Challenges and Opportunities for Canada- Korea Cooperation

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Survival Guide for International Students 2020

Survival Guide 2020 Survival Guide for International Students 2020 KAIST College of Business, 85 Hoegi-ro, Dongdaemun-gu, Seoul, Korea 02455 www.business.kaist.edu 1 Survival Guide 2020 Table of Contents Life as KCB Student Introduction ---------------------------------------------------------- 4 Arrival Information ------------------------------------------------- 5 Academic Information --------------------------------------------- 9 Holiday Information ------------------------------------------------ 12 Campus Map -------------------------------------------------------- 14 Campus Facilities -------------------------------------------------- 15 Sports Facilities ----------------------------------------------------- 20 Housing Information ----------------------------------------------- 21 Campus Area ------------------------------------------------------- 24 Visa & Alien Registration ----------------------------------------- 26 Health Information ------------------------------------------------- 27 Life in Korea About Korea --------------------------------------------------------- 29 Transportation ------------------------------------------------------ 30 Living in Korea ------------------------------------------------------ 34 Medical Services & Hospitals ----------------------------------- 35 Expenses ------------------------------------------------------------ 36 Attractions & Entertainment ------------------------------------- 38 KAIST College of Business, 85 Hoegi-ro, Dongdaemun-gu, Seoul, Korea 02455 www.business.kaist.edu 2 Survival -

CAMPUS Asia Program Overview FY2017 Budget: 650 Million Yen

CAMPUS Asia Program Overview FY2017 budget: 650 million yen CAMPUS Asia is a program that promotes quality-assured student exchanges through cooperation among the governments, quality assurance organizations, and universities of Japan, China, and Korea. From FY2011, ten pilot programs were selected through joint screening by the three countries and conducted. Since FY2016, in addition to eight programs that applied from among the ten pilot programs, nine new programs by the university consortium participating in CAMPUS Asia have been added for a total of 17 programs that have begun the full-fledged implementation of their activities. Record/plan of exchanges (no. of Japanese students sent abroad, foreign students received in Japan) - FY 2011-2015 (actual): Sent: 1,392, received: 1,485 - FY 2016-2020 (planned): Sent: 2,199; received: 2,076 Details At the 2nd Japan-China-Korea Summit in October 2009, Japan proposed, and agreement was reached on, trilateral high-quality inter- university exchanges. In April 2010, the trilateral 1st Experts Meeting was held in Tokyo (Japan side chairman: Yuichiro Anzai, President, Japan Society for the Promotion of Science). Agreement was reached on “CAMPUS Asia”* as the name for the program. *Stands for: “Collective Action for Mobility Program of University Students in Asia” In April 2015, at the 5th China-Japan-Korea Committee for Promoting Exchange and Cooperation among Universities, the three countries agreed that, with the end of the pilot program period, from FY2016, they would: 1) increase the number of trilateral inter- university collaboration programs, including the exchanges carried out as pilot programs, 2) make efforts to expand the collaborative framework of the Program (in the mid- and long-term) to the ASEAN countries. -

Curriculum Vitae Hye Young

CURRICULUM VITAE HYE YOUNG KIM Born in Gongju, Changnam, South Korea in 1982 Assistant Professor of Art, Winston-Salem State University, NC, USA Assistant Professor of Art Department of Art EDUCATION + Visual Studies 2013.05 Master of Fine Arts, Art and Technology 601 S. Martin Luther King Jr. Dr School of Art and Art History, University of Florida, Gainesville, FL, USA Carolina Hall G32 2009.05 Master of Fine Arts, Painting Winston-Salem, NC 27110 Sam Fox School of Design & Visual Arts, Washington University in St. Louis, MO, USA Office: 336-750-3343 2007.02 Bachelor of Fine Arts in Painting Emaiil: [email protected] Department of Fine Arts and Design, Korea University, Seoul, South Korea 2004-2005 Study Abroad Program, 1 Year Visiting Student University of California at Davis, CA, USA TEACHING EXPERIENCE 2013-present Assistant Professor of Art, Art and Visual Studies Winston-Salem State University, NC, USA 2011-2013 Instructor as record, Graduate Graduate Teaching Assistantship University of Florida, Gainesville, FL, USA 2011 Visting Artist “Tracing Human Existence,” McDonnell Academy Alumni Workshop, Washington University in St. Louis, MO, USA 2010 Visiting Artist, “Art in Higher Education in US”, Chungnam Arts High School Cheonan, Korea 2010 Workshop instructor, “Recycle Art”, Solstice Workshop Art Studio, Seattle, WA, USA 2009 Workshop instructor, “Nature Art” YMCA camp, Seatlle, WA, USA 2009 Workshop instructor, “Around the world”, COCA, Saint Louis, MO, USA 2008-2009 Teaching Assistant, Washington University in St. Louis, MO, USA 2006 Art Instructor, Seoul Guui Elementary School, Seoul, Korea 2005-2006 Visiting Art Instructor, Hong Teacher Art Education Co. -

Workshop Program

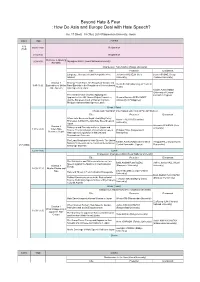

Beyond Hate & Fear : How Do Asia and Europe Deal with Hate Speech? Jan. 17 (Wed) - 18 (Thu), 2018 Ritsumeikan University, Japan DATE TIME EVENT 1/16 16:00-18:00 Registration (TUE) 8:30-9:00 Registration Welcome & Opening 9:00-9:30 Myungkoo KANG (Seoul National University) Remarks Chairperson: Yuko KAWAI (Rikkyo University) Title Presenter Discussant Language, Hatespeech and Xenopobia in the Johannes WILHELM (Keio Laura ASCONE (Cergy- Internet University) Pontoise University) Session 1 Proving “Real” Harm: An Analysis of Gender and Vivian SHAW (University of Texas at 9:45-11:00 Exploration of Online Race/Ethnicity in the Regulation of Internet-based Austin) Hate Speech Hate Speech in Japan Natalie ALKIVIADOU (University of Central Free Market Place of Ideas: Applying the Lancashire Cyprus) Approach of the UN Human Rights Committee Gemmo Bautista FERNANDEZ and the European Court of Human Rights in (University of Philippines) Philippine Internet Hate Speech Cases Break (15min) Chairperson: Younghan Cho (Hankuk University of Foreign Studies) Title Presenter Discussant When Hate Becomes Illegal: Analyzing Policy Naoto HIGUCHI (Tokushima Processes to Enact the Anti-Hate Speech Law in University) Japan Session 2 Johannes WILHELM (Keio Dialogues and Diversity in Korea, Japan and University) 11:15-12:30 When Hate France: The Contribution of International Law to Philippa HALL (Independent Becomes Illegal Hate Speech Legislation in National and Researcher) Transnational Contexts The Legal Regulation of Hate Speech: The United Natalie ALKIVIADOU -

ZEUS EXPERIMENT at HERA ' ZEUS Collaboration 2 Group from the Institute of Nuclear Physics Includes: P

PL9700208 28 Section V ,.,.-; ZEUS EXPERIMENT AT HERA ' ZEUS Collaboration 2 Group from the Institute of Nuclear Physics includes: P. Borzeniski, J. Chwastowski, A. Eskreys, K. Piotrzkowski, M. Przybycieri, M. Zachara, L. Zawiejski (physicists) and J. Andruszkow, B. Dajarowski, W. Daniluk, P. Jurkiewicz, A. Kotarba, K. Oliwa. W. Wierba (engineers and technicians) Third year of HERA operation was a very successful one for the HERA crew. Experiments (ZEUS and HI) collected more than 3pb~1 of the integrated luminosity compared to ()00nb~^ in the previous year. Higher luminosity means also higher rates and higher background. That created new problems for our experiment at the beginning of the running period. The common effort of all groups taking care of the different detector components resulted in a smooth and successful running of the ZEUS experiment. The main responsibility of the Cracow group is the reliable performance of the Luminosity Monitor, which has been designed and built by our group. That means the maintenance of the detector, continuous development of the online and offline software tools and the luminosity measurement itself. A very detailed offline analysis of the 1993 luminosity data was done in 1994. This resulted in much better understanding of the systematic effects influencing the luminosity measurement. The systematic error in the determination of the integrated luminosity is now below 2.5%. Modification of the hardware setup, especially replacement of the photomultipliers in the calorimeters, made during the 1993/1994 winter shutdown, allowed for more stable opera- tion in the 1994 running period. Much improvement has also been achieved in both offline and online software. -

HRNK, NYU School of Law, the Hurford Foundation, CFR's Winston

20th Annual Timothy A. Gelatt Dialogue on the Rule of Law in East Asia International Human Rights: North Korea, China and the UN Tuesday, November 11, 2014 1:30–7:00 p.m. Greenberg Lounge 40 Washington Square South NYU School of Law International Human Rights: North Korea, China and the UN 1:30 p.m. Welcome Jerome Cohen, Professor and Co-Director, US-Asia Law Institute, NYU School of Law; Adjunct Senior Fellow for Asia, Council on Foreign Relations Greg Scarlatoiu, Executive Director, The Committee for Human Rights in North Korea 1:40 p.m. The Current Context Keynote: An Overview: The DPRK and the World Stephen Bosworth, Senior Fellow, Harvard Kennedy School of Government; Chairman, US-Korea Institute, Johns Hopkins University; Former US Ambassador to South Korea, US Special Repre- sentative for North Korea Policy; Dean, Fletcher School of Law and Diplomacy at Tufts University Comment: Are We Prisoners of Korean History? Charles Armstrong, Korea Foundation Professor of Korean Studies in the Social Sciences, Columbia University Discussion Moderator: Dr. Myung-Soo Lee, Senior Research Scholar, US-Asia Law Institute, NYU School of Law 2:30 p.m. The Refugee Problem, International Law and China’s Role My Struggles as a Defector in North Korea, China and South Korea Hyeonseo Lee, Refugee Activist China’s Forced Repatriation of North Korean Refugees and International Law Roberta Cohen, Non-Resident Senior Fellow, Brookings Institution; Co-Chair, The Committee for Human Rights in North Korea Rescuing North Korean Refugees: The Story of Asia’s Underground Railroad Melanie Kirkpatrick, Senior Fellow, Hudson Institute; author of Escape from North Korea: The Untold Story of Asia’s Underground Railroad Discussion Moderator: Philip Alston, John Norton Pomeroy Professor of Law; Faculty Director and Co-Chair, Center for Human Rights and Global Justice, NYU School of Law 3:45 p.m. -

About Korea University 2017

1 About Korea University About Korea 2 3 2017 About Korea University Greeting 04 KU History 05 KU history has maintained the pride of the Korean people Inside KU’s Icon 06 An icon, the first step towards Global KU KU Change 08 World’s Top 50 University 12 Ready To Enter the World’s Top 50 by 2020 Campus Facilities 14 Exceptional campus facilities Global KU 18 A cradle of global leaders Campus Life 22 Six Must-Dos for KU students Colleges & Graduate Schools 26 Colleges, the heart of KU KU Facts 52 Statistics KU Campus 72 Campus information Greeting KU History About Korea University About Korea 04 055 1905 Realizing the goal Founded as Bosung College, the first institute of higher education in Korea of the world’s top 100 together, Yong-ik Lee, also known as Chungsukgong, Treasurer of the Royal Household of the Korean Empire, established Bosung College, the We now aspire to predecessor of Korea University, with the belief “Education Saves KU’s new mission. the Nation”. 1934 Moved to the Anam Campus The Main Building, a representation of the aspirations of the Ko- rean people, constructed in Anam-dong. Greetings from Korea University! As President of KU with a strong sense of responsibility and 1946 Korea University, an overarching name sincerity, I am putting forth my best efforts to make the future of KU stand tall in the world, Permission granted on August 15 to establish a university. building upon the proud history of KU as the nation’s pride and hope. Name changed to Korea University. -

College of Humanities Kyung Hee University

spring 2018 No. 10 CollegeCollege ofof HumanitiesHumanities KyungKyung HeeHee UniversityUniversity st 1 Semester, 2018 l Published by Jong-Bok Kim ll College of Humanities ll 02)961-0221~2 ll [email protected] SpringSpring 2018,2018, CollegeCollege ofof HumanitiesHumanities EventsEvents Ø Reorganization of the School of English The School of English has been reorganized into two departments: English Language and Literature (ELL) and Applied English Language and Translation Studies (AELTS). Through this reorganization, students will be offered greater balance and competitiveness in their various majors and prospective careers. Intellectual and pedagogical exchanges between ELL and AELTS will make a significant contribution to the overall quality of English language education at Kyung Hee University. ◉ Organizational Restructuring Before the restructuring After the restructuring English Language and Literature School of English Applied English Language & Translation Studies Ø 2018 Humanities Forum The Humanities Forum encourages in-depth scholarly research and the sharing of new academic projects with faculty, graduate students, and undergraduate students. In the first semester of 2018, three faculty members, including new professor Sung-Beom Ahn from the Department of Korean Language and Literature, will discuss their research projects with the humanities community. The 2018 Humanities Forum will continue throughout the academic year with an engaging line-up of monthly presenters. ◉ Forum Schedule 2018.04.12 (Thurs) 18th Prof. Sung-Beom Ahn (Dept. of Korean) 2018.04.12 (Thurs) 19th Prof. Ji-Ho Chung (Dept. of History) 2018.06.14 (Thurs) 20th Prof. Woo-Sung Heo(Dept. of Philosophy) Ø Winter Overseas Training Program An Overseas Training Program was conducted during the 2017 winter vacation period in order to explore the relationship between global knowledge and the particularities of various majors. -

Fudan-Sciences Po “Europe and Asia in Global Affairs” Double Degree (DD) Program

Fudan-Sciences Po “Europe and Asia in Global Affairs” Double Degree (DD) Program 1. Fudan University and SIRPA at a Glance Founded in 1905, Fudan University has been being one of the top universities in China and well-known in the world. Its name "Fudan", literally meaning "(heavenly light shines) day after day", indicates inexhaustible self-reliance and industriousness. It is located in a cosmopolitan global city, Shanghai, also an important economic center of China and the world. School of International Relations and Public Affairs (SIRPA) is a leading school in international relations, political science and public administration in China. It aims to train the best talents for state and public affairs, and potential academics. The subject of international relations in SIRPA is ranked in the most first level in China. It attracts hundreds foreign students of different level from undergraduate, master to Ph.D., and various exchange program participants. 2. Introduction of the DD Program The Double Degree Program on Europe and Asia in Global Affairs was established by Fudan University and Sciences Po in 2010. It provides students who are interested in analyzing European and Asian affairs from both comparative and international relations perspectives with the excellent research network between Fudan University and Sciences Po. This program is aimed, at the same time, at European specialists who would like to deepen their understanding of Europe through the comparison to Asia; at Asian specialists who aspire to strengthen their understanding of Asia in relation to other regions, and at international relations specialists who are eager to acquire a more specific insight on the challenges and content of Europe-Asia relations. -

University Acceptances

BUSAN FOREIGN SCHOOL Embracing Diversity, Striving for Excellence BUSAN FOREIGN SCHOOL UNIVERSITY ACCEPTANCES Below is a list of University acceptances covering the period from the academic year 2007-08 to the 2019-20 one: • Abilene Christian University • Carnegie Mellon University • American University in Dubai, United Arab • Case Western Reserve University Emirates • Chapman University • American University of Sharjah, United Arab • City University of Hong Kong, Hong Kong Emirates • City University of London, United Kingdom • American University, Washington D.C. • Clark University • Amherst College • Clarkson University • Arizona State University • Clemson University • Asia Pacific University, Japan • CMH Paris, France • Auburn University • Colgate University • Azusa Pacific University • College of William and Mary • Babson College • Colorado State University • Baylor University • Columbia College, Chicago • Berklee School of Music • Columbia University • Birkbeck, University of London, United Kingdon • Concordia University, Canada • Boston College • Concordia University, Wisconsin • Boston University • Cornell College • Bowie State University • Cornell University • Brandeis University • Dalhousie University, Canada • Brigham Young University • Dalian University of Foreign Languages, China • Brown University • Denison University • Brunel University London, United Kingdon • DePaul University • Bucknell University • Dongseo University, Korea • California College of the Arts • Doshisha University, Japan • California Polytechnic State University -

Study Abroad at Korea University 2017 Study Abroad at Korea University

2017 STUDY ABROAD AT KOREA UNIVERSITY 2017 STUDY ABROAD AT KOREA UNIVERSITY A Message from the President Dear International Students, There has never been a better time than the present to be an international student, indeed with so many inspiring and challenging academic programs at universities all over the world to choose from, we know there are many options available to you. For this reason we are very pleased you are considering studying in Korea and at Korea University (KU). Currently, KU is recognized as the top university in the nation in the area of international education. We have made a conscious effort to provide our students with a top-quality education that exposes them to different ideas and cultures from around the world. This plan also includes an important component of sharing the best of Korean culture with international students who come and study with us here in Seoul. Over the past eight years we have seen a dramatic increase in both the number of courses offered in English (currently about 40%) and in the number of international students who have selected Korea University as their desti- nation of choice for a study abroad experience. Last semester alone (Fall 2016) we welcomed almost 9,500 students to our campus from all parts of the globe. This is certainly a strong testament to the quality of the academic experience offered at KU and to the warm hospitality and inviting environment we have created on campus. We realize that studying in a foreign country presents its own challenges and difficulties. I myself was once an international student in the US in the 1980s so I know firsthand how demanding -- but ultimately rewarding -- the experience can be. -

Curriculum Vitae

Jacques R. Giard Curriculum Vitae EDUCATION Leadership Academy Certificate (2002) Arizona State University Ph.D. (1987) Cultural Studies Concordia University Montréal, Québec H. Dip. Design (1971) Industrial Design (Engineering) Birmingham Polytechnic Birmingham, UK Courses in Industrial administration (1971) University of Aston Birmingham, UK. Dip. Design (1969) Furniture Design Institut des arts appliqués Montréal, Québec EMPLOYMENT EXPERIENCE Academic Arizona State University Herberger Institute for Design and the Arts The Design School Professor of Industrial Design (July 2010 to present) Interim Assistant Director Academic Personnel (August 2017 to present) Coordinator Bachelor of Science in Environmental Design (October 2014 to present) Director MSD/PhD Programs (June 2009 to June 2010) College of Design Director Cross-College Programs (BA/MSD/PhD) (August 2006 to May 2009) Director Design Studies (BA/MSD) (July 2005 to July 2006) Director School of Design (July 1998 to June 2005) Carleton University Faculty of Engineering and Design Director, Centre for Industrial Design Research (July 1997 to June 1998) Appointed Full Professor (July 1988) January 2018 1 Jacques R. Giard Curriculum Vitae Director, School of Industrial Design (July 1985 to June 1994) Acting Director (July 1984 to June 1985) Associate Professor (July 1979 to June 1988) University of Alberta Department of Art and Design Assistant Professor and Coordinator Industrial Design Division (July 1976 to June 1979) Visiting Professor (September 1975 to June 1976) Professional Practice Private Practice Since 1979 President and Partner Egler Giard Design Associates Limited Edmonton, Alberta May 1976 to May 1979 Staff Designer Performance Sailcraft Inc. Pointe Claire, Québec January 1974 to May 1975 Design Director Centre de recherche industrielle du Québec (CRIQ) Ste Foy, Québec May 1972 to December 1973 Designer Girard, Bruce and Associates.