On the Kinshasa-Brazzaville Border

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

089 La Politique Idigene in the History of Bangui.Pdf

La polit...iq,u:e indigene in t...he history o£ Bangui William J. Samarin impatltntly awaiting tht day when 1 Centrlllfricu one wHI bt written. But it must bt 1 history, 1 rtlltned argument biSed 01 Peaceful beginnings carefully sifted fact. Fiction, not without its own role, ciMot be No other outpost of' European allowtd to rtplace nor be confused with history. I mm ne colonization in central Africa seems to have atttmpt at 1 gentral history of the post, ner do I inttgratt, had such a troubled history as that of' except in 1 small way, the history of Zongo, 1 post of the Conge Bangui, founded by the French in June 1889. Frte State just across tht river ud foundtd around the nme Its first ten or fifteen years, as reported by timt. Chronolo;cal dttlils regarding tht foundation of B~ngui ll't the whites who lived them, were dangerous to be found in Cantoumt (1986),] and uncertain, if' not desperate) ones. For a 1 time there was even talk of' abandoning the The selection of' the site for the post. that. Albert Dolisie named Bangui was undoubtedly post or founding a more important one a little further up the Ubangi River. The main a rational one. This place was not, to beiin problem was that of' relations with the local with, at far remove from the last. post at. Modzaka; it. was crucial in those years to be people •. The purpose of' the present study is able to communicate from one post to to describe this turbulent period in Bangui's another reasonably well by canoe as well as history and attempt to explain it. -

Cameroon's Infrastructure: a Continental Perspective

Public Disclosure Authorized COUNTRY REPORT Cameroon’s Infrastructure: Public Disclosure Authorized A Continental Perspective Carolina Dominguez-Torres and Vivien Foster Public Disclosure Authorized JUNE 2011 Public Disclosure Authorized © 2011 The International Bank for Reconstruction and Development / The World Bank 1818 H Street, NW Washington, DC 20433 USA Telephone: 202-473-1000 Internet: www.worldbank.org E-mail: [email protected] All rights reserved A publication of the World Bank. The World Bank 1818 H Street, NW Washington, DC 20433 USA The findings, interpretations, and conclusions expressed herein are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of the Executive Directors of the International Bank for Reconstruction and Development / The World Bank or the governments they represent. The World Bank does not guarantee the accuracy of the data included in this work. The boundaries, colors, denominations, and other information shown on any map in this work do not imply any judgment on the part of The World Bank concerning the legal status of any territory or the endorsement or acceptance of such boundaries. Rights and permissions The material in this publication is copyrighted. Copying and/or transmitting portions or all of this work without permission may be a violation of applicable law. The International Bank for Reconstruction and Development / The World Bank encourages dissemination of its work and will normally grant permission to reproduce portions of the work promptly. For permission to photocopy or reprint any part of this work, please send a request with complete information to the Copyright Clearance Center Inc., 222 Rosewood Drive, Danvers, MA 01923 USA; telephone: 978-750-8400; fax: 978-750-4470; Internet: www.copyright.com. -

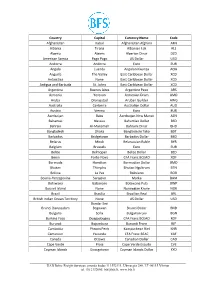

Diversity Visa Program, DV 2019-2021: Number of Entries During Each Online Registration Period by Region and Country of Chargeability

Diversity Visa Program, DV 2019-2021: Number of Entries During Each Online Registration Period by Region and Country of Chargeability The totals below DO NOT represent the number of diversity visas issued nor the number of selected entrants Countries marked with a "0" indicate that there were no entrants from that country or area. Countries marked with "N/A" were typically not eligible for that program year. FY 2019 FY 2020 FY 2021 Region Foreign State of Chargeabiliy Entrants Derivatives Total Entrants Derivatives Total Entrants Derivatives Total Africa Algeria 227,019 123,716 350,735 252,684 140,422 393,106 221,212 129,004 350,216 Africa Angola 17,707 25,543 43,250 14,866 20,037 34,903 14,676 18,086 32,762 Africa Benin 128,911 27,579 156,490 150,386 26,627 177,013 92,847 13,149 105,996 Africa Botswana 518 462 980 552 406 958 237 177 414 Africa Burkina Faso 37,065 7,374 44,439 30,102 5,877 35,979 6,318 2,591 8,909 Africa Burundi 20,680 16,295 36,975 22,049 19,168 41,217 12,287 11,023 23,310 Africa Cabo Verde 1,377 1,272 2,649 894 778 1,672 420 312 732 Africa Cameroon 310,373 147,979 458,352 310,802 165,676 476,478 150,970 93,151 244,121 Africa Central African Republic 1,359 893 2,252 1,242 636 1,878 906 424 1,330 Africa Chad 5,003 1,978 6,981 8,940 3,159 12,099 7,177 2,220 9,397 Africa Comoros 296 224 520 293 128 421 264 111 375 Africa Congo-Brazzaville 21,793 15,175 36,968 25,592 19,430 45,022 21,958 16,659 38,617 Africa Congo-Kinshasa 617,573 385,505 1,003,078 924,918 415,166 1,340,084 593,917 153,856 747,773 Africa Cote d'Ivoire 160,790 -

The DRC Seed Sector

A Quarter-Billion Dollar Industry? The DRC Seed Sector BRIEF DESCRIPTION: Compelling investment opportunities exist for seed companies and seed start-ups in the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC). This document outlines the market potential and consumer demand trends in the DRC and highlights the high potential of seed production in the country. 1 Executive Summary Compelling investment opportunities exist for seed companies and seed start-ups in the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC). This document outlines the market potential and consumer demand trends in the DRC and highlights the high potential of seed production in the country. The DRC is the second largest country in Africa with over 80 million hectares of agricultural land, of which 4 to 7 million hectares are irrigable. Average rainfall varies between 800 mm and 1,800 mm per annum. Bimodal and extended unimodal rainfall patterns allow for two agricultural seasons in approximately 75% of the country. Average relative humidity ranges from 45% to 90% depending on the time of year and location. The market potential for maize, rice and bean seed in the DRC is estimated at $191 million per annum, of which a mere 3% has been exploited. Maize seed sells at $3.1 per kilogramme of hybrid seed and $1.6 per kilogramme of OPV seed, a higher price than in Tanzania, Kenya, Uganda and Zambia. Seed-to-grain ratios are comparable with regional benchmarks at 5.5:1 for hybrid maize seed and 5.0:1 for OPV maize seed. The DRC is defined by four relatively distinct sales zones, which broadly coincide with the country’s four principal climate zones. -

TRAVEL ITINERARY Republic of Congo (Congo Brazzaville)

P TRAVEL ITINERARY Republic of Congo (Congo Brazzaville) 7-NIGHTS DISCOVERY 2017 – 31 March 2018 BELLINGHAM SAFARIS | TEL: +27-(0)21-783-4380 | WWW.BELLINGHAMSAFARIS.COM 2 REPUBLIC OF CONGO 7-NIGHTS DISCOVERY PACKAGE Your tour at a glance… Day Location Accommodation Day 1 Odzala National Park Ngaga Camp Day 2 Odzala National Park Ngaga Camp Day 3 Odzala National Park Ngaga Camp Day 4 Odzala National Park Mboko Camp Day 5 Odzala National Park Lango Camp Day 6 Odzala National Park Lango Camp Day 7 Odzala National Park Mboko Camp Day 8 Day of Departure Odzala aims to use responsible Lowland Gorilla-orientated tourism as a catalyst to spread the rainforest conservation message both globally and locally. The Republic of Congo (Brazzaville) is a surprising central African gem with seemingly endless pristine tropical forest and fingers of moist savannah covering its interior. Odzala-Kokoua National Park, in the Congo's remote north, is one of Africa's oldest national parks, having been proclaimed by the French administration in 1935. It covers some 13 600 square kilometres (1 360 million hectares) of pristine rainforest and is an integral part of both the Congo Basin and the TRIDOM Transfrontier Park overlapping Gabon, Congo and Central African Republic. The Odzala experience is undertaken from three intimate, sensitively constructed camps that leave as light a footprint as possible and blend into this remote forest environment: Lango Camp on the edge of the savannah, Mboko Camp with access to the Lekoli and Mambili Rivers, and Ngaga Camp in the heart of a marantaceae forest, where you will have excellent chances of viewing Western Lowlands Gorilla. -

Context in the Republic of Congo

CONTEXT UNICEF REPubLIC OF CONGO DEMOGRAPHICS CONTEXT IN THE AND DEVELOPMENT The Republic of Congo has a young population: 47% of its over 5 million REPUBLIC OF CONGO inhabitants are under the age of 18 years. Nearly 62% of the total population lives in the two largest cities, Brazzaville and The Republic of Congo is located on the issue of political governance. Between Pointe-Noire. western coast of Central Africa. It is bordered 1960 and 1992, the history of the Congo Congo ranks 154th out of 188 countries by Gabon, Cameroon, Central African Republic, was characterized by numerous episodes globally on the Human Development Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC) and of violence and socio-political crises, which Index and 8th out of 48 countries in Sub- Angola, as well as the Atlantic Ocean to the led to several regime changes. The country Saharan Africa. This puts it in the medium south-west. The capital city, Brazzaville, lies on has held multi-party elections since 1992, human development category. the Congo River in the south of the country, but, following a civil war, the democratically just across the border from Kinshasa, the elected government was ousted in 1997. Some 35% of the population in Congo capital of DRC. lived in poverty in 2016 according to the Over the past decade, Congo has benefited World Bank. Evidence from Multiple and Formerly part of the French colony of from a consolidation of peace and security, Overlapping Deprivation Analysis (MODA) Equatorial Africa, the Republic of Congo was which has led to political stability (presidential has shown that 61% of children under the established in 1958 and gained independence elections in 2009 and legislative in 2012). -

Global Suicide Rates and Climatic Temperature

SocArXiv Preprint: May 25, 2020 Global Suicide Rates and Climatic Temperature Yusuke Arima1* [email protected] Hideki Kikumoto2 [email protected] ABSTRACT Global suicide rates vary by country1, yet the cause of this variability has not yet been explained satisfactorily2,3. In this study, we analyzed averaged suicide rates4 and annual mean temperature in the early 21st century for 183 countries worldwide, and our results suggest that suicide rates vary with climatic temperature. The lowest suicide rates were found for countries with annual mean temperatures of approximately 20 °C. The correlation suicide rate and temperature is much stronger at lower temperatures than at higher temperatures. In the countries with higher temperature, high suicide rates appear with its temperature over about 25 °C. We also investigated the variation in suicide rates with climate based on the Köppen–Geiger climate classification5, and found suicide rates to be low in countries in dry zones regardless of annual mean temperature. Moreover, there were distinct trends in the suicide rates in island countries. Considering these complicating factors, a clear relationship between suicide rates and temperature is evident, for both hot and cold climate zones, in our dataset. Finally, low suicide rates are typically found in countries with annual mean temperatures within the established human thermal comfort range. This suggests that climatic temperature may affect suicide rates globally by effecting either hot or cold thermal stress on the human body. KEYWORDS Suicide rate, Climatic temperature, Human thermal comfort, Köppen–Geiger climate classification Affiliation: 1 Department of Architecture, Polytechnic University of Japan, Tokyo, Japan. -

International Currency Codes

Country Capital Currency Name Code Afghanistan Kabul Afghanistan Afghani AFN Albania Tirana Albanian Lek ALL Algeria Algiers Algerian Dinar DZD American Samoa Pago Pago US Dollar USD Andorra Andorra Euro EUR Angola Luanda Angolan Kwanza AOA Anguilla The Valley East Caribbean Dollar XCD Antarctica None East Caribbean Dollar XCD Antigua and Barbuda St. Johns East Caribbean Dollar XCD Argentina Buenos Aires Argentine Peso ARS Armenia Yerevan Armenian Dram AMD Aruba Oranjestad Aruban Guilder AWG Australia Canberra Australian Dollar AUD Austria Vienna Euro EUR Azerbaijan Baku Azerbaijan New Manat AZN Bahamas Nassau Bahamian Dollar BSD Bahrain Al-Manamah Bahraini Dinar BHD Bangladesh Dhaka Bangladeshi Taka BDT Barbados Bridgetown Barbados Dollar BBD Belarus Minsk Belarussian Ruble BYR Belgium Brussels Euro EUR Belize Belmopan Belize Dollar BZD Benin Porto-Novo CFA Franc BCEAO XOF Bermuda Hamilton Bermudian Dollar BMD Bhutan Thimphu Bhutan Ngultrum BTN Bolivia La Paz Boliviano BOB Bosnia-Herzegovina Sarajevo Marka BAM Botswana Gaborone Botswana Pula BWP Bouvet Island None Norwegian Krone NOK Brazil Brasilia Brazilian Real BRL British Indian Ocean Territory None US Dollar USD Bandar Seri Brunei Darussalam Begawan Brunei Dollar BND Bulgaria Sofia Bulgarian Lev BGN Burkina Faso Ouagadougou CFA Franc BCEAO XOF Burundi Bujumbura Burundi Franc BIF Cambodia Phnom Penh Kampuchean Riel KHR Cameroon Yaounde CFA Franc BEAC XAF Canada Ottawa Canadian Dollar CAD Cape Verde Praia Cape Verde Escudo CVE Cayman Islands Georgetown Cayman Islands Dollar KYD _____________________________________________________________________________________________ -

Apirg/17 – Wp/10B Organisation De L'aviation Civile

APIRG/17 – WP/10B ORGANISATION DE L’AVIATION CIVILE INTERNATIONALE DIX-SEPTIEME REUNION DU GROUPE DE PLANIFICATION ET DE MISE EN OEUVRE DE LA REGION AFRIQUE – OCEAN INDIEN (APIRG/17) (Ouagadougou, 2-6 aout, 2010) Point 4: Examen et mise à jour de la liste des carences dans les domaines de la navigation aérienne 4.1 Communications, Navigation et Surveillance (CNS) Examen et mise à jour de la liste des carences dans le domaine CNS (Présentée par le Secrétariat) SOMMAIRE Cette note de travail présente les carences qui affectent les télécommunications aéronautiques dans la Région AFI, pour examen et mise à jour par le groupe APIRG. La suite a donner par la réunion se trouve au paragraphe 3. Références : [1] – Rapport de la réunion CNS/SG/3 (Principale référence) [2] – Rapport de la réunion CNS/SG/2 [3] – Rapport de la réunion APIRG/16 [4] – Rapport de la réunion spéciale AFI RAN (2008) (Doc 9930) [5] – Annexe 10 a la Convention relative à l’Aviation civile internationale Note: Les références [1], [2], [3] et [4] sont accessibles à partir du site Internet : http://www.icao.int. Objectifs stratégiques: A, D. 1. INTRODUCTION 1.1. La réunion CNS/SG/3 a examine la liste des carences qui affectent le fonctionnement des telecommunications aéronautiques dans la Région AFI, telle qu’elle a été préparée par le Secrétariat sur la base des renseignements reçus des Etats, des organisations internationales pertinentes et des rapports de missions de l’OACI auprès des Etats. Le Secrétariat a aussi effectue une coordination avec les Etats et organisations internationaux pour valider les renseignements fournis a la réunion CNS/SG/3, et a recueilli des renseignements complémentaires pour valider l’état de mise en œuvre des éléments CNS. -

Panoptic Urbanism: Techniques of State Power and Pacification in Colonial Algiers Elena Becerril Salas

Panoptic Urbanism: Techniques of State power and Pacification in Colonial Algiers Elena Becerril Salas The 1958 Plan de Constantine and Mayor Chevallier’s 1954 “Battle for Housing” initiative for colonial Algiers embraced “welfare colonialism” as a vital instrument to the pacification of Algerian unrest caused by the rise of unemployment, informal settlements and anti-colonial resistance. The rationalization of modernity and order through architectural design epitomize two dominant state mechanisms persistently utilized for social ordering. This papers examines how colonial France sought to legitimize and retain state control of Algiers through the ‘the rhetoric of progress’ in addition to panoptic design during the 1930s-1950s. In 1840, General Marshal Thomas Bugeaud of France was left with the task of pacifying the Algerian insurrection led by Abdel Kader’s Berber and the Arab tribal army. General Bugeaud begins to seize control of Algerian insurgents by the utilization of rapid mobile task forces assigned to murder civilians, decimate villages and seize Algerian territorial land (Weizman, 2006). Colonial French rule over Algeria during the late 1800s was characterized by the destruction of ‘mosques, architectural patrimony and historical buildings within the lower medina area’ (Djiar 172, 2009). The 1930s defined a new phase in colonial French rule within Algeria. Pacification methods that emphasized benevolent cultural assimilation and ‘progressive’ urbanism replaced the brutal French military initiatives of the 1840s. This essay traces the history of French imperial rhetoric and colonial housing reform throughout the 1930s and 1950s within three sections, The first section examines the ideological impact the 1931 International Conference of Colonial Urbanism and the 1944 Brazzaville Conference had on colonial reform and ideology. -

The Relationship Between Ecosystem Services and Urban Phytodiversity Is Be- G.M

Open Journal of Ecology, 2020, 10, 788-821 https://www.scirp.org/journal/oje ISSN Online: 2162-1993 ISSN Print: 2162-1985 Relationship between Urban Floristic Diversity and Ecosystem Services in the Moukonzi-Ngouaka Neighbourhood in Brazzaville, Congo Victor Kimpouni1,2* , Josérald Chaîph Mamboueni2, Ghislain Bileri-Bakala2, Charmes Maïdet Massamba-Makanda2, Guy Médard Koussibila-Dibansa1, Denis Makaya1 1École Normale Supérieure, Université Marien Ngouabi, Brazzaville, Congo 2Institut National de Recherche Forestière, Brazzaville, Congo How to cite this paper: Kimpouni, V., Abstract Mamboueni, J.C., Bileri-Bakala, G., Mas- samba-Makanda, C.M., Koussibila-Dibansa, The relationship between ecosystem services and urban phytodiversity is be- G.M. and Makaya, D. (2020) Relationship ing studied in the Moukonzi-Ngouaka district of Brazzaville. Urban forestry, between Urban Floristic Diversity and Eco- a source of well-being for the inhabitants, is associated with socio-cultural system Services in the Moukonzi-Ngouaka Neighbourhood in Brazzaville, Congo. Open foundations. The surveys concern flora, ethnobotany, socio-economics and Journal of Ecology, 10, 788-821. personal interviews. The 60.30% naturalized flora is heterogeneous and https://doi.org/10.4236/oje.2020.1012049 closely correlated with traditional knowledge. The Guineo-Congolese en- demic element groups are 39.27% of the taxa, of which 3.27% are native to Received: September 16, 2020 Accepted: December 7, 2020 Brazzaville. Ethnobotany recognizes 48.36% ornamental taxa; 28.36% food Published: December 10, 2020 taxa; and 35.27% medicinal taxa. Some multiple-use plants are involved in more than one field. The supply service, a food and phytotherapeutic source, Copyright © 2020 by author(s) and provides the vegetative and generative organs. -

The Addis Ababa Declaration on Community Health in the African Region

THE ADDIS ABABA DECLARATION ON COMMUNITY HEALTH IN THE AFRICAN REGION 1. We, the ministers of health and representatives of Member States, nongovernmental organizations, civil societies, and bilateral and multilateral agencies gathered in Addis Ababa (from 20 to 22 November 2006) for the Joint UNAIDS, UNICEF, World Bank and WHO International Conference on Community Health in the African Region to ensure universal access to quality health care and a healthier future for the African people; 2. Recalling the Alma-Ata Declaration of September 1978 calling on all governments and the world community to protect and promote the health of the people of the world, the previous conferences held in Kinshasa in 1990 on community health financing and in Brazzaville in 1992 on promoting community health development, the pledge made by African Heads of States at the Africa Summit on HIV/AIDS, Tuberculosis and Other Related Infectious Diseases in Abuja in 2001 to allocate at least 15% of national budgets to health by 2015 and the decision of the Heads of States of the African Union in July 2004 in Syrte, Libya to accelerate child survival implementation in the African Region; 3. Acknowledging the link between health, poverty alleviation, peace and security, gender mainstreaming, and the global commitment towards universal access to health care to facilitate the achievement of the Millennium Development Goals; 4. Noting that over 60% of African households live below the poverty line, and that over 60% of African people live in rural to peri-urban communities with limited social infrastructure, deteriorating health services and a high burden of communicable and noncommunicable diseases; 5.