Burma Tier 1 | Uscirf-Recommended Countries of Particular Concern (Cpc)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Senate TUESDAY, SEPTEMBER 18, 2018

E PL UR UM IB N U U S Congressional Record United States th of America PROCEEDINGS AND DEBATES OF THE 115 CONGRESS, SECOND SESSION Vol. 164 WASHINGTON, TUESDAY, SEPTEMBER 18, 2018 No. 155 House of Representatives The House was not in session today. Its next meeting will be held on Thursday, September 20, 2018, at 9:30 a.m. Senate TUESDAY, SEPTEMBER 18, 2018 The Senate met at 10 a.m. and was U.S. SENATE, until they leaked it to the press on the called to order by the Honorable CINDY PRESIDENT PRO TEMPORE, eve of the scheduled committee vote. Washington, DC, September 18, 2018. HYDE-SMITH, a Senator from the State But as my colleague, the senior Sen- of Mississippi. To the Senate. ator from Texas, said yesterday, the f Under the provisions of rule I, para- graph 3, of the Standing Rules of the blatant malpractice demonstrated by PRAYER Senate, I hereby appoint the Honorable our colleagues across the aisle will not The Chaplain, Dr. Barry C. Black, of- CINDY HYDE-SMITH, a Senator from the stop the Senate from moving forward fered the following prayer: State of Mississippi, to perform the du- in a responsible manner. Let us pray. ties of the Chair. As I said yesterday, I have full con- Eternal God, whose mercy is great ORRIN G. HATCH, unto the Heavens, help us to do what is President pro tempore. fidence in Chairman GRASSLEY to lead right. May we not forget that You are Mrs. HYDE-SMITH thereupon as- the committee through the sensitive the judge of the Earth and that we are sumed the Chair as Acting President and highly irregular situation in which accountable to You. -

The Sentinel Period Ending 27 Oct 2018

The Sentinel Human Rights Action :: Humanitarian Response :: Health :: Education :: Heritage Stewardship :: Sustainable Development __________________________________________________ Period ending 27 October 2018 This weekly digest is intended to aggregate and distill key content from a broad spectrum of practice domains and organization types including key agencies/IGOs, NGOs, governments, academic and research institutions, consortiums and collaborations, foundations, and commercial organizations. We also monitor a spectrum of peer- reviewed journals and general media channels. The Sentinel’s geographic scope is global/regional but selected country-level content is included. We recognize that this spectrum/scope yields an indicative and not an exhaustive product. The Sentinel is a service of the Center for Governance, Evidence, Ethics, Policy & Practice, a program of the GE2P2 Global Foundation, which is solely responsible for its content. Comments and suggestions should be directed to: David R. Curry Editor, The Sentinel President. GE2P2 Global Foundation [email protected] The Sentinel is also available as a pdf document linked from this page: http://ge2p2-center.net/ Support this knowledge-sharing service: Your financial support helps us cover our costs and address a current shortfall in our annual operating budget. Click here to donate and thank you in advance for your contribution. _____________________________________________ Contents [click on link below to move to associated content] :: Week in Review :: Key Agency/IGO/Governments Watch - Selected Updates from 30+ entities :: INGO/Consortia/Joint Initiatives Watch - Media Releases, Major Initiatives, Research :: Foundation/Major Donor Watch -Selected Updates :: Journal Watch - Key articles and abstracts from 100+ peer-reviewed journals :: Week in Review A highly selective capture of strategic developments, research, commentary, analysis and announcements spanning Human Rights Action, Humanitarian Response, Health, Education, Holistic Development, Heritage Stewardship, Sustainable Resilience. -

Administration of Donald J. Trump, 2019 Checklist of White House Press Releases December 31, 2019 January 1 January 3 January 4

Administration of Donald J. Trump, 2019 Checklist of White House Press Releases December 31, 2019 The following list contains releases of the office of the Press Secretary that are neither printed items nor covered by entries in the Digest of Other White House Announcements. January 1 Statement by the Press Secretary on the Federal Government shutdown January 3 Statement by the Press Secretary announcing that the President signed H.R. 1660, H.R. 3460, H.R. 6287, S. 2276, S. 2652, S. 2679, S. 2765, S. 2896, S. 3031, S. 3367, S. 3444, and S. 3777 January 4 Statement by the Press Secretary on scheduled pay increases for administration officials Text of a presentation prepared for Members of Congress by the Department of Homeland Security: A Border Security and Humanitarian Crisis January 7 Statement by the Press Secretary announcing that the President signed S. 2200 and S. 2961 January 8 Statement by the Press Secretary announcing that the President signed H.R. 2200 and S. 3191 Fact sheet: Congress Must Do More To Address the Border Crisis Fact sheet: President Donald J. Trump Calls on Congress To Secure Our Borders and Protect the American People January 9 Statement by the Press Secretary announcing that the President signed S. 1862 and S. 3247 Fact sheet: President Donald J. Trump Is Fighting To Eradicate Human Trafficking January 10 Statement by the Press Secretary announcing that the President signed H.R. 4689, H.R. 5636, H.R. 6602, S. 3456, and S. 3661 Text of an op-ed by Secretary of Homeland Security Kirstjen M. -

ASEAN Responses to Historic and Contemporary Social Challenges” by Lahpai Seng Raw, Founder of Metta Development Foundation, Myanmar

“ASEAN responses to historic and contemporary social challenges” by Lahpai Seng Raw, founder of Metta Development Foundation, Myanmar The keynote speech (and powerpoint presentation) on “ASEAN responses to historic and contemporary social challenges” is scheduled up to 30 minutes. I can understand at a personal level our shared concern about the disappearance of Sombath Somphone, who is also a recipient of the Ramon Magsaysay Award. My husband passed away on a plane crash in Yangon 40 years ago. I gave birth to our son one month after. I felt devastated, as if my world had come to an end, and so when I met Ng Shui Meng for the first time in 2015 in Manila, I thought how terrible it must have been for her, not knowing where her husband was - whether he was dead or alive. On that occasion, I also met Edita Burgos, whose son, Jonas, was abducted in daylight from a shopping mall in 2007. Suddenly, I felt the pain of my widowhood was trivial compared to what Shui Meng, and Edita must be going through - not being able to move on, waiting for information and answers from authorities that are not forthcoming. Most of us, I am sure, can imagine the pain of not knowing where our loved ones are. On the home front, Kachin state in Myanmar, instances of enforced disappearance are not uncommon, either. To cite one well-documented case,1 on 28 October 2011, Sumlut Roi Ja, a 28-year-old Kachin ethnic woman, her husband and father-in- law were arrested together while working in their cornfield in Kachin State by soldiers of Myanmar Government’s Light Infantry Battalion 321. -

DASHED HOPES the Criminalization of Peaceful Expression in Myanmar WATCH

HUMAN RIGHTS DASHED HOPES The Criminalization of Peaceful Expression in Myanmar WATCH Dashed Hopes The Criminalization of Peaceful Expression in Myanmar Copyright © 2019 Human Rights Watch All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America ISBN: 978-1-6231-36970 Cover design by Rafael Jimenez Human Rights Watch defends the rights of people worldwide. We scrupulously investigate abuses, expose the facts widely, and pressure those with power to respect rights and secure justice. Human Rights Watch is an independent, international organization that works as part of a vibrant movement to uphold human dignity and advance the cause of human rights for all. Human Rights Watch is an international organization with staff in more than 40 countries, and offices in Amsterdam, Beirut, Berlin, Brussels, Chicago, Geneva, Goma, Johannesburg, London, Los Angeles, Moscow, Nairobi, New York, Paris, San Francisco, Sydney, Tokyo, Toronto, Tunis, Washington DC, and Zurich. For more information, please visit our website: http://www.hrw.org FEBRUARY 2019 ISBN: 978-1-6231-36970 Dashed Hopes The Criminalization of Peaceful Expression in Myanmar Summary ........................................................................................................................... 1 Methodology ...................................................................................................................... 5 I. Background ..................................................................................................................... 6 II. Section 66(d) -

Congressional Record United States Th of America PROCEEDINGS and DEBATES of the 115 CONGRESS, SECOND SESSION

E PL UR UM IB N U U S Congressional Record United States th of America PROCEEDINGS AND DEBATES OF THE 115 CONGRESS, SECOND SESSION Vol. 164 WASHINGTON, THURSDAY, SEPTEMBER 27, 2018 No. 160 House of Representatives The House met at 10 a.m. and was munity in Wilson, North Carolina, has cellence among the youth in her com- called to order by the Speaker pro tem- lost a giant and a friend. munity. pore (Mr. HARPER). Mr. Speaker, Mrs. Sallie Baldwin Along with many other projects, Mrs. f Howard was born on March 23, 1916, Howard founded the youth enrichment right in the midst of World War I, in program with my good friend, Dr. Jo- DESIGNATION OF SPEAKER PRO Wilson, North Carolina, to Narcissus Anne Woodard, in 1989, focusing the TEMPORE and Marcellus Sims. Even though I did program on lasting scholarship, a com- The SPEAKER pro tempore laid be- not know Mr. Sims, I certainly knew mitment to the cultural heritage of Af- fore the House the following commu- Ms. Narcissus Sims Townsend, who rican Americans, and promoting the nication from the Speaker: lived directly across the street from arts. WASHINGTON, DC, me as a child. Mrs. Howard’s tireless work to enrich September 27, 2018. Though she was raised in the Jim her community inspired Dr. JoAnne I hereby appoint the Honorable GREGG Crow South as the daughter of share- Woodard to create the Sallie B. Howard HARPER to act as Speaker pro tempore on croppers, Mrs. Howard graduated as School for the Arts and Education in this day. -

European Parliament Resolution of 13 September 2018 on Myanmar, Notably the Case of Journalists Wa Lone and Kyaw Soe Oo (2018/2841(RSP))

C 433/124 EN Official Journal of the European Union 23.12.2019 Thursday 13 September 2018 European Parlia- P8_TA(2018)0345 Myanmar, notably the case of journalists Wa Lone and Kyaw Soe Oo European Parliament resolution of 13 September 2018 on Myanmar, notably the case of journalists Wa Lone and Kyaw Soe Oo (2018/2841(RSP)) (2019/C 433/14) The European Parliament, — having regard to its previous resolutions on Myanmar and on the situation of Rohingya people, notably those adopted on 14 June 2018 (1), 14 December 2017 (2), 14 September 2017 (3), 7 July 2016 (4) and 15 December 2016 (5), — having regard to the statement by the spokesperson of the European External Action Service (EEAS) of 3 September 2018 on the sentencing of Wa Lone and Kyaw Soe Oo in Myanmar and that of 9 July 2018 on the prosecution of two Reuters journalists in Myanmar, — having regard to the Council conclusions of 16 October 2017 and of 26 February 2018 on Myanmar, — having regard to Council decisions (CFSP) 2018/655 of 26 April 2018 (6) and (CFSP) 2018/900 of 25 June 2018 (7) imposing fur- ther restrictive measures on Myanmar, strengthening the EU’s arms embargo and targeting the Myanmar army and border guard police officials, — having regard to the report of the Independent International Fact-Finding Mission on Myanmar of the United Nations Human Rights Council of the 24 August 2018, which will be presented at the 39th session of the UN Human Rights Council from 10-28 September 2018, — having regard to the statement of 3 September 2018 by the UN High Commissioner for -

Underneath the Autocrats South East Asia Media Freedom Report 2018

UNDERNEATH THE AUTOCRATS SOUTH EAST ASIA MEDIA FREEDOM REPORT 2018 A REPORT INTO IMPUNITY, JOURNALIST SAFETY AND WORKING CONDITIONS 2 3 IFJ SOUTH EAST ASIA MEDIA FREEDOM REPORT IFJ SOUTH EAST ASIA MEDIA FREEDOM REPORT IFJ-SEAJU SOUTH EAST ASIA MEDIA SPECIAL THANKS TO: EDITOR: Paul Ruffini FREEDOM REPORT Ratna Ariyanti Ye Min Oo December 2018 Jose Belo Chiranuch Premchaiporn DESIGNED BY: LX9 Design Oki Raimundos Mark Davis This document has been produced by the International Jason Sanjeev Inday Espina-Varona Federation of Journalists (IFJ) on behalf of the South East Asia Um Sarin IMAGES: With special thanks Nonoy Espina Journalist Unions (SEAJU) Latt Latt Soe to Agence France-Presse for the Alexandra Hearne Aliansi Jurnalis Independen (AJI) Sumeth Somankae use of images throughout the Cambodia Association for Protection of Journalists (CAPJ) Luke Hunt Eih Eih Tin report. Additional photographs are Myanmar Journalists Association (MJA) Chorrng Longheng Jane Worthington contributed by IFJ affiliates and also National Union of Journalist of the Philippines (NUJP) Farah Marshita Thanida Tansubhapoi accessed under a Creative Commons National Union of Journalists, Peninsular Malaysia (NUJM) Alycia McCarthy Phil Thornton Attribution Non-Commercial Licence National Union of Journalists, Thailand (NUJT) U Kyaw Swar Min Steve Tickner and are acknowledged as such Timor Leste Press Union (TLPU) Myo Myo through this report. 2 3 CONTENTS IFJ SOUTH EAST ASIA MEDIA FREEDOM REPORT 2018 IMPUNITY, JOURNALIST SAFETY AND WORKING CONDITIONS IN SOUTH EAST ASIA -

Annual Report 2019

Annual Report 2019 Join us in defending journalists worldwide @ PressFreedom @ CommitteeToProtectJournalists @ CommitteeToProtectJournalists cpj.org/donate To make a gift to CPJ or to find out about other ways to support our work, please contact us at [email protected] or (212) 465-1004 Cover: Journalists run over a burning barricade during a protest against election results in Madagascar in January. AFP/Mamyrael Committee to Protect Journalists Annual Report 2019 | 1 A photographer takes pictures of Libyan fighters in Tripoli in May. AFP/Mahmud Turkia At least 129 journalists have lost their lives in Syria since its brutal civil war began in 2011. Most were caught in crossfire while covering a war that has inflicted unimaginable devastation and displaced mil- lions. Since CPJ began keeping records, only in Iraq have more journalists perished. Wartime has become deadlier than ever for journalists. So when our Beirut-based representative began receiving pleas for help in the summer of 2018, we knew we had to act. Rebel strongholds were falling to President Bashar al-Assad’s army, and many journalists believed arrest, torture, and death were on the way. They needed to get out of Syria. What unfolded over the next year was an unprecedented effort to win safe passage and refuge for 69 Syrian journalists and their families, an effort we kept quiet until now to protect the journalists and delicate negotiations. The assignment was difficult and emotionally intense for the dedicated CPJ team that carried it out. Few countries were inclined to accept more Syrian refugees. It goes without saying that logistics were tough. -

Page 01 Jan 26.Indd

3rd Best News Website in the Middle East BUSINESS | 21 SPORT | 28 At Davos, Canada Eyeing 3rd spot, and Mexico Qatar out to defy upbeat chill and Korea Friday 26 January 2018 | 9 Jumada 1 | 1439 www.thepeninsula.qa Volume 22 | Number 7418 | 2 Riyals Emir patronises Military College graduation event Emir H H Sheikh Tamim bin Hamad Al Thani reviewed the parade staged by 173 graduates of Ahmed bin Mohammed Military College. QNA DOHA: Emir H H Sheikh Tamim bin Hamad Al Thani patronised the graduation ceremony of the 13th class of officer cadets of Ahmed bin Mohammed Military College, held at the College field yesterday morning. The Qatari national anthem was played upon the Emir’s arrival. The commander of the parade then requested the Emir to review the parade staged by 173 graduates. The graduation ceremony was attended by First Deputy Prime Minister and Minister of Defence of the State of Kuwait, H E Sheikh Nasser Sabah Al Ahmad Al Sabah, a number of Their Excellencies Ministers and ranking officers of the Qatari Armed Forces and the Ministry of Interior, as well as a number of senior officers of military col- Emir H H Sheikh Tamim bin Hamad Al Thani during the graduation ceremony of the 13th class of officer cadets of Ahmed bin Mohammed Military College, yesterday. leges from some brotherly and friendly countries. Delivering a speech on the honour of Emir H H Sheikh Lekhwiya, the Emiri Guard and under the patronage of the Emir, staged a military parade with 14th batch. An order for promo- occasion, Commander of Ahmed Tamim bin Hamad Al Thani of the the State Security Service, in seeks to continue development slow and normal march before tions was read out and the grad- bin Mohammed Military College graduation ceremony. -

Burma's Political Prisoners and U.S. Policy

Burma’s Political Prisoners and U.S. Policy Michael F. Martin Specialist in Asian Affairs Updated May 17, 2019 Congressional Research Service 7-.... www.crs.gov R44804 Burma’s Political Prisoners and U.S. Policy Summary Despite a campaign pledge that they “would not arrest anyone as political prisoners,” Aung San Suu Kyi and the National League for Democracy (NLD) have failed to fulfil this promise since they took control of Burma’s Union Parliament and the government’s executive branch in April 2016. While presidential pardons have been granted for some political prisoners, people continue to be arrested, detained, tried, and imprisoned for alleged violations of Burmese laws. According to the Assistance Association of Political Prisoners (Burma), or AAPP(B), a Thailand-based, nonprofit human rights organization formed in 2000 by former Burmese political prisoners, there were 331 political prisoners in Burma as of the end of April 2019. During its three years in power, the NLD government has provided pardons for Burma’s political prisoners on six occasions. Soon after assuming office in April 2016, former President Htin Kyaw and State Counsellor Aung San Suu Kyi took steps to secure the release of nearly 235 political prisoners. On May 23, 2017, former President Htin Kyaw granted pardons to 259 prisoners, including 89 political prisoners. On April 17, 2018, current President Win Myint pardoned 8,541 prisoners, including 36 political prisoners. In April and May 2019, he pardoned more than 23,000 prisoners, of which the AAPP(B) considered 20 as political prisoners. Aung San Suu Kyi and her government, as well as the Burmese military, however, also have demonstrated a willingness to use Burma’s laws to suppress the opinions of its political opponents and restrict press freedoms. -

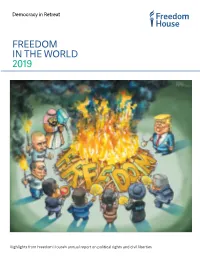

Freedom in the World 2019

Democracy in Retreat FREEDOM IN THE WORLD 2019 Highlights from Freedom House’s annual report on political rights and civil liberties This report was made possible by the generous support of the Achelis & Bodman Foundation, the Jyllands-Posten Foundation, the William and Flora Hewlett Foundation, the William & Sheila Konar Foundation, the Lilly Endowment, and the Fritt Ord Foundation. Freedom House is solely responsible for the report’s content. Freedom in the World 2019 Table of Contents Democracy in Retreat 1 Freedom in the World Methodology 2 Unpacking 13 Years of Decline 4 Regional Trends 9 Freedom in the World 2019 Map 14 Countries in the Spotlight 16 The Struggle Comes Home: Attacks on Democracy in the United States 18 The United States in Decline 23 Recommendations for Democracies 26 Recommendations for the Private Sector 28 The following people were instrumental in the writing of this booklet: Christopher Brandt, Isabel Linzer, Shannon O’Toole, Arch Puddington, Sarah Repucci, Tyler Roylance, Nate Schenkkan, Adrian Shahbaz, Amy Slipowitz, and Caitlin Watson. This booklet is a summary of findings for the 2019 edition of Freedom in the World. The complete analysis, including narrative reports on all countries and territories, can be found on our website at www.freedomhouse.org. ON THE COVER Cover image by KAL. FREEDOM IN THE WORLD 2019 Democracy in Retreat In 2018, Freedom in the World recorded the 13th consecutive year of decline in global freedom. The reversal has spanned a variety of countries in every region, from long-standing democracies like the United States to consolidated authoritarian regimes like China and Russia.