Democracydemocracy

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Hbeat60a.Pdf

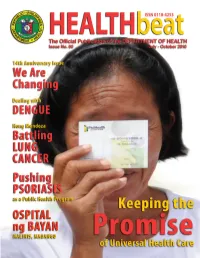

2 HEALTHbeat I July - August 2010 HEALTH exam eeny, meeny, miney, mo... _____ 1. President Noynoy Aquino’s platform on health is called... a) Primary Health Care b) Universal Health Care c) Well Family Health Care _____ 2. Dengue in its most severe form is called... a) dengue fever b) dengue hemorrhagic fever c) dengue shock syndrome _____ 3. Psoriasis is... a) an autoimmune disease b) a communicable disease c) a skin disease _____ 4. Disfigurement and disability from Filariasis is due to... a) mosquitoes b) snails c) worms _____ 5. A temporary family planning method based on the natural effect of exclusive breastfeeding is... a) Depo-Provera b) Lactational Amenorrhea c) Tubal Ligation _____ 6. The creamy yellow or golden substance that is present in the breasts before the mature milk is made is... a) Colostrum b) Oxytocin c) Prolactin _____ 7. The pop culture among the youth that rampantly express depressing words through music, visual arts and the Internet is called... a) EMO b) Jejemon c) Badingo _____ 8. The greatest risk factor for developing lung cancer is... a) Human Papilloma Virus b) Fats c) Smoking _____ 9. In an effort to further improve health services to the people and be at par with its private counterparts, Secretary Enrique T. Ona wants the DOH Central Office and two or three pilot DOH hospitals to get the international standard called... a) ICD 10 b) ISO Certification c) PS Mark _____ 10. PhilHealth’s minimum annual contribution is worth... a) Php 300 b) Php 600 c) Php 1,200 Answers on Page 49 July - August 2010 I HEALTHbeat 3 DEPARTMENT OF HEALTH - National Center for Health Promotion 2F Bldg. -

Between Rhetoric and Reality: the Progress of Reforms Under the Benigno S. Aquino Administration

Acknowledgement I would like to extend my deepest gratitude, first, to the Institute of Developing Economies-JETRO, for having given me six months from September, 2011 to review, reflect and record my findings on the concern of the study. IDE-JETRO has been a most ideal site for this endeavor and I express my thanks for Executive Vice President Toyojiro Maruya and the Director of the International Exchange and Training Department, Mr. Hiroshi Sato. At IDE, I had many opportunities to exchange views as well as pleasantries with my counterpart, Takeshi Kawanaka. I thank Dr. Kawanaka for the constant support throughout the duration of my fellowship. My stay in IDE has also been facilitated by the continuous assistance of the “dynamic duo” of Takao Tsuneishi and Kenji Murasaki. The level of responsiveness of these two, from the days when we were corresponding before my arrival in Japan to the last days of my stay in IDE, is beyond compare. I have also had the opportunity to build friendships with IDE Researchers, from Nobuhiro Aizawa who I met in another part of the world two in 2009, to Izumi Chibana, one of three people that I could talk to in Filipino, the other two being Takeshi and IDE Researcher, Velle Atienza. Maraming salamat sa inyo! I have also enjoyed the company of a number of other IDE researchers within or beyond the confines of the Institute—Khoo Boo Teik, Kaoru Murakami, Hiroshi Kuwamori, and Sanae Suzuki. I have been privilege to meet researchers from other disciplines or area studies, Masashi Nakamura, Kozo Kunimune, Tatsufumi Yamagata, Yasushi Hazama, Housan Darwisha, Shozo Sakata, Tomohiro Machikita, Kenmei Tsubota, Ryoichi Hisasue, Hitoshi Suzuki, Shinichi Shigetomi, and Tsuruyo Funatsu. -

The London School of Economics and Political Science Hegemony

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by LSE Theses Online The London School of Economics and Political Science Hegemony, Transformism and Anti-Politics: Community-Driven Development Programmes at the World Bank Emmanuelle Poncin A thesis submitted to the Department of Government of the London School of Economics for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. London, June 2012. 1 Declaration I certify that the thesis I have presented for examination for the MPhil/PhD degree of the London School of Economics and Political Science is solely my own work other than where I have clearly indicated that it is the work of others (in which case the extent of any work carried out jointly by me and any other person is clearly identified in it). The copyright of this thesis rests with the author. Quotation from it is permitted, provided that full acknowledgement is made. This thesis may not be reproduced without my prior written consent. I warrant that this authorisation does not, to the best of my belief, infringe the rights of any third party. I declare that my thesis consists of 99,559 words. Statement of use of third party for editorial help I can confirm that my thesis was copy edited for conventions of language, spelling and grammar by Patrick Murphy and Madeleine Poncin. 2 Abstract This thesis scrutinises the emergence, expansion, operations and effects of community-driven development (CDD) programmes, referring to the most popular and ambitious form of local, participatory development promoted by the World Bank. -

REFORMS: What Have We Achieved?

REFORMS: What Have We Achieved? Restoring people’s trust in government and democratic PAMANA, an inter-agency project led by the Office To incentivize LGUs in setting transparency and institutions, effective and adequate social services and of the Presidential Adviser on the Peace Process accountability standards, the Performance economic opportunity, and strengthening the (OPAPP), is set up to end the long-standing Challenge Fund was institutionalized. It provides constituencies for reform are the Aquino conflict in the country by building peaceful incentives to Administration’s key objectives as it pursues genuine communities in 1,921 conflict-affected barangays LGUs as a way of recognizing good performance reform in government. So far, significant victories have in 171 municipalities, in 34 provinces. in internal housekeeping, and in the alignment of been achieved, particularly in the areas of anti- local development investment programs with corruption, the peace process, and local governance. national development goals. Many reform advocates acknowledge these gains, and Through the All-Out-War, All-Out-Peace, All-Out- are calling for the needed institutional-legal support Justice Policy of PNoy, the government extends Similarly, the Seal of Good Housekeeping for Local and transformational leadership that can keep the ball Governments is awarded to LGUs that promote the work for peace by bringing to justice rolling so to speak even beyond 2016. and practice openness, transparency, and perpetrators of atrocities. President Aquino accountability. Local legislation, development What has been achieved so far? The following announced the pursuit of “all-out justice” in planning, resource generation, resource allocation provides general description of these reforms. -

Focus on the Philippines Yearbook 2010

TRANSITIONS Focus on the Philippines Yearbook 2010 FOCUS ON THE GLOBAL SOUTH Published by the Focus on the Global South-Philippines #19 Maginhawa Street, UP Village, Diliman, Quezon City, Philippines Copyright@2011 By Focus on the Global South-Philippines All rights reserved. The contents of this publication may be reproduced, quoted or used as reference provided that Focus, as publisher, and the writers, will be duly recognized as the proper sources. Focus would appreciate receiving a copy of the text in which contents of this publication have been used or cited. Statistics and other data with acknowledged other sources are not properties of Focus Philippines, and thus permission for their use in other publication should be coordinated with the pertinent owners/offices. Editor Clarissa V. Militante Assistant Editor Carmen Flores-Obanil Lay-out and Design Amy T. Tejada Contributing Writers Walden Bello Jenina Joy Chavez Jerik Cruz Prospero de Vera Herbert Docena Aya Fabros Mary Ann Manahan Clarissa V. Militante Carmen Flores-Obanil Dean Rene Ofreneo Joseph Purruganan Filomeno Sta. Ana Researcher of Economic Data Cess Celestino Photo Contributions Jimmy Domingo Lina Sagaral Reyes Contents ABOUT THE WRITERS OVERVIEW 1 CHAPTER 1: ELECTIONS 15 Is Congress Worth Running for? By Representative Walden Bello 17 Prosecuting GMA as Platform By Jenina Joy Chavez 21 Rating the Candidates: Prosecution as Platform Jenina Joy Chavez 27 Mixed Messages By Aya Fabros 31 Manuel “Bamba” Villar: Advertising his Way to the Presidency By Carmina Flores-Obanil -

ISSN 2094-9383 a Quarterly Magazine of the City Government of Naga Bikol, Philippines New ISSN 2094-9383 JOHN G

ISSN 2094-9383 A Quarterly Magazine of the City Government of Naga Bikol, Philippines New ISSN 2094-9383 JOHN G. BONGAT Advocacy Mayor GABRIEL H. BORDADO, JR. of a Vice Mayor Jose B. Perez Editor (on leave) Strong Alec Francis A. Santos Leadership Executive Editor Jason B. Neola Managing Editor NAGA IS DEFINED by an empowered and a more liveable community. A City we can truly Reuel M. Oliver Florencio T. Mongoso, Jr. responsible citizenry in action. call Maogmang Naga. A happy place inhabited by a happy people. Allen L. Reondanga Editorial Consultants This is the essence behind KKDK, the new advocacy of a strong leadership under Mayor These ideals are summed up in his first State of Jan Rev L. Davila John G. Bongat that inspires Nagueños to develop the City Report delivered on January 25. His main Stephen V. Prestado Layout Artists in their heart and mind a culture of cleanliness message is everyone, young or old, rich or poor, is (Kalinigan), peace (Katoninongan), and order part and parcel of the City’s life and future with the Ray John B. Ubaldo 2 (Disiplina). These, he believes, are the essential bounden duty to “H ELP your CiTy”, as everyone Graphic Artist takes part in defining Naga’s future today. ingredients (Kaipuhan) towards the attainment of Contents Randy Villaflor Jose B. Collera Photographers Albert F. Cecilio Highlights Alnor Roger Alcala Editorial Assistants STATE OF THE CITY REPORT (Jul - Dec 2010) Mayor JB delivers first SOCR This magazine is published by the City Government of Naga thru the 7 City Publications and External SALOG KAN BUHAY Relations Office (CPERO), with Broadbased support for Editorial Office at 1st floor, DOLE Naga River Project affirmed Bldg., City Hall Complex, J. -

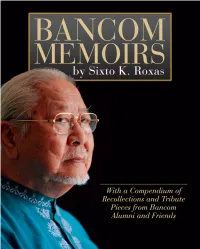

With a Compendium of Recollections and Tribute Pieces from Bancom Alumni and Friends

The ebook version of this book may be downloaded at www.xBancom.com This Bancom book project was made possible by the generous support of mr. manuel V. Pangilinan. The book launching was sponsored by smart infinity copyright © 2013 by sixto K. roxas Bancom memoirsby sixto K. roxas With a Compendium of Recollections and Tribute Pieces from Bancom Alumni and Friends Edited by eduardo a. Yotoko Published by PLDT-smart Foundation, inc and Bancom alumni, inc. (BaLi) contents Foreword by Evelyn R. Singson 5 Foreword by Francis G. Estrada 7 Preface 9 Prologue: Bancom and the Philippine financial markets 13 chapter 1 Bancom at its 10th year 24 chapter 2 BTco and cBTc, Bliss and Barcelon 28 chapter 3 ripe for investment banking 34 chapter 4 Founding eDF 41 chapter 5 organizing PDcP 44 chapter 6 childhood, ateneo and social action 48 chapter 7 my development as an economist 55 chapter 8 Practicing economics at central Bank and PnB 59 chapter 9 corporate finance at Filoil 63 chapter 10 economic planning under macapagal 71 chapter 11 shaping the development vision 76 chapter 12 entering the money market 84 chapter 13 creating the Treasury Bill market 88 chapter 14 advising on external debt management 90 chapter 15 Forming a virtual merchant bank 103 chapter 16 Functional merger with rcBc 108 chapter 17 asean merchant banking network 112 chapter 18 some key asian central bankers 117 chapter 19 asia’s star economic planners 122 chapter 20 my american express interlude 126 chapter 21 radical reorganization and BiHL 136 chapter 22 Dewey Dee and the end of Bancom 141 chapter 23 The total development company components 143 chapter 24 a changed life-world 156 chapter 25 The sustainable development movement 167 chapter 26 The Bancom university of experience 174 chapter 27 summing up the legacy 186 Photo Folio 198 compendium of recollections and Tribute Pieces from Bancom alumni and Friends 205 4 Bancom memoirs Bancom was absorbed by union Bank in 1981. -

Vol. 5 No. 3 July – Sept 2013

Warm Naga SMILES! This year, we celebrate the 303rd year of enduring devotion to Our Lady of Peñafrancia, our Ina. For more than 300 years, and through periods of prosperity, conflicts and calamities, we have never failed to celebrate our faith as a people. The month of September has become a month for Bicolanos all over the globe to gather and pay homage to the Patroness of Bicolandia. This revered tradition reflects our devotion not only to our faith but also to our sense of unity and solidarity, as evidenced by the Nagueños’ continuous support of our leadership and initiatives. The start of July marked the fresh mandate of our new Sangguniang Panlungsod and the City Government’s renewed vow to uphold the principles of good governance that have become an integral part of our administration’s core values. More than three years ago, we started our journey with the idea of good and effective governance as cornerstones of our administration. Three years on, that belief was validated with Team Naga’s success at the ballots. Anchored on our priorities H2ELP your CiTy: health and nutrition, housing and urban poor, education, arts, culture and sports development, livelihood, employment and human development, peace and order and public safety, cleanliness and environment protection, transparency, accountability and good governance, we sought to initiate and implement programs and projects aimed at improving the quality of life in our city. To that end, we shall continue and intensify our efforts, upholding the oaths we took as public officials. My fellow Nagueños, you have once again expressed your sentiments and given us your trust and confidence. -

State of the Nation Address of His Excellency Benigno S. Aquino III President of the Philippines to the Congress of the Philippines

State of the Nation Address of His Excellency Benigno S. Aquino III President of the Philippines To the Congress of the Philippines [This is an English translation of the speech delivered at the Session Hall of the House of Representatives, Batasang Pambansa Complex, Quezon City, on July 27, 2015] Thank you, everyone. Please sit down. Before I begin, I would first like to apologize. I wasn’t able to do the traditional processional walk, or shake the hands of those who were going to receive me, as I am not feeling too well right now. Vice President Jejomar Binay; Former Presidents Fidel Valdez Ramos and Joseph Ejercito Estrada; Senate President Franklin Drilon and members of the Senate; Speaker Feliciano Belmonte, Jr. and members of the House of Representatives; Chief Justice Maria Lourdes Sereno and our Justices of the Supreme Court; distinguished members of the diplomatic corps; members of the Cabinet; local government officials; members of the military, police, and other uniformed services; my fellow public servants; and, to my Bosses, my beloved countrymen: Good afternoon to you all. [Applause] This is my sixth SONA. Once again, I face Congress and our countrymen to report on the state of our nation. More than five years have passed since we put a stop to the culture of “wang-wang,” not only in our streets, but in society at large; since we formally took an oath to fight corruption to eradicate poverty; and since the Filipino people, our bosses, learned how to hope once more. My bosses, this is the story of our journey along the Straight Path. -

Philippines: Social Welfare and Development Reform Project

PHILIPPINES Social Welfare and Development Reform Project Report No. 137065 JUNE 27, 2019 © 2019 International Bank for Reconstruction This work is a product of the staff of The World RIGHTS AND PERMISSIONS and Development / The World Bank Bank with external contributions. The findings, The material in this work is subject to copyright. 1818 H Street NW interpretations, and conclusions expressed in Because The World Bank encourages Washington DC 20433 this work do not necessarily reflect the views of dissemination of its knowledge, this work may be Telephone: 202-473-1000 The World Bank, its Board of Executive reproduced, in whole or in part, for Internet: www.worldbank.org Directors, or the governments they represent. noncommercial purposes as long as full attribution to this work is given. Attribution—Please cite the work as follows: The World Bank does not guarantee the World Bank. 2019. Philippines—Social Welfare accuracy of the data included in this work. The Any queries on rights and licenses, including and Development Reform Project. Independent boundaries, colors, denominations, and other subsidiary rights, should be addressed to Evaluation Group, Project Performance information shown on any map in this work do World Bank Publications, The World Bank Assessment Report 137065. Washington, DC: not imply any judgment on the part of The Group, 1818 H Street NW, Washington, DC World Bank. World Bank concerning the legal status of any 20433, USA; fax: 202-522-2625; e-mail: territory or the endorsement or acceptance of [email protected]. -

Governing Social Security: Economic Crisis and Reform in Indonesia, The

ABSTRACT How do newly industrializing countries in Asia reform their social security programs after the 1997 financial crisis? Going beyond previous studies whose concern were on the relative decline of the welfare state in the midst of global economic competition, this study identifies that after crisis Indonesia, the Philippines and Singapore experienced different shifts in their structure of provision of social security benefits. The shifts vary on two important dimensions of social security provisions: the benefit level and the political control of the state over the private sector. In Indonesia there was a shift that eroded benefit level and strengthened the state’s political control over the private sector. In the Philippines there was a shift that improved benefit level and weakened state control over the private sector. Meanwhile in Singapore the shift improved benefit level yet at the expense of deeper penetration of state control over the private sector. This study asks: what explains the variation in the shifts in the dimensions of social security provisions in Indonesia, the Philippines and Singapore after the 1997 financial crisis? Such variation, I argue, cannot be explained with the usual explanatory variables: fiscal constraints at the national level, the ranking of economies in the global competition, or the intervention of international financial institutions. This economic context after financial crisis only affect the initial proposal of the reform, i.e. the degree ii of dramaticness of change proposed for the social security reform. Once the reform proposal is advanced, however, it was domestic politics that matter more, reshaping the proposal and thus the reform output. -

Infusing Reform in Elections

INFUSING REFORM IN ELECTIONS The Partisan Electoral Engagement of Reform Movements in Post-Martial Law Philippines Ateneo School of Government (ASoG) Paciico Ortiz Hall Fr. Arrupe Road, Social Development Complex Ateneo de Manila University Campus Katipunan Avenue, Loyola Heights Quezon City 1108 Telefax : (632) 920-29-20 Local line : (632) 426-60-01 local 4644 Email : [email protected] Website : www.asg.ateneo.edu Friedrich-Ebert-Stiftung (FES) Philippine Ofice Unit 2601, Discovery Centre #25 ADB Avenue, Ortigas Center Pasig City 1600 Tel : (632) 637-71-86 | (632) 634-69-19 Fax : (632) 632-0697 Website : www.fes.org.ph Printed and bound in the Philippines INFUSING REFORM IN ELECTIONS The Partisan Electoral Engagement of Reform Movements in Post-Martial Law Philippines JOY ACERON Case Writers RAFAELA MAE DAVID GLENFORD LEONILLO VALERIE BUENAVENTURA POLITICAL DEMOCRACY AND REFORM (PODER) Infusing Reform in Elections The Partisan Electoral Engagement of Reform Movements in Post-Martial Law Philippines © 2012 Ateneo School of Government (ASoG) Friedrich-Ebert-Stiftung (FES) Philippine Ofice The views expressed in this book are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of ASoG and FES. ISBN: 978-971-92495-8-0 All rights reserved. No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any manner whatsoever without written permission except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles and reviews. Photos, news clippings, video grabs, newspaper and Internet stories used are copyright of their authors