Scott Joplin's Treemonisha”--Gunter Schuller, Arr

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Manatee PIANO MUSIC of the Manatee BERNARD

The Manatee PIANO MUSIC OF The Manatee BERNARD HOFFER TROY1765 PIANO MUSIC OF Seven Preludes for Piano (1975) 15 The Manatee [2:36] 16 Stridin’ Thru The Olde Towne 1 Prelude [2:40] 2 Cello [2:47] During Prohibition In Search Of A Drink [2:42] 3 All Over The Piano [1:21] Randall Hodgkinson, piano 4 Ships Passing [4:12] (2014) BERNARD HOFFER 5 Prelude [1:24] Events & Excursions for Two Pianos 6 Calypso [3:52] 17 Big Bang Theory [3:15] 7 Franz Liszt Plays Ragtime [3:28] 18 Running [3:19] Randall Hodgkinson, piano 19 Wexford Noon [2:29] 20 Reverberations [3:12] Nine New Preludes for Piano (2016) 21 On The I-93 [2:23] Randall Hodgkinson & Leslie Amper, pianos 8 Undulating Phantoms [1:08] BERNARD HOFFER 9 A Walk In The Park [2:39] 10 Speed Chess [2:17] 22 Naked (2010) [5:05] Randall Hodgkinson, piano 11 Valse Sentimental [3:30] 12 Rabbits [1:06] Total Time = 60:03 13 Spirals [1:40] 14 Canon Inverso [1:44] PIANO MUSIC OF TROY1765 WWW.ALBANYRECORDS.COM TROY1765 ALBANY RECORDS U.S. 915 BROADWAY, ALBANY, NY 12207 TEL: 518.436.8814 FAX: 518.436.0643 ALBANY RECORDS U.K. BOX 137, KENDAL, CUMBRIA LA8 0XD TEL: 01539 824008 © 2019 ALBANY RECORDS MADE IN THE USA DDD WARNING: COPYRIGHT SUBSISTS IN ALL RECORDINGS ISSUED UNDER THIS LABEL. The Manatee PIANO MUSIC OF The Manatee BERNARD HOFFER WWW.ALBANYRECORDS.COM TROY1765 ALBANY RECORDS U.S. 915 BROADWAY, ALBANY, NY 12207 TEL: 518.436.8814 FAX: 518.436.0643 ALBANY RECORDS U.K. -

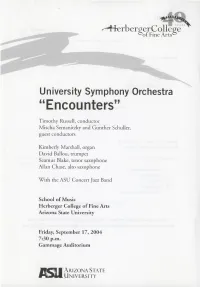

University Symphony Orchestra "Encounters"

FierbergerCollegeYEARS of Fine Arts University Symphony Orchestra "Encounters" Timothy Russell, conductor Mischa Semanitzky and Gunther Schuller, guest conductors Kimberly Marshall, organ David Ballou, trumpet Seamus Blake, tenor saxophone Allan Chase, alto saxophone With the ASU Concert Jazz Band School of Music Herberger College of Fine Arts Arizona State University Friday, September 17, 2004 7:30 p.m. Gammage Auditorium ARIZONA STATE M UNIVERSITY Program Overture to Nabucco Giuseppe Verdi (1813 — 1901) Timothy Russell, conductor Symphony No. 3 (Symphony — Poem) Aram ifyich Khachaturian (1903 — 1978) Allegro moderato, maestoso Allegro Andante sostenuto Maestoso — Tempo I (played without pause) Kimberly Marshall, organ Mischa Semanitzky, conductor Intermission Remarks by Dean J. Robert Wills Remarks by Gunther Schuller Encounters (2003) Gunther Schuller (b.1925) I. Tempo moderato II. Quasi Presto III. Adagio IV. Misterioso (played without pause) Gunther Schuller, conductor *Out of respect for the performers and those audience members around you, please turn all beepers, cell phones and watches to their silent mode. Thank you. Program Notes Symphony No. 3 – Aram Il'yich Khachaturian In November 1953, Aram Khachaturian acted on the encouraging signs of a cultural thaw following the death of Stalin six months earlier and wrote an article for the magazine Sovetskaya Muzika pleading for greater creative freedom. The way forward, he wrote, would have to be without the bureaucratic interference that had marred the creative efforts of previous years. How often in the past, he continues, 'have we listened to "monumental" works...that amounted to nothing but empty prattle by the composer, bolstered up by a contemporary theme announced in descriptive titles.' He was surely thinking of those countless odes to Stalin, Lenin and the Revolution, many of them subdivided into vividly worded sections; and in that respect Khachaturian had been no less guilty than most of his contemporaries. -

Finding Aid for the Sheldon Harris Collection (MUM00682)

University of Mississippi eGrove Archives & Special Collections: Finding Aids Library November 2020 Finding Aid for the Sheldon Harris Collection (MUM00682) Follow this and additional works at: https://egrove.olemiss.edu/finding_aids Recommended Citation Sheldon Harris Collection, Archives and Special Collections, J.D. Williams Library, The University of Mississippi This Finding Aid is brought to you for free and open access by the Library at eGrove. It has been accepted for inclusion in Archives & Special Collections: Finding Aids by an authorized administrator of eGrove. For more information, please contact [email protected]. University of Mississippi Libraries Finding aid for the Sheldon Harris Collection MUM00682 TABLE OF CONTENTS SUMMARY INFORMATION Summary Information Repository University of Mississippi Libraries Biographical Note Creator Scope and Content Note Harris, Sheldon Arrangement Title Administrative Information Sheldon Harris Collection Related Materials Date [inclusive] Controlled Access Headings circa 1834-1998 Collection Inventory Extent Series I. 78s 49.21 Linear feet Series II. Sheet Music General Physical Description note Series III. Photographs 71 boxes (49.21 linear feet) Series IV. Research Files Location: Blues Mixed materials [Boxes] 1-71 Abstract: Collection of recordings, sheet music, photographs and research materials gathered through Sheldon Harris' person collecting and research. Prefered Citation Sheldon Harris Collection, Archives and Special Collections, J.D. Williams Library, The University of Mississippi Return to Table of Contents » BIOGRAPHICAL NOTE Born in Cleveland, Ohio, Sheldon Harris was raised and educated in New York City. His interest in jazz and blues began as a record collector in the 1930s. As an after-hours interest, he attended extended jazz and blues history and appreciation classes during the late 1940s at New York University and the New School for Social Research, New York, under the direction of the late Dr. -

Boston Symphony Orchestra Concert Programs, Summer, 1963-1964

-•-'" 8ft :: -'•• t' - ms>* '-. "*' - h.- ••• ; ''' ' : '..- - *'.-.•..'•••• lS*-sJ BERKSHIRE MUSIC CENTER see ERICH LEINSDORF, Director Contemporary JMusic Presented under the Auspices of the Fromm zMusic Foundation at TANGLEWOOD 1963 SEMINAR in Contemporary Music Seven sessions will be given on successive Friday afternoons (at 3:15) in the Chamber Music Hall. Four of these will precede the four Fromm Fellows' Concerts, and will consist of a re- hearsal and lecture by the Host of the following Monday Fromm Concert. July 12 AARON COPLAND July 19 GUNTHER SCHULLER July 26 I Twentieth Century Piano Music PAUL JACOBS August 2 YANNIS XENAKIS j August 9 Twentieth Century Choral Music ALFRED NASH PATTERSON & LORNA COOKE de VARON August 16 I LUKAS FOSS August 23 Round Table Discussion of Contemporary Music Yannis Xenakis, Gunther Schuller and lukas foss Composers 9 Forums There will be four Composers' Forums in the Chamber Music Hall: Wednesday, July 24 at 4:00 ] Thursday, August 1 at 8:00 Wednesday, August 7 at 4:00 Thursday, August 15 at 8:00 FROMM FELLOWS' CONCERTS Theatre-Concert Hall Four Monday Evenings at 8:00 'Programs JULY 15 AUGUST 5 AARON COPLAND, Host YANNIS XENAKIS, Host Varese Octandre (1924) Boulez ...Improvisations sur Mallarme, Copland Sextet (1937) No. 2 Chavez Soli (1933) Philippot ...Variations Schoenberg String Quartet No. 2, Op. 10 Mdcbe .. ..Canzone II (1908) Brown, E ...Pentathis Stravinsky Ragtime for Eleven Instruments Marie, E... Polygraphie-Polyphonique (1918) J. Ballif,C ...Double Trio, 35, Nos. 2 and 3 Milhaud... L'Enlevement d'Europe — Op. Xenakis Achorripsis Opera minute (1927) JULY 22 AUGUST 19 GUNTHER SCHULLER, Host LUKAS FOSS, Host Ives Chromatimelodtune Paz .Dedalus, 1950 Schoenberg Herzgewacb.se Goehr... -

Scott Joplin International Ragtime Festival

Scott Joplin International Ragtime Festival By Julianna Sonnik The History Behind the Ragtime Festival Scott Joplin - pianist, composer, came to Sedalia, studied at George R. Smith College, known as the King of Ragtime -Music with a syncopated beat, dance, satirical, political, & comical lyrics Maple Leaf Club - controversial, shut down by the city in 1899 Maple Leaf Rag (1899) - 76,000 copies sold in the first 6 months of being published -Memorial concerts after his death in 1959, 1960 by Bob Darch Success from the Screen -Ragtime featured in the 1973 movie “The Sting” -Made Joplin’s “The Entertainer” and other music popular -First Scott Joplin International Ragtime Festival in 1974, 1975, then took a break until 1983 -1983 Scott Joplin U.S. postage stamp -TV show possibilities -Sedalia realized they were culturally important, had way to entice their town to companies The Festival Today -38 festivals since 1974 -Up to 3,000 visitors & performers a year, from all over the world -2019: 31 states, 4 countries (Brazil, U.K., Japan, Sweden, & more) -Free & paid concerts, symposiums, Ragtime Footsteps Tour, ragtime cakewalk dance, donor party, vintage costume contest, after-hours jam sessions -Highly trained solo pianists, bands, orchestras, choirs, & more Scott Joplin International Ragtime Festival -Downtown, Liberty Center, State Fairgrounds, Hotel Bothwell ballroom, & several other venues -Scott Joplin International Ragtime Foundation, Ragtime store, website -2020 Theme: Women of Ragtime, May 27-30 -Accessible to people with disabilities -Goals include educating locals about their town’s culture, history, growing the festival, bringing in younger visitors Impact on Sedalia & America -2019 Local Impact: $110,335 -Budget: $101,000 (grants, ticket sales, donations) -Target Market: 50+ (56% 50-64 years) -Advertising: billboards, ads, newsletter, social media -Educational Programs: Ragtime Kids, artist-in-residence program, school visits -Ragtime’s trademark syncopated beat influenced modern America’s music- hip-hop, reggae, & more. -

MUNI 20101013 Piano 02 – Scott Joplin, King of Ragtime – Piano Rolls

MUNI 20101013 Piano 02 – Scott Joplin, King of Ragtime – piano rolls An der schönen, blauen Donau – Walzer, op. 314 (Johann Strauss, Jr., 1825-1899) Wiener Philharmoniker, Carlos Kleiber. Musikverein Wien, 1. 1. 1989 1 intro A 1:38 2 A 32 D 0:40 3 B 16 A 0:15 4 B 16 0:15 5 C 16 D 0:15 6 C 16 0:15 7 D 16 Bb 0:17 8 C 16 D 0:15 9 E 16 G 0:15 10 E 16 0:15 11 F 16 0:14 12 F 16 0:13 13 modul. 4 ►F 0:05 14 G 16 0:20 15 G 16 0:18 16 H 16 0:14 17 H 16 0:15 18 10+1 ►A 0:10 19 I 16 0:17 20 I 16 0:16 21 J 16 0:13 22 J 16 0:13 23 16+2 ►D 0:16 24 C 16 0:15 25 16 ►F 0:15 26 G 14 0:17 27 11 ►D 0:10 28 A 0:39 29 A1 16 0:16 30 A2 0:12 31 stretta 0:10 The Entertainer (Scott Joplin) (copyright John Stark & Son, Sedalia, 29. 12. 1902) piano roll Classics of Ragtime 0108 32 intro 4 C 0:06 33 A 16 0:23 34 A 16 0:23 35 B 16 0:23 36 B 16 0:23 37 A 16 0:23 38 C 16 F 0:22 39 C 16 0:22 40 modul. 4 ►C 0:05 41 D 16 0:22 42 D 16 0:23 43 The Crush Collision March (Scott Joplin, 1867/68-1917) 4:09 (J. -

The Miseducation of Hip-Hop Dance: Authenticity, and the Commodification of Cultural Identities

The Miseducation of Hip-Hop dance: Authenticity, and the commodification of cultural identities. E. Moncell Durden., Assistant Professor of Practice University of Southern California Glorya Kaufman School of Dance Introduction Hip-hop dance has become one of the most popular forms of dance expression in the world. The explosion of hip-hop movement and culture in the 1980s provided unprecedented opportunities to inner-city youth to gain a different access to the “American” dream; some companies saw the value in using this new art form to market their products for commercial and consumer growth. This explosion also aided in an early downfall of hip-hop’s first dance form, breaking. The form would rise again a decade later with a vengeance, bringing older breakers out of retirement and pushing new generations to develop the technical acuity to extraordinary levels of artistic corporeal genius. We will begin with hip-hop’s arduous beginnings. Born and raised on the sidewalks and playgrounds of New York’s asphalt jungle, this youthful energy that became known as hip-hop emerged from aspects of cultural expressions that survived political abandonment, economic struggles, environmental turmoil and gang activity. These living conditions can be attributed to high unemployment, exceptionally organized drug distribution, corrupt police departments, a failed fire department response system, and Robert Moses’ building of the Cross-Bronx Expressway, which caused middle and upper-class residents to migrate North. The South Bronx lost 600,000 jobs and displaced more than 5,000 families. Between 1973 and 1977, and more than 30,000 fires were set in the South Bronx, which gave rise to the phrase “The Bronx is Burning.” This marginalized the black and Latino communities and left the youth feeling unrepresented, and hip-hop gave restless inner-city kids a voice. -

Central Opera Service Bulletin

CENTRAL OPERA SERVICE BULLETIN WINTER, 1972 Sponsored by the Metropolitan Opera National Council Central Opera Service • Lincoln Center Plaza • Metropolitan Opera • New York, N.Y. 10023 • 799-3467 Sponsored by the Metropolitan Opera National Council Central Opera Service • Lincoln Canter Plaza • Metropolitan Opera • New York, NX 10023 • 799.3467 CENTRAL OPERA SERVICE COMMITTEE ROBERT L. B. TOBIN, National Chairman GEORGE HOWERTON, National Co-Chairman National Council Directors MRS. AUGUST BELMONT MRS. FRANK W. BOWMAN MRS. TIMOTHY FISKE E. H. CORRIGAN, JR. CARROLL G. HARPER MRS. NORRIS DARRELL ELIHU M. HYNDMAN Professional Committee JULIUS RUDEL, Chairman New York City Opera KURT HERBERT ADLER MRS. LOUDON MEI.LEN San Francisco Opera Opera Soc. of Wash., D.C. VICTOR ALESSANDRO ELEMER NAGY San Antonio Symphony Ham College of Music ROBERT G. ANDERSON MME. ROSE PALMAI-TENSER Tulsa Opera Mobile Opera Guild WILFRED C. BAIN RUSSELL D. PATTERSON Indiana University Kansas City Lyric Theater ROBERT BAUSTIAN MRS. JOHN DEWITT PELTZ Santa Fe Opera Metropolitan Opera MORITZ BOMHARD JAN POPPER Kentucky Opera University of California, L.A. STANLEY CHAPPLE GLYNN ROSS University of Washington Seattle Opera EUGENE CONLEY GEORGE SCHICK No. Texas State Univ. Manhattan School of Music WALTER DUCLOUX MARK SCHUBART University of Texas Lincoln Center PETER PAUL FUCHS MRS. L. S. STEMMONS Louisiana State University Dallas Civic Opera ROBERT GAY LEONARD TREASH Northwestern University Eastman School of Music BORIS GOLDOVSKY LUCAS UNDERWOOD Goldovsky Opera Theatre University of the Pacific WALTER HERBERT GIDEON WALDKOh Houston & San Diego Opera Juilliard School of Music RICHARD KARP MRS. J. P. WALLACE Pittsburgh Opera Shreveport Civic Opera GLADYS MATHEW LUDWIG ZIRNER Community Opera University of Illinois See COS INSIDE INFORMATION on page seventeen for new officers and members of the Professional Committee. -

Scott Joplin: Maple Leaf

Maple Leaf Rag Scott Joplin Born: ? 1867 Died: April 1, 1917 Unlike many Afro-American children in the 1880s who did not get an education, According to the United States Scott attended Lincoln High School census taken in July of 1870, in Sedalia, Missouri, and later went to Scott Joplin was probably born George R. Smith College for several years. in late 1867 or early 1868. No Throughout his life, Joplin believed one is really sure where he was in the importance of education and born either. It was probably in instructed young musicians whenever northeast Texas. he could. Joplin was a self-taught Although he composed several marches, musician whose father was a some waltzes and an opera called laborer and former slave; his Treemonisha, Scott Joplin is best known mother cleaned houses. The for his “rags.” Ragtime is a style of second of six children, Scott music that has a syncopated melody in was always surrounded with which the accents are on the off beats, music. His father played the on top of a steady, march-like violin while his mother sang accompaniment. It originated in the or strummed the banjo. Scott Afro-American community and became often joined in on the violin, a dance craze that was enjoyed by the piano or by singing himself. dancers of all races. Joplin loved this He first taught himself how to music, and produced over 40 piano play the piano by practicing in “rags” during his lifetime. Ragtime the homes where his mother music helped kick off the American jazz worked; then he took lessons age, growing into Dixieland jazz, the from a professional teacher who blues, swing, bebop and eventually rock also taught him how music was ‘n roll. -

View PDF Online

MARLBORO MUSIC 60th AnniversAry reflections on MA rlboro Music 85316_Watkins.indd 1 6/24/11 12:45 PM 60th ANNIVERSARY 2011 MARLBORO MUSIC Richard Goode & Mitsuko Uchida, Artistic Directors 85316_Watkins.indd 2 6/23/11 10:24 AM 60th AnniversA ry 2011 MARLBORO MUSIC richard Goode & Mitsuko uchida, Artistic Directors 85316_Watkins.indd 3 6/23/11 9:48 AM On a VermOnt HilltOp, a Dream is BOrn Audience outside Dining Hall, 1950s. It was his dream to create a summer musical community where artists—the established and the aspiring— could come together, away from the pressures of their normal professional lives, to exchange ideas, explore iolinist Adolf Busch, who had a thriving music together, and share meals and life experiences as career in Europe as a soloist and chamber music a large musical family. Busch died the following year, Vartist, was one of the few non-Jewish musicians but Serkin, who served as Artistic Director and guiding who spoke out against Hitler. He had left his native spirit until his death in 1991, realized that dream and Germany for Switzerland in 1927, and later, with the created the standards, structure, and environment that outbreak of World War II, moved to the United States. remain his legacy. He eventually settled in Vermont where, together with his son-in-law Rudolf Serkin, his brother Herman Marlboro continues to thrive under the leadership Busch, and the great French flutist Marcel Moyse— of Mitsuko Uchida and Richard Goode, Co-Artistic and Moyse’s son Louis, and daughter-in-law Blanche— Directors for the last 12 years, remaining true to Busch founded the Marlboro Music School & Festival its core ideals while incorporating their fresh ideas in 1951. -

Production Database Updated As of 25Nov2020

American Composers Orchestra Works Performed Workshopped from 1977-2020 firstname middlename lastname Date eventype venue work title suffix premiere commission year written Michael Abene 4/25/04 Concert LGCH Improv ACO 2004 Muhal Richard Abrams 1/6/00 Concert JOESP Piano Improv Earshot-JCOI 19 Muhal Richard Abrams 1/6/00 Concert JOESP Duet for Violin & Piano Earshot-JCOI 19 Muhal Richard Abrams 1/6/00 Concert JOESP Duet for Double Bass & Piano Earshot-JCOI 19 Muhal Richard Abrams 1/9/00 Concert CH Tomorrow's Song, as Yesterday Sings Today World 2000 Ricardo Lorenz Abreu 12/4/94 Concert CH Concierto para orquesta U.S. 1900 John Adams 4/25/83 Concert TULLY Shaker Loops World 1978 John Adams 1/11/87 Concert CH Chairman Dances, The New York ACO-Goelet 1985 John Adams 1/28/90 Concert CH Short Ride in a Fast Machine Albany Symphony 1986 John Adams 12/5/93 Concert CH El Dorado New York Fromm 1991 John Adams 5/17/94 Concert CH Tromba Lontana strings; 3 perc; hp; 2hn; 2tbn; saxophone1900 quartet John Adams 10/8/03 Concert CH Christian Zeal and Activity ACO 1973 John Adams 4/27/07 Concert CH The Wound-Dresser 1988 John Adams 4/27/07 Concert CH My Father Knew Charles Ives ACO 2003 John Adams 4/27/07 Concert CH Violin Concerto 1993 John Luther Adams 10/15/10 Concert ZANKL The Light Within World 2010 Victor Adan 10/16/11 Concert MILLR Tractus World 0 Judah Adashi 10/23/15 Concert ZANKL Sestina World 2015 Julia Adolphe 6/3/14 Reading FISHE Dark Sand, Sifting Light 2014 Kati Agocs 2/20/09 Concert ZANKL Pearls World 2008 Kati Agocs 2/22/09 Concert IHOUS -

Record Series 1121-113, W. W. Law Sheet Music and Songbook

Record Series 1121-113, W. W. Law Sheet Music and Songbook Collection by Title Title Added Description Contributor(s) Date(s) Item # Box Publisher Additional Notes A Heritage of Spirituals Go Tell it on the Mountain for chorus of mixed John W. Work 1952 voices, three part 1121-113-001_0110 1121-113-001 Galaxy Music Corporation A Heritage of Spirituals Go Tell it on the Mountain for chorus of women's John W. Work 1949 voices, three part 1121-113-001_0109 1121-113-001 Galaxy Music Corporation A Heritage of Spirituals I Want Jesus to Walk with Me Edward Boatner 1949 1121-113-001_0028 1121-113-001 Galaxy Music Corporation A Heritage of Spirituals Lord, I'm out Here on Your Word for John W. Work 1952 unaccompanied mixed chorus 1121-113-001_0111 1121-113-001 Galaxy Music Corporation A Lincoln Letter Ulysses Kay 1958 1121-113-001_0185 1121-113-001 C. F. Peters Corporation A New Song, Three Psalms for Chorus Like as a Father Ulysses Kay 1961 1121-113-001_0188 1121-113-001 C. F. Peters Corporation A New Song, Three Psalms for Chorus O Praise the Lord Ulysses Kay 1961 1121-113-001_0187 1121-113-001 C. F. Peters Corporation A New Song, Three Psalms for Chorus Sing Unto the Lord Ulysses Kay 1961 1121-113-001_0186 1121-113-001 C. F. Peters Corporation Friday, November 13, 2020 Page 1 of 31 Title Added Description Contributor(s) Date(s) Item # Box Publisher Additional Notes A Wreath for Waits II. Lully, Lully Ulysses Kay 1956 1121-113-001_0189 1121-113-001 Associated Music Publishers Aeolian Choral Series King Jesus is A-Listening, negro folk song William L.