Research to Guide Strategic Communication for Protected Area Management

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Review of Natural Values Within the 2013 Extension to the Tasmanian Wilderness World Heritage Area

A review of natural values within the 2013 extension to the Tasmanian Wilderness World Heritage Area Nature Conservation Report 2017/6 Department of Primary Industries, Parks, Water and Environment Hobart A review of natural values within the 2013 extension to the Tasmanian Wilderness World Heritage Area Jayne Balmer, Jason Bradbury, Karen Richards, Tim Rudman, Micah Visoiu, Shannon Troy and Naomi Lawrence. Department of Primary Industries, Parks, Water and Environment Nature Conservation Report 2017/6, September 2017 This report was prepared under the direction of the Department of Primary Industries, Parks, Water and Environment (World Heritage Program). Australian Government funds were contributed to the project through the World Heritage Area program. The views and opinions expressed in this report are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of the Tasmanian or Australian Governments. ISSN 1441-0680 Copyright 2017 Crown in right of State of Tasmania Apart from fair dealing for the purposes of private study, research, criticism or review, as permitted under the Copyright act, no part may be reproduced by any means without permission from the Department of Primary Industries, Parks, Water and Environment. Published by Natural Values Conservation Branch Department of Primary Industries, Parks, Water and Environment GPO Box 44 Hobart, Tasmania, 7001 Front Cover Photograph of Eucalyptus regnans tall forest in the Styx Valley: Rob Blakers Cite as: Balmer, J., Bradbury, J., Richards, K., Rudman, T., Visoiu, M., Troy, S. and Lawrence, N. 2017. A review of natural values within the 2013 extension to the Tasmanian Wilderness World Heritage Area. Nature Conservation Report 2017/6, Department of Primary Industries, Parks, Water and Environment, Hobart. -

60 Great Short Walks 60 60 Great Short Walks Offers the Best of Tasmania’S Walking Opportunities

%JTDPWFS5BTNBOJB 60 Great Short Walks 60 60 Great Short Walks offers the best of Tasmania’s walking opportunities. Whether you want a gentle stroll or a physical challenge; a seaside ramble or a mountain vista; a long day’s outing or a short wander, 60 Great Short Walks has got plenty for you. The walks are located throughout Tasmania. They can generally be accessed from major roads and include a range of environments. Happy walking! 60 Great Short Walks around Tasmania including: alpine places waterfalls Aboriginal culture mountains forests glacial lakes Above then clockwise: beaches Alpine tarn, Cradle Mountain-Lake tall trees St Clair National Park seascapes Mt Field National Park Cradle Mountain, history Cradle Mountain-Lake St Clair National Park islands Lake Dove, Cradle Mountain-Lake St Clair wildlife National Park and much more. Wineglass Bay, Freycinet National Park 45 47 46 33 34 35 38 48 Devonport 39 50 49 36 41 Launceston 40 51 37 29 30 28 32 31 42 44 43 27 52 21 20 53 26 24 57 Strahan 19 18 54 55 23 22 56 25 15 14 58 17 16 Hobart 60 59 1 2 Please use road 3 13 directions in this 4 5 booklet in conjunction 12 11 6 with the alpha-numerical 10 7 system used on 8 Tasmanian road signs and road maps. 9 45 47 46 33 34 35 38 48 Devonport 39 50 49 36 41 Launceston 40 51 37 29 30 28 32 31 42 44 43 27 52 21 20 53 26 24 57 Strahan 19 18 54 55 23 22 56 25 15 14 58 17 16 Hobart 60 59 1 2 3 13 4 5 12 11 6 10 7 8 9 Hobart and Surrounds Walk Organ Pipes, Mt Wellington Hobart 1 Coal Mines Historic Site Tasman Peninsula 2 Waterfall Bay Tasman -

3966 Tour Op 4Col

The Tasmanian Advantage natural and cultural features of Tasmania a resource manual aimed at developing knowledge and interpretive skills specific to Tasmania Contents 1 INTRODUCTION The aim of the manual Notesheets & how to use them Interpretation tips & useful references Minimal impact tourism 2 TASMANIA IN BRIEF Location Size Climate Population National parks Tasmania’s Wilderness World Heritage Area (WHA) Marine reserves Regional Forest Agreement (RFA) 4 INTERPRETATION AND TIPS Background What is interpretation? What is the aim of your operation? Principles of interpretation Planning to interpret Conducting your tour Research your content Manage the potential risks Evaluate your tour Commercial operators information 5 NATURAL ADVANTAGE Antarctic connection Geodiversity Marine environment Plant communities Threatened fauna species Mammals Birds Reptiles Freshwater fishes Invertebrates Fire Threats 6 HERITAGE Tasmanian Aboriginal heritage European history Convicts Whaling Pining Mining Coastal fishing Inland fishing History of the parks service History of forestry History of hydro electric power Gordon below Franklin dam controversy 6 WHAT AND WHERE: EAST & NORTHEAST National parks Reserved areas Great short walks Tasmanian trail Snippets of history What’s in a name? 7 WHAT AND WHERE: SOUTH & CENTRAL PLATEAU 8 WHAT AND WHERE: WEST & NORTHWEST 9 REFERENCES Useful references List of notesheets 10 NOTESHEETS: FAUNA Wildlife, Living with wildlife, Caring for nature, Threatened species, Threats 11 NOTESHEETS: PARKS & PLACES Parks & places, -

5 Days out West Camping and 5 DAYS of CAMPING and DAYWALKS in the TASMANIAN WILDERNESS Walking Tour

FACTSHEET DURATION: 5 days 4 nights 5 Days Out West Camping and 5 DAYS OF CAMPING AND DAYWALKS IN THE TASMANIAN WILDERNESS Walking Tour KEY TO INCLUDED MEALS BELOW: (B): Breakfast (L): Lunch (D): Dinner Launceston to Hobart. Want to discover the remote and wild Tasmanian West Coast? Then this is the tour for you. Over 5 Days we explore the iconic “must sees” as well as some great local secrets. Camping out and watching the wildlife. This tour starts in Launceston and finishes in Hobart. The ideal tour to experience Tasmania’s wild and remote west coast. We aim to stay away from the crowds, from camping in the bush to sleeping beside the ocean under the stars. Enjoy bushwalks through Cradle Mountain, the Tarkine and Lake St Clair. Cross the west coast’s Pieman River at Corinna, a remote settlement and camp beside the Southern Ocean. Marvel at Tasmania’s tallest waterfall, Montezuma Falls and drive through Franklin-Gordon Wild Rivers National Park. Visit some of Australia’s tallest trees in the Styx Valley. Each day we participate in bush walks from 1- 5 hours and travel by four- wheel-drive troop carriers which are ideal to access remote areas. Each night we experience bush camping and delicious meals with campfire cooking. When we camp we use tents or you can sleep under the stars and we supply cosy swags. We see and appreciate Tasmania’s unique wildlife in the wild. FACTSHEET 5 DAYS OUT WEST TASAFARI (cont) Day 1: Cradle Mountain (L, D) Depart Launceston at 7.30am — pick-ups from your accommodation. -

Mild, Wild & Untamed Tasmania

Mild, Wild & Untamed Tasmania 10 Days of Tasmanian Nature Experiences The Experience - 10 days & 10 nights This tour features a collection of Tasmanian’s premium nature based products, covering a large area of the State and experiencing a diversity of landscapes, wildlife and lifestyles. Day 1 -Trowunna Wildlife to Strahan Today we travel to the beautiful Meander Valley for a private tour at the Trowunna Wildlife Park. Cuddle a wombat, meet the Tasmanian devil, spotted tailed quoll and other fur and feathered residents. After lunch we continue the journey to Strahan Overnight: Strahan - dinner inclusive Day 2 - Strahan - Gordon River Cruise Cruise the Gordon River with World Heritage Cruises. A full day, see Hell’s Gates, Salmon farms, guided Sarah Island stop-over, Gordon River heritage landing board walk and Huon Pine Sawmill with a buffet lunch. Before dinner, sit in on the interactive play, The Ship That Never Was Overnight: Strahan Village - dinner inclusive Day 3 - Strahan to Cradle Mountain Departing Strahan our journey today takes us to Cradle Mountain. Cradle offers a range of walks of varied distances, amazing alpine flora and wombats grazing. Visit Waldheim Lodge to learn of the history and hardships involved in achieving National Park status. Overnight: 2 nights at Cradle Mountain Hotel - dinner inclusive Day 4 - Cradle to Launceston Departing Cradle Mountain we travel to the beautiful Tamar Valley to visit the platypus and echidna at Platypus House. Tamar Valley vineyards are also on offer before finishing the day in Scottsdale Overnight: Beulah Heritage Accommodation - dinner inclusive Day 5 - Ben Lomond & Quoll Patrol Depart Scottsdale to visit the majestic alpine peaks of Ben Lomond National Park - travel via the Roses Tier forests and Tombstone Creek Forest Reserve to the Tyne Valley for a camp fire dinner with the kangaroos and nocturnal wildlife tour. -

Lands of Tasmania" an E1tor Was Made in Each of These Averages, B

(No. 28.) 18 6 4. TASMANIA. L E G I S L A T I V E C O U N C 1 L. L A N D S OF T A S M A N I A. Laid on the Table by Mr. Whyte, and ordered by the Council to be printed, July 1, 1864. .. OF TAS1\1ANIA; COMPILED FROM THE OF~CIAL RECORDS OF THE SURVEY DEPARTMENT, BY ORDER OF THE HONORABLE THE COLONIAL TREASURER Made up to the 31st December, 1862. «ar;mani,t: JAMES BARNARD, GOVERNMENT PRINTER, HOBART TOWN. \ 18 6 4. T A B LE OF C O N T E N T S. PAGE PREFACE •••••.••••••••••••••••••• 3 Area of Tasmania, with alienated and unalienated Lands ...........••... , • . 17 Population of Tasmania •. , ..... , . • . • • . • • . • . • . • . ib. Ditto of Towns .................•••.........•.......... _. 18 · Country Lands granted and sold since 1804 ..•• , •• , ..•....•....... , . • • • . 19 Town Lands sold ..••••......•.......••••...••• , . • . 20 'fown Lands sold for Cash under " The Waste Lands Act" . • • • • • • . 21 Deposits forfeited on ditto. • • • • • • . • . ... , . • • . • . • . 40 Town Lands sold on Credit .......... , ......••.. , , ......... , ..•.... , . , . 42 Agricultuml Lands sold for Cash, under 18th Sect. of '' The Waste Lands Act". 4'5 Ditto on Credit, ditto ...• .', . • . • . • • • • . • . • 46 Ditto for Cash, under 19th Sect. of" The Waste Lands Act" . 49 Ditto on Credit, ditto ....•••••.•....... , , ....... , ....• •... , . • • • • • . 51 Ditto for Cash at Public Auction .••••.............•••.••. , , • . 62 Deposits forfeited on ditto ...... , ........• , .......•.. , . • . 64 Agricultural Lands sold on Credit at Public Auction , •.•••••..•••••.• , . 65 Pastoral Lands sold for CashJ under 18th Sect. of" The ·waste Lands Act" .. , . 71 Ditto on Credit, ditto .•••...•....••..••..•..••............• , • . • • . ib. Ditto for Cash at Public Auction ....•.•.•.•...... , . • • . • . • • . • . 73 Deposits forfeited on ditto •.••••............•., • , • • . • • • . • • • . 74 Pastoral Lands sold on Credit at Public Auction...... -

Australia & NZ Magazine

HOLIDAY DERWENT VALLEY WITH ITS YESTERYEAR HAUNTS, MOUNTAINOUS PEAKS AND ARTY INSTALLATIONS, TASMANIA’S DERWENT VALLEY IS A JOURNEY OF INTRIGUE AND DISCOVERY WORDS: Marie Barbieri can’t quite decide if it’s eerie and haunted, or nostalgic and dreamy. It has a forlorn beauty about it, with a conical cowl on its dilapidated hexagonal tower. I stand and stare admiring it, imagining how atmospheric it would be as a film set. I yearn to learn of its past. Who built it? Who lived in it? Do ghosts reside inside? I“G’day!” bursts a voice behind the fence, from a young man wielding a shovel, having me near jump out of my skin. The chap laughs, amused by my juggling a camera, water bottle and banana—all of which now land on the ground. “Baaaah!” When a sheep comes bouncing towards us, I realise that this is no abandoned property. “What Main image: A picturesque a beautiful building,” I say. “Sure is,” he replies. view of the Derwent River Marie Barbieri Marie Images: Images: 24 Australia & NZ | October 2019 www.getmedownunder.com www.getmedownunder.com Australia & NZ | October 2019 25 HOLIDAY DERWENT VALLEY Humour also resides at Sheen Estate and Distillery “It was built in the late 1820s by Josiah Spode (of Above: Rodney in Pontville. Set in a historic heritage precinct, you Dunn at The Agrarian British tableware fame). Its kiln dried hops for beer Kitchen can sip on Poltergeist Gin (dubbed: the ‘true spirit’). It production until the 1960s. And we get a lot of people has earned multiple awards in the coveted San Francisco like you admiring it from the road.” World Spirits Competition. -

Freycinet & Cradle Mountain

FREYCINET & CRADLE MOUNTAIN Freycinet & Cradle Mountain Signature Self Drive 6 Days / 5 Nights Hobart to Launceston Departs Daily Priced at USD $1,476 per person Price is based on peak season rates. Contact us for low season pricing and specials. INTRODUCTION Highlights: Hobart | Freycinet National Park | Cradle Mountain | Launceston Explore Tasmania’s rugged and wild heart with visits to its capital city, lush and abundant national parks and your choice of one of four day toursFeel utterly captivated by Freycinet’s pink granite cliffs and sparkling sea, then take a cruise in Wineglass Bay before traveling on to LauncestonCradle Mountain has been listed as one of Tasmania’s most picturesque nature parks, and the Tamar Valley is teeming with wine for you to try. Itinerary at a Glance DAY 1 Hobart Arrival DAY 2 Hobart | Freedom of Choice – 1 of 4 Excursions 1. Private Tasmania's Wilderness & Wildlife Tour 2. Private Mt Wellington and Huon Valley Food and Wine Tour 3. Tasmanian Seafood Seduction Cruise 4. Private Tasmania's History & Devils Tour DAY 3 Freycinet National Park | Wineglass Bay & Freycinet Peninsula Cruise DAY 4 Launceston | Epicenter for Food, Wine, Culture & Nature DAY 5 Cradle Mountain | Ancient Rainforests & Alpine Peaks Trails DAY 6 Launceston Departure Start planning your tailor-made vacation in Australia, Fiji and New Zealand by contacting our South Pacific specialists Call 1 855 465 1030 (Monday - Saturday 9am - 5pm Pacific time) Email [email protected] Web southpacificbydesign.com Suite 1200, 675 West Hastings Street, Vancouver, BC, V6B 1N2, Canada 2019/12/17 Page 1 of 4 FREYCINET & CRADLE MOUNTAIN MAP DETAILED ITINERARY Day 1 Arrive Hobart Welcome to Tasmania! Upon arrival in Hobart your driver will pick you up and transfer you to your accommodation. -

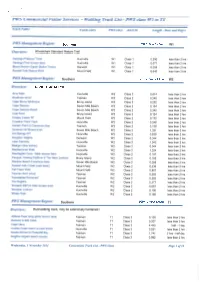

Walking Track List - PWS Class Wl to T4

PWS Commercial Visitor Services - Walking Track List - PWS class Wl to T4 Track Name FieldCentre PWS class AS2156 Length - Kms and Days PWS Management Region: Southern PWS Track Class: VV1 Overview: Wheelchair Standard Nature Trail Hastings Platypus Track Huonville W1 Class 1 0.290 less than 2 hrs Hastings Pool access track Huonville W1 Class 1 0.077 less than 2 hrs Mount Nelson Signal Station Tracks Derwent W1 Class 1 0.059 less than 2 hrs Russell Falls Nature Walk Mount Field W1 Class 1 0.649 less than 2 hrs PWS Management Region: Southern PWS Track Class: W2 Overview: Standard Nature Trail Arve Falls Huonville W2 Class 2 0.614 less than 2 hrs Blowhole circuit Tasman W2 Class 2 0.248 less than 2 hrs Cape Bruny lighthouse Bruny Island W2 Class 2 0.252 less than 2 hrs Cape Deslacs Seven Mile Beach W2 Class 2 0.154 less than 2 hrs Cape Deslacs Beach Seven Mile Beach W2 Class 2 0.345 less than 2 hrs Coal Point Bruny Island W2 Class 2 0.124 less than 2 hrs Creepy Crawly NT Mount Field W2 Class 2 0.175 less than 2 hrs Crowther Point Track Huonville W2 Class 2 0.248 less than 2 hrs Garden Point to Carnarvon Bay Tasman W2 Class 2 3.138 less than 2 hrs Gordons Hill fitness track Seven Mile Beach W2 Class 2 1.331 less than 2 hrs Hot Springs NT Huonville W2 Class 2 0.839 less than 2 hrs Kingston Heights Derwent W2 Class 2 0.344 less than 2 hrs Lake Osbome Huonville W2 Class 2 1.042 less than 2 hrs Maingon Bay lookout Tasman W2 Class 2 0.044 less than 2 hrs Needwonnee Walk Huonville W2 Class 2 1.324 less than 2 hrs Newdegate Cave - Main access -

Australia EXTRAORDINARY OVERLAND EXPEDITIONS

Australia EXTRAORDINARY OVERLAND EXPEDITIONS PRE-RELEASE BROCHURE 2020 OUTBACKSPIRITTOURS.COM.AU Welcome to Outback Spirit Australia’s leading small group tour company Exploring the vast Australian Outback is for many people like an awakening. It delivers an enhanced sense and new perspective of this extraordinary country; it’s environment, culture, wildlife and history. Outback Spirit has been showcasing the Outback for 21 years. From modest beginnings with a single 4WD bus, we’ve grown to become the number 1 choice for Australians seeking a small group outback adventure. Over the past year nearly 7000 people travelled with us into the outback, half of which were repeat clients setting off on another adventure. Getting off the beaten track without sacrificing comfort or professionalism has been a hallmark of our brand since the very beginning. Our fleet of luxury 4WD Mercedes Benz coaches provide an unrivalled level of comfort and safety, whilst our passionate and knowledgeable guides make every trip an enlightening and memorable experience. Delivering above and beyond expectations is what Outback Spirit is known for. Join us for an adventure in 2020, and you’ll see why. Andre & Courtney Ellis Brothers / Founders / Owners 3 Why Choose Outback Spirit? Award winning tour company Number 1 in the outback. The company that more Australians choose for small group outback touring Australia’s largest range of outback expeditions All Mercedes Benz fleet, guaranteeing your comfort and safety Passionate & experienced tour leaders 10 year Experience -

Tasmania - Tarkine to Tasman Peninsula 06–20 March 2020 (14 Nights)

Tasmania - Tarkine to Tasman Peninsula 06–20 March 2020 (14 nights) Highlights • Walk through eucalypt and tree fern forests to Liffey Falls • Experience the fabled Walls of Jerusalem National Park • Marvel subterranean caves at Mole Creek Karst National Park • Take in the splendour of The Nut in Stanley • Stay in secluded Tarkine wilderness cottages • Explore ancient forests at Mt Donaldson & Mt Rufus • Experience Cradle Mountain - Lake St Claire National Park • Walk to Russell Falls in Mt Fields National Park • Hike the dramatic cliffs of Cape Raoul in Tasman National Park • Take time to contemplate the Port Arthur Historic Site • Cruise the Western Wilderness & Tasman Peninsula Meeting in Launceston, we travel to our first walk at Liffey Falls surrounded by cool temperate rainforest. Staying three nights in the Mole Creek area, we explore the subterranean world of Mole Creek Karst National Park. After walks in the Jurassic landscape of Walls of Jerusalem National Park, we have the chance to learn more about the iconic Tasmanian devil. We turn to the north west coast, with views of the Bass Strait all the way to The Nut in Stanley. Along the way we visit the iconic Sheffield murals and Rocky Cape National Park. Taking in the remote town of Arthur River, we descend into the ancient landscape of the western wilderness where we stay in secluded rainforest cottages. To experience the many moods of the Tarkine, we cruise the Pieman River, enjoy walks in Australia's largest temperate myrtle-beech pristine rainforest and have the option to kayak secluded waterways. We walk through prehistoric Gondwana landscapes of button grass plains and wildflowers to the summit of Mt Donaldson. -

Classic West 4

4 Day West Coast Camp - Hobart to Launceston Want to discover the remote and wild Tasmanian West Coast? then this is the tour for you. Over 4 Days we explore the iconic must sees as well as some great local secrets. Camping out and watching the wildlife We are more than just a bus tour - We are different because • We take time to walk in the areas we visit, not just take a picture and keep driving • The guide will be with you on most walks to show you the wonders we find along the way • We camp in quality hiking tents in great locations • We see much more wildlife when you camp away from the towns • Small personal groups. Maximum of 10 people per tour • Family friendly and private tours also available • Discounts available for multiple tours booked at same time This tour starts in Hobart and finishes in Launceston, 4 Days and 3 Nights Camping and Walking Tour The ideal tour to experience Tasmania’s wild and remote west coast. We aim to stay away from the crowds, from camping in the bush to sleeping beside the ocean under the stars. Enjoy bush walks through Mt Field and see its spectacular waterfalls. Search for platypus at Lake St Clair. Drive through Franklin-Gordon Wild Rivers National Park. Ramble on some rugged and remote west coast beaches. Marvel at one of Tasmania’s tallest waterfalls. Immerse your self in the beauty of Cradle Mountain Each day we participate in bush walks from 1- 5 hours and travel by four-wheel-drives or mini .