Chapter XII Embassy Tokyo Response to Japan's March 11 Triple

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Resilient Infrastructure Ppps 15 1.3 Scope and Objectives of This Study 19 1.4 Selection of Cases for the Japan Case Study 20 1.5 Structure of This Report 21

Resilient Infrastructure Public-Private Partnerships (PPPs): Contracts and Procurement Contracts Public-Private Infrastructure Partnerships (PPPs): Resilient Resilient Infrastructure Public Disclosure Authorized Public-Private Partnerships (PPPs): Contracts and Procurement Public Disclosure Authorized The Case of Japan The Case of Japan The Case Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized ©2017 The World Bank International Bank for Reconstruction and Development The World Bank Group 1818 H Street NW, Washington, DC 20433 USA December 2017 DISCLAIMER This work is a product of the staff of The World Bank with external contributions. The findings, interpretations, and conclusions expressed in this work do not necessarily reflect the views of The World Bank, its Board of Executive Directors, or the governments they represent. The World Bank does not guarantee the accuracy of the data included in this work. The boundaries, colors, denominations, and other information shown on any map in this work do not imply any judgment on the part of The World Bank concerning the legal status of any territory or the endorsement or acceptance of such boundaries. Nothing herein shall constitute or be considered to be a limitation upon or waiver of the privileges and immunities of The World Bank, all of which are specifically reserved. The report reflects information available up to November 30, 2017. RIGHTS AND PERMISSIONS The material in this work is subject to copyright. Because The World Bank encourages dissemination of its knowledge, this work may be reproduced, in whole or in part, for noncommercial purposes as long as full attribution to this work is given. Any queries on rights and licenses, including subsidiary rights, should be addressed to World Bank Publications, The World Bank Group, 1818 H Street NW, Washington, DC 20433, USA; e-mail: [email protected]. -

Study on Airport Ownership and Management and the Ground Handling Market in Selected Non-European Union (EU) Countries

Study on airport DG MOVE, European ownership and Commission management and the ground handling market in selected non-EU countries Final Report Our ref: 22907301 June 2016 Client ref: MOVE/E1/SER/2015- 247-3 Study on airport DG MOVE, European ownership and Commission management and the ground handling market in selected non-EU countries Final Report Our ref: 22907301 June 2016 Client ref: MOVE/E1/SER/2015- 247-3 Prepared by: Prepared for: Steer Davies Gleave DG MOVE, European Commission 28-32 Upper Ground DM 28 - 0/110 London SE1 9PD Avenue de Bourget, 1 B-1049 Brussels (Evere) Belgium +44 20 7910 5000 www.steerdaviesgleave.com Steer Davies Gleave has prepared this material for DG MOVE, European Commission. This material may only be used within the context and scope for which Steer Davies Gleave has prepared it and may not be relied upon in part or whole by any third party or be used for any other purpose. Any person choosing to use any part of this material without the express and written permission of Steer Davies Gleave shall be deemed to confirm their agreement to indemnify Steer Davies Gleave for all loss or damage resulting therefrom. Steer Davies Gleave has prepared this material using professional practices and procedures using information available to it at the time and as such any new information could alter the validity of the results and conclusions made. The information and views set out in this report are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the official opinion of the European Commission. -

Road to Ichinobo, Matsushima from Tokyo and Sendai

Road to Matsushima CASE (A): Sendai airport (SDJ) Sendai sta. Matsushima SDJ Immigration at Narita International airport Domestic flight Arrive at Sendai airport (SDJ) Train #1 to Sendai station (Sendai Airport Line) Change train at Sendai station Train #2 to Matsushima station (JR Tohoku line) Arrive at Matsushima station Bus or TAXI or Walk NRT Tokyo Ichinobo (venue) HND CASE (B1): Narita airport (NRT) Sendai sta. Matsushima SDJ Immigration at Narita International airport Train #1 to Tokyo station (JR Narita Express) Change train at Tokyo station Train #2 to Sendai station (JR Tohoku Shinkansen) Change train at Sendai station Train #3 to Matsushima station (JR Tohoku line) Arrive at Matsushima station Bus or TAXI or Walk NRT Tokyo Ichinobo (venue) HND CASE (B2): Narita airport (NRT) Sendai sta. Matsushima SDJ Immigration at Narita International airport Train #1 to Ueno station (Keisei SKY liner) Change train at Ueno station (10 min. walk) Train #2 to Sendai station (JR Tohoku Shinkansen) Change train at Sendai station Train #3 to Matsushima station (JR Tohoku line) Arrive at Matsushima station Bus or TAXI or Walk NRT Tokyo Ichinobo (venue) HND CASE (C): Haneda airport (HND) Sendai sta. Matsushima SDJ Immigration at Haneda International airport Train #1 to Hamamatsucho station (Tokyo monorail) Change train at Hamamatsucho station Train #2 to Tokyo station (JR Yamanote line) Change train at Tokyo station Train #3 to Sendai station (JR Tohoku Shinkansen) Change train at Sendai station Train #4 to Matsushima station (JR Tohoku line) NRT Tokyo Arrive at Matsushima station HND Bus or TAXI or Walk Ichinobo (venue) Sendai station Time table Sendai station (Saturday and Holiday) Tohoku Line for Matsushima mark does not stop at Matsushima station. -

Recent Developments in Public- Private Partnerships in Japan

COUNTRY / PRACTICE Recent developments in public- private partnerships in Japan Masanori Sato and Shigeki Okatani of Mori Hamada & Matsumoto in Tokyo report on the latest changes to Japan’s PPP (public-private partnership) environment n 2015, there were significant developments in public-private partnerships (PPP) in Japan. The concession agreement for “The need for more I Sendai Airport was signed on December 1, 2015, and the con - cession agreement for Kansai International Airport (Kanku) and Osaka International Airport (Itami) was signed on December 15 efficient management of 2015. These projects are the first cases of airport privatisations in Japan where there were substantial uses of PPP frameworks, and the infrastructure, management of the airports was assigned to entities established ex - clusively with private capital. challenging fiscal Another recent development was the introduction of special legis - lation, passed into law by parliament in July 2015, enabling a local government to implement a toll road concession, the bidding process conditions, and the for which commenced in November 2015. The government is actively promoting PPP in light of socio- expectation PPPs will economic changes and fiscal conditions. It has set numerical targets, and has implemented a variety of measures to promote PPP proj - create new business ects. However, hurdles to implementing PPPs, especially in regard to concessions in certain sectors, including water and sewage, still opportunities are driving remain. This article discusses the government’s recent efforts to promote the government to PPPs and the latest developments in certain types of infrastructure development. intensively promote PFI A new era for PPPs in Japan In the Abe administration’s basic growth strategy, the Japan Revitali - Act concessions” sation Strategy, which was revised in 2015, central government calls upon local governments to offer more opportunities to the private sector to operate public facilities. -

Contact List of Animal Quarantine Service at Airport and Seaport

Contact list of Animal Quarantine Service at airport and seaport TEL Airport Seaport Name E-mail address New Chitose Airport , Wakkanai, Tomakomai, +81-123-24-6080 Hokkaido and Tohoku Branch Obihiro, Asahikawa, Muroran, Kushiro, Otaru, [email protected] Kushiro Ishikari-wan +81-138-84-5415 Hakodate, Aomori Hakodate, Hachinohe Hakodate Airport Sub-branch [email protected] Akita, Sendai, Yamagata, Ishinomaki, Akita, Onahama, +81-22-383-2302 Sendai Airport Sub-branch Fukushima, Hanamaki Sendai-Shiogama, [email protected] Akitafunakawa, Kamaishi Narita Branch, Cargo +81-476-32-6655 Narita International Airport, Kashima, Hitachinaka Inspection Division [email protected] Ibaraki (Hyakuri) Haneda Airport Branch +81-3-5757-9755 Tokyo International Airport (Cargo) [email protected] (Haneda) +81-3-3529-3021 Keihin Seaport (Tokyo) Tokyo Sub-branch [email protected] +81-47-432-7241 Chiba Chiba Annex [email protected] Yokohama Head Office Keihin Seaport +81-45- 201-9478 Animal-Products Inspection (Yokohama, Kawasaki) [email protected] Division +81-44-287-7412 Keihin Seaport (Kawasaki) Kawasaki Sub-branch [email protected] +81-25-275-4565 Shonai, Niigata Sakata, Niigata, Naoetsu Niigata Airport Sub-branch [email protected] Shizuoka Sub-branch Shizuoka Shimizu (Shimizu Seaport office) +81-54-353-5086 (Shizuoka Airport office) +81-548-29-2440 [email protected] +81-569-38-8577 Chubu International Airport Mikawa Chubu Airport Branch [email protected] +81-52-651-0334 Nagoya Nagoya Nagoya Sub-branch [email protected] +81-593-52-6918 -

SMTRI Japanese Infrastructure Market Updates Current Status and Issues

Japanese Infrastructure Market Updates Current Status and Issues of Concession PFI Ver.01 May 19, 2015 Sumitomo Mitsui Trust Research Institute Contents I Background ........................................................................................... 1 1 Infrastructure dealt with in this report ............................................... 1 2 The narrowing gap between supply and demand ............................ 2 2-1 Needs of public sector (supply side) ........................................ 2 2-2 Needs of investors (demand side) ............................................ 3 3 Social significance of public infrastructure market and introduction of concessions ............................................................. 3 3-1 Social significance of public infrastructure market .................... 3 3-2 History of public-private partnerships in Japan and introduction of concessions ............................................................................. 4 II Current Status of Concession PFI in Japan .......................................... 6 1 Size of market for concession PFI ................................................... 6 2 Current status of concession PFI in general .................................... 7 3 Airports ............................................................................................ 8 3-1 Sendai Airport .......................................................................... 8 3-2 Kansai International Airport and Osaka International Airport (Kansai International /Itami) ............................................................... -

Restarting International Flights After Seven Months Suspension - Reconnecting Japan and Taiwan As the Bridge to Asia

Press Release Oct. 25, 2020 Peach Aviation Limited Restarting International Flights after Seven Months Suspension - Reconnecting Japan and Taiwan as the Bridge to Asia - ・ Restarting with Osaka (Kansai) - Taipei (Taoyuan) route ・ Also resuming the Tokyo (Haneda/Narita) - Taipei (Taoyuan) route on Oct. 26 ・ Resumption of international flight operations after seven-months suspension of all international routes since March 2020 ・ Providing airport pickups services for customers arriving in Taipei Osaka, Oct. 25, 2020 - Peach Aviation Limited (“Peach,” Representative Director and CEO: Takeaki Mori) restarted Osaka (Kansai) - Taipei (Taoyuan) route on Oct. 25. In addition, the Tokyo (Haneda) -Taipei (Taoyuan) route and the Tokyo (Narita) -Taipei (Taoyuan) route will resume in that order on Oct. 26. Peach restarts operation of international flights after seven months suspension of all international flights since March 20. *Flight from Osaka (Kansai) to Taipei (Taoyuan) departing Kansai Airport for Taipei With the resumption of international flights, Peach will start providing airport pick up services* to customers arriving at Taipei Taoyuan Airport on Peach flights. Due to restrictions on using public transportation after arriving at the airport, Peach cooperates with a transport company providing service to Taipei city in order to support our passengers. In addition, we will start transportation services* sequentially at Kansai Airport, Haneda Airport and Narita Airport for passengers arriving in Japan. Pickup services can be reserved from Peach's website. We have also prepared the following page summarizing restrictions and precautions to take traveling to and from Taiwan. Note: Passengers Traveling to/from Taiwan https://www.flypeach.com/en/mp/others/information_crossborder?_ga Peach moves its boarding terminal at Narita Airport from Terminal 3 to Terminal 1 on Oct.25. -

Peach Launches New Base and Flights from Sendai Airport

Press Release Peach Launches New Base and Flights from Sendai Airport New Flights between Sendai – Sapporo (Shin-Chitose) and Sendai –Taipei (Taoyuan) Peach Brings Tohoku and Asia Closer Together! ・ New routes launched: Sendai – Sapporo (Shin-Chitose) from September. 24 and Sendai – Taipei (Taoyuan) from September. 25 ・ New flights from Shin-Chitose to Fukuoka and Taipei (Taoyuan) also launched ・ Special website, COMOMO, set up with Miyagi Prefecture, commemorating Sendai as a new travel hub Osaka 25 September, 2017 - Peach Aviation Limited (“Peach”; Representative Director and CEO: Shinichi Inoue) has set up a base in Sendai Airport and launched new routes including flights to Sapporo (Shin-Chitose), launched on September 24, as well as flights to Taipei (Taoyuan), which launched the next day on September 25. Sapporo (Shin-Chitose) flights depart twice daily, while Taipei (Taoyuan) flights depart four days per week (Mon/Tues/Thurs/Sat). New flights from Shin-Chitose Airport to Fukuoka and Taipei (Taoyuan) went into service on September 24. Including Peach's existing Sendai – Osaka (Kansai) route, this brings the total number of Peach routes serving Sendai Airport to three. Likewise, including Peach's existing Shin-Chitose (Sapporo) – Osaka (Kansai) route, it brings the total routes serving Shin-Chitose Airport to three as well, representing an effective expansion of Peach's network from Tohoku and Hokkaido. Landing ceremony for the new Taipei – Sendai route/September 25 at Sendai Airport> Peach's CEO, Shinichi Inoue, commented, "With Sendai Airport as an air-travel gateway to Tohoku, Peach hopes to contribute even more to Tohoku reconstruction by bringing more customers than ever to the area. -

Transportation Guide & Maps

TRANSPORTATION GUIDE & MAPS (Keep an electronic copy of this on your internet-enabled devices to access the links. Electronic copy of this guide is downloadable at neaef.org/young-leaders-program) From Tokyo Narita Airport to Sendai Station IMPORTANT: Take a picture of your train ticket showing the fare for reimbursement purposes. In most cases, your ticket will be collected in the train. From Narita Airport, take the Skyliner going to Keisei Ueno Station. You can purchase the ticket online in advance using this link: http://www.keisei.co.jp/keisei/tetudou/skyliner/e-ticket/en/ticket/skyliner-ticket/index.php Fare: 2,470 yen Time: Approximately 47 minutes from Narita Airport Terminal 1 Approximately 43 minutes from Narita Airport Terminal 2 From the Ueno Station, take the Komachi or Hayabusa (Tohoku Shinkansen) going to Sendai Station. It would be best to buy the ticket at Ueno Station because online reservation requires exact time of boarding. Fare: 10,790 yen (one way) Time: 86-88 minutes (Komachi) & 86-89 minutes (Hayabusa) • NARITA AIRPORT FLOOR MAP: https://www.narita- airport.jp/en/map/?map=4&terminal=1 • JR-EAST TRAIN TIMETABLE (TOKYO TO SENDAI): https://www.eki- net.com/pc/jreast-shinkansen- reservation/English/wb/common/timetable/e_tohoku_d/index.html • JR-EAST TRAIN TIMETABLE (SENDAI TO TOKYO): https://www.eki- net.com/pc/jreast-shinkansen- reservation/English/wb/common/timetable/e_tohoku_d/index.html For time-specific detailed steps using your GPS on your phone, please download/use Google Maps: https://www.google.com/maps From Tokyo Haneda Airport to Sendai Station IMPORTANT: Take a picture of your train ticket showing the fare for reimbursement purposes. -

Japan 2011 Earthquake: U.S

Japan 2011 Earthquake: U.S. Department of Defense (DOD) Response Andrew Feickert Specialist in Military Ground Forces Emma Chanlett-Avery Specialist in Asian Affairs March 17, 2011 Congressional Research Service 7-5700 www.crs.gov R41690 CRS Report for Congress Prepared for Members and Committees of Congress Japan 2011 Earthquake: U.S. Department of Defense (DOD) Response Overview With almost 40,000 U.S. troops stationed in Japan, the March 11, 2011, earthquake and tsunami is unique in that U.S. forces and associated resources were located in close proximity to deal with the crisis. All services—Army, Navy, Marine Corps, and Air Force—are present in Japan in various capacities. In addition, U.S. forces train regularly with their Japanese Self Defense Force (SDF) counterparts, including many humanitarian assistance and disaster relief exercises. With 100,000 SDF troops called up to respond to the disaster, U.S. forces were able to coordinate their efforts almost immediately to provide support for the Japanese responders. Within five days of the earthquake, the SDF had deployed 76,000 personnel (45,000 ground, 31,000 air and maritime); 194 rotary aircrafts and 322 fixed-wings; and 58 ships. As of March 16, the SDF had rescued 19,300 people, in addition to supporting activities at the troubled nuclear reactors.1 Operational Update2 DOD officials report that as of the morning of March 17, 14 U.S. naval ships and their aircraft and 17,000 sailors and Marines are now involved in humanitarian assistance and disaster relief efforts in and around Japan. These efforts have included 132 helicopter sorties and 641 fixed- wing sorties moving both people and supplies, assisting in search and rescue efforts, and delivering 129,000 gallons of water and 4,200 pounds of food. -

Service to Chubu Centrair International Airport Announced -New Flights from Nagoya (Chubu) to Sapporo (New Chitose) and Sendai

Press Release October 21, 2020 Peach Aviation Limited Service to Chubu Centrair International Airport Announced -New Flights from Nagoya (Chubu) to Sapporo (New Chitose) and Sendai- ・ Twice-daily round-trip service to Sapporo and once-daily round-trip service to Sendai to begin December 24 ・ Flights will fly into Terminal 1 of Chubu Centrair International Airport Osaka October 21, 2020 - Peach Aviation Limited (“Peach”; Representative Director and CEO: Takeaki Mori) announced new routes to Chubu Centrair International Airport today. The two new routes are between Nagoya (Chubu) and Sapporo (New Chitose) and between Nagoya (Chubu) and Sendai. Both will begin on December 24. The Nagoya (Chubu) to Sapporo (New Chitose) route will make two round trips per day, and the Nagoya (Chubu) to Sendai route will make one daily round trip. Both will fly into Terminal 1 at Chubu Centrair International Airport. Airfares start at ¥4,690 for the Sapporo (New Chitose) route and ¥4,990 for the Sendai route. Tickets for both routes will go on sale today at 4:00 p.m. When announcing the new routes to Chubu Centrair International Airport, Peach CEO Mori stated, “Peach’s mission is to continue to stably provide affordable air travel with low fares and to connect regions, with a priority on COVID-19 infection countermeasures. Despite the harsh environment surrounding the airline industry, we will contribute to the revitalization of Japan’s economy by fulfilling this mission.” On October 25, Peach will move its Narita Airport operations from Terminal 3 to Terminal 1, which is directly connected to the train station. -

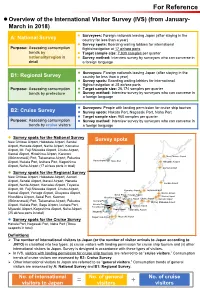

For Reference Overview of the International Visitor Survey (IVS) (From January- March in 2018)

For Reference Overview of the International Visitor Survey (IVS) (from January- March in 2018) Surveyees: Foreign nationals leaving Japan (after staying in the A: National Survey country for less than a year) Survey spots: Boarding waiting lobbies for international Purpose: Assessing consumption flights/navigation at 17 air/sea ports trends by Target sample size: 7,830 samples per quarter nationality/region in Survey method: Interview survey by surveyors who can converse in detail a foreign language Surveyees: Foreign nationals leaving Japan (after staying in the B1: Regional Survey country for less than a year) Survey spots: Boarding waiting lobbies for international flights/navigation at 25 air/sea ports Purpose: Assessing consumption Target sample size: 26,174 samples per quarter trends by prefecture Survey method: Interview survey by surveyors who can converse in a foreign language Surveyees: People with landing permission for cruise ship tourism B2: Cruise Survey Survey spots: Hakata Port, Nagasaki Port, Naha Port Target sample size: 960 samples per quarter Purpose: Assessing consumption Survey method: Interview survey by surveyors who can converse in trends by cruise visitors a foreign language Survey spots for the National Survey Survey spots New Chitose Airport, Hakodate Airport, Sendai Airport, Haneda Airport, Narita Airport, Komatsu Airport, Mt. Fuji Shizuoka Airport, Chubu Airport, Kansai Airport, Hiroshima Airport, Kanmon (Shimonoseki) Port, Takamatsu Airport, Fukuoka New Chitose Airport Naha Airport Airport, Hakata Port, Izuhara Port, Kagoshima Naha Port Hakodate Airport Airport, Naha Airport (17 air/sea ports in total) Aomori Airport Survey spots for the Regional Survey New Chitose Airport, Hakodate Airport, Aomori Airport, Sendai Airport, Ibaraki Airport, Haneda Sendai Airport Airport, Narita Airport, Komatsu Airport, Toyama Airport, Mt.