Global Media Journal - Australian Edition - 5:1 2011 1 of 3 of the Most Valuable Contributions of the Book

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

ANNUAL REPORT 2019 Revellers at New Year’S Eve 2018 – the Night Is Yours

AUSTRALIAN BROADCASTING CORPORATION ANNUAL REPORT 2019 Revellers at New Year’s Eve 2018 – The Night is Yours. Image: Jared Leibowtiz Cover: Dianne Appleby, Yawuru Cultural Leader, and her grandson Zeke 11 September 2019 The Hon Paul Fletcher MP Minister for Communications, Cyber Safety and the Arts Parliament House Canberra ACT 2600 Dear Minister The Board of the Australian Broadcasting Corporation is pleased to present its Annual Report for the year ended 30 June 2019. The report was prepared for section 46 of the Public Governance, Performance and Accountability Act 2013, in accordance with the requirements of that Act and the Australian Broadcasting Corporation Act 1983. It was approved by the Board on 11 September 2019 and provides a comprehensive review of the ABC’s performance and delivery in line with its Charter remit. The ABC continues to be the home and source of Australian stories, told across the nation and to the world. The Corporation’s commitment to innovation in both storytelling and broadcast delivery is stronger than ever, as the needs of its audiences rapidly evolve in line with technological change. Australians expect an independent, accessible public broadcasting service which produces quality drama, comedy and specialist content, entertaining and educational children’s programming, stories of local lives and issues, and news and current affairs coverage that holds power to account and contributes to a healthy democratic process. The ABC is proud to provide such a service. The ABC is truly Yours. Sincerely, Ita Buttrose AC OBE Chair Letter to the Minister iii ABC Radio Melbourne Drive presenter Raf Epstein. -

Download Program

Festival Guests Festival Information Sponsors Amanda Anastasi is an award-winning poet writer of the The Treehouse series and the in Residence at Melbourne University, Janet How to Book Festival Venues Major Partners Williamstown Literary whose work ranges from the introspective to BUM trilogy. Clarke Hall. willy All events held on Saturday 13 June the socio-political. Gideon Haigh has been an independent Susan Pyke teaches with the University of For detailed descriptions of sessions, David Astle is the Dictionary Guy on Letters journalist for almost 30 years. Melbourne, and her poetry, short stories and presenters and to book tickets, visit and Sunday 14 June are located at either the Williamstown Town Hall www.willylitfest.org.au or phone the ( and Numbers (SBS) and well-known crossword John Harms is a writer, publisher, broadcaster associative essays have appeared in various Festival lit compiler. and historian who appears on Offsiders (ABC) journals. Box Office on 9932 4074. or the Williamstown Library. ‘’ Kate Atkinson is an actor and one of the and runs footyalmanac.com.au Jane Rawson was formerly the Environment Book before midnight, Sunday 24 May Both are located at 104 Ferguson original founders of Actors for Refugees. & Energy Editor for news website, The Catherine Harris is an award-winning writer 2015 for special early bird pricing. Street, Williamstown. Please check 13 and 14 June 2015 fest Matt Blackwood has won multiple awards for and author of The Family Men. Conversation. She is the author of the novel, A Wrong Turn at the Office of Unmade Lists. your ticket for room details. -

Is the Government Listening? Now That the Uproar and Shouting About Alleged Bias Has Died Down, There Is Only One Issue Paramount for the ABC - Funding

Friends of the ABC (NSW) Inc. qu a rt e r ly news l e t t e r Se ptember 2005 Vol 15, No. 3 in c o rp o rat i n g ba ck g round briefing na tional magaz i n e up d a t e friends of the abc Is the Government listening? Now that the uproar and shouting about alleged bias has died down, there is only one issue paramount for the ABC - funding. The corporation has not been backward putting its case forward - notably the collapse of drama production to just 20 hours per annum. In the Melbourne Age, Director of ABC TV Sandra Levy referred to circumstances as "critical and tragic." around, low-cost end - we've pretty "We have all those important well done everything we can." obligations to indigenous programs, religious programs, science, arts, Costs up children’s programs ... things that the dramatically commercial networks don't, and yet Once the launch pad for great we probably battle along with about Australian drama, revelations that the a quarter of what they spend in a ABC's drama output has dwindled year - the disproportion is massive." from 100 hours four years ago to just Ms Levy's concerns have been 14 hours this year have received a lot echoed by managing director Russell of media attention. Balding and chairman Donald Ms Levy estimates that an hour McDonald, who have spent the past could cost anywhere from $500,000 few weeks publicly lamenting the to $2 million, 10 to 50 times more gravity of the funding crisis. -

Ministerial Advisers in the Australian System of Responsible Government∗

Between Law and Convention: Yee-Fui Ng Ministerial Advisers in the Australian System of Responsible Government∗ It is hard to feel sorry for politicians. Yet it is undeniable that a modern day minister has many different responsibilities, including managing policy, the media and political issues. Ministers also have to mediate with and appease various stakeholders, including constituents and interest groups. Within the political structure they have to work cooperatively with their prime minister, members of parliament and their political party. It is impossible for one person to shoulder all these tasks single-handedly. Newly elected ministers are faced with a vast and bewildering bureaucracy inherited from the previous government. Although the public service is supposed to be impartial, ministers may not be willing to trust the bureaucracy when a few moments ago it was serving their opponents. Understandably, ministers have the desire to have partisan advisers whom they trust to advise them. This has led to the rise of the ministerial adviser. Ministerial advisers are personally appointed by ministers and work out of the ministers’ private offices. In the last 40 years, ministerial advisers have become an integral part of the political landscape. It all started with the informal ‘kitchen cabinets’, where a small group of the minister’s trusted friends and advisers gathered around the kitchen table to discuss political strategies. This has since become formalised and institutionalised into the role of the partisan ministerial adviser as distinct from the impartial public service. The number of Commonwealth ministerial staff increased from 155 in 1972 to 423 in 2015—an increase of 173 per cent. -

ABC NEWS Program Guide: Week 3 Index

1 | P a g e ABC NEWS Program Guide: Week 3 Index Index Program Guide .............................................................................................................................................................. 3 Sunday, 10 January 2021 ...................................................................................................................................... 3 Monday, 11 January 2021 ..................................................................................................................................... 9 Tuesday, 12 January 2021 ................................................................................................................................... 12 Wednesday, 13 January 2021 ............................................................................................................................. 15 Thursday, 14 January 2021 ................................................................................................................................. 18 Friday, 15 January 2021 ...................................................................................................................................... 21 Saturday, 16 January 2021 .................................................................................................................................. 24 2 | P a g e ABC NEWS Program Guide: Week 3 Sunday 10 January 2021 Program Guide Sunday, 10 January 2021 6:00am ABC News Update The top stories from ABC News, updating you on the latest headlines and the overnight -

Tanner Dumps on PM

The Sunday Telegraph April 24, 2011 12:00AM Tanner dumps on PM JULIA Gillard is fortunate the next election is two years away. Policy quicksand is dragging the Labor Government down in every direction: asylum seekers, carbon tax, the national broadband network, defence reform and preparations for a killer budget. Disastrous Labor polling shows voters think the Government gets everything wrong. Senior press-gallery commentators are virtually writing off Ms Gillard's chances. And now, a former member of inner-Cabinet's "gang of four", Lindsay Tanner, has pole-axed Ms Gillard. In his upcoming memoir, Mr Tanner, who quit in Ms Gillard's first Question Time as Prime Minister last year, writes: "Whether I like it or not, I have spent much of my adult life in an entertainment industry. "My craft as a politician was swamped by such values. Modern politics now resembles a Hollywood blockbuster: all special effects and no plot." He takes veiled digs at ex-colleagues, in the guise of a critique of "shallow" media coverage: Julia Gillard dyes her hair red, Queensland Premier Anna Bligh has Botox, Kevin Rudd once nibbled his own ear-wax, Mark Latham had "man-boobs". This is a damaging book from a man who makes no secret of his bitterness. Mr Tanner has been at odds with Ms Gillard since their student days. He has publicly expressed distaste for modern Labor since 2003, when Mr Latham became leader. When Mr Rudd was rolled, Mr Tanner retired, leaving the Greens to take his seat of Melbourne. Now, as Ms Gillard grapples with the unwieldy Green-independent balance of power, Mr Tanner throws bombs from the sideline. -

Comparing the Dynamics of Party Leadership Survival in Britain and Australia: Brown, Rudd and Gillard

This is a repository copy of Comparing the dynamics of party leadership survival in Britain and Australia: Brown, Rudd and Gillard. White Rose Research Online URL for this paper: http://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/82697/ Version: Accepted Version Article: Heppell, T and Bennister, M (2015) Comparing the dynamics of party leadership survival in Britain and Australia: Brown, Rudd and Gillard. Government and Opposition, FirstV. 1 - 26. ISSN 1477-7053 https://doi.org/10.1017/gov.2014.31 Reuse Unless indicated otherwise, fulltext items are protected by copyright with all rights reserved. The copyright exception in section 29 of the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988 allows the making of a single copy solely for the purpose of non-commercial research or private study within the limits of fair dealing. The publisher or other rights-holder may allow further reproduction and re-use of this version - refer to the White Rose Research Online record for this item. Where records identify the publisher as the copyright holder, users can verify any specific terms of use on the publisher’s website. Takedown If you consider content in White Rose Research Online to be in breach of UK law, please notify us by emailing [email protected] including the URL of the record and the reason for the withdrawal request. [email protected] https://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/ Comparing the Dynamics of Party Leadership Survival in Britain and Australia: Brown, Rudd and Gillard Abstract This article examines the interaction between the respective party structures of the Australian Labor Party and the British Labour Party as a means of assessing the strategic options facing aspiring challengers for the party leadership. -

Budget 2017: ABC Coverage on TV, Iview, Radio and Online

Media Release: 05.05.17 Budget 2017: ABC Coverage on TV, iview, radio and online abc.net.au/news The 2017 Federal Budget will be handed down on Tuesday May 9 and the ABC has the best independent coverage on all platforms. We’ll have the first interview with Treasurer Scott Morrison, as well as in-depth analysis and expert commentary from the ABC’s leading political and business teams. What does Budget 2017 mean for you? Know the numbers, the politics, and the impact with ABC NEWS. Tuesday, 9 May – BUDGET DAY TELEVISION – ABC, the ABC NEWS channel & iview The Drum - 5.30pm on ABC & iview / 6.30pm AEST on the ABC NEWS channel As the press gallery bunkers down in the budget media lock-up, host John Barron and a panel of experts will count down to Budget 2017 and preview what to expect. ABC NEWS - 7pm on ABC & iview The news of the day and the lead up to the Federal Treasurer’s Budget speech. ABC NEWS BUDGET 2017 SPECIAL - on ABC, the ABC NEWS channel, iview, ABC NEWS online and simulcast live on the ABC News Facebook page. Leigh Sales hosts the ABC NEWS Budget 2017 special with Political Editor Chris Uhlmann live from Parliament House in Canberra. At 7:30pm AEST the Federal Treasurer Scott Morrison will deliver his second Federal Budget speech live from the House of Representatives. Just after 8pm, Federal Treasurer Scott Morrison will join Leigh Sales for his first interview of the night, followed by the response from the Opposition’s Shadow Treasurer Chris Bowen. -

Parliamentary Debates (Hansard)

PARLIAMENT OF VICTORIA PARLIAMENTARY DEBATES (HANSARD) LEGISLATIVE ASSEMBLY FIFTY-FIFTH PARLIAMENT FIRST SESSION 14 October 2003 (extract from Book 4) Internet: www.parliament.vic.gov.au/downloadhansard By authority of the Victorian Government Printer The Governor JOHN LANDY, AC, MBE The Lieutenant-Governor Lady SOUTHEY, AM The Ministry Premier and Minister for Multicultural Affairs ....................... The Hon. S. P. Bracks, MP Deputy Premier, Minister for Environment, Minister for Water and Minister for Victorian Communities.............................. The Hon. J. W. Thwaites, MP Minister for Finance and Minister for Consumer Affairs............... The Hon. J. Lenders, MLC Minister for Education Services and Minister for Employment and Youth Affairs....................................................... The Hon. J. M. Allan, MP Minister for Transport and Minister for Major Projects................ The Hon. P. Batchelor, MP Minister for Local Government and Minister for Housing.............. The Hon. C. C. Broad, MLC Treasurer, Minister for Innovation and Minister for State and Regional Development......................................... The Hon. J. M. Brumby, MP Minister for Agriculture........................................... The Hon. R. G. Cameron, MP Minister for Planning, Minister for the Arts and Minister for Women’s Affairs................................... The Hon. M. E. Delahunty, MP Minister for Community Services.................................. The Hon. S. M. Garbutt, MP Minister for Police and Emergency Services -

Social Media Thought Leaders Updated for the 45Th Parliament 31 August 2016 This Barton Deakin Brief Lists

Barton Deakin Brief: Social Media Thought Leaders Updated for the 45th Parliament 31 August 2016 This Barton Deakin Brief lists individuals and institutions on Twitter relevant to policy and political developments in the federal government domain. These institutions and individuals either break policy-political news or contribute in some form to “the conversation” at national level. Being on this list does not, of course, imply endorsement from Barton Deakin. This Brief is organised by categories that correspond generally to portfolio areas, followed by categories such as media, industry groups and political/policy commentators. This is a “living” document, and will be amended online to ensure ongoing relevance. We recognise that we will have missed relevant entities, so suggestions for inclusions are welcome, and will be assessed for suitability. How to use: If you are a Twitter user, you can either click on the link to take you to the author’s Twitter page (where you can choose to Follow), or if you would like to follow multiple people in a category you can click on the category “List”, and then click “Subscribe” to import that list as a whole. If you are not a Twitter user, you can still observe an author’s Tweets by simply clicking the link on this page. To jump a particular List, click the link in the Table of Contents. Barton Deakin Pty. Ltd. Suite 17, Level 2, 16 National Cct, Barton, ACT, 2600. T: +61 2 6108 4535 www.bartondeakin.com ACN 140 067 287. An STW Group Company. SYDNEY/MELBOURNE/CANBERRA/BRISBANE/PERTH/WELLINGTON/HOBART/DARWIN -

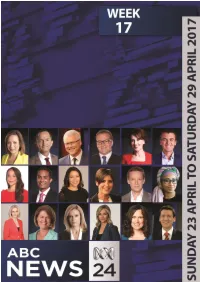

ABC News 24 Program Schedule

1 | P a g e ABCNEWS24 Program Guide: National: Week 17 Index Index Program Guide .............................................................................................................................................................. 3 Sunday, 23 April 2017 ........................................................................................................................................... 3 Monday, 24 April 2017 .......................................................................................................................................... 9 Tuesday, 25 April 2017 ........................................................................................................................................ 14 Wednesday, 26 April 2017 .................................................................................................................................. 17 Thursday, 27 April 2017 ...................................................................................................................................... 20 Friday, 28 April 2017 ........................................................................................................................................... 23 Saturday, 29 April 2017 ....................................................................................................................................... 26 Marketing Contacts ..................................................................................................................................................... 31 2 | P a -

Built Environment Meets Parliament’ Summit, Canberra

1 of 8 FINANCE AND GOVERNANCE COMMITTEE Agenda Item 6.3 REPORT 13 October 2009 COUNCILLOR CLARKE POST TRAVEL REPORT ‘BUILT ENVIRONMENT MEETS PARLIAMENT’ SUMMIT, CANBERRA Report by Councillor Peter Clarke Purpose 1. To report to the Finance and Governance Committee on the travel undertaken by Cr Peter Clarke to Canberra to participate in the ‘Built Environment Meets Parliament’ (BEMP) Summit, Parliament House, Canberra on 12 August 2009. Recommendation 2. That the Finance and Governance Committee note this report and the incorporated summary of benefits and outcomes. Background 3. Cr Clarke’s participation in the BEMP 09 Summit was approved by the Lord Mayor on 4 August in accordance with the Councillor Expenses and Resources Guidelines. Due to time constraints, the proposal was unable to be submitted to the Finance and Governance Committee as the next meeting of the Committee was scheduled for 11 August which was the day before the Summit. Key Issues Details of Travel 4. Cr Clarke attended the BEMP 2009 Summit on Wednesday 12 August. 5. The Summit was held in the Theatre, Parliament House, Canberra from 8.30am – 5pm. BEMP 2009 was attended by 200 delegates including architects, planners, engineers, developers, key government department representatives, ministers, shadow ministers, members of parliament and parliamentary advisors. 6. The annual BEMP Summit is co-hosted by the following organisations: 6.1. Association of Consulting Engineers, Australia; 6.2. Australian Institute of Architects; 6.3. Green Building Council of Australia; 6.4. The Planning Institute of Australia; and 6.5. Property Council of Australia. 7. A copy of the Summit program is included at Attachment 1.