British Columbia Financial & Economic

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

MANAGEMENT PLAN November 2003

MANAGEMENT PLAN November 2003 for Stikine Country Protected Areas Mount Edziza Provincial Park Mount Edziza Protected Area (Proposed) Stikine River Provincial Park Spatsizi Plateau Wilderness Provincial Park Gladys Lake Ecological Reserve Ministry of Water, Land Pitman River Protected Area and Air Protection Environmental Stewardship Chukachida Protected Area Division Skeena Region Tatlatui Provincial Park Stikine Country Protected Areas M ANAGEMENT LAN P November 2003 Prepared by Skeena Region Environmental Stewardship Division Smithers BC Stikine Country Protected Areas Management Plan National Library of Canada Cataloguing in Publication Data British Columbia. Environmental Stewardship Division. Skeena Region. Stikine Country Protected Areas management plan Cover title: Management plan for Stikine Country Protected Areas. Issued by: Ministry of Water, Land and Air Protection, Environmental Stewardship Division, Skeena Region. “November 2003” “Mount Edziza Provincial Park, Mount Edziza Protected Area (Proposed), Stikine River Provincial Park, Spatsizi Plateau Wilderness Provincial Park, Gladys Lake Ecological Reserve, Pitman River Protected Area, Chukachida Protected Area, Tatlatui Provincial Park”—Cover. Also available on the Internet. Includes bibliographical references: p. ISBN 0-7726-5124-8 1. Protected areas - British Columbia – Stikine Region. 2. Provincial parks and reserves - British Columbia – Stikine Region. 3. Ecosystem management - British Columbia – Stikine Region. I. British Columbia. Ministry of Water, Land and Air Protection. -

Fish 2002 Tec Doc Draft3

BRITISH COLUMBIA MINISTRY OF WATER, LAND AND AIR PROTECTION - 2002 Environmental Indicator: Fish in British Columbia Primary Indicator: Conservation status of Steelhead Trout stocks rated as healthy, of conservation concern, and of extreme conservation concern. Selection of the Indicator: The conservation status of Steelhead Trout stocks is a state or condition indicator. It provides a direct measure of the condition of British Columbia’s Steelhead stocks. Steelhead Trout (Oncorhynchus mykiss) are highly valued by recreational anglers and play a locally important role in First Nations ceremonial, social and food fisheries. Because Steelhead Trout use both freshwater and marine ecosystems at different periods in their life cycle, it is difficult to separate effects of freshwater and marine habitat quality and freshwater and marine harvest mortality. Recent delcines, however, in southern stocks have been attributed to environmental change, rather than over-fishing because many of these stocks are not significantly harvested by sport or commercial fisheries. With respect to conseration risk, if a stock is over fished, it is designated as being of ‘conservation concern’. The term ‘extreme conservation concern’ is applied to stock if there is a probablity that the stock could be extirpated. Data and Sources: Table 1. Conservation Ratings of Steelhead Stock in British Columbia, 2000 Steelhead Stock Extreme Conservation Conservation Healthy Total (Conservation Unit Name) Concern Concern Bella Coola–Rivers Inlet 1 32 33 Boundary Bay 4 4 Burrard -

GEOLOGY of the EARLY JURASSIC TOODOGGONE FORMATION and GOLD-SILVER DEPOSITS in the TOODOGGONE RIVER MAP AREA, NORTHERN BRITISH COLUMBIA by Larry J

Province of British Columbia MINERAL RESOURCES DIVISION Ministry oi Energy, Mines and Geological Survey Branch Petroleum Resources Hon. Anne Edwards, Minister GEOLOGY OF THE EARLY JURASSIC TOODOGGONE FORMATION AND GOLD-SILVER DEPOSITS IN THE TOODOGGONE RIVER MAP AREA, NORTHERN BRITISH COLUMBIA By Larry J. Diakow, Andrejs Panteleyev, and Tom G. Schroeter BULLETIN 86 MINERAL RESOURCES DIVISION Geological Survey Branch Canadian Cataloguing in Publication Data Diakow, Larry, I. Geology of the early Jurassic Toodoggone Formation and gold-silvei depositsin the Toodoggone River map area, northern British Columbia VICTORIA BRITISH COLUMBIA (Bulletin, ISSN 0226-7497; 86) CANADA Issued by Geological Survey Branch. Includes bibliographical references: p January 1993 ISBNO-7718-9277-2 1. Geology - Stratigraphic - Jurassic. 2. Gold ores Geological researchfor this -Geology - British Columbia - Toodoggone River Region. 3. Silver ores - British Columbia - Toodoggone River publication was completed during Region. 4. Geology - British Columbia - Toodoggone the period 1981 to 1984. River Region. 5. Toodoggone Formation (B.C.) I. Fanteleyev, Andrejs, 1942- 11. Schroeter, T. G. In. British Columbia. Geological Survey Branch. IV. British Columbia. V. Title. VI. Series: Bulletin (British Columbia. Minisrry of Energy, Mines and Petroleum Resources); 86. TN414C32B731992 551.7'66'0971185 C92-092349.6 Lawyers gold-silver deposit looking northwesterly with Amethyst Gold Breccia (AGB) and Cliff Creek (CC) zones indicated. Cheni Gold Mines camp is in the lower centre and the mill site at the left of the photograph. Flat-lying ash-flow tuffs of the Saunders Member (Unit 6) form the dissected plateauand scarps in the foreground. Silica-clay-alunite capping Alberts Hump, similar to nearby precious metal bearing advanced argillic altered rocks of the A1 deposit (AI), are barely visible to the north of Toodoggone River and 5 kilometres beyond Metsantan Mountain. -

Age Determination and Geological Studies

PAPER 81-2 AGE DETERMINATIONS AND GEOLOGICAL STUDIES K-Ar Isotopic Ages, Report 15 R.D. STEVENS, R.N. DELABIO, G.R. LACHANCE 1982 ©Minister of Supply and Services Canada 1982 Available in Canada through authorized bookstore agents and other bookstores or by mail from Canadian Government Publishing Centre Supply and Services Canada Hull, Quebec, Canada K1A 0S9 and from Geological Survey of Canada 601 Booth Street Ottawa, Canada K1A 0E8 A deposit copy of this publication is also available for reference in public libraries across Canada Cat. No. M44-81/2E Canada: $4.00 ISBN 0-660-11114-4 Other countries: $4.80 Price subject to change without notice CONTENTS 1 Abstract/Resume 1 Introduction I Geological time scaies 1 Experimental procedures 1 Constants employed in age calculations 2 References 2 Errata 3 Isotopic Ages, Report 15 3 British Columbia (and Washington^ 17 Yukon Territory 2H District of Franklin 29 District of Mackenzie 30 District of Keewatin 33 Saskatchewan 36 Manitoba 37 Ontario Quebec New Brunswick 46 Nova Scotia 47 Newfoundland and Labrador Offshore 50 Ghana 51 Appendix Cumulative index of K-Ar age determinations published in this format Figures 2 1. Phanerozoic time-scale 2 2. Precambrian time-scale 22 3. Geology of the "Ting Creek" intrusion 23 4. Cross sections of the "Ting Creek" intrusion 28 5. Potassium-argon whole rock ages of mafic igneous rocks in the Fury and Hecla and Autridge formations AGE DETERMINATIONS AND GEOLOGICAL STUDIES K-Ar Isotopic Ages, Report 15 Abstract Two hundred and eight potassium-argon age determinations carried out on Canadian rocks and minerals are reported. -

Botanical and Physiographic Reconnaissance of Northern British Columbia

Brigham Young University Science Bulletin, Biological Series Volume 14 Number 4 Article 1 9-1971 Botanical and physiographic reconnaissance of northern British Columbia Stanley L. Welsh Department of Botany, Brigham Young University, Provo, Utah 84601 J. Keith Rigby Department of Geology, Brigham Young University, Provo, Utah 84601 Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/byuscib Part of the Anatomy Commons, Botany Commons, Physiology Commons, and the Zoology Commons Recommended Citation Welsh, Stanley L. and Rigby, J. Keith (1971) "Botanical and physiographic reconnaissance of northern British Columbia," Brigham Young University Science Bulletin, Biological Series: Vol. 14 : No. 4 , Article 1. Available at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/byuscib/vol14/iss4/1 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Western North American Naturalist Publications at BYU ScholarsArchive. It has been accepted for inclusion in Brigham Young University Science Bulletin, Biological Series by an authorized editor of BYU ScholarsArchive. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. r?. J Brigham Young University haivm u .UJMlVERSiTvirj Science Bulletin BOTANICAL AND PHYSIOGRAPHIC RECONNAISSANCE OF NORTHERN BRITISH COLUMBIA by Stanley L. Welsh and J. Keith Rigby BIOLOGICAL SERIES — VOLUME XIV, NUMBER 4 SEPTEMBER 1971 BRIGHAM YOUNG UNIVERSITY SCIENCE BULLETIN BIOLOGICAL SERIES Editor: Stanley L. Welsh, Department of Botany, Brigham Young University, Provo, Utah Members of the Editorial Board: Vernon J. Tipton, Zoology Ferron L. Anderson, Zoology Joseph R. Murdock. Botany Wilmer W. Tanner, Zoology Ex officio Members: A. Lester Allen, Dean, College of Biological and Agricultural Sciences Ernest L. Olson, Chairman, University Publications The Brigham Young University Science Bulletin, Biological Series, publishes acceptable papers, particularly large manuscripts, on all phases of biology. -

Late-Glacial Alpine Glacier Advance and Early Holocene Tephras, Northern British Columbia

LATE-GLACIAL ALPINE GLACIER ADVANCE AND EARLY HOLOCENE TEPHRAS, NORTHERN BRITISH COLUMBIA Thomas Ryan Lakeman B.Sc., University of Alberta, 2004 THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF SCIENCE In the Department of Earth Sciences O Thomas Ryan Lakeman 2006 SIMON FRASER UNIVERSITY Fall 2006 All rights reserved. This work may not be reproduced, in whole or in part, by photocopy or other means, without permission of the author, except for scholarly, non-profit use. APPROVAL Name: Thomas Lakeman Degree: Master of Science Title of Thesis: Late-Glacial Alpine Glacier advance and early Holocene Tephras, Northern British Columbia Examining Committee: Chair: Dr. Derek Thorkelson , Professor, Department of Earth Sciences Dr. John Clague Senior Supervisor Professor, Department of Earth Sciences Dr. Brent Ward Supervisor Associate Professor, Department of Earth Sciences Dr. Brian Menounos Supervisor University of British Columbia Dr. Peter Bobrowsky External Examiner Geological Survey of Canada Date DefendedIApproved: November 10,2006 u~iv~~srnllSIMON FRASER brary DECLARATION OF PARTIAL COPYRIGHT LICENCE The author, whose copyright is declared on the title page of this work, has granted to Simon Fraser University the right to lend this thesis, project or extended essay to users of the Simon Fraser University Library, and to make partial or single copies only for such users or in response to a request from the library of any other university, or other educational institution, on its own behalf or for one of its users. The author has further granted permission to Simon Fraser University to keep or make a digital copy for use in its circulating collection (currently available to the public at the "Institutional Repository" link of the SFU Library website <www.lib.sfu.ca> at: <http:llir.lib.sfu.calhandlell8921112~)and, without changing the content, to translate the thesislproject or extended essays, if technically possible, to any medium or format for the purpose of preservation of the digital work. -

Arctic Grayling Synthesis Report

FWCP Arctic Grayling Synthesis Report Limiting Factors, Enhancement Potential, Conservation Status, and Critical Habitats for Arctic Grayling in the Williston Reservoir Watershed, and Information Gaps Limiting Potential Conservation and Enhancement Actions Mike Stamford,1 John Hagen,2 and Susanne Williamson3 April, 2017 Prepared for: Fish and Wildlife Compensation Program – Peace Region 9228 – 100th Avenue, Fort St. John, BC, V1J 1X7 Prepared with financial support of the Fish and Wildlife Compensation Program on behalf of its program partners BC Hydro, the Province of BC, Fisheries and Oceans Canada, First Nations and public stakeholders. ________________________________________________________________ 1 Stamford Environmental, 877 West Bay Rd, Gambier Island, BC, V0N 1V0; [email protected] 2 John Hagen and Associates, 330 Alward St., Prince George, BC, V2M 2E3; [email protected] 3 Ministry of Environment, 2000 South Ospika Blvd., Prince George; V2N 4W5; [email protected] EXECUTIVE SUMMARY FWCP strategic objectives. The FWCP Streams Action Plan (FWCP 2014) identifies two over-arching strategic objectives for the conservation and enhancement of Arctic Grayling and other priority fish species in the upper Peace Basin: 1. Maintain or improve the conservation status of Arctic Grayling populations. 2. Maintain or improve the integrity and productivity of Arctic Grayling habitats. This study was initiated by FWCP to evaluate the existing knowledge base relative to these strategic objectives, and fulfill objective 1b-1 of the Streams Action Plan: Review existing information (including provincial management plan), summarize status and trends of Arctic Graying and its habitats, undertake actions that are within the FWCP scope and lead directly to the development of conservation and enhancement actions, and develop a cost- effective monitoring program to assess status and trends. -

Williston Reservoir Watershed: Fish and Fish Habitat, Benthos, and Water Quality Data

WILLISTON RESERVOIR WATERSHED: FISH AND FISH HABITAT, BENTHOS, AND WATER QUALITY DATA A COMPENDIUM OF DATA SOURCES (1959 to 1998) T. D. French August 1999 PWFWCP Report No. 192 The Peace/Williston Fish & Wildlife Compensation Program is a cooperative venture of BC Hydro and the provincial fish and wildlife management agencies, supported by funding from BC Hydro. The Program was established to enhance and protect fish and wildlife resources affected by the construction of the W.A.C. Bennett and Peace Canyon dams on the Peace River, and the subsequent creation of the Williston and Dinosaur Reservoirs. Peace/Williston Fish and Wildlife Compensation Program, 1011 Fourth Ave. 3rd Floor, Prince George B.C. V2L 3H9 Website: www.bchydro.com/pwcp/ This report has been approved by the Peace/Williston Fish and Wildlife Compensation Program Fish Technical Committee. Citation: French T. D. 1999. Williston Reservoir Watershed: Fish and fish habitat, benthos, and water quality data. A Compendium of data sources 1959 to 1998). Peace/Williston Fish and Wildlife Compensation Program Report No. 292. 99pp plus appendices. Author(s): T. D. French Address(es): Salix Environmental Services, P.O. Box 1366, Prince George, BC, V2L 4V4 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I thank Bob Westcott (BC Hydro, Hudson’s Hope), Arnie Langston (PWFWCP, Prince George), Randy Zemlak (PWFWCP, Prince George), Brian Blackman (PWFWCP, Prince George), Nick Baccante (BCMELP, Fort St. John) and Rowena Rae (independent, Prince George) for reviewing the original draft of this report. Bob Westcott, Brian Blackman, Nick Baccante, Lynne Blouw (BCMELP, Prince George), Ben Kangasniemi (BCMELP, Victoria), Ted Zimmerman (BCMELP, Prince George) and Bruce Carmichael (BCMELP, Prince George) helped me locate historic and new Williston Watershed literature and data sources. -

Freshwater Atlas User Guide (PDF)

FRESHWATER WATER ATLAS USER GUIDE Contact: Malcolm Gray GeoBC Integrated Land Management Bureau P.O. Box 9355 Stn. Prov. Govt. Victoria, BC V8W 9M2 Document prepared by: Caslys Consulting Ltd. Unit 102A, 6683 Oldfield Road Saanichton, B.C., V8M 2A1 September 25, 2009 January 12, 2010 Freshwater Atlas – User Guide TABLE OF CONTENTS 1.0 WHAT IS THE FRESHWATER ATLAS? ................................................................................................. 1 1.1 Overview 1 1.2 Application Examples ........................................................................................................................ 3 1.2.1 Identifying a Feature by Name ........................................................................................................................ 3 1.2.2 Cartography ............................................................................................................................................................. 3 1.2.3 Inventory Frameworks ......................................................................................................................................... 3 1.2.4 Analysis ...................................................................................................................................................................... 5 2.0 WHAT TYPES OF DATA ARE IN THE FRESHWATER ATLAS? .............................................................. 7 2.1 Data Extent ........................................................................................................................................ -

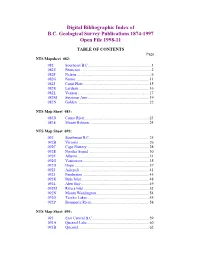

Digital Bibliographic Index of B.C. Geological Survey Publications 1874-1997 Open File 1998-11

Digital Bibliographic Index of B.C. Geological Survey Publications 1874-1997 Open File 1998-11 TABLE OF CONTENTS Page NTS Mapsheet 082: 082 Southeast B.C..............................................................1 082E Penticton.....................................................................2 082F Nelson.........................................................................6 082G Fernie........................................................................11 082J Canal Flats.................................................................15 082K Lardeau.....................................................................16 082L Vernon.......................................................................17 082M Seymour Arm............................................................19 082N Golden.......................................................................22 NTS Map Sheet 083: 083D Canoe River...............................................................23 083E Mount Robson...........................................................24 NTS Map Sheet 092: 092 Southwest B.C...........................................................25 092B Victoria.....................................................................26 092C Cape Flattery.............................................................28 092E Nootka Sound...........................................................30 092F Alberni.......................................................................31 092G Vancouver.................................................................35 -

British Columbia Mineral Exploration Review U

Province of British Columbia Ministry of Energy, Mines and Petroleum Resources Hon. Jack Davis, Minister BRITISH COLUMBIA * MINERAL EXPLORATION REVIEW U Information Circular 1990-1 Province of British Columbia Ministry of Energy, Mines and Petroleum Resources Hon. Jack Davis, Minister BRITISH COLUMBIA MINERAL EXPLORATION REVIEW Information Circular 1990-1 MINERAL RESOURCES DIVISION Geological Survey Branch British Columbia Cataloguing in Publication Data Main entry under title: British Columbia mineral exploration review. -- 1985- (Information circular, ISSN 0825-5431) Annual. Issuing body varies: 1985, Geological Branch; 1986- , Geological Survey Branch. Continues: British Columbia exploration review. ISSN 0828-6094 = British Columbia mineral exploration review 1. Prospecting - British Columbia - Periodicals. 2. Geology, Economic - British Columbia - Periodicals. 3. Mines and mineral resources - British Columbia - Periodicals. I. British Columbia. Geological Branch. 11. British Columbia. Geological Survey Branch. 111. Series: Information circular (British Columbia. Ministry of Energy, Mines and Petroleum Resources) TN270AlB74 622’.1’09711 Rev. Jan. 1988 VICTORIA BRITISH COLUMBIA CANADA JANUARY 1990 h wu_v .A. <Nh,*v.~.V.V.%u. .................................... .v.V. .............. __,............ ....,.... h......... *' .............. .....,... .... TABLE OF CONTENTS page Page WHAT IS NEW IN BRITISH COLUMBIA?.......... 1 Princeton .Tulameen ........................................... 45 Introduction .............................................................. -

State of the Muskwa-Kechika Report” and Reports on the Current Status of the Area’S Ecological Conservation, Economic Progress and Social Development, I.E

STATE OF THE MUSKWA -KECHIKA REPORT PREPARED FOR : MUSKWA -KECHIKA ADVISORY BOARD PREPARED BY : 1763 EAST 3RD AVE . VANCOUVER , BC V5N 1H3 WITH ASSISTANCE FROM : 212 – 1200 LYNN VALLEY RD. NORTH VANCOUVER , BC V7J 2A2 MAY 2008 Table of Contents 1. Executive Summary .............................................................................................................. 1 2. Introduction ........................................................................................................................... 4 2.1 Report Purpose ............................................................................................................................ 4 2.2 Approach and Data Sources ........................................................................................................ 4 3. Muskwa-Kechika Management Area ................................................................................... 7 3.1 Overview of Muskwa-Kechika Management Area....................................................................... 7 3.2 Vision ........................................................................................................................................... 9 3.3 Legislation ..................................................................................................................................10 3.4 Governance ................................................................................................................................12 4. Ecological Conservation ...................................................................................................