Final Assessment of CEPF Investment in the Indo-Burma Hotspot 2008-2013

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Spatial Distribution and Historical Dynamics of Threatened Conifers of the Dalat Plateau, Vietnam

SPATIAL DISTRIBUTION AND HISTORICAL DYNAMICS OF THREATENED CONIFERS OF THE DALAT PLATEAU, VIETNAM A thesis Presented to The Faculty of the Graduate School At the University of Missouri In Partial Fulfillment Of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Arts By TRANG THI THU TRAN Dr. C. Mark Cowell, Thesis Supervisor MAY 2011 The undersigned, appointed by the dean of the Graduate School, have examined the thesis entitled SPATIAL DISTRIBUTION AND HISTORICAL DYNAMICS OF THREATENED CONIFERS OF THE DALAT PLATEAU, VIETNAM Presented by Trang Thi Thu Tran A candidate for the degree of Master of Arts of Geography And hereby certify that, in their opinion, it is worthy of acceptance. Professor C. Mark Cowell Professor Cuizhen (Susan) Wang Professor Mark Morgan ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS This research project would not have been possible without the support of many people. The author wishes to express gratitude to her supervisor, Prof. Dr. Mark Cowell who was abundantly helpful and offered invaluable assistance, support, and guidance. My heartfelt thanks also go to the members of supervisory committees, Assoc. Prof. Dr. Cuizhen (Susan) Wang and Prof. Mark Morgan without their knowledge and assistance this study would not have been successful. I also wish to thank the staff of the Vietnam Initiatives Group, particularly to Prof. Joseph Hobbs, Prof. Jerry Nelson, and Sang S. Kim for their encouragement and support through the duration of my studies. I also extend thanks to the Conservation Leadership Programme (aka BP Conservation Programme) and Rufford Small Grands for their financial support for the field work. Deepest gratitude is also due to Sub-Institute of Ecology Resources and Environmental Studies (SIERES) of the Institute of Tropical Biology (ITB) Vietnam, particularly to Prof. -

North-South Expressway Master Plan Final Report

JAPAN INTERNATIONAL COOPERATION AGENCY (JICA) MINISTRY OF TRANSPORT, VIETNAM THE COMPREHENSIVE STUDY ON THE SUSTAINABLE DEVELOPMENT OF TRANSPORT SYSTEM IN VIETNAM (VITRANSS 2) North-South Expressway Master Plan Final Report May 2010 ALMEC CORPORATION ORIENTAL CONSULTANTS CO. LTD. NIPPON KOEI CO. LTD. JAPAN INTERNATIONAL COOPERATION AGENCY (JICA) MINISTRY OF TRANSPORT, VIETNAM THE COMPREHENSIVE STUDY ON THE SUSTAINABLE DEVELOPMENT OF TRANSPORT SYSTEM IN VIETNAM (VITRANSS 2) North-South Expressway Master Plan Final Report May 2010 ALMEC CORPORATION ORIENTAL CONSULTANTS CO. LTD. NIPPON KOEI CO. LTD. Exchange Rate Used in the Report USD 1 = JPY 110 = VND 17,000 (Average Rate in 2008) PREFACE In response to the request from the Government of the Socialist Republic of Vietnam, the Government of Japan decided to conduct the Comprehensive Study on the Sustainable Development of Transport System in Vietnam (VITRANSS2) and entrusted the program to the Japan International cooperation Agency (JICA) JICA dispatched a team to Vietnam between November 2007 and May 2010, which was headed by Mr. IWATA Shizuo of ALMEC Corporation and consisted of ALMEC Corporation, Oriental Consultants Co., Ltd., and Nippon Koei Co., Ltd. In the cooperation with the Vietnamese Counterpart Team, the JICA Study Team conducted the study. It also held a series of discussions with the relevant officials of the Government of Vietnam. Upon returning to Japan, the Team duly finalized the study and delivered this report. I hope that this report will contribute to the sustainable development of transport system and Vietnam and to the enhancement of friendly relations between the two countries. Finally, I wish to express my sincere appreciation to the officials of the Government of Vietnam for their close cooperation. -

The Turtle Free

FREE THE TURTLE PDF Cynthia Rylant,Preston McDaniels | 48 pages | 01 Apr 2006 | Beach Lane Books | 9780689863127 | English | New York, NY, United Kingdom Turtle (submersible) - Wikipedia They scored their biggest and best-known hit in with the song " Happy Together " [2]. The band broke up in Adhering to the prevailing musical trend, they rebranded themselves as a folk rock group under the name The Tyrtlesan intentionally stylized misspelling inspired by The The Turtle and The Beatles. However, the trendy spelling did not survive long. As with the Byrds, the Turtles achieved breakthrough success with a cover of a Bob The Turtle song. One single, the tough "Outside Chance", written by Warren Zevon and featuring guitar work in the The Turtle of The Beatles' " Taxman ", did not chart. At the start ofdrummer Don Murray and bassist Chuck Portz quit the group. The first of several key Turtles singles co-written by Garry Bonner and Alan Gordon" Happy Together " had already been rejected by countless performers. The Turtles' only No. An album of the same name followed and peaked at No. Impressed by Chip Douglas's studio arrangements, Michael Nesmith approached him after a Turtles show at the Whisky a Go Go and invited him to become The Monkees ' new producer, as that band wanted to break out of their "manufactured" studio mold. Douglas was replaced by Jim Pons on bass. Nineteen sixty-seven proved to be the Turtles' most successful year on the music charts. Both 45s signaled a certain shift in the band's style. Golden Hits was released later The Turtle year, charting in the top The similar album covers for The Turtle Turtles! Inrhythm guitarist Jim Tucker left the band citing the pressure of touring and recording new material. -

Assessement of Biodiversity and NTFP Status in BCI Project Areas

APPENDIX 4 Assessment of Biodiversity Values in BCI project Areas Part I. Introduction of BCI project area and its biodiversity status 1.1. Physical characteristics BCI area is situated in the Priority Central Annamite Landscape ( Landscape CA1)( or Central Truong Son Landscape), it is a geomorphological entity within the Greater Truong Son Global 200 Ecoregion of the FLMEC of Greater Annamite Ecoregion in Global 200 of WWF . were provisionally delineated at the Ecoregion-based Conservation in the Forests of the Mekong Biological Assessment Workshop, held inPhnom Penh in March 2000. And Landcape CA1 will be introduced as follows: Priority Landscape CA1 is. The priority landscape encompasses the central section of the main Annamite chain, together with associated foothills to the west and east (Map 1). The boundaries of Priority Landscape CA1 were delineated according to geomorphological criteria in preference to biogeographical criteria for a number of reasons. Firstly, while the ranges of a number of taxa broadly define the priority landscape, there is insufficient congruence in their known distributions for the boundaries to be precisely delineated. Secondly, there is insufficient information available about the known distribution and habitat requirements of taxa that might be used to delineate the priority landscape. Thirdly, the concept of a geomorphologically delineated landscape is more meaningful to decision makers and donors. Finally, a geomorphologically delineated landscape is not constrained by anthropogenic changes in habitat condition and extent, and, therefore, presents a vision for the future and an objective for habitat restoration efforts. The area referred to as the Greater Truong Son in this document was considered by Vidal (1960) to comprise parts of two distinct geomorphological units: the Annamite chain, stretching from Xieng Khoang province in Lao P.D.R. -

A Publication of the Turtle Survival Alliance 55 Visit Us Online At

TurtleA PUBLICATION OF THE Survival TURTLE SURVIVAL ALLIANCE 2015 TSA EUROPE Captive Breeding Critical to Saving the Highly Endangered Vietnamese Pond Turtle (Mauremys annamensis) Henk Zwartepoorte, Herbert Becker, Elmar Meier, Martina Raffel & Tim McCormack The Vietnamese Pond Turtle is not a particularly attractive or colorful species, so they were not very popular with private owners and zoos. Be- lieved extinct as recently as 2006, their fortunate survival now depends on captive breeding efforts to increase their numbers in the wild. Serious scientiic inquiry was initiated after it was discovered that individual specimens of M. annamensis were occasionally offered for sale in Asian animal markets. Field research and local interviews revealed that the species was not ex- tinct, and eventually discovered the origin of the market turtles. A wild, residential population was discovered in Central Vietnam within a distant and isolated area of the Quang Nam Province. Shortly afterwards, Vietnamese authorities began conservation efforts to protect the species with enthusiastic support from leading European zoos. A plan was developed whereby Vietnamese Pond Turtles hatched in Europe would be made available for a reintroduction project in Vietnam. The project’s plan requires inding out how many A juvenile M. annamensis in the wild – still a rarity. animals are left in the wild, where they live, and how these areas can be protected. The plan Association for Zoos and Aquariums (EAZA) The implementation of the EAZA studbook also includes the important goal of gaining local discussed how the breeding of the Vietnamese took longer than expected, so there was over- community support for reintroduction of M. -

PDF File Containing Table of Lengths and Thicknesses of Turtle Shells And

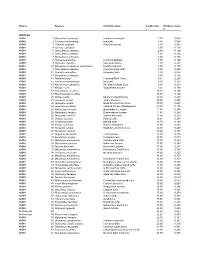

Source Species Common name length (cm) thickness (cm) L t TURTLES AMNH 1 Sternotherus odoratus common musk turtle 2.30 0.089 AMNH 2 Clemmys muhlenbergi bug turtle 3.80 0.069 AMNH 3 Chersina angulata Angulate tortoise 3.90 0.050 AMNH 4 Testudo carbonera 6.97 0.130 AMNH 5 Sternotherus oderatus 6.99 0.160 AMNH 6 Sternotherus oderatus 7.00 0.165 AMNH 7 Sternotherus oderatus 7.00 0.165 AMNH 8 Homopus areolatus Common padloper 7.95 0.100 AMNH 9 Homopus signatus Speckled tortoise 7.98 0.231 AMNH 10 Kinosternon subrabum steinochneri Florida mud turtle 8.90 0.178 AMNH 11 Sternotherus oderatus Common musk turtle 8.98 0.290 AMNH 12 Chelydra serpentina Snapping turtle 8.98 0.076 AMNH 13 Sternotherus oderatus 9.00 0.168 AMNH 14 Hardella thurgi Crowned River Turtle 9.04 0.263 AMNH 15 Clemmys muhlenbergii Bog turtle 9.09 0.231 AMNH 16 Kinosternon subrubrum The Eastern Mud Turtle 9.10 0.253 AMNH 17 Kinixys crosa hinged-back tortoise 9.34 0.160 AMNH 18 Peamobates oculifers 10.17 0.140 AMNH 19 Peammobates oculifera 10.27 0.140 AMNH 20 Kinixys spekii Speke's hinged tortoise 10.30 0.201 AMNH 21 Terrapene ornata ornate box turtle 10.30 0.406 AMNH 22 Terrapene ornata North American box turtle 10.76 0.257 AMNH 23 Geochelone radiata radiated tortoise (Madagascar) 10.80 0.155 AMNH 24 Malaclemys terrapin diamondback terrapin 11.40 0.295 AMNH 25 Malaclemys terrapin Diamondback terrapin 11.58 0.264 AMNH 26 Terrapene carolina eastern box turtle 11.80 0.259 AMNH 27 Chrysemys picta Painted turtle 12.21 0.267 AMNH 28 Chrysemys picta painted turtle 12.70 0.168 AMNH 29 -

The IUCN Red List of Threatened Speciestm

Species 2014 Annual ReportSpecies the Species of 2014 Survival Commission and the Global Species Programme Species ISSUE 56 2014 Annual Report of the Species Survival Commission and the Global Species Programme • 2014 Spotlight on High-level Interventions IUCN SSC • IUCN Red List at 50 • Specialist Group Reports Ethiopian Wolf (Canis simensis), Endangered. © Martin Harvey Muhammad Yazid Muhammad © Amazing Species: Bleeding Toad The Bleeding Toad, Leptophryne cruentata, is listed as Critically Endangered on The IUCN Red List of Threatened SpeciesTM. It is endemic to West Java, Indonesia, specifically around Mount Gede, Mount Pangaro and south of Sukabumi. The Bleeding Toad’s scientific name, cruentata, is from the Latin word meaning “bleeding” because of the frog’s overall reddish-purple appearance and blood-red and yellow marbling on its back. Geographical range The population declined drastically after the eruption of Mount Galunggung in 1987. It is Knowledge believed that other declining factors may be habitat alteration, loss, and fragmentation. Experts Although the lethal chytrid fungus, responsible for devastating declines (and possible Get Involved extinctions) in amphibian populations globally, has not been recorded in this area, the sudden decline in a creekside population is reminiscent of declines in similar amphibian species due to the presence of this pathogen. Only one individual Bleeding Toad was sighted from 1990 to 2003. Part of the range of Bleeding Toad is located in Gunung Gede Pangrango National Park. Future conservation actions should include population surveys and possible captive breeding plans. The production of the IUCN Red List of Threatened Species™ is made possible through the IUCN Red List Partnership. -

Executive Director Report

CEPF/DC16/5 Critical Ecosystem Partnership Fund Sixteenth Meeting of the Donor Council Conservation International 2011 Crystal Drive, Arlington, Virginia 15 January 2010 8 a.m. – 11 a.m. EST Executive Director Report For Information Only: The Acting Executive Director will highlight key developments since the Fifteenth Meeting of the Donor Council on 9 September 2009. For information, a report highlighting the following activities since that date is attached: Partnership Highlights Featured New Grants Highlights from the Field Approved Grants (15 August 2009 – 1 December 2009) A financial summary is also included. 1 Program Overview Hotspot strategies implemented: 18 Countries and territories covered within those hotspots: 51 Partners supported: 1,500+ Committed grants: $116 million Amount leveraged by those grants: $222 million Critical Ecosystem Partnership Fund Summary Fund Statement As of September 30, 2009 Revenue Cumulative Grants and Contributions $210,386,650 Gain (Loss) on Foreign Exchange 1,888,006 Interest Earned 1,956,822 Total Revenue 214,231,479 Expenses Grants 116,111,639 Ecosystem Profile Preparation 7,576,812 External Evaluation and Compliance Audit 344,653 Operations 20,005,668 Total Expenses 144,038,772 $70,192,707 FUND BALANCE AT THE END OF THE PERIOD CONSISTING OF: Cash Net of Amount Due to/from CI $33,654,669 Accounts Receivable 51,873,558 Grants Payable (15,335,521) Fund balance at end of the period $70,192,707 2 Critical Ecosystem Partnership Fund Summary Fund Statement As of September 30, 2009 Cumulative Revenue -

Karyotype and Idiogram of Indian Hog Deer (Hyelaphus Porcinus) by Conventional Staining, GTG-, High-Resolution and Ag-NOR Banding Techniques

© 2017 The Japan Mendel Society Cytologia 82(3): 227–233 Karyotype and Idiogram of Indian Hog Deer (Hyelaphus porcinus) by Conventional Staining, GTG-, High-Resolution and Ag-NOR Banding Techniques Krit Pinthong1, Alongklod Tanomtong2*, Hathaipat Khongcharoensuk2, Somkid Chaiphech3, Sukjai Rattanayuvakorn4 and Praween Supanuam5 1 Department of Fundamental Science, Faculty of Science and Technology, Surindra Rajabhat University, Surin, Muang 32000, Thailand 2 Toxic Substances in Livestock and Aquatic Animals Research Group, Department of Biology, Faculty of Science, Khon Kaen University, Khon Kaen, Muang 40002, Thailand 3 Department of Animal Science, Rajamangala University of Technology Srivijaya Nakhonsrithammarat Campus, Nakhonsrithammarat, Thungyai 80240, Thailand 4 Department of Science and Mathematics, Faculty of Agriculture and Technology, Rajamangala University of Technology Isan, Surin Campus, Surin, Muang 32000, Thailand 5 Biology Program, Faculty of Science, Ubon Ratchathani Rajabhat University, Ubon Ratchathani, Muang 34000, Thailand Received April 19, 2016; accepted January 20, 2017 Summary Standardized karyotype and idiogram of Indian hog deer (Hyelaphus porcinus) at Khon Kaen Zoo, Thailand was explored. Blood samples were taken from two male and two female deer. After standard whole blood T-lymphocytes were cultured at 37°C for 72 h in presence of colchicine, metaphase spreads were per- formed on microscopic slides and air-dried. Conventional staining, GTG-, high-resolution and Ag-NOR banding techniques were applied to stain the chromosome. The results show that the diploid chromosome number of H. porcinus was 2n=68, the fundamental number (NF) was 70 in both males and females. The types of autosomes observed were 6 large telocentric, 18 medium telocentric and 42 small telocentric chromosomes. -

Detailed Species Accounts from The

Threatened Birds of Asia: The BirdLife International Red Data Book Editors N. J. COLLAR (Editor-in-chief), A. V. ANDREEV, S. CHAN, M. J. CROSBY, S. SUBRAMANYA and J. A. TOBIAS Maps by RUDYANTO and M. J. CROSBY Principal compilers and data contributors ■ BANGLADESH P. Thompson ■ BHUTAN R. Pradhan; C. Inskipp, T. Inskipp ■ CAMBODIA Sun Hean; C. M. Poole ■ CHINA ■ MAINLAND CHINA Zheng Guangmei; Ding Changqing, Gao Wei, Gao Yuren, Li Fulai, Liu Naifa, Ma Zhijun, the late Tan Yaokuang, Wang Qishan, Xu Weishu, Yang Lan, Yu Zhiwei, Zhang Zhengwang. ■ HONG KONG Hong Kong Bird Watching Society (BirdLife Affiliate); H. F. Cheung; F. N. Y. Lock, C. K. W. Ma, Y. T. Yu. ■ TAIWAN Wild Bird Federation of Taiwan (BirdLife Partner); L. Liu Severinghaus; Chang Chin-lung, Chiang Ming-liang, Fang Woei-horng, Ho Yi-hsian, Hwang Kwang-yin, Lin Wei-yuan, Lin Wen-horn, Lo Hung-ren, Sha Chian-chung, Yau Cheng-teh. ■ INDIA Bombay Natural History Society (BirdLife Partner Designate) and Sálim Ali Centre for Ornithology and Natural History; L. Vijayan and V. S. Vijayan; S. Balachandran, R. Bhargava, P. C. Bhattacharjee, S. Bhupathy, A. Chaudhury, P. Gole, S. A. Hussain, R. Kaul, U. Lachungpa, R. Naroji, S. Pandey, A. Pittie, V. Prakash, A. Rahmani, P. Saikia, R. Sankaran, P. Singh, R. Sugathan, Zafar-ul Islam ■ INDONESIA BirdLife International Indonesia Country Programme; Ria Saryanthi; D. Agista, S. van Balen, Y. Cahyadin, R. F. A. Grimmett, F. R. Lambert, M. Poulsen, Rudyanto, I. Setiawan, C. Trainor ■ JAPAN Wild Bird Society of Japan (BirdLife Partner); Y. Fujimaki; Y. Kanai, H. -

Palaeozoology of Palawan Island, Philippines

Quaternary International 233 (2011) 142e158 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Quaternary International journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/quaint Palaeozoology of Palawan Island, Philippines Philip J. Piper a,d,*, Janine Ochoa b, Emil C. Robles a, Helen Lewis c, Victor Paz a,d a Archaeological Studies Program, Palma Hall, University of the Philippines, Diliman, Quezon City 1101, Philippines b Department of Anthropology, Palma Hall, University of the Philippines, Diliman, Quezon City 1101, Philippines c School of Archaeology, Newman Building, University College Dublin, Belfield, Dublin 4, Ireland d Research Associate, National Museum of the Philippines, P. Burgos Avenue, Manila, Philippines article info abstract Article history: Excavations at the Ille site in north Palawan have produced a large Terminal Pleistocene to Late Holocene Available online 16 August 2010 faunal assemblage. Derived both from the natural deaths of small mammals and the human hunting of large and intermediate game, the bone assemblage provides important new information about changes Keywords: in the composition and structure of the mammal community of Palawan over the last ca. 14 000 years. Palawan Island The Ille zooarchaeological record chronicles the terrestrial vertebrate fauna of the island, and the Palaeozoology disappearance of several large taxa since the end of the last glacial period due to environmental change Terminal Pleistocene and human impacts. Holocene Ó Mammal biodiversity 2010 Elsevier Ltd and INQUA. All rights reserved. Extinctions 1. Introduction Peninsular Malaysia, Java, Sumatra, Bali and Borneo, known as the Sunda Shelf (Mollengraaff, 1921). The study of archaeologically-derived animal bone assemblages The present-day environment of Palawan is broadly similar to provides invaluable information on the origin, dispersal and that of north Borneo, comprising lowland tropical rainforest to evolutionary history of different vertebrate communities. -

Amphibia: Anura: Rhacophoridae) from Laos: Molecular Consistency Versus Morphological Divergence Between Populations on Western and Eastern Side of the Annamite Range

Revue suisse de Zoologie (March 2017) 124(1): 47-51 ISSN 0035-418 First record of Gracixalus quyeti (Amphibia: Anura: Rhacophoridae) from Laos: molecular consistency versus morphological divergence between populations on western and eastern side of the Annamite Range Jennifer Egert1,7, Vinh Quang Luu1,2,7, Truong Quang Nguyen3, Minh Duc Le4,5,6, Michael Bonkowski1 & Thomas Ziegler1,7* 1 Institute of Zoology, Department of Terrestrial Ecology, University of Cologne, Zülpicher Strasse 47b, D-50674 Co- logne, Germany. E-mail: m.bonkowski@uni–koeln.de 2 Department of Wildlife, Faculty of Natural Resources and Environmental Management, Vietnam National University of Forestry, Xuan Mai, Chuong My, Hanoi, Vietnam. E-mail: [email protected] 3 Institute of Ecology and Biological Resources, Vietnam Academy of Science and Technology, 18 Hoang Quoc Viet, Hanoi, Vietnam. E-mail: [email protected] 4 Faculty of Environmental Sciences, Hanoi University of Science, Vietnam National University, 334 Nguyen Trai Road, Hanoi, Vietnam. E-mail: [email protected] 5 Centre for Natural Resources and Environmental Studies, Hanoi National University, 19 Le Thanh Tong, Hanoi, Viet- nam 6 Department of Herpetology, American Museum of Natural History, Central Park West at 79th Street, New York, New York 10024, USA 7 AG Zoologischer Garten Köln, Riehler Strasse 173, D-50735 Cologne, Germany. * Corresponding author, E-mail: [email protected] Abstract: We report the fi rst country record of the poorly known Gracixalus quyeti from Laos based on a recently collected specimen from Khammouane Province, central Laos. While the genetic analysis revealed nearly identical sequences, we found some differences in body ratios and color patterns among the specimen from Laos and the type series from the eastern side of the Annamite Range in Vietnam.