Shell Morphology and Color of the Subtidal Whelk Buccinum Undatum Exhibit Fine-Scaled Spatial Patterns

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

WHELKS Scientific Names: Busycon Canaliculatum Busycon Carica

Colloquial Nicknames: Channeled Whelk Knobbed Whelk WHELKS Scientific names: Busycon canaliculatum Busycon carica Field Markings: The shell of open with their strong muscular foot. As both species is yellow-red or soon as the valves open, even the tiniest orange inside and pale gray amount, the whelk wedges in the sharp edge outside. of its shell, inserts the proboscis and Size: Channeled whelk grows up devours the soft body of the clam. to 8 inches long; knobbed whelk Mating occurs by way of internal grows up to 9 inches long and 4.5 inches wide fertilization; sexes are separate. The egg casing of the whelk is a Habitat: Sandy or muddy bottoms long strand of yellowish, parchment-like disks, resembling a Seasonal Appearance: Year-round necklace - its unique shape is sculpted by the whelk’s foot. Egg cases can be two to three feet long and have 70 to 100 capsules, DISTINGUISHING FEATURES AND each of which can hold 20 to 100 eggs. Newly hatched channeled BEHAVIORS whelks escape from small holes at the top of each egg case with Whelks are large snails with massive shells. The two most their shells already on. Egg cases are sometimes found along common species in Narragansett Bay are the knobbed whelk the Bay shoreline, washed up with the high tide debris. and the channeled whelk. The knobbed whelk is the largest marine snail in the Bay. It Relationship to People is pear-shaped with a flared outer lip and knobs on the shoulder Both channeled and knobbed whelks scavenge and hunt for of its shell. -

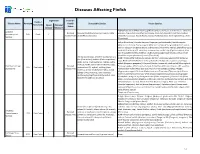

Diseases Affecting Finfish

Diseases Affecting Finfish Legislation Ireland's Exotic / Disease Name Acronym Health Susceptible Species Vector Species Non-Exotic Listed National Status Disease Measures Bighead carp (Aristichthys nobilis), goldfish (Carassius auratus), crucian carp (C. carassius), Epizootic Declared Rainbow trout (Oncorhynchus mykiss), redfin common carp and koi carp (Cyprinus carpio), silver carp (Hypophtalmichthys molitrix), Haematopoietic EHN Exotic * Disease-Free perch (Percha fluviatilis) Chub (Leuciscus spp), Roach (Rutilus rutilus), Rudd (Scardinius erythrophthalmus), tench Necrosis (Tinca tinca) Beluga (Huso huso), Danube sturgeon (Acipenser gueldenstaedtii), Sterlet sturgeon (Acipenser ruthenus), Starry sturgeon (Acipenser stellatus), Sturgeon (Acipenser sturio), Siberian Sturgeon (Acipenser Baerii), Bighead carp (Aristichthys nobilis), goldfish (Carassius auratus), Crucian carp (C. carassius), common carp and koi carp (Cyprinus carpio), silver carp (Hypophtalmichthys molitrix), Chub (Leuciscus spp), Roach (Rutilus rutilus), Rudd (Scardinius erythrophthalmus), tench (Tinca tinca) Herring (Cupea spp.), whitefish (Coregonus sp.), North African catfish (Clarias gariepinus), Northern pike (Esox lucius) Catfish (Ictalurus pike (Esox Lucius), haddock (Gadus aeglefinus), spp.), Black bullhead (Ameiurus melas), Channel catfish (Ictalurus punctatus), Pangas Pacific cod (G. macrocephalus), Atlantic cod (G. catfish (Pangasius pangasius), Pike perch (Sander lucioperca), Wels catfish (Silurus glanis) morhua), Pacific salmon (Onchorhynchus spp.), Viral -

Geometric Morphometric Analysis Reveals That the Shells of Male and Female Siphon Whelks Penion Chathamensis Are the Same Size and Shape Felix Vaux A, James S

MOLLUSCAN RESEARCH, 2017 http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/13235818.2017.1279474 Geometric morphometric analysis reveals that the shells of male and female siphon whelks Penion chathamensis are the same size and shape Felix Vaux a, James S. Cramptonb,c, Bruce A. Marshalld, Steven A. Trewicka and Mary Morgan-Richardsa aEcology Group, Institute of Agriculture and Environment, Massey University, Palmerston North, New Zealand; bGNS Science, Lower Hutt, New Zealand; cSchool of Geography, Environment & Earth Sciences, Victoria University, Wellington, New Zealand; dMuseum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa, Wellington, New Zealand ABSTRACT ARTICLE HISTORY Secondary sexual dimorphism can make the discrimination of intra and interspecific variation Received 11 July 2016 difficult, causing the identification of evolutionary lineages and classification of species to be Final version received challenging, particularly in palaeontology. Yet sexual dimorphism is an understudied research 14 December 2016 topic in dioecious marine snails. We use landmark-based geometric morphometric analysis to KEYWORDS investigate whether there is sexual dimorphism in the shell morphology of the siphon whelk Buccinulidae; conchology; Penion chathamensis. In contrast to studies of other snails, results strongly indicate that there fossil; geometric is no difference in the shape or size of shells between the sexes. A comparison of morphometrics; mating; P. chathamensis and a related species demonstrates that this result is unlikely to reflect a paleontology; reproduction; limitation of the method. The possibility that sexual dimorphism is not exhibited by at least secondary sexual some species of Penion is advantageous from a palaeontological perspective as there is a dimorphism; snail; true whelk rich fossil record for the genus across the Southern Hemisphere. -

Determination of the Abundance and Population Structure of Buccinum Undatum in North Wales

Determination of the Abundance and Population Structure of Buccinum undatum in North Wales Zara Turtle Marine Environmental Protection MSc Redacted version September 2014 School of Ocean Sciences Bangor University Bangor University Bangor Gwynedd Wales LL57 2DG Declaration This work has not previously been accepted in substance for any degree and is not being currently submitted for any degree. This dissertation is being submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirement of the M.Sc. in Marine Environmental Protection. The dissertation is the result of my own independent work / investigation, except where otherwise stated. Other sources are acknowledged by footnotes giving explicit references and a bibliography is appended. I hereby give consent for my dissertation, if accepted, to be made available for photocopying and for inter-library loan, and the title and summary to be made available to outside organisations. Signed: Date: 12/09/2014 i Determination of the Abundance and Population Structure of Buccinum undatum in North Wales Zara Turtle Abstract A mark-recapture study and fisheries data analysis for the common whelk, Buccinum undatum, was undertaken for catches on a commercial fishing vessel operating from The fishing location, north Wales, from June-July 2014. Laboratory experiments were conducted on B.undatum to investigate tag retention rates and behavioural responses after being exposed to a number of treatments. Thick rubber bands were found to have a 100 % tag retention rate after four months. Riddling, tagging and air exposure do not affect the behavioural responses of B.undatum. The mark-recapture study was used to estimate population size and movement. 4007 whelks were tagged with thick rubber bands over three tagging events. -

Preliminary Appraisal of Imposex in Areas Under the Influence of Southern Brazilian Harbors

J. Braz. Soc. Ecotoxicol., v. 2, n. 1, 2007, 73-79 JBSE SETAC – Brazil Preliminary Appraisal of Imposex in Areas Under the Influence of Southern Brazilian Harbors I. B. DE CASTRO,1,2 C. E. BEMVENUTI2 & G. FILLMANN2* 1Laboratório de Zoobentos, Instituto de Ciências do Mar, LABOMAR/UFC, Av. da Abolição, 3207, Bairro Meireles, CEP 60165-081, Fortaleza, CE, Brasil 2Fundação Universidade Federal do Rio Grande, C.P. 474, CEP 96201-900, Rio Grande, RS, Brasil (Received November 1, 2006; Accepted January 10, 2007) ABSTRACT Imposex in gastropod mollusks is an efficient and low-cost biomarker for pollution by organotin compounds. Such substances are typically found in areas with an intense flux of vessels, such as marinas and harbors. This study preliminarily evaluated the occurrence of imposex in Stramonita haemastoma (Linnaeus, 1758) populations along the areas under the influence of the main harbors from southern Brazil (Paranaguá, PR; São Francisco do Sul, SC; Itajaí, SC; and Rio Grande, RS). Although no chemical analyses were performed so far to confirm the presence of organotins, the occurrence of imposex strongly suggests a contamination by these compounds in the studied areas and it is likely that the closest from the harbors (as the main sources) the more contaminated the environment. However, due to the limitations of S. haemastoma, it is important to assess the response of alternative species adapted to mesohaline environments and non-consolidated substrates, in order to make up for the lack of indicator species for some areas such as Patos Lagoon and Itajaí-Açu estuaries. Key words: imposex, Stramonita haemastoma, organotin, estuary, southern Brazil. -

Of Bathybuccinum (Gastropoda:Buccinidae) from The

The malacological society of Japan VENUS (Jap. Jour. Malac.)Rre - Vol. 57, No. 2 {199R>/ 75 84 OriginalArticles zag A new species of Bathybuccinum (Gastropoda:Buccinidae) from the Aleutian Islands Yuri KANToR and M. G. HARAsEwycH A.?VL Severtzov hrstitute of Problems of Evolution, Russian Academy of Sciences. Leninskij Prospec4 33, Moscaw 11ro71 Russia, and Department of invertebrate Zooiogy. Nittionat Museum of Nbturat History, Smithsonian institution. PVbshington, DC 2a560 USA Abstract: Bathybuccinum (Ovulatibuccinunz) clarki new species, is described from bathyal depths off the central Aleutian Islands, This new species is provisienally assigned to the genus Batdybuccinum primarily en the basis of its distinctive triangular operculum with terminal nuclcus, and large osphradium, which are rare features in Buccininae. Conchologi- cally, the new species most closely resembres Buccinum (EpistobuccinumJ epistomium Dall, 1907, which, however, has a typical buccinid eperculum that is large, oval, with a subcentral nucleus. Key words: Neogastropoda, Buccinidae, Batlu,buccinum, North Pacific, new species. Introduction Neogastropods of the family Buccinidae comprise a diverse and abundant component of the subtidal to abyssal fauna of carnivores and scavengers, especially in temperate and polar regions. The rank and composition of this taxon has been subject to widely varying interpretations (e.g. Boss, 1982; Ponder & Waren, 1988; Vaught, 1989), and is still far from resolved. Habe & Sato (1972) divided the northern Pacific Buccinidae into six subfamilies, including the nominotypical subfamily Buccininae. Golikov (1980) mono- graphed the Buccininae, subdividing it into 3 genera, 3 subgenera and 88 species. Tiba and Kosuge (1984) reviewed and illustrated 49 North Pacific species of the genus Buccinum. Most recently, Golikov & Sirenko (1988) proposed a new classification of the subfamily Buccininae, recognizing 5 genera, 23 subgenera and I08 species, all from the boreal region. -

Xoimi AMERICAN COXCIIOLOGY

S31ITnS0NIAN MISCEllANEOUS COLLECTIOXS. BIBLIOGIIAPHY XOimi AMERICAN COXCIIOLOGY TREVIOUS TO THE YEAR 18G0. PREPARED FOR THE SMITHSONIAN INSTITUTION BY . W. G. BINNEY. PART II. FOKEIGN AUTHORS. WASHINGTON: SMITHSONIAN INSTITUTION. JUNE, 1864. : ADYERTISEMENT, The first part of the Bibliography of American Conchology, prepared for the Smithsonian Institution by Mr. Binuey, was published in March, 1863, and embraced the references to de- scriptions of shells by American authors. The second part of the same work is herewith presented to the public, and relates to species of North American shells referred to by European authors. In foreign works binomial authors alone have been quoted, and no species mentioned which is not referred to North America or some specified locality of it. The third part (in an advanced stage of preparation) will in- clude the General Index of Authors, the Index of Generic and Specific names, and a History of American Conchology, together with any additional references belonging to Part I and II, that may be met with. JOSEPH HENRY, Secretary S. I. Washington, June, 1864. (" ) PHILADELPHIA COLLINS, PRINTER. CO]^TENTS. Advertisement ii 4 PART II.—FOREIGN AUTHORS. Titles of Works and Articles published by Foreign Authors . 1 Appendix II to Part I, Section A 271 Appendix III to Part I, Section C 281 287 Appendix IV .......... • Index of Authors in Part II 295 Errata ' 306 (iii ) PART II. FOEEIGN AUTHORS. ( V ) BIBLIOGRxVPHY NOETH AMERICAN CONCHOLOGY. PART II. Pllipps.—A Voyage towards the North Pole, &c. : by CON- STANTiNE John Phipps. Loudou, ITTJc. Pa. BIBLIOGRAPHY OF [part II. FaliricillS.—Fauna Grcenlandica—systematice sistens ani- malia GrcEulandite occidentalis liactenus iudagata, &c., secun dum proprias observatioues Othonis Fabricii. -

Age, Growth, Size at Sexual Maturity and Reproductive Biology of Channeled Whelk, Busycotypus Canaliculatus, in the U.S. Mid-Atlantic

Age, Growth, Size at Sexual Maturity and Reproductive Biology of Channeled Whelk, Busycotypus canaliculatus, in the U.S. Mid-Atlantic October 2015 Robert A. Fisher Virginia Institute of Marine Science Virginia Sea Grant-Affiliated Extension (In cooperation with Bernie’s Conchs) Robert A. Fisher Marine Advisory Services Virginia Institute of Marine Science P.O. Box 1346 Gloucester Point, VA 23062 804/684-7168 [email protected] www.vims.edu/adv VIMS Marine Resource Report No. 2015-15 VSG-15-09 Additional copies of this publication are available from: Virginia Sea Grant Communications Virginia Institute of Marine Science P.O. Box 1346 Gloucester Point, VA 23062 804/684-7167 [email protected] Cover Photo: Robert Fisher, VIMS MAS This work is affiliated with the Virginia Sea Grant Program, by NOAA Office of Sea Grant, U.S. Depart- ment of Commerce, under Grant No. NA10OAR4170085. The views expressed herein do not necessar- ily reflect the views of any of those organizations. Age, Growth, Size at Sexual Maturity and Reproductive Biology of Channeled Whelk, Busycotypus canaliculatus, in the U.S. Mid-Atlantic Final Report for the Virginia Fishery Resource Grant Program Project 2009-12 Abstract The channeled whelk, Busycotypus canaliculatus, was habitats, though mixing is observed inshore along shallow sampled from three in-shore commercially harvested waters of continental shelf. Channeled whelks are the resource areas in the US Mid-Atlantic: off Ocean City, focus of commercial fisheries throughout their range (Davis Maryland (OC); Eastern Shore of Virginia (ES); and and Sisson 1988, DiCosimo 1988, Bruce 2006, Fisher and Virginia Beach, Virginia (VB). -

FAU Institutional Repository

FAU Institutional Repository http://purl.fcla.edu/fau/fauir This paper was submitted by the faculty of FAU’s Harbor Branch Oceanographic Institute. Notice: ©1990 The Bailey-Matthews Shell Museum. This author manuscript appears courtesy of The Nautilus, a peer-reviewed, not-for-profit quarterly published by the non-profit organization The Bailey-Matthews Shell Museum. The published version is available at http://shellmuseum.org/nautilus/index.html and may be cited as: Harasewyeh, M. G. (1990). Studies on bathyal and abyssal buccinidae (Gastropoda: Neogastropoda): 1. Metula fusiformis Clench and Aguayo, 1941. The Nautilus, 104(4), 120-129. o THE NAUTI LUS 104(4):120-129, 1990 Page 120 Studies on Bathyal and Abyssal Buccinidae (Gastropoda: Neogastropoda): 1. Metula fusiformis Clench and Aguayo, 1941 M. G. Harasewych Department of Invertebrate Zoology National Museum of Natura l History Smithsonian Institution Washington , DC 20560, USA ABSTRACT fact that the vast majority of taxa are based exclusively on features of the shell and operculum, supplemented Based on the morphology of the radu la and shell, Metula [u occasionally by observations on radu lar morphology. sifo rmis Clench & Aguayo, 1941 is transferred to the predom inantl y Indo-w estern Pacific genus Manaria . This species occurs Shells of Buccinid ae tend to be simple, and offer few in upper continental slope communities (183- 578 m) of the readily discernible morphological characters. These are Caribbean Sea and the northern coast of South America . The subject to convergence, especia lly in polar regions and holotype was collected dead in 2,633 rn, well below the depth the deep sea, where effects of habitat on shell form are inhabited by this species. -

Predators in Action: Rapa Whelks Vs. Hard Clams

VORTEX PREDATORS IN ACTION: RAPA WHELKS VS. HARD CLAMS INTRODUCTION Rapa whelks (Rapana venosa) are large predatory ma- rine snails (Figure 1). These large snails were discov- Figure 1: An adult rapa ered in the Chesapeake Bay in 1998. Rapa whelks are whelk from the lower native to the marine and estuarine habitats off the coast Chesapeake Bay. This of Japan and Korea. They were introduced to the Black animal’s shell is 165 Sea in the mid 1940s and have since spread from there mm long. ©2002. J. into the Mediterranean, Adriatic, and Aegean Seas. It Harding. is very likely that the Chesapeake Bay population be- gan with the introduction of baby snails from the Black Sea into the waters of the lower Chesapeake Bay in ships’ ballast water. Rapa whelks eat bivalve molluscs. They are generalist predators; that is, they do not require a particular kind of bivalve. They will eat whatever bivalves are avail- able to them. In the lower Chesapeake Bay the poten- tial menu for rapa whelks includes hard clams (Mercenaria mercenaria, Figure 2), mussels (Mytilus Figure 2: Two adult hard clams. These animals are and Geukensia sp.), and oysters (Crassostrea virginica), approximately 80 mm long. ©2003. J. Harding. as well as others. Adult rapa whelks or animals with shells bigger than 75 mm (about the size of a tennis and fishery managers are concerned about the poten- ball) seem to live in the same places that hard clams tial effects that rapa whelk predation might have on live and probably eat them as a main food item. -

Phylogenetic Positions of Some Genera and Species of the Family Buccinidae (Gastropoda: Mollusca) from China Based on Ribosomal RNA and COI Sequences

CORE Metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk Provided by Springer - Publisher Connector Article SPECIAL TOPIC: Change of Biodiversity Patterns in Coastal Zone July 2013 Vol.58 No.19: 23152322 doi: 10.1007/s11434-013-5922-z Phylogenetic positions of some genera and species of the family Buccinidae (Gastropoda: Mollusca) from China based on ribosomal RNA and COI sequences HOU Lin1*, DAHMS Hans-Uwe2, DONG ChangYong1, CHEN YiFei1, HOU HaoChen1, YANG WanXi3 & ZOU XiangYang4 1 College of Life Science, Liaoning Normal University, Dalian 116081, China; 2 Sangmyung University, Green Life Science Department, 7 Hongji-dong, Jongno-gu, Seoul 110-743, Korea; 3 College of Life Sciences, Zhejiang University, Hangzhou 310058, China; 4 Department of Biotechnology, Dalian Medical University, Dalian 116044, China Received January 21, 2013; accepted March 27, 2013 A phylogenetic analysis of members of the family Buccinidae was conducted using 18S rRNA gene, 28S rRNA gene and the mi- tochondrial cytochrome oxidase I gene. We studied 18 species of Buccinidae that belong to eight different genera and inhabit the China coastal seas. We analyzed the patterns of divergence between an outgroup and basal ingroup taxa, the monophyly of the genus Neptunea, and the position of one unnamed species within the Buccinidae. A phylogenetic tree (neighbor-joining (NJ) method) was reconstructed based on the sequences of 18S rRNA, 28S rRNA and COI, with Rapana venosa as outgroup. The NJ tree indicated that the 18 species could be divided into five groups. The genus Buccinum was monophyletic, whereas Neptunea was shown to be paraphyletic since it included Siphonalia subdilatata and Neptunea sp., a new species. -

Deep-Water Buccinidae (Gastropoda: Neogastropoda) from Sunken Wood, Vents and Seeps: Molecular Phylogeny and Taxonomy Yu.I

Deep-water Buccinidae (Gastropoda: Neogastropoda) from sunken wood, vents and seeps: molecular phylogeny and taxonomy Yu.I. Kantor, N. Puillandre, K. Fraussen, A.E. Fedosov, P. Bouchet To cite this version: Yu.I. Kantor, N. Puillandre, K. Fraussen, A.E. Fedosov, P. Bouchet. Deep-water Buccinidae (Gas- tropoda: Neogastropoda) from sunken wood, vents and seeps: molecular phylogeny and taxonomy. Journal of the Marine Biological Association of the UK, Cambridge University Press (CUP), 2013, 93 (8), pp.2177-2195. 10.1017/S0025315413000672. hal-02458197 HAL Id: hal-02458197 https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-02458197 Submitted on 28 Jan 2020 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Deep-water Buccinidae (Gastropoda: Neogastropoda) from sunken wood, vents and seeps: Molecular phylogeny and taxonomy KANTOR YU.I.1, PUILLANDRE N.2, FRAUSSEN K.3, FEDOSOV A.E.1, BOUCHET P.2 1 A.N. Severtzov Institute of Ecology and Evolution of Russian Academy of Sciences, Leninski Prosp. 33, Moscow 119071, Russia, 2 Muséum National d’Histoire Naturelle, Departement Systematique et Evolution, UMR 7138, 43, Rue Cuvier, 75231 Paris, France, 3 Leuvensestraat 25, B–3200 Aarschot, Belgium ABSTRACT Buccinidae - like other canivorous and predatory molluscs - are generally considered to be occasional visitors or rare colonizers in deep-sea biogenic habitats.