Companion Animal Practice (EJCAP), 21(1):13-21

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Using Cross-Species Vaccination Approaches to Counter Emerging

PERSPECTIVES adjuvant combinations to inform ‘go’ or ‘no- go’ decisions with regard to subsequent Using cross- species vaccination development of promising vaccine candidates (Fig. 1). approaches to counter emerging Most human infectious diseases have an animal origin, with more than 70% of infectious diseases emerging infectious diseases that affect humans initially crossing over from 8 George M. Warimwe , Michael J. Francis , Thomas A. Bowden, animals . Generating wider knowledge of how pathogens behave in animals can Samuel M. Thumbi and Bryan Charleston give indications of how to develop control Abstract | Since the initial use of vaccination in the eighteenth century, our strategies for human diseases, and vice understanding of human and animal immunology has greatly advanced and a wide versa. ‘One Health vaccinology’, a concept in which synergies in human and veterinary range of vaccine technologies and delivery systems have been developed. The immunology are identified and exploited COVID-19 pandemic response leveraged these innovations to enable rapid for vaccine development, could transform development of candidate vaccines within weeks of the viral genetic sequence our ability to control such emerging being made available. The development of vaccines to tackle emerging infectious infectious diseases. Due to similarities in diseases is a priority for the World Health Organization and other global entities. host–pathogen interactions, the natural More than 70% of emerging infectious diseases are acquired from animals, with animal hosts of a zoonotic infection may be the most appropriate model to study the some causing illness and death in both humans and the respective animal host. Yet disease and evaluate vaccine performance9. -

1 WORLD SMALL ANIMAL VETERINARY ASSOCIATION 2015 VACCINATION GUIDELINES for the OWNERS and BREEDERS of DOGS and CATS WSAVA Vacci

WORLD SMALL ANIMAL VETERINARY ASSOCIATION 2015 VACCINATION GUIDELINES FOR THE OWNERS AND BREEDERS OF DOGS AND CATS WSAVA Vaccination Guidelines Group M.J. Day (Chairman) School of Veterinary Sciences University of Bristol, United Kingdom M.C. Horzinek (Formerly) Department of Microbiology, Virology Division University of Utrecht, the Netherlands R.D. Schultz Department of Pathobiological Sciences University of Wisconsin-Madison, United States of America R. A. Squires James Cook University, Queensland, Australia 1 CONTENTS Introduction.......................................................................................3 Major infectious diseases of the dog and cat....................................5 The immune response......................................................................21 The principle of vaccination..............................................................29 Types of vaccine...............................................................................32 Drivers for change in vaccination protocols......................................35 Canine vaccination guidelines..........................................................37 Feline vaccination guidelines…………………………………………..46 Reporting of adverse reactions.........................................................51 Glossary of terms..............................................................................57 2 INTRODUCTION Vaccination of dogs and cats protects them from infections that may be lethal or cause serious disease. Vaccination is a safe and efficacious -

Review of Treatment of Generalised Tetanus in Dogs

Review of treatment of generalised REVIEW tetanus in dogs Fawcett A*a,b, Irwin Pc *Corresponding author aFaculty of Veterinary Science, University of Sydney, Sydney, New South Wales 2006, Australia; [email protected] bSydney Animal Hospitals Inner West, 1A Northumberland Avenue, Stanmore, New South Wales 2048, Australia cCollege of Veterinary Medicine, School of Veterinary and Life Sciences, Murdoch University, Murdoch, Western Australia 6150, Australia ABSTRACT This review paper investigates the published evidence for various therapeutic strategies commonly used in the management of generalised tetanus in dogs and cats. The level of the evidence for the efficacy of tetanus antitoxin administration, antimicrobial therapy, wound management and immunotherapy in companion animals was low, review articles citing case reports and small case series, rather than case-control, cohort studies or clinical trials. Untested extrapolation from published data on the treatment of people with tetanus frequently directs recommendations made for the management of tetanus in dogs and cats. There is a need for further studies and evidence-based guidelines for treatment of this condition in dogs and cats. Until then, clinical judgement is required by the veterinarian to determine appropriate treatment. Supportive care remains the mainstay of treatment. Aust Vet Pract 2014;44(1):574-578 INTRODUCTION Generalised tetanus is a rare but life-threatening neurologic disorder characterised by spastic paralysis, caused by tetanospasmin, a potent neurotoxin -

La Vaccination : Enjeux Et Polémiques En Médecine Humaine Et Vétérinaire

OATAO is an open access repository that collects the work of Toulouse researchers and makes it freely available over the web where possible This is an author’s version published in: https://oatao.univ-toulouse.fr/27564/ Fourcade, Océane . La vaccination : enjeux et polémiques en médecine humaine et vétérinaire. Thèse d'exercice, Médecine vétérinaire, Ecole Nationale Vétérinaire de Toulouse - ENVT, 2020, 178 p. Any correspondence concerning this service should be sent to the repository administrator: [email protected] ANNEE 2020 THESE : 2020 – TOU 3 – 4094 LA VACCINATION : ENJEUX ET POLEMIQUES EN MEDECINE HUMAINE ET VETERINAIRE _________________ THESE pour obtenir le grade de DOCTEUR VETERINAIRE DIPLOME D’ETAT présentée et soutenue publiquement devant l’Université Paul-Sabatier de Toulouse par FOURCADE Océane Née, le 27/09/1995 à TOULOUSE (31) ___________ Directrice de thèse : Mme Hélène DANIELS-TREFFANDER ___________ JURY PRESIDENT : M. Christophe PASQUIER Professeur à l’Université Paul-Sabatier de TOULOUSE ASSESSEURS : Mme Hélène DANIELS-TREFFANDER Maître de Conférences à l’Ecole Nationale Vétérinaire de TOULOUSE M. Stéphane BERTAGNOLI Professeur à l’Ecole Nationale Vétérinaire de TOULOUSE MEMBRE INVITEE : Mme Séverine BOULLIER Professeure à l’Ecole Nationale Vétérinaire de TOULOUSE Ministère de l'Agriculture et de l’Alimentation ECOLE NATIONALE VETERINAIRE DE TOULOUSE Directeur : Professeur Pierre SANS PROFESSEURS CLASSE EXCEPTIONNELLE M. BERTAGNOLI Stéphane, Pathologie infectieuse M. BOUSQUET-MELOU Alain, Pharmacologie - Thérapeutique Mme CHASTANT-MAILLARD Sylvie, Pathologie de la Reproduction Mme CLAUW Martine, Pharmacie-Toxicologie M. CONCORDET Didier, Mathématiques, Statistiques, Modélisation M DELVERDIER Maxence, Anatomie Pathologique M. ENJALBERT Francis, Alimentation Mme GAYRARD-TROY Véronique, Physiologie de la Reproduction, Endocrinologie M. -

Antibody Response to Canine Adenovirus-2 Virus Vaccination in Healthy Adult Dogs

viruses Article Antibody Response to Canine Adenovirus-2 Virus Vaccination in Healthy Adult Dogs Michèle Bergmann 1,*, Monika Freisl 1, Yury Zablotski 1, Stephanie Speck 2, Uwe Truyen 2 and Katrin Hartmann 1 1 Clinic of Small Animal Medicine, Centre for Clinical Veterinary Medicine, LMU Munich, Veterinaerstrasse 13, 80539 Munich, Germany; [email protected] (M.F.); [email protected] (Y.Z.); [email protected] (K.H.) 2 Institute of Animal Hygiene and Veterinary Public Health, University of Leipzig, An den Tierkliniken 1, 04103 Leipzig, Germany; [email protected] (S.S.); [email protected] (U.T.) * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +49-2180-2651 Received: 27 August 2020; Accepted: 16 October 2020; Published: 21 October 2020 Abstract: Background: Re-vaccination against canine adenovirus (CAV) is performed in 3-year-intervals but its necessity is unknown. The study determined anti-CAV antibodies within ≤ 28 days of re-vaccination and factors associated with the absence of antibodies and vaccination response. Methods: Ninety-seven healthy adult dogs (last vaccination 12 months) were re-vaccinated ≥ with a modified live CAV-2 vaccine. Anti-CAV antibodies were measured before vaccination (day 0), and after re-vaccination (day 7, 28) by virus neutralization. A 4-fold titer increase was defined ≥ as vaccination response. Fisher’s exact test and multivariate regression analysis were performed to determine factors associated with the absence of antibodies and vaccination response. Results: Totally, 87% of dogs (90/97; 95% CI: 85.61–96.70) had anti-CAV antibodies ( 10) before re-vaccination. -

Coronaviruses in Domestic Species (Updated February 18, 2020)

Coronaviruses in domestic species (Updated February 18, 2020) Note The WHO, FAO, and CDC indicate that pets and other domestic animals are not considered at risk for contacting COVID-19 or transmitting the virus that causes COVID-19 (also known as 2019-nCoV). The USDA has recently commented on the impact of COVID-19 on U.S. agricultural trade. Taxonomy • The Coronaviridae family gets its name, in part, because the virus surface is surrounded by a ring of projecting proteins that appear like a solar corona when viewed through an electron microscope. • The main Coronaviridae subfamily is subdivided into alpha- (formerly referred to as type 1 or phylogroup 1), beta- (formerly referred to as type 2 or phylogroup 2), delta-, and gammacoronavirus genera. • Coronaviruses have been isolated from dogs, cats, horses, cattle, swine, chickens, turkeys, and humans with clinical signs of disease. Most of these diseases are gastrointestinal or respiratory, but encephalomyelitis has been reported as occurring in pigs. A brief summary of these diseases by species can be found below the table. Coronaviruses recognized in domestic animals USDA Organ licensed Host Genus Virus - Disease system vaccine Dog Alpha CCoV - Canine coronavirus Enteric Yes Cat Alpha FECV - Feline enteric coronavirus Enteric No FIPV-FIP Systemic Yes1 Horse Beta ECoV - Equine coronavirus Enteric No Cattle Beta BCoV - Calf diarrhea Enteric Yes Winter dysentery Enteric BRD Respiratory Swine Alpha PEDV - Porcine epidemic diarrhea virus Enteric TGEV - Transmissible gastroenteritis virus Enteric Yes PRCV - Porcine respiratory coronavirus Respiratory Beta PHEV - Porcine hemagglutinating encephalomyelitis virus Delta PorCoV - Porcine coronavirus Enteric Chickens Gamma IBV - Avian infectious bronchitis virus Respiratory Yes Turkeys Gamma Bluecomb - Turkey coronavirus Enteric ______ No_____ 1 Not recommended by the AAFP for administration. -

2017 AAHA Canine Vaccination Guidelines* Richard B

2017 AAHA Canine Vaccination Guidelines* Richard B. Ford, DVM, MS, DACVIM, DACVPM (Hon)†, Laurie J. Larson, DVM, Kent D. McClure, DVM, JD, Ronald D. Schultz, PhD, DACVM (Hon), Link V. Welborn, DVM, DABVP‡ AFFILIATIONS North Carolina State University, College of Veterinary Medicine, Raleigh, North Carolina (R.B.F.); Department of Pathobiological Sciences, University of Wisconsin-Madison School of Veterinary Medicine, Madison, Wisconsin (L.J.L.); General Counsel, Animal Health Institute, Washington, DC (K.D.M.); Department of Pathobiological Sciences, University of Wisconsin-Madison School of Veterinary Medicine, Madison, Wisconsin (R.D.S.); Tampa Bay Animal Hospitals, Tampa, Florida (L.V.W.). CONTRIBUTING REVIEWERS Catherine M. Brown, DVM, MSc, MPH (Massachusetts Department of Public Health); Anthony E. Cascino, Jr. Attorney at Law (Cascino & Assoc, P.C.; Chicago, Illinois); Leah A. Cohn, DVM, PhD, DACVIM (University of Missouri); Cynda Crawford, DVM, PhD (Maddie’s Shelter Program, University of Florida); Michael J. Day, BSc, BVMS (Hons), PhD, DECVP (University of Bristol, United Kingdom); Cynthia Delany, DVM (University of California, Davis); Brian DiGangi, DVM, DABVP (University of Florida); Kelli Ferris, DVM (North Carolina State University); Laurel Gershwin, DVM, PhD, DACVM (University of California, Davis); Douglas C. Jack, Solicitor (Borden Ladner Gervais LLP, Toronto, Canada); Linda Janowitz, DVM (Peninsula Humane Society); Lila Miller, DVM (American Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals, New York City); Susan Moore, MS, PhD, director of KSVDL Rabies Laboratory (Kansas State University); Kris Otteman, DVM (Oregon Humane Society); Apryl Steele, DVM (Chief Operating Officer, Dumb Friends League); Brenda Stevens, DVM (North Carolina State University); Amy Stone, DVM, PhD (University of Florida); Jane Sykes, BVSc, PhD, DACVIM (University of California, Davis). -

Subscribe Rs

NEW DELHI TIMES R.N.I. No 53449/91 DL-SW-1/4124/20-22 (Monday/Tuesday same week) (Published Every Monday) New Delhi Page 24 Rs. 7.00 29 March - 4 April 2021 Vol - 31 No. 9 Email : [email protected] Founder : Dr. Govind Narain Srivastava ISSN -2349-1221 National Population Register: Don’t Envy; Compete! Need of the Hour In dark honest and agonizing moments, we recognize with considerable National Population Registration (NPR) is regret and pain all the things that are missing from our lives. Of course, an important document that was scheduled there are a considerable number of things missing from our lives, to be updated along with the House listing like the career we wanted, or we may have made some catastrophic phase of Census 2021 during April to mistakes that have profoundly affected our lives, or our appearance September 2020 in all the States/UTs may be dissatisfying or in decline and so on. except Assam. We face humiliation in the face of desire we cannot have. The aim was to look into growth of We must admit that there are numerous unfulfilled desires population over the decade, to identify within us that eventually but undoubtedly cause us to Indian citizen and state of their livelihood, to envy. We have in life a lot of things that we desire, from a provide better facilities as Indian... companionship to materialistic desires but we... By Dr. Ankit Srivastava Page 3 By Dr. Pramila Srivastava Page 24 By NDT Special Bureau Page 2 The death of a true feminist in the Bangladesh Golden Jubilee Celebration of Indus Water Treaty is most Islamic world Independence with PM Modi generous, but Pakistan cribs Nawal Saadawi, a renowned Arab feminist from Egypt, a On March 26, 1971, East Pakistan was liberated from Way back in 1960, a decade into independence, India psychiatrist and novelist, whose writings triggered anger the clutches of Military Rule of West Pakistan. -

CANINE VACCINATION GUIDELINES Classification of a Vaccine

PROCEEDINGS BOOK I 551 CANINE VACCINATION GUIDELINES classification of a vaccine. For example, in the UK, Leptospira vaccine is considered core for the dog Professor Michael J. Day and attempts are now being made to provide data BSc BVMS(Hons) PhD DSc DiplECVP FASM that define disease prevalence [3]. FRCPath FRCVS School of Veterinary Sciences, University of Bristol, CORE VACCINATION United Kingdom The vaccination of puppies is determined by the [email protected] transfer of maternally-derived antibody (MDA) from the bitch in colostrum. This antibody is There are two sets of canine vaccination guidelines crucial for protection of the pup during early available: those produced by the American Animal life, but simultaneously blocks the endogenous Hospital Association [1] and those from the WSAVA immune response of the puppy to vaccination. Vaccination Guidelines Group (VGG) [2]. The Canine immunoglobulin has a half life of around fundamental principle of both sets of guidelines, as 11 days and there is progressive decline in MDA encapsulated by the VGG, is that ‘we should aim concentrations in pups over the first weeks of life. to vaccinate every animal with core vaccines and The ‘window of susceptibility’ occurs when there is to vaccinate each individual less frequently by only no longer sufficient maternal antibody to provide giving non-core vaccines that are necessary for that full protection from infectious disease, but where animal’. This presentation aims to explain how this sufficient antibody remains to block the ability statement relates to canine vaccination. of the pup to make its own immune response to modified live virus (MLV) vaccine. -

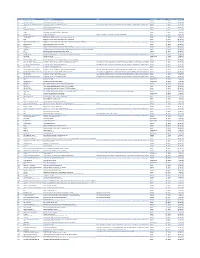

Cvx List.Pdf

CVX Code CVX Short Description Full Vaccine Name Note VaccineStatus internalID nonvaccine update_date 54 adenovirus, type 4 adenovirus vaccine, type 4, live, oral Inactive 1 False 28-May-10 55 adenovirus, type 7 adenovirus vaccine, type 7, live, oral Inactive 2 False 28-May-10 82 adenovirus, unspecified formulation adenovirus vaccine, unspecified formulation This CVX code allows reporting of a vaccination when formulation is unknown (for example, when reInactive 3 False 30-Sep-10 24 anthrax anthrax vaccine Active 4 False 11-Jun-19 19 BCG Bacillus Calmette-Guerin vaccine Active 5 False 28-May-10 27 botulinum antitoxin botulinum antitoxin Active 6 True 4-Sep-20 26 cholera, unspecified formulation cholera vaccine, unspecified formulation Inactive 7 False 17-Jun-16 29 CMVIG cytomegalovirus immune globulin, intravenous Active 8 True 4-Sep-20 56 dengue fever dengue fever vaccine Applies to dengue tetravalent product (e.g. DENGVAXIA) Active 9 False 24-Sep-19 12 diphtheria antitoxin diphtheria antitoxin Active 10 True 4-Sep-20 28 DT (pediatric) diphtheria and tetanus toxoids, adsorbed for pediatric use Active 11 False 28-May-10 20 DTaP diphtheria, tetanus toxoids and acellular pertussis vaccine Active 12 False 28-May-10 106 DTaP, 5 pertussis antigens diphtheria, tetanus toxoids and acellular pertussis vaccine, 5 pertussis antigens Active 13 False 28-May-10 107 DTaP, unspecified formulation diphtheria, tetanus toxoids and acellular pertussis vaccine, unspecified formulation This CVX code allows reporting of a vaccination when formulation is unknown -

Rabies Virus Antibodies from Oral Vaccination As a Correlate of Protection Against Lethal Infection in Wildlife

Tropical Medicine and Infectious Disease Article Rabies Virus Antibodies from Oral Vaccination as a Correlate of Protection against Lethal Infection in Wildlife Susan M. Moore 1,* ID , Amy Gilbert 2, Ad Vos 3, Conrad M. Freuling 4 ID , Christine Ellis 2, Jeannette Kliemt 4 and Thomas Müller 4 ID 1 Kansas State University, Veterinary Diagnostic Laboratory, Rabies Laboratory, Manhattan, KS 66502, USA 2 National Wildlife Research Center, US Department of Agriculture, Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service, Wildlife Services, Fort Collins, CO 80521, USA; [email protected] (A.G.); [email protected] (C.E.) 3 IDT Biologika GmbH, 06861 Dessau-Rosslau, Germany; [email protected] 4 Friedrich-Loeffler-Institut, Federal Research Institute for Animal Health, Institute of Molecular Virology and Cell Biology, 17493 Greifswald-Insel Riems, Germany; Conrad.Freuling@fli.de (C.M.F.); Jeannette.Kliemt@fli.de (J.K.); Thomas.Mueller@fli.de (T.M.) * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +1-785-532-4472 Received: 2 June 2017; Accepted: 8 July 2017; Published: 21 July 2017 Abstract: Both cell-mediated and humoral immune effectors are important in combating rabies infection, although the humoral response receives greater attention regarding rabies prevention. The principle of preventive vaccination has been adopted for strategies of oral rabies vaccination (ORV) of wildlife reservoir populations for decades to control circulation of rabies virus in free-ranging hosts. There remains much debate about the levels of rabies antibodies (and the assays to measure them) that confer resistance to rabies virus. In this paper, data from published literature and our own unpublished animal studies on the induction of rabies binding and neutralizing antibodies following oral immunization of animals with live attenuated or recombinant rabies vaccines, are examined as correlates of protection against lethal rabies infection in captive challenge settings. -

Canine Nomograph Evaluation Improves Puppy Immunization

Canine nomograph evaluation improves puppy immunization Laurie Larson, Bliss Thiel, Vanessa Santana, Ronald Schultz Companion Animal Vaccine and Immuno Diagnostics Service Laboratory Department of Pathobiological Sciences University of Wisconsin School of Veterinary Medicine Madison, WI Abstract Immunization failure in puppies by modified live vaccines for canine distemper virus and canine parvovirus can occur due to interference from maternally derived antibody. Quantitative measurement of specific antibody (via half-life degradation analysis; nomograph) is available to determine passive transfer from dam. Nomograph enables vaccination timing and followup titer testing tailored for each litter. Objective was to evaluate effectiveness of this approach and use of a nomograph. Puppies (506 puppies < 1 year) that had nomograph completed for their dam were not different in protection rate compared to vaccinated adults and were proven immune at 15.9 weeks. A cohort of similar puppies at 21.6 weeks that did not have nomograph completed for their dam was more likely to have not responded to vaccination. Keywords: Canine, nomograph, titer, vaccination, distemper, parvovirus Introduction Maternally derived antibody (MDA) interference with vaccination is considered as main cause for “failure to immunize” in puppies < 6 months old.1-4 Determining breeding dam antibody titers and applying half life degradation analysis to litter (nomograph) improved timing for canine distemper virus (CDV) vaccination.5 This concept was not widely adopted, since very few diagnostic laboratories offered canine vaccinal antibody testing. Beginning in late 1990’s, an alarming increase in adverse reactions to vaccines, most notably feline vaccine associated sarcoma,6 triggered veterinary profession to reevaluate annual vaccinations, standard practice at that time, for pet dogs and cats.