Macaca Fascicularis) in West Sumatra, Indonesia

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Herman Miller Materialuebersicht Sayl

Unity/Nexus Camira Composition: Polyester 100% Application: Width 170cm +/- 2% Usable Weight: 300g/m² +/- 5% (530g/linear metre +/- 5%) price Band 2 Standards: BS 2543: 1995/2004 Flammability: BS 476 part 7 class 1, Light Fastness: 5 (ISO 105-B02: 1999) Fastness to Rubbing: Wet: 4 Dry: 4 (ISO 105 – X12:2002) Colour Matching: Batch to batch variations in shade may occur within commercial tolerances. Maintenance: Vacuum regularly. Wipe clean with a damp cloth. 293 Unity/Nexus Pewter UNY01 Olive UNY09 Berry UNY04 Pacific UNY03 ID01 ID09 ID04 ID03 Sky UNY06 Storm UNY07 Chalk UNY12 Graphite UNY11 ID06 ID07 ID12 ID11 Petrol UNY10 Limestone UNY02 ID10 ID02 Kiwi UNY05 Denim UNY08 Russian UNY16 Oceanic UNY15 Black UNY13 ID05 ID08 ID16 ID15 ID13 295 Phoenix Camira Composition: polyester 100% Application: Width: 140cm +/- 2% Usable Weight: 285g/m² +/- 5% (400g/linear metre +/- 5%) Price Band 0 Standards: Abrasion Resistance: 100,000 Martindale cycles Flammability: BS EN 1021-1:2006, BS EN 1021-2:2006, BS EN 7176 :2007 Light Fastness: 6 (ISO 105-B02: 1999) Fastness to Rubbing: Wet: 4 Dry: 4 (ISO 105 – X12:2002) Colour Matching: Batch to batch variations in shade may occur within commercial tolerances. Maintenance: Vacuum regularly. Wipe clean with a damp cloth. 211 Phoenix Havana YP009 Sombrero YP046 Rainforest YP114 Windjammer YP047 7o009 7O046 7O114 7O047 Paseo YP019 Blizzard YP081 Campeche YP112 Arawak YP016 7O019 7O081 7O112 7O016 Nougat YP111 Sandstorm YP107 Costa YP026 7O111 7O107 7O026 Montserrat YP011 Taboo YP045 Apple YP108 Ocean YP100 7O011 -

For Index to These, See Pages Xiv, Xv.)

INDEX THis Index contains no reference to the Introductory Tables, nor to the Additions and Corrections. (For index to these, see pages xiv, xv.) AAC ADI AAcHEN (Prussia), 926, 957; tech- Aburi (Gold Coast), 258 nical schools, 928 ABYSSINIA, 213, 630 sqq Aalborg (Denmark), 784 - boundary, 213, 263, 630, 905, Aalen (Wiirttemberg), 965 1029 Aarau (Switzerland), 1311 - commerce, 634, 905 Aargau (Switzerland), 1308, 1310 - King Regent, 631, 632, 633 Aarhus (Denmark), 784 - leased territory, 263, 632 Abaco Island (Bahamas), 332 - railways, 634, 905 Abaiaug !Rland (Pacific), 421 - religion, 632, 815 Abancay (Peru), 1175 - roads, 634, 905 Abdul Aziz ibn Saud, Sultan of N ejd, -trade routes, 634, 905 645, 646, 647; Wahhabi war Abyssinian race, 632 under, 645, 646, 647, 1323 Acajutla (Salvador), port, 1252 Abdul Hamid Halim Shah, Sultan, Acarnania (Greece), 968 (Kedah), 182 Acchele Guzai (Eritrea), 1028 Abdullah, Sultan (Pahang), 177 Accra (Gold Coast), 256 Abdullah Ibn Hussein, Amir of - wireless station, 258 Trans-J orrlan, 191 Accrington, 14 Abemama Is. (Pacific), 421 Acha!a (Greece), 968 Abercorn (N. Rhodesia), 221 Achirnota Univ. Col!. (Gold Coast), Aberdeen, burgh, 17 256 - county, 17 Acklin's Island (Bahamas), 332 -university, 22, 23 Aconcagua (Chile), prov., 718 Aberdeen (South Dakota), 586 Acre (Palestine), 186, 188; port, Aberdeen (Washington, U.S.A), 601 190 Aberystwyth College, 22 Acre Territory (Brazil), 698 ; rubber, Abeshr (Wadai), 898 702 Abba (Yemen), 648, 649 Adalia (Turkey), vilayet, 1324 Abidjan (French West Africa), 910 Adana (Turkey), vilayet, 1324; min Abkhasian, Soviet Rep. (Georgia), ing, 1328; town, 1324, 1329 1247 Addis Ababa (Abyssinia), 631, 632, Abo (Finland), 834; university, 834 634, 905 Abo-Bjorneborg (Finland), 833 Adeiso (Gold Coast), 258 Aboisso (French West Africa), 910 Adelaide (S. -

Dutch Atlantic Connections, 1680–1800 Linking Empires, Bridging Borders

Dutch Atlantic Connections, 1680–1800 Linking Empires, Bridging Borders Gert Oostindie and Jessica V. Roitman d Dutch Atlantic Connections, 1680–1800 <UN> Atlantic World europe, africa and the americas, 1500–1830 Edited by Benjamin Schmidt (University of Washington) Wim Klooster (Clark University) VOLUME 29 The titles published in this series are listed at brill.com/aw <UN> Dutch Atlantic Connections, 1680–1800 Linking Empires, Bridging Borders Edited by Gert Oostindie Jessica V. Roitman LEIDEN | BOSTON <UN> The digital edition of this title is published in Open Access. This is an open access title distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial 3.0 Unported (CC-BY-NC 3.0) License, which permits any non-commercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited. Cover Illustration: Artist unknown, Het fregat Vertrouwen voor anker op de rede van Paramaribo, 1800, Collection Het Scheepvaartmuseum, The National Maritime Museum, Amsterdam. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Dutch Atlantic connections, 1680-1800 : linking empires, bridging borders / edited by Gert Oostindie, Jessica V. Roitman. pages cm. -- (Atlantic world : Europe, Africa and the Americas, ISSN 1570-0542, volume 29) Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-90-04-27132-6 (hardback : alkaline paper) -- ISBN 978-90-04-27131-9 (e-book) 1. Netherlands-- Commerce--America--History--17th century. 2. Netherlands--Commerce--America--History--18th century. 3. America--Commerce--Netherlands--History--17th century. 4. America--Commerce-- Netherlands--History--18th century. 5. Netherlands--Foreign economic relations--Spain. 6. Spain-- Foreign economic relations--Netherlands. 7. Netherlands--Foreign economic relations--France. -

U.S. and Affiliates, Bermuda and Bahamas

U.S. and Affiliates, Bermuda and Bahamas 65539 District 1 F BARRINGTON ### 65540 District 1 G FRANKLIN ### 65542 District 1 J BURR RIDGE-HINSDALE-OAK BROOK WESTMONT ### 65549 District 2 E2 DENTON HI NOON SHERMAN NOON ### 65553 District 2 A1 LLANO ### 65559 District 2 S4 EL CAMPO HALLETTSVILLE ### 65569 District 4 C4 MILLBRAE ### 65570 District 4 C5 ROSEVILLE SUNRISE ### 65571 District 4 C6 GILROY ### 65573 District 4 A2 FOWLER ### 65575 District 4 L1 NORTHRIDGE ### Monday, November 05, 2018 Page 1 of 26 Premier Club Centennial Awards U.S. and Affiliates, Bermuda and Bahamas 65576 District 4 L2 LONG BEACH BELMONT SHORE WHITTIER SPECIAL OLYMPICS SOLA ### 65577 District 4 L3 LOS ANGELES BRILLIANT LOS ANGELES SEOUL ### 65579 District 4 L5 COACHELLA VALLEY ### 65582 District 5M 1 KELLOGG ### 65583 District 5M 2 LESTER PRAIRIE NORTHFIELD CANNON VALLEY ### 65586 District 5M 5 EXCELSIOR ### 65592 District 5M 11 FOSSTON-LENGBY GOODRIDGE ### 65596 District 5 NW STANLEY WASHBURN ### 65603 District 5 SW MC LAUGHLIN ### 65604 District 6 NE LYONS ### 65607 District 6 W BASALT ### 65615 District 8 N BATON ROUGE METROPOLITAN ### 65628 District 11 A2 CENTER LINE ### Monday, November 05, 2018 Page 2 of 26 Premier Club Centennial Awards U.S. and Affiliates, Bermuda and Bahamas 65629 District 11 B1 VANDERCOOK LAKE ### 65634 District 11 D2 PEARL BEACH ### 65637 District 12 L BARTLETT ### 65640 District 12 N TELLICO VILLAGE ### 65641 District 12 S RED BOILING SPRINGS ### 65652 District 14 A BUCKS CO ASSN - BLIND & VISUALLY ### IMPAIRED 65654 District 14 C HANOVER ### 65658 District 14 G WYALUSING ### 65664 District 14 N FORD CITY ### 65667 District 14 T PORT ROYAL ### 65697 District 19 I FORKS ### 65700 District 20 E2 RUSHVILLE ### Monday, November 05, 2018 Page 3 of 26 Premier Club Centennial Awards U.S. -

Distribution and Collecting Method of Fingerling Eeel (Anguilla Sp.) in Bengkulu Province

International Seminar on Promoting Local Resources for Food and Health, 12-13 October, 2015, Bengkulu, Indonesia Distribution and Collecting Method of Fingerling Eeel (Anguilla Sp.) in Bengkulu Province Dede Hartono, Deddy Bakhtiar, Zamdial Ta’alidin Department of Marine Science Bengkulu University Corresponding author email: [email protected] ABSTRACT Indonesia is an archipelago that is rich in resources eels (Anguilla Sp.). There are at least six types of eel, Anguilla mormorata, Anguilla celebensis, Anguilla ancentralis, Anguilla borneensis, and Anguilla bicolor, Anguilla pacifica. The types of eels are spread in areas bordering the deep sea. Nevertheless eels are not yet widely used economically. Whereas the eels in both, the size of the seed and the size for consumption are abundant. Bengkulu Province is located at latitude 2 16 '- 3 31' and 101 1 '- 103 41' E, which is located on the western edge of the island of Sumatera. Western parts of Bengkulu province directly dealing with the Indian Ocean with a coastline of about 525 km long. In the very long coastline it flows 134 rivers and creeks. Bengkulu province occupies most of the western slopes of the Bukit Barisan Mountains. In such areas generally have rivers shorter. In accordance with the topography is hilly and steep, generally torrential streams and rafting. The condition is an ideal habitat for eels. This study aims to determine the distribution and collecting method of fingerling eels in Bengkulu water body, especially rivers, as well as knowing the environmental conditions eel habitat. The method used in the study is the survey method, by direct observation in the field. -

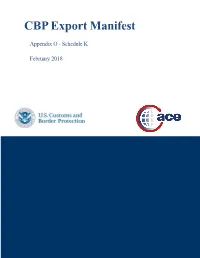

ACE Export Manifest

CBP Export Manifest Appendix O - Schedule K February 2018 CBP Export Manifest Schedule K Appendix O This appendix provides a complete listing of foreign port codes in Alphabetical order by country. Foreign Port Codes Code Ports by Country Albania 48100 All Other Albania Ports 48109 Durazzo 48109 Durres 48100 San Giovanni di Medua 48100 Shengjin 48100 Skele e Vlores 48100 Vallona 48100 Vlore 48100 Volore Algeria 72101 Alger 72101 Algiers 72100 All Other Algeria Ports 72123 Annaba 72105 Arzew 72105 Arziw 72107 Bejaia 72123 Beni Saf 72105 Bethioua 72123 Bona 72123 Bone 72100 Cherchell 72100 Collo 72100 Dellys 72100 Djidjelli 72101 El Djazair 72142 Ghazaouet 72142 Ghazawet 72100 Jijel 72100 Mers El Kebir 72100 Mestghanem 72100 Mostaganem 72142 Nemours 72179 Oran Schedule K Appendix O F-1 CBP Export Manifest 72189 Skikda 72100 Tenes 72179 Wahran American Samoa 95101 Pago Pago Harbor Angola 76299 All Other Angola Ports 76299 Ambriz 76299 Benguela 76231 Cabinda 76299 Cuio 76274 Lobito 76288 Lombo 76288 Lombo Terminal 76278 Luanda 76282 Malongo Oil Terminal 76279 Namibe 76299 Novo Redondo 76283 Palanca Terminal 76288 Port Lombo 76299 Porto Alexandre 76299 Porto Amboim 76281 Soyo Oil Terminal 76281 Soyo-Quinfuquena term. 76284 Takula 76284 Takula Terminal 76299 Tombua Anguilla 24821 Anguilla 24823 Sombrero Island Antigua 24831 Parham Harbour, Antigua 24831 St. John's, Antigua Argentina 35700 Acevedo 35700 All Other Argentina Ports 35710 Bagual 35701 Bahia Blanca 35705 Buenos Aires 35703 Caleta Cordova 35703 Caleta Olivares 35703 Caleta Olivia 35711 Campana 35702 Comodoro Rivadavia 35700 Concepcion del Uruguay 35700 Diamante 35700 Ibicuy Schedule K Appendix O F-2 CBP Export Manifest 35737 La Plata 35740 Madryn 35739 Mar del Plata 35741 Necochea 35779 Pto. -

Recovery Cooperation for Padang Earthquake Damage by Seismic Isolation Buildings Design

RECOVERY COOPERATION FOR PADANG EARTHQUAKE DAMAGE BY SEISMIC ISOLATION BUILDINGS DESIGN EWBJ (Engineers without Boarder, Japan) Takayuki Teramoto Toshio Okoshi Tokyo University of Science Tokyo Polytechnic University Tokyo/ Japan Tokyo/ Japan Abstract At September 2009, the earthquake of M7.6 occurred around Padang city of Sumatra, Indonesia. Non- profit-organization EWBJ (Engineers without Border, Japan) have cooperated to research the seismic damage and have proposed for the recovery and strengthening of damaged governmental buildings by the financial support of Japan Platform. After these, local government of South-Sumatra decided to construct new governmental buildings by the seismic isolation technique and requested to cooperate for EWBJ. EWBJ has cooperated for two seismic isolation building projects with Andalas university engineers of Padang. And two governmental buildings are now under construction. 1 Time-history of the Cooperation (1) Sep. 2009 Padang earthquake occurred. (2) Oct. 2009 1st cooperation of earthquake damage research Earthquake damage s were researched by the association team of EWBJ (Engineers without Boarder, Japan), JSCE (Japan Society of Civil Engineers), JSAEE (Japan Association for Earthquake Engineering). (3) Dec. 2009 2nd cooperation of earthquake damage recovery EWBJ members of architectural team (Teramoto & Okoshi) and civil team visited Padang for the cooperation of earthquake damage recovery. Finally two symposiums were held at Padang and Jakarta (4) Apr. 2010 3rd cooperation for earthquake damage recovery EWBJ architectural team held a symposium at Padang about the design techniques of seismic isolation buildings. At the end of this visit, EWBJ was requested the design cooperation of five seismic isolation buildings by local government. EWBJ agreed to this and the seismic isolation design cooperation project was started from this time. -

Geographic Coordinate Systems, Datums, Spheroids, Prime Meridians, and Angular Units of Measure

Geographic coordinate systems, datums, spheroids, prime meridians, and angular units of measure Current as of ArcGIS version 9.3 Angular Units of Measure ArcSDE macro ArcObjects macro code name radians / unit PE_U_RADIAN esriSRUnit_Radian 9101 Radian 1.0 PE_U_DEGREE esriSRUnit_Degree 9102 Degree p/180 PE_U_MINUTE esriSRUnit_Minute 9103 Arc–minute (p/180)/60 PE_U_SECOND esriSRUnit_Second 9104 Arc–second (p/180)/3600 PE_U_GRAD esriSRUnit_Grad 9105 Grad p/200 PE_U_GON esriSRUnit_Gon 9106 Gon p/200 PE_U_MICRORADIAN esriSRUnit_Microradian 9109 Microradian 1.0E-6 PE_U_MINUTE_CENTESIMAL esriSRUnit_Minute_Centesimal 9112 Centesimal minute p/20000 PE_U_SECOND_CENTESIMAL esriSRUnit_Second_Centesimal 9113 Centesimal second p/2000000 PE_U_MIL_6400 esriSRUnit_Mil_6400 9114 Mil p/3200 Spheroids Macro Code Name a (m) 1/f esriSRSpheroid_Airy1830 7001 Airy 1830 6377563.396 299.3249646 esriSRSpheroid_ATS1977 7041 ATS 1977 6378135.0 298.257 esriSRSpheroid_Australian 7003 Australian National 6378160 298.25 esriSRSpheroid_AuthalicSphere 7035 Authalic sphere (WGS84) 6371000 0 esriSRSpheroid_AusthalicSphereArcInfo 107008 Authalic sph (ARC/INFO) 6370997 0 esriSRSpheroid_AusthalicSphere_Intl1924 7057 Authalic sph (Int'l 1924) 6371228 0 esriSRSpheroid_Bessel1841 7004 Bessel 1841 6377397.155 299.1528128 esriSRSpheroid_BesselNamibia 7006 Bessel Namibia 6377483.865 299.1528128 esriSRSpheroid_Clarke1858 7007 Clarke 1858 6378293.639 294.2606764 esriSRSpheroid_Clarke1866 7008 Clarke 1866 6378206.4 294.9786982 esriSRSpheroid_Clarke1866Michigan 7009 Clarke 1866 Michigan -

Experts Meeting on Sources of Tsunamis in the Lesser Antilles

Intergovernmental Oceanographic Commission Workshop Report No. 291 Experts Meeting on Sources of Tsunamis in the Lesser Antilles Fort-de-France, Martinique (France) 18–20 March 2019 UNESCO Intergovernmental Oceanographic Commission Workshop Report No. 291 Experts Meeting on Sources of Tsunamis in the Lesser Antilles Fort-de-France, Martinique (France) 18–20 March 2019 UNESCO 2020 IOC Workshop Reports, 291 Paris, September 2020 English only The authors are responsible for the choice and the presentation of the facts contained in this publication and for the opinions expressed therein, which are not necessarily those of UNESCO and do not commit the Organization. Every care has been taken to ensure the accuracy of information in this publication. However, neither UNESCO, nor the authors will be liable for any loss or damaged suffered as a result of reliance on this information, or through directly or indirectly applying it. The designations employed and the presentation of the material in this publication do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the Secretariats of UNESCO and IOC concerning the legal status of any country or territory, or its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of the frontiers of any country or territory. For bibliographic purposes this document should be cited as follows: IOC-UNESCO. 2020. Experts Meeting on Sources of Tsunamis in the Lesser Antilles. Fort-de- France, Martinique (France), 18–20 March 2019. Paris, UNESCO. (Workshop Reports, 291). Published in 2020 by the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization 7, place de Fontenoy, 75352 Paris 07 SP (IOC/2020/WR/291) IOC Workshop Reports, 291 page (i) TABLE OF CONTENTS page Executive Summary ............................................................................................................ -

Dinamika Pengaruh Berbagai Macam Dan Taraf Bahan Tambahan Mudah Didapat Pada Kualitas Fisik Silase Rumput Padang Golf

Prosiding Seminar Teknologi dan Agribisnis Peternakan VIII–Webinar: “Peluang dan Tantangan Pengembangan Peternakan Terkini untuk Mewujudkan Kedaulatan Pangan” Fakultas Peternakan Universitas Jenderal Soedirman, 24-25 Mei 2021, ISBN: 978-602-52203-3-3 DINAMIKA PENGARUH BERBAGAI MACAM DAN TARAF BAHAN TAMBAHAN MUDAH DIDAPAT PADA KUALITAS FISIK SILASE RUMPUT PADANG GOLF Eko Hendarto*, Bahrun, Nur Hidayat dan Harwanto Fakultas Peternakan, Universitas Jenderal Soedriman *Korespondensi e-mail: [email protected] Abstrak. Penelitian tentang silase telah dilakukan untuk mendapatkan informasi potensi kontinyuitas penyediaan hijauan pakan terutama pada usaha ternak ruminansia. Salah satu sumber hijauan yang dapat dimanfaatkan dan produksinya berlimpah adalah rumput padang golf Wijayakusuma Purwokerto. Rumput Bermuda (Cynodon dactylon) dominan tumbuh pada padang golf Wijayakusuma Purwokerto. Penelitian bertujuan untuk mendapatkan informasi potensi pemanfaatan rumput padang golf sebagai silase penyedia pakan ruminansia diamati dari karakter fisiknya. Digunakan bahan tambahan dedak, cacahan ketela pohon dan cacahan ketela rambat. Dosis yang digunakan 5, 10 dan 15 persen dari bobot hijauan, sehingga terdapat 9 perlakuan. Ulangan 3 kali. Rancangan yang digunakan Rancangan Acak Lengkap (RAL). Parameter yang diamati meliputi tekstur, warna, keberadaan jamur dan pH. Data yang diperoleh dianalisis berdasarkan Rancangan Acak Lengkap. Hasil penelitian memperlihatkan bahwa dinamika silase rumput padang golf memiliki karakteristik kondisi yang baik pada parameter yang diteliti di semua perlakuan dan siap mendukung penyediaan hijauan pakan. Berdasarkan hal tersebut semua bahan tambahan dapat digunakan untuk bahan pembuatan silase rumput padang golf guna pemenuhan kebutuhan hijauan bagi ternak ruminansia. Kata Kunci: silase, bahan tambahan, rumput Bermuda, padang golf Abstract. A research of silage was conducted to obtain information of potent of forage availability especially for ruminant farming. -

The Design of Hotel Performance Management System in Padang

Proceedings of the International MultiConference of Engineers and Computer Scientists 2015 Vol II, IMECS 2015, March 18 - 20, 2015, Hong Kong The Design of Hotel Performance Management System in Padang Difana Meilani, Ilham Anugrah and various chips Sanjai, are the tourist attractions of Abstract— As a tourist place, Indonesia is supported by its Padang. So it can be concluded that tourism sector is the beautiful natural scenaries and unique cultures. Actually most focus of development and the biggest income of Padang. of Indonesia incomes came from tourism sectors. Padang as the Realizing tourism as an economic power of Padang, administrative center of West Sumatra is one of tourism places revamping and improving the assessment of development of in Indonesia. Unfortunately, all the facilities and touris actractions here need improvement, for example the hotels. various objects are needed. One of the objects is the hotels. Hotels in Padang need attention on the performance Hotels are included as a primary means of supporting management system. One of the them is Premier Basko Hotel. tourism activities. From interviewing IHRA executive This hotel depends on profit targets and classification of IHRA director of West Sumatra, Elvis Syarif, he said that, the (Indonesian Hotel & Restaurant Association). For the hospitality industries like hotels need a guidance for internal increasement of this hotel, SWOT (Strength, Weakness, performance improvement. Opportunity, Threats) analysis and balanced scorecard method were applied. It began with the strategic information gathering Premier Basko Hotel is one of the 52 unit hotels in based on interviewing the company, then continue processing it Padang [3]. This Hotel is located at Jalan Prof. -

Diageo 2017 Annual Report

154 DIAGEO ANNUAL REPORT 2017 Financial statements of the company: Notes to the company financial statements of Diageo plc 69 Building 3, Maxwell Office Park, Magwa Crescent West, Waterfall City, Midrand, 2090, 121 Plot 3-17 Port Bell Road Luzira Kampala P.O. Box 7130 Kampala, Uganda South Africa 122 UB Tower #24, Vittal Mallya Road, UB City, Bangalore-560001, India 70 Rue du Grand-Pré 2 b CH-1007 Lausanne, Switzerland 123 Labatt House, Suite 299, 207 Queen's Quay West, Toronto ON, M5J 1A7, Canada 71 Estrada Nacional numero 1, Micanhine, Marracuene, Mozambique 124 Guinness Brewery, Plot 1 Block L, Industrial Area, Kaasi, P. O. Box 1536, Kumasi, Ghana 72 Gavlegatan Street 22/C Stockholm 11330, Sweden 125 Plot No 1 Malt Road, Portbell Luzira P.O. Box 3221 Kampala, Uganda 73 Plaza 2000, 16th Floor, 50th Street, P.O. Box 0816-01098, Panama City, Panama 126 2711 Centerville Road, Suite 400, Wilmington, Delaware 19808, USA, United States 74 Ukraine, 02152, Kyiv, 1v Pavla Tychyny avenue, office V704, Ukraine 127 Edificio Vallarino, Penthouse Calle 52 y Elvira Mendez P. O. Box 0816-06805, Panama 75 Av. Luis A. de Herrera, 1.248, WTC- Torre II - office 1074, Montevideo, Uruguay 128 Sea Meadow House, Blackburne Highway, P.O. Box 116, Road Town, Tortola, British 76 State of Delaware, 3411 Silverside Road, Rodney Building #104, Wilmington, DE Virgin Islands 19810, New Castle County, United States 129 UB House, Plot No-36, Street no-4, Srinagar Colony, Hyderabad-500073, India 77 1131 King Street, Christiansted, St. Croix, U.S. Virgin Islands 00820-4971, United States 130 OMC Chambers, Wickhams Cay 1, Road Town, Tortola, British Virgin Islands 78 Ave.