accord with the standards accepted at the time of publication. However, in view of the possibility of human error or changes in medical sciences, neither the authors nor the publisher nor any other party who has been involved in the preparation or publication of this work warrants that the information contained herein is in every respect accurate or complete, and they disclaim all responsibility for any errors or omissions or for the results obtained from use of the information contained in this work. Readers are encouraged to confirm the infor- mation contained herein with other sources. For example and in particular, readers are advised to check the product information sheet included in the package of each drug they plan to administer to be certain that the information contained in this work is accurate and that changes have not been made in the recommended dose or in the contraindications for administration. This recommendation is of particular importance in connection with new or infrequently used drugs. www.BookOfLinks.com THE BIG PICTURE GROSS ANATOMY David A. Morton, PhD Associate Professor Anatomy Director Department of Neurobiology and Anatomy University of Utah School of Medicine Salt Lake City, Utah K. Bo Foreman, PhD, PT Assistant Professor Anatomy Director University of Utah College of Health Salt Lake City, Utah Kurt H. -

Dynamic Assessment of Venous Anatomy and Function in Neurosurgery with Real-Time Intraoperative Multimodal Ultrasound: Technical Note

NEUROSURGICAL FOCUS Neurosurg Focus 45 (1):E6, 2018 Dynamic assessment of venous anatomy and function in neurosurgery with real-time intraoperative multimodal ultrasound: technical note Francesco Prada, MD,1,2 Massimiliano Del Bene, MD,1,3 Giovanni Mauri, MD,4 Massimo Lamperti, MD,5 Davide Vailati, MD,6 Carla Richetta, MD,7 Marco Saini, MD,1 Davide Santuari, MD,8 M. Yashar S. Kalani, MD, PhD,2 and Francesco DiMeco, MD1,9 1Department of Neurosurgery, Fondazione IRCCS Istituto Neurologico C. Besta, Milan, Italy; 2Department of Neurological Surgery, University of Virginia Health Science Center, Charlottesville, Virginia; Departments of 3Experimental Oncology and 4Radiology, European Institute of Oncology, Milan, Italy; 5Anesthesiology Unit, Cleveland Clinic, Abu Dhabi, United Arab Emirates; 6Anesthesiology Unit, Ospedale di Circolo di Melegnano, Presidio di Vizzolo Predabissi, Milan, Italy; 7Department of Neurosurgery, Sourasky Medical Center, Tel Aviv, Israel; 8Department of Vascular Surgery, Ospedale S. Carlo, Milan, Italy; and 9Department of Neurological Surgery, Johns Hopkins Medical School, Baltimore, Maryland The relevance of the cerebral venous system is often underestimated during neurosurgical procedures. Damage to this draining system can have catastrophic implications for the patient. Surgical decision-making and planning must consider each component of the venous compartment, from the medullary draining vein to the dural sinuses and extracranial veins. Intraoperative ultrasound (ioUS) permits the real-time study of venous compartments using different modalities, thus allowing complete characterization of their anatomical and functional features. The B-mode (brightness mode) offers a high-resolution anatomical representation of veins and their relationships with lesions. Doppler modalities (color, power, spectral) allow the study of blood flow and identification of vessels to distinguish their functional characteristics. -

Dural Venous Channels: Hidden in Plain Sight–Reassessment of an Under-Recognized Entity

Published July 16, 2020 as 10.3174/ajnr.A6647 ORIGINAL RESEARCH INTERVENTIONAL Dural Venous Channels: Hidden in Plain Sight–Reassessment of an Under-Recognized Entity M. Shapiro, K. Srivatanakul, E. Raz, M. Litao, E. Nossek, and P.K. Nelson ABSTRACT BACKGROUND AND PURPOSE: Tentorial sinus venous channels within the tentorium cerebelli connecting various cerebellar and su- pratentorial veins, as well as the basal vein, to adjacent venous sinuses are a well-recognized entity. Also well-known are “dural lakes” at the vertex. However, the presence of similar channels in the supratentorial dura, serving as recipients of the Labbe, super- ficial temporal, and lateral and medial parieto-occipital veins, among others, appears to be underappreciated. Also under-recog- nized is the possible role of these channels in the angioarchitecture of certain high-grade dural fistulas. MATERIALS AND METHODS: A retrospective review of 100 consecutive angiographic studies was performed following identification of index cases to gather data on the angiographic and cross-sectional appearance, location, length, and other features. A review of 100 consecutive dural fistulas was also performed to identify those not directly involving a venous sinus. RESULTS: Supratentorial dural venous channels were found in 26% of angiograms. They have the same appearance as those in the tentorium cerebelli, a flattened, ovalized morphology owing to their course between 2 layers of the dura, in contradistinction to a rounded cross-section of cortical and bridging veins. They are best appreciated on angiography and volumetric postcontrast T1- weighted images. Ten dural fistulas not directly involving a venous sinus were identified, 6 tentorium cerebelli and 4 supratentorial. -

Anatomic Comparison of Veins of Labbé Between Autopsy, Digital Subtraction Angiography and Computed Tomographic Venography

Fang et al. BioMed Eng OnLine (2017) 16:84 DOI 10.1186/s12938-017-0374-3 BioMedical Engineering OnLine RESEARCH Open Access Anatomic comparison of veins of Labbé between autopsy, digital subtraction angiography and computed tomographic venography Qiong Fang1, Anhong Jiang2, Wei Tao3* and Lin Xin4 *Correspondence: [email protected] Abstract 3 Department of Anatomy, Objective: The drainage portion of the vein of Labbé varies, and it is difcult to pre- School of Medicine, Anhui University of Science & dict whether the operation is likely to damage this vein. The aim of this study was to Technology, 25 Dongshan correlate the microanatomy of the vein of Labbé with digital subtraction angiography Road, Huainan 232001, China (DSA) and computed tomographic venography (CTV), in order to provide a basis for Full list of author information is available at the end of the the preservation of the vein of Labbé during a supratentorial surgical approach. article Methods: A total of 30 human cadavers (60 sides) and 61 living patients (110 sides) were examined in this study. Each cadaver head was injected with blue latex via the superior sagittal sinus and the internal jugular veins. The venograms of each patient were obtained from the venous phases of DSA (60 sides for 36 patients) or CTV (50 sides for 25 patients). Results: The patients were divided into four subgroups based on the location where a vein entered the dural sinus: the transverse sinus group, the tentorial group, the petrosal group, and the upper-transverse sinus group. The veins of Labbé in transverse sinus group and petrosal group directly entered dural sinus. -

Structural and Mechanical Characterisation of Bridging Veins: a Review

Structural and mechanical characterisation of bridging veins: a review Nele Famaeya,∗, Zhao Ying Cuia,∗, Grace Umuhire Musigazib, Jan Ivensc, Bart Depreitereb, Erik Verbekend, Jos Vander Slotena aBiomechanics Section, KU Leuven, Belgium bDepartment of Neurosurgery, University Hospital Gasthuisberg, KU Leuven, Belgium cComposite Materials Group, Department of Metallurgy and Materials Engineering, KU Leuven, Belgium dTranslational Cell & Tissue Research, KU Leuven, Belgium Abstract Bridging veins drain the venous blood from the cerebral cortex into the supe- rior sagittal sinus (SSS) and doing so they bridge the subdural space. Despite their importance in head impact biomechanics, little is known about their properties with respect to histology, morphology and mechanical behaviour. Knowledge of these characteristics is essential for creating a biofidelic finite element model to study the biomechanics of head impact, ultimately leading to the improved design of protective devices by setting up tolerance criteria. This paper presents a comprehensive review of the state-of-the-art knowledge on bridging veins. Tolerance criteria to prevent head injury through impact have been set by a number of research groups, either directly through impact experiments or by means of finite element (FE) simulations. Current state-of-the-art FE head models still lack a biofidelic representation of the bridging veins. To achieve this, a thorough insight into their nature and behaviour is re- quired. Therefore, an overview of the general morphology and histology is provided here, showing the clearly heterogeneous nature of the bridging vein complex, with its three different layers and distinct morphological and histo- logical changes at the region of outflow into the superior sagittal sinus. -

The Cerebral Venous Anatomy & Management Of

THE CEREBRAL VENOUS ANATOMY & MANAGEMENT OF POSTOPERATIVE VENOUS INFARCT Cerebral venous system : Gross anatomy C.V Drainage comprises of 3 segments: • 1. outer/superficial segment:-drains scalp/ muscles/tendons by scalp veins. • 2. intermediate segment:-draining skull/ diploe/duramater by diploe veins, emissary veins, meningeal veins & dural venous sinuses. • 3. cerebral segment:-draining the brain proper by means of superficial cortical veins & deep venous system. Cerebral venous system : Gross anatomy • Scalp veins: • Diploic veins: The diploic veins & scalp veins can function as collateral pathways for venous outflow from I/C structures. • Emissary veins: • The meningeal veins: • The bridging veins: Cerebral venous system : Gross anatomy Cortical Veins – The superficial cortical veins are divided into three group based on whether they drain the lateral, medial, or inferior surface of the hemisphere – The cortical veins on the three surfaces are further subdivided on the basis of the lobe and cortical area that they drain. – The largest group of cortical veins terminate by exiting the subarachnoid space to become bridging veins that cross the subdural space and empty into the venous sinuses in the dura mater. – A smaller group of cortical veins terminate by directly joining the deep venous system of the brain Dural sinuses and bridging veins. • The bridging veins are divided into four groups based on their site of termination: • a superior sagittal group (dark blue), which drains into the superior sagittal sinus; • a tentorial group (green), which drains into the transverse or lateral tentorial sinus; • a sphenoidal group (red), which drains into the sphenoparietal or cavernous sinus; and • a falcine group (purple), which drains into the straight or inferior sagittal sinus either directly or through the basal, great, or internal cerebral veins. -

School of Biomedical Sciences, and the Faculty of Medicine and Health Sciences for My Phd Studentship at the University of Nottingham

Detailed Structure of the Venous Drainage of the Brain: Relevance to Accidental and Non-Accidental Traumatic Head Injuries Seneka Nakagawa, BMedSci Thesis submitted to the University of Nottingham for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy March 2014 Contents Contents ...................................................................................................... i Abstract ................................................................................................... viii Conferences and Peer-reviewed Publications ................................................... ix Acknowledgements ....................................................................................... x List of Definitions and Abbreviations ............................................................... xi List of Figures ........................................................................................... xiv List of Tables ............................................................................................xxiv Chapter 1. Introduction and Literature Review ................................................ 1 1.1. Background ..................................................................................... 1 1.2. Summary of Anatomy of the Meninges and Venous System ............ 2 1.3. Introduction to NAHI and SBS ......................................................... 9 1.4. Introduction to Hypotheses and Theories regarding SDH in NAHI .. 10 1.4.1. Rotational Acceleration of the Head causing Bridging Vein Rupture ............................................................................................. -

Mechanical and Structural Characterisation of the Dural Venous Sinuses Darragh R

www.nature.com/scientificreports OPEN Mechanical and structural characterisation of the dural venous sinuses Darragh R. Walsh1,2, James J. Lynch1,2, David T. O’ Connor1,2,3, David T. Newport1,2 & John J. E. Mulvihill1,2,3* The dural venous sinuses play an integral role in draining venous blood from the cranial cavity. As a result of the sinuses anatomical location, they are of signifcant importance when evaluating the mechanopathology of traumatic brain injury (TBI). Despite the importance of the dural venous sinuses in normal neurophysiology, no mechanical analyses have been conducted on the tissues. In this study, we conduct mechanical and structural analysis on porcine dural venous sinus tissue to help elucidate the tissues’ function in healthy and diseased conditions. With longitudinal elastic moduli values ranging from 33 to 58 MPa, we demonstrate that the sinuses exhibit higher mechanical stifness than that of native dural tissue, which may be of interest to the feld of TBI modelling. Furthermore, by employing histological staining and a colour deconvolution protocol, we show that the sinuses have a collagen-dominant extracellular matrix, with collagen area fractions ranging from 84 to 94%, which likely explains the tissue’s large mechanical stifness. In summary, we provide the frst investigation of the dural venous sinus mechanical behaviour with accompanying structural analysis, which may aid in understanding TBI mechanopathology. Te dural venous sinuses are large venous conduits within the dura mater layer of the meninges that are respon- sible for draining virtually all of the venous blood from the cerebral hemispheres 1. Tus, their injury or acute occlusion can lead to signifcant clinical complications2 and is considered a life-threatening injury3. -

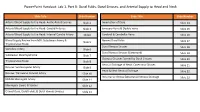

Powerpoint Handout: Lab 1, Part B: Dural Folds, Dural Sinuses, and Arterial Supply to Head and Neck

PowerPoint Handout: Lab 1, Part B: Dural Folds, Dural Sinuses, and Arterial Supply to Head and Neck Slide Title Slide Number Slide Title Slide Number Arterial Blood Supply to the Head: Aortic Arch Branches Slide 2 Innervation of Dura Slide 14 Arterial Blood Supply to the Head: Carotid Arteries Slide 3 Emissary Veins & Diploic Veins Slide 15 Arterial Blood Supply to the Head: Internal Carotid Artery Slide4 Cerebral & Cerebellar Veins Slide 16 Blood Supply Review from MSI: Subclavian Artery & Named Dural Folds Slide 5 Slide 17 Thyrocervical Trunk Dural Venous Sinuses Slide 18 Vertebral Artery Slide 6 Dural Venous Sinuses (Continued) Slide 19 Subclavian Steal Syndrome Slide 7 Osseous Grooves formed by Dural Sinuses Slide 20 Thyrocervical Trunk Slide 8 Venous Drainage of Head: Cavernous Sinuses Slide 21 Review: Suprascapular Artery Slide 9 Head & Neck Venous Drainage Slide 22 Review: Transverse Cervical Artery Slide 10 Intracranial Versus EXtracranial Venous Drainage Slide 23 Middle Meningeal Artery Slide 11 Meningeal Layers & Spaces Slide 12 Cranial Dura, Dural Folds, & Dural Venous Sinuses Slide 13 Arterial Blood Supply to the Head: Aortic Arch Branches The head and neck receive their blood supply from https://3d4medic.al/PXGmbxEt branches of the right and left common carotid and right and left subclavian arteries. • On the right side, the subclavian and common carotid arteries arise from the brachiocephalic trunk. • On the left side, these two arteries originate from the arch of the aorta. Arterial Blood Supply to the Head: Carotid Arteries On each side of the neck, the common carotid arteries ascend in the neck to the upper border of the thyroid cartilage (vertebral level C3/C4) where they divide into eXternal and internal carotid arteries at the carotid bifurcation. -

Natural History and Classification of Davf Second Case: SHA 1 2 3 4

04.11.2019 • 63 yo • SHA • VII cn paresis , • Orbital pain • Dizziness Natural history and Salvatore Mangiafico Interventional Nurovascular unit classification of dAVF Careggi University Hospital Florence 12 34 second case: SHA 56 04.11.2019 Third Case: seizure 78 a problem is always made of several questions and its solution is always to anwser to each one of them • Is it a A‐V malformation ? • May this A‐V shunt explain the clincal presentation? the problem is how to treat it ? • Wich is its possible evolution ? • Where the A‐V shunt is it • Wich way to follow to occlude it ? 910 Dural Arterior Venous Fistulas (DAVF) are acquaided vascular «malformations» DAVF account for approximately 10–15% of all intracranial with un unknown aetiology or secondary vascular malformations due to trhombophilic state, phlogistitic or traumatic process in wich multiple 0.16 per 100 000 per year approximately 12.5%of all arteriovenous shunts develop inside dural intracranial AVMs vascular stuctures without the interposition of a malformative nidus. the mean age of presentation is between 50 and 60 years. DAVF are almost exclusively supplied by meningeal arteries arising from esternal , in Japan 0,29 a 100.000 su 1815 casi Acta Neuroch Suppl 2016 internal carotid and vertebral arteries and rarely from intracranial pial branches Venous drainage can be formed between dural sinus, cortical veins or both 11 12 04.11.2019 Etiopathogenesis : Neo vascularization and venous 3 theories Menigeal arteries have no connection dilatation are induced by an with the sinus and cortical veins (BV) inflammatory process 1)venous sinus occlusion precedes and is 2)DAVFs arise from naturally occurring dormant directly responsible for development of the channels between dural arteries and sinuses, which fistula. -

Anatomy and Development of the Meninges: Implications for Subdural Collections and CSF Circulation

Pediatr Radiol (2009) 39:200–210 DOI 10.1007/s00247-008-1084-6 THEORETICAL CONSIDERATIONS Anatomy and development of the meninges: implications for subdural collections and CSF circulation Julie Mack & Waney Squier & James T. Eastman Received: 27 May 2008 /Revised: 4 November 2008 /Accepted: 17 November 2008 / Published online: 23 January 2009 # Springer-Verlag 2009 Abstract The dura is traditionally viewed as a supportive Introduction fibrous covering of the brain containing the dural venous sinuses but otherwise devoid of vessels and lacking any Infantile subdural hemorrhage (SDH) is often traumatic, specific function. However, review of the embryology and and ruptured bridging veins are thought to be the source of anatomy reveals the dura to be a complex, vascularized and subdural blood in traumatic conditions. However, infantile innervated structure, not a simple fibrous covering. The dura SDH occurs in a number of conditions in which there is no contains an inner vascular plexus that is larger in the infant evidence of mechanical trauma. SDH without trauma has than in the adult, and this plexus likely plays a role in CSF been reported in benign extracerebral fluid collections, a absorption. This role could be particularly important in the condition characterized by macrocephaly and increased infant whose arachnoid granulations are not completely cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) in the subarachnoid space as well developed. Although subdural hemorrhage is frequently as in glutaric aciduria type 1, a metabolic disease associated traumatic, there are nontraumatic conditions associated with with macrocephaly and large extraaxial CSF collections [1– subdural hemorrhage, and the inner dural plexus is a likely 7].