Jersey & Guernsey Law Review

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Ceremony of Light • Fête De St Helier 2014 • 20,000 Flowers Beside the Sea Crossing Pegasus Bridge • Jersey Infertil

Photograph courtesy of Nelio from Camera Moment A Ceremony of Light • Fête de St Helier 2014 • 20,000 flowers beside the sea Crossing Pegasus Bridge • Jersey Infertility Support • Havre des Pas Seaside Festival View on St Helier – André Ferrari • Dates for your diary • St Helier Gazette Delivered by Jersey Post to 19,000 homes and businesses every month. Designed and produced by MailMate Publishing Jersey in partnership with the Parish of St Helier. Clear investment. Pure energy. DIRECT DEBIT THE SMARTER WAY TO PAY YOUR BILL You are billed as normal for the electrcity you have used. Your bank transfers the full payment 18 days after you have recieved and checked your statement. No fuss. No missed payment dates. CHEQU A E E K B I U L T - B T V I E T A B T E R E D I R A B T L C E E D I R The cost of your annual consumption Paid direct by your bank No fuss. No missed divided into 12 equal monthly payments. on a date to suit you. payment dates. FIXED DIRECT DEBIT - SPREADS THE COST FOR PEACE OF MIND Save £12 a year off your bill when you + pay by Direct Debit and switch to ebills Tel 505460 The symbol that offers our customers every protection. www.jec.co.uk/directdebit elcome to the September edition of the Town Crier. WSummer in St Helier is festival season and we have lots Contents to report on with some stunning photographs of the range of events Parish matters – A Ceremony of Light 4 that have taken place in our Parish. -

The Jersey Heritage Answersheet

THE JERSEY HERITAGE Monuments Quiz ANSWERSHEET 1 Seymour Tower, Grouville Seymour Tower was built in 1782, 1¼ miles offshore in the south-east corner of the Island. Jersey’s huge tidal range means that the tower occupies the far point which dries out at low tide and was therefore a possible landing place for invading troops. The tower is defended by musket loopholes in the walls and a gun battery at its base. It could also provide early warning of any impending attack to sentries posted along the shore. 2 Faldouet Dolmen, St Martin This megalithic monument is also known as La Pouquelaye de Faldouët - pouquelaye meaning ‘fairy stones’ in Jersey. It is a passage grave built in the middle Neolithic period, around 4000 BC, the main stones transported here from a variety of places up to three miles away. Human remains were found here along with finds such as pottery vessels and polished stone axes. 3 Cold War Bunker, St Helier A German World War II bunker adapted for use during the Cold War as Jersey’s Civil Emergency Centre and Nuclear Monitoring Station. The building includes a large operations room and BBC studio. 4 Statue of King George V in Howard Davis Park Bronze statue of King George V wearing the robes of the Sovereign of the Garter. Watchtower, La Coupe Point, St Martin 5 On the highest point of the headland is a small watchtower built in the early 19th century and used by the Royal Navy as a lookout post during the Napoleonic wars. It is sturdily constructed of mixed stone rubble with a circular plan and domed top in brick. -

Review of Birds in the Channel Islands, 1951-80 Roger Long

Review of birds in the Channel Islands, 1951-80 Roger Long ecords and observations on the flora and fauna in the Channel Islands Rare treated with confusing arbitrariness by British naturalists in the various branches of natural history. Botanists include the islands as part of the British Isles, mammalogists do not, and several subdivisions of entomo• logists adopt differing treatments. The BOU lists and records have always excluded the Channel Islands, but The Atlas of Breeding Birds in Britain and Ireland (1976) included them, as do all the other distribution mapping schemes currently being prepared by the Biological Records Centre at Monks Wood Experimental Station, Huntingdon. The most notable occurrences of rarities have been published in British Birds, and this review has been compiled so that the other, less spectacular—but possibly more significant—observations are available as a complement to the British and Irish records. The late Roderick Dobson, an English naturalist resident in Jersey between 1935 and 1948 and from 1958 to his death in 1979, was the author of the invaluable Birds of the Channel Islands (1952). In this, he brought together the results of his meticulous fieldwork in all the islands, and his critical interpretation of every record—published or private—that he was able to unearth, fortunately just before the turmoil of the years of German Occupation (1940-45) dispersed much of the material, perhaps for ever. I concern myself here chiefly with the changes recorded during the approxi• mately 30 years since Dobson's record closed. Species considered to have shown little change in status over those years are not listed. -

Draft Constitution of the States and Public Elections (Jersey) Law 202

STATES OF JERSEY DRAFT CONSTITUTION OF THE STATES AND PUBLIC ELECTIONS (JERSEY) LAW 202- Lodged au Greffe on 8th March 2021 by the Privileges and Procedures Committee Earliest date for debate: 20th April 2021 STATES GREFFE 2021 P.17/2021 DRAFT CONSTITUTION OF THE STATES AND PUBLIC ELECTIONS (JERSEY) LAW 202- European Convention on Human Rights In accordance with the provisions of Article 16 of the Human Rights (Jersey) Law 2000, the Chair of the Privileges and Procedures Committee has made the following statement – In the view of the Chair of the Privileges and Procedures Committee, the provisions of the Draft Constitution of the States and Public Elections (Jersey) Law 202- are compatible with the Convention Rights. Signed: Deputy C.S. Alves of St. Helier Chair, Privileges and Procedures Committee Dated: 8th March 2021 ◊ P.17/2021 Page - 3 Draft Constitution of the States and Public Elections (Jersey) Law 202- Report REPORT In December 2020, the Assembly adopted P.139/2020 “Composition and Election of the States: proposed changes” and, in so doing, agreed proposals which will allow progress to finally be made in the delivery of a fairer, better, simpler, more inviting elections for candidate and voter alike. These legislative changes implement paragraph (a) of P.139/2020, namely to establish an Assembly of 49 Members, 37 elected from 9 new districts of comparable population size, plus the 12 Parish Connétables. The Privileges and Procedures Committee (“PPC”) has resolved to bring this to the Assembly in 2 tranches. Drafting and consultation is ongoing to make all of the necessary changes to the various pieces of legislation which underpin the election system stemming from paragraphs (b), (c) and (d) of P.139/2020, but the revisions to the constitution contained within this proposition are fundamental to those other legislative changes which will be debated in the next few months. -

Electricity (Jersey) Law 1937

1 Jersey Law 31/1937 [ELECTRICITY (JERSEY) LAW, 1937.]1 ____________ LOI accordant certains Pouvoirs, Droits, Privilèges et Obligations à la Société dite: “The Jersey Electricity Company Limited,” confirmée par Ordre de Sa Majesté en Conseil, en date du 22 OCTOBRE 1937. ____________ (Entériné le 27 novembre 1937). ____________ AUX ETATS DE L’ILE DE JERSEY. ____________ L’An 1937, le 6 avril. ____________ CONSIDERANT que par Actes des Etats en date du 8 juillet 1936 1° le Greffier des Etats fut autorisé à exercer définitivement la faculté d’acquisition de l’entier du capital ordinaire de la Société “Jersey Electricity Company Limited”, enregistrée en vertu de certain Acte de la Cour Royale, en date du 5e jour d’avril mil neuf cent vingt-quatre, en conformité des Lois sur les Sociétés à Responsabilité Limitée, passées par les Etats et confirmées par Sa Très Excellente Majesté en Conseil de 1861 à 1922;2 2° il fut décidé que les trente-cinq mille actions d’une livre Sterling, chacune, formant l’entier du dit capital ordinaire de ladite Société “Jersey Electricity Company Limited” seraient, lors de leur transfert aux Etats, enregistrées et tenues aux noms de Monsr. Herbert Frank Ereaut, 1 Title substituted by the Electricity (Amendment) (Jersey) Law, 1954 (Volume 1954–1956, page 189). 2 Tomes I–III, page 232. 1937–1938, 263–307. 2 Jersey Law 31/1937 [Electricity (Jersey) Law, 1937] Trésorier des Etats, et Hedley Le Riche Edwards, Ecuier, Greffier des Etats, pour et au nom des Etats de cette Ile; Considérant que ladite Société est établie dans l’Ile depuis l’année 1925 et que depuis cette date elle fournit la force électrique à une partie de l’Ile, laquelle partie augmente de plus en plus; Considérant que la fourniture de force électrique est une entreprise d’utilité publique, et qu’il est avantageux et désirable que ladite force électrique soit à la disposition des habitants de l’Ile entière; Considérant que les pouvoirs droits, privilèges et obligations de ladite Société ne sont pas établis ou gouvernés par autorité statutaire. -

48 St Saviour Q3 2020.Pdf

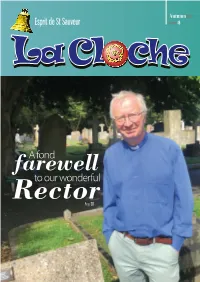

Autumn2020 Esprit de St Sauveur Edition 48 farewellA fond Rectorto our wonderful Page 30 C M Y CM MY CY CMY K Autumn 2020 St Saviour Parish Magazine p3 From the Editor Featured Back on Track! articles La Cloche is back on track and we have a full magazine. There are some poems by local From the Constable poets to celebrate Liberation and some stories from St Saviour residents who were in Jersey when the Liberation forces arrived on that memorable day, 9th May 1945. It is always enlightening to read and hear of others’ stories from the Occupation and Liberation p4 of Jersey during the 1940s. Life was so very different then, from now, and it is difficult for us to imagine what life was really like for the children and adults living at that time. Giles Bois has submitted a most interesting article when St Saviour had to build a guardhouse on the south coast. The Parish was asked to help Grouville with patrolling Liberation Stories the coast looking for marauders and in 1690 both parishes were ordered to build a guardhouse at La Rocque. This article is a very good read and the historians among you will want to rush off to look for our Guardhouse! Photographs accompany the article to p11 illustrate the building in the early years and then later development. St Saviour Battle of Flowers Association is managing to keep itself alive with a picnic in St Paul’s Football Club playing field. They are also making their own paper flowers in different styles and designs; so please get in touch with the Association Secretary to help with Forever St Saviour making flowers for next year’s Battle. -

Jersey's Spiritual Landscape

Unlock the Island with Jersey Heritage audio tours La Pouquelaye de Faldouët P 04 Built around 6,000 years ago, the dolmen at La Pouquelaye de Faldouët consists of a 5 metre long passage leading into an unusual double chamber. At the entrance you will notice the remains of two dry stone walls and a ring of upright stones that were constructed around the dolmen. Walk along the entrance passage and enter the spacious circular main Jersey’s maritime Jersey’s military chamber. It is unlikely that this was ever landscape landscape roofed because of its size and it is easy Immerse Download the FREE audio tour Immerse Download the FREE audio tour to imagine prehistoric people gathering yourself in from www.jerseyheritage.org yourself in from www.jerseyheritage.org the history the history here to worship and perform rituals. and stories and stories of Jersey of Jersey La Hougue Bie N 04 The 6,000-year-old burial site at Supported by Supported by La Hougue Bie is considered one of Tourism Development Fund Tourism Development Fund the largest and best preserved Neolithic passage graves in Europe. It stands under an impressive mound that is 12 metres high and 54 metres in diameter. The chapel of Notre Dame de la Clarté Jersey’s Maritime Landscape on the summit of the mound was Listen to fishy tales and delve into Jersey’s maritime built in the 12th century, possibly Jersey’s spiritual replacing an older wooden structure. past. Audio tour and map In the 1990s, the original entrance Jersey’s Military Landscape to the passage was exposed during landscape new excavations of the mound. -

(Jersey) Act 200

DRAFT MAIN ROADS (CLASSIFICATION) (No. 27) (JERSEY) ACT 200- _______________ Lodged au Greffe on 26th February 2002 by the Public Services Committee ______________________________ STATES OF JERSEY STATES GREFFE 150 2002 P.30 Price code: A REPORT Financial implications The annual costs of maintaining La Rue Le Masurier and L’Avenue et Dolmen du Pré des Lumières, which form part of the Gas Works gyratory system, are - (a) cleaning of roads, footpaths and open areas £3,310 (b) gulley cleaning and drain jetting £240 (c) road signs and markings (renewal/replacement £455 averaged over a five-year period) (d) bollards (maintenance and electricity) £26 (e) street lighting (maintenance and electricity) £1,600 (a), (b) and (c) will be absorbed in the tasks connected with direct labour within the Department’s existing operations but will lead to an overall reduction in the level of service provided. (d) and (e) are costs payable to the Jersey Electricity Company and are an additional burden on the budget which means that cost savings will have to be achieved elsewhere in the Committee’s cash limit. Manpower implications There are no additional manpower implications. Explanatory Note This Act classifies La Rue Le Masurier (in St. Helier and St. Saviour) and L’Avenue et Dolmen du Pré des Lumières (in St. Helier) as main roads (or grandes routes). The effect of this is to place those roads under the administration of the Public Services Committee. Loi (1914) sur la Voirie ____________ MAIN ROADS (CLASSIFICATION) (No. 27) (JERSEY) ACT 200- ____________ (Promulgated on the day of 200 ) ____________ STATES OF JERSEY ____________ The day of 200 ____________ [1] T HE STATES, in pursuance of Article 1 of the “Loi (1914) sur la Voirie”, as amended, have made the following Act - 1. -

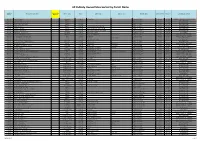

All Publicly Owned Sites Sorted by Parish Name

All Publicly Owned Sites Sorted by Parish Name Sorted by Proposed for Then Sorted by Site Name Site Use Class Tenure Address Line 2 Address Line 3 Vingtaine Name Address Parish Postcode Controlling Department Parish Disposal Grouville 2 La Croix Crescent Residential Freehold La Rue a Don Vingtaine des Marais Grouville JE3 9DA COMMUNITY & CONSTITUTIONAL AFFAIRS Grouville B22 Gorey Village Highway Freehold Vingtaine des Marais Grouville JE3 9EB INFRASTRUCTURE Grouville B37 La Hougue Bie - La Rocque Highway Freehold Vingtaine de la Rue Grouville JE3 9UR INFRASTRUCTURE Grouville B70 Rue a Don - Mont Gabard Highway Freehold Vingtaine des Marais Grouville JE3 6ET INFRASTRUCTURE Grouville B71 Rue des Pres Highway Freehold La Croix - Rue de la Ville es Renauds Vingtaine des Marais Grouville JE3 9DJ INFRASTRUCTURE Grouville C109 Rue de la Parade Highway Freehold La Croix Catelain - Princes Tower Road Vingtaine de Longueville Grouville JE3 9UP INFRASTRUCTURE Grouville C111 Rue du Puits Mahaut Highway Freehold Grande Route des Sablons - Rue du Pont Vingtaine de la Rocque Grouville JE3 9BU INFRASTRUCTURE Grouville Field G724 Le Pre de la Reine Agricultural Freehold La Route de Longueville Vingtaine de Longueville Grouville JE2 7SA ENVIRONMENT Grouville Fields G34 and G37 Queen`s Valley Agricultural Freehold La Route de la Hougue Bie Queen`s Valley Vingtaine des Marais Grouville JE3 9EW HEALTH & SOCIAL SERVICES Grouville Fort William Beach Kiosk Sites 1 & 2 Land Freehold La Rue a Don Vingtaine des Marais Grouville JE3 9DY JERSEY PROPERTY HOLDINGS -

St Clement'sschool

STCLEMMAIN-ed24-Summer-2016-3.qxp_Governance style ideas 03/06/2016 18:43 Page 1 St Clement Parish Magazine Twenty-fifth Edition•Summer2016 One man and his nag Above: Shakes Are Us has an army of loyal customers Left: Fresh fruit is always an alternative option STCLEMMAIN-ed24-Summer-2016-3.qxp_Governance style ideas 03/06/2016 18:43 Page 2 + www.designplus-architects.com designplusarchitects Top multi DESIGN AWARD winning practice JAB’15 Top multi TECHNICAL AWARD winning practice for Architectural Technical Excellence CIAT’15 architecture I interiors architecture I interior design new build I refurbishments I historic buildings bespoke homes I office blocks I extensions We offer all our client uncompromised and award winning SERVICE, DESIGN, TECHNICAL SOLUTIONS and successful project delivery, ON TIME AND ON BUDGET regardless of project size or complexity We offer an initial site visit, advice and appraisal consultation free of charge IF YOU ARE CONSIDERING A NEW BUILD, REFURBISMENT, EXTENSION OR ANY WORKS TO YOUR HOME, OFFICE OR BUSINESS WHATEVER THE SIZE, WE ARE HERE TO HELP tel : 01534 639773 mail : [email protected] STCLEMMAIN-ed24-Summer-2016-3.qxp_Governance style ideas 03/06/2016 18:43 Page 3 Summer2016 p3 Cover Picture: www.designplus-architects.com The Seigneur of Samarès, Vincent Welcome to L’Amarrage Obbard, taking Kimono – who answers to ‘Kim’ - for an early morning stroll in the manor grounds. + From theEditor In this edition: The clocks may have gone back at Easter, but it didn’t really feel as though spring had arrived. What with the P9 passing glance by Storm Katie which kept the ferries in Seaborne port and forced the cancellation of several outdoor paper-round events, it will probably be remembered as a ‘washout’. -

States of Jersey Transport and Technical Services

States of Jersey Transport and Technical Services Jersey DAP Needs Report July 2012 Prepared for: States of Jersey Transport and Technical Services Prepared by: Grontmij Grove House Mansion Gate Drive Leeds LS7 4DN T +44 (0)113 262 0000 F +44 (0)113 262 0737 E [email protected] Report Status: Rev 1 Job No: 692900 Name Signature Date Prepared By: Mandy Surradge Checked By: Ian Paterson Approved By: Mark Howard © Grontmij This document is a Grontmij confidential document; it may not be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, photocopying, recording or otherwise disclosed in whole or in part to any third party without our express prior written consent. It should be used by you and the permitted discloses for the purpose for which it has been submitted and for no other. States of Jersey Transport and Technical Services 1 Jersey DAP 692900 Needs Report States of Jersey Transport and Technical Services 1 INTRODUCTION ............................................................................................... 5 2 DESCRIPTION OF DRAINAGE AREA ............................................................. 6 3 SCOPE OF WORK ........................................................................................... 7 4 INFILTRATION STUDY .................................................................................... 9 4.1 INFILTRATION ASSESSMENT ........................................................................ 9 4.2 INFILTRATION LOCATIONS ........................................................................... -

Jersey's Military Landscape

Unlock the Island with Jersey Heritage audio tours that if the French fleet was to leave 1765 with a stone vaulted roof, to St Malo, the news could be flashed replace the original structure (which from lookout ships to Mont Orgueil (via was blown up). It is the oldest defensive Grosnez), to Sark and then Guernsey, fortification in St Ouen’s Bay and, as where the British fleet was stationed. with others, is painted white as a Tests showed that the news could navigation marker. arrive in Guernsey within 15 minutes of the French fleet’s departure! La Rocco Tower F 04 Standing half a mile offshore at St Ouen’s Bay F 02, 03, 04 and 05 the southern end of St Ouen’s Bay In 1779, the Prince of Nassau attempted is La Rocco Tower, the largest of to land with his troops in St Ouen’s Conway’s towers and the last to be Jersey’s spiritual Jersey’s maritime bay but found the Lieutenant built. Like the tower at Archirondel landscape Governor and the Militia waiting for it was built on a tidal islet and has a landscape Immerse Download the FREE audio tour Immerse Download the FREE audio tour him and was easily beaten back. surrounding battery, which helps yourself in from www.jerseyheritage.org yourself in from www.jerseyheritage.org the history the history However, the attack highlighted the give it a distinctive silhouette. and stories and stories need for more fortifications in the area of Jersey of Jersey and a chain of five towers was built in Portelet H 06 the bay in the 1780s as part of General The tower on the rock in the middle Supported by Supported by Henry Seymour Conway’s plan to of the bay is commonly known as Tourism Development Fund Tourism Development Fund fortify the entire coastline of Jersey.