North Peace Goat Inventory 2014

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

South Peace Fringe Area Official Community Plan Bylaw No

Peace River Regional District South Peace Fringe Area Official Community Plan Bylaw No. 2048, 2012 ____________________________________________________________ Effective Date – April 16, 2021 Consolidated for convenience only This is a consolidation of the bylaws listed below. The amending bylaws have been combined with the original bylaw for convenience only. This consolidation is not a legal document. Certified copies of the original bylaws should be consulted for all interpretations and applications of the bylaw on this subject. Original Bylaw Date of Adoption Bylaw No. 2048, 2012 July 25, 2013 Amending bylaws: Text Amendments: Map Amendments: Bylaw No. 2106, 2014 Bylaw No. 2184, 2014 Bylaw No. 2228, 2015 Bylaw No. 2250, 2016 Bylaw No. 2289, 2017 PEACE RIVER REGIONAL DISTRICT South Peace Fringe Area Official Community Plan Bylaw No. 2048, 2012 TABLE OF CONTENTS SECTION 1 – INTRODUCTION AND BACKGROUND ..............................................................6 1.1 What is the Official Community Plan? ........................................................................6 1.2 Planning Area ............................................................................................................6 1.3 The Planning Process ...............................................................................................8 SECTION 2 - REGIONAL HISTORY AND OVERVIEW ..............................................................9 2.1 History ......................................................................................................................9 -

1.1 Rocky Mountain Elk (Cervus Elaphus Nelsoni)

1.1 Rocky Mountain Elk (Cervus elaphus nelsoni) SPECIES NAME: Rocky mountain elk SCIENTIFIC NAME: Cervus elaphus nelsoni SPECIES CODES: M-CEEL STATUS: Not at risk (MELP, 1997; COSEWIC, 1998) DISTRIBUTION Provincial Range Rocky Mountain elk primarily occur in the Kootenays, the lower Peace River area and the Muskwa-Prophet River drainages on the eastern slope of the Rocky Mountains. Although Rocky Mountain elk were historically abundant and widely distributed in the Cariboo-Chilcotin and Thompson-Nicola areas, elk declined for unknown reasons and today only small, widely scattered herds remain in these areas. Provincial Benchmark Ecoprovince: Northern Boreal Mountains Ecoregion: Northern Mountains and Plateaus and Northern Canadian Rocky Mountains Ecosection: Muskwa Foothils (MUF) Biogeoclimatic zone: SWBmk Broad Ecosystem Units: SM - Subalpine Meadow Project Study Area Ecoprovince: Northern Boreal Mountains Ecoregion: Northern Mountains and Plateaus and Northern Canadian Rocky Mountains Ecosection: Cassiar Ranges (CAR), Western Muskwa Ranges (WMR), Eastern Muskwa Ranges (EMR) and Missinchninka Ranges (MIR) Biogeoclimatic zone: BWBSdk1, SWBmk1, ESSFmv4, SWBmks1, ESSFmvp4 and AT Elevational range: Valley bottom to alpine The Akie and Pesika River drainages contain small populations of elk (Wood, 1994; Hatler, 1990; Wood, pers. comm.). The summer population is larger due to seasonal migrations from the Muskwa/Prophet river drainages and other adjacent areas (Wood, pers. comm.). Hatler (1990) and Wildlife Branch (1990b) found 22 and 19 elk respectively wintering in the upper Akie River drainage. A small population of elk reside along the Ingenika River. In 1996, 50 elk were transplanted into this area to supplement the original population of 20 to 30. The population is currently estimated at 40 to 50 individuals (Wood, pers. -

Muskwa-Kechika Expedition and Camps 2021

Muskwa-Kechika Expedition and Camps 2021 General Information The Muskwa-Kechika Management Area (M-KMA) encompasses a vast wilderness in BC’s northern Rocky Mountains. Teeming with wildlife, it is a vestige of the continental wilderness that once existed. MK Adventures has been leading expeditions into the remotest regions of the MK as part of an effort to protect this magnificent area for decades. You have an opportunity to become one of five participants on each expedition, where you will experience the ride of your life - a rewarding and full-on challenge for both the mind and body. MK Adventures 2021 Expedition Lineup - a year of changes In 2021 we will set off from from the Alaska Highway on June 15 and return on Sept 4. Detailed info is below. Wayne is turning 65 this fall, and while he feels as strong as ever, there comes a time when one has to dial back some of the more rigorous tasks. As a result he will be stepping back from the two week Expeditions, but will ride the Gatho Exploration Expedition, June 28 -July 12, and our Mayfield Experiences, July 26 - August 13. Alex and Michelle have been key members of the operation for a decade now, and in addition to leading the Muskwa-Kechika Adventures PO Box 27, Rolla BC, V0C 2G0 (250) 261-1513 email [email protected], Hit www.go2mk.ca Page 1 Expeditions in 2021 are planning to take over the reins from MK Adventures permanently. We will see what the future holds! Another change we have made for 2021 is to lower the number of guest riders from six or seven per trip down to five. -

Northern Rocky Mountains Park Kłôwāh’ Chô ‐ Big Grass Management Plan

Northern Rocky Mountains Park Kłôwāh’ chô ‐ Big Grass Management Plan Draft Nov 2011 Cover Photo: Tuchodi River – BC Parks Image Bank Kłôwāh’ chô ‐ Big Grass Kaska First Nations name sake Management Plan Northern Rocky Mountains Park Management Plan Approved by: ______________________________ __________________ First Nation Date ______________________________ __________________ Brian Bawtinheimer Date Director, Parks Planning and Management Branch BC Parks ______________________________ __________________ Larry Boudreau Date Regional Manager, Northern Region BC Parks Northern Rocky Mountains Management Plan Acknowledgements The Ministry of Environment (MoE) – BC Parks acknowledges and thanks the following participants for their dedication and hard work in the development of this Management Plan. BC Parks recognizes that most people donated a great deal of their personal time in order to help us in preparing and writing the document. Their sacrifice is acknowledged and greatly appreciated. These people are passionate regarding this area now known as the Northern Rocky Mountains Park. Public Advisory Group: A genuine thank you is extended to the members of the Northern Rocky Mountains Public Advisory Group for their dedication, support, sharing of knowledge and concern for this wonderful Park. Each member of the Public Advisory Group below had an alternate and represented a sector. Interest Representative Alternate Aviation‐ Commercial Larry Moody Rob Morrison Aviation‐ Recreation Dwayne Palmer John Todd Boating‐ Commercial Cam Allen Guy -

Glaciers of the Canadian Rockies

Glaciers of North America— GLACIERS OF CANADA GLACIERS OF THE CANADIAN ROCKIES By C. SIMON L. OMMANNEY SATELLITE IMAGE ATLAS OF GLACIERS OF THE WORLD Edited by RICHARD S. WILLIAMS, Jr., and JANE G. FERRIGNO U.S. GEOLOGICAL SURVEY PROFESSIONAL PAPER 1386–J–1 The Rocky Mountains of Canada include four distinct ranges from the U.S. border to northern British Columbia: Border, Continental, Hart, and Muskwa Ranges. They cover about 170,000 km2, are about 150 km wide, and have an estimated glacierized area of 38,613 km2. Mount Robson, at 3,954 m, is the highest peak. Glaciers range in size from ice fields, with major outlet glaciers, to glacierets. Small mountain-type glaciers in cirques, niches, and ice aprons are scattered throughout the ranges. Ice-cored moraines and rock glaciers are also common CONTENTS Page Abstract ---------------------------------------------------------------------------- J199 Introduction----------------------------------------------------------------------- 199 FIGURE 1. Mountain ranges of the southern Rocky Mountains------------ 201 2. Mountain ranges of the northern Rocky Mountains ------------ 202 3. Oblique aerial photograph of Mount Assiniboine, Banff National Park, Rocky Mountains----------------------------- 203 4. Sketch map showing glaciers of the Canadian Rocky Mountains -------------------------------------------- 204 5. Photograph of the Victoria Glacier, Rocky Mountains, Alberta, in August 1973 -------------------------------------- 209 TABLE 1. Named glaciers of the Rocky Mountains cited in the chapter -

A National Ecological Framework for Canada

A NATIONAL ECOLOGICAL FRAMEWORK FOR CANADA Written and compiled by: Ecological Stratification Working Group Centre for Land and Biological State of the Environment Directorate Resources Research Environment Conservation Service Research Branch Environment Canada Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada ---- Copies of this report and maps available from: Canadian Soil Information System (CanSIS) Centre for Land and Biological Resources Research Research Branch, Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada Ottawa, ON KIA OC6 State of the Environment Directorate Environmental Conservation Service Environment Canada Hull, PQ KIA OH3 Printed and digital copies of the six regional ecodistrict and ecoregion maps at scale of 1:2 million (Atlantic Provinces #CASOlO; Quebec #CASOll; Ontario #CAS012; Manitoba, Saskatchewan, and Alberta #CAS013; British Columbia and Yukon Territory #CASOI4; and the Northwest Territories #CASOI5); and associated databases are available from Canadian Soil Information System (CanSIS), address as above. co Minister of Supply and Services Canada 1996 Cat. No. A42-65/1996E ISBN 0-662-24107-X Egalement disponible en fran91is sous Ie titre Cadrc ecologiqllc national po"r Ie Canada Bibliographic Citation: Ecological Stratification Working Group. 1995. A National Ecological Framework for Canada. Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada, Research Branch, Centre for Land and Biological Resources Research and Environment Canada, State of the Environment Directorate, Ecozone Analysis Branch, Ottawa/Hull. Report and national map at 1:7500 000 scale. TABLE OF CONTENTS Preface iv Acknowledgemenl<; v 1. Ecolo~cal Re~onalization in Canada 1 2. Methodology. .. .. 2 Map COlnpilation . .. 2 Levels of Generalization. .. 2 Ecozones 2 Ecoregions . 4 Ecodistricts 4 Data Integration. .. 6 3. The Ecological Framework 8 4. Applications of the Framework 8 Reporting Applications. -

The Letters F and T Refer to Figures Or Tables Respectively

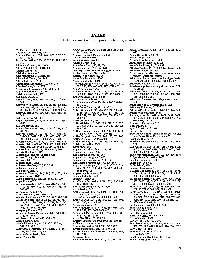

INDEX The letters f and t refer to figures or tables respectively "A" Marker, 312f, 313f Amherstberg Formation, 664f, 728f, 733,736f, Ashville Formation, 368f, 397, 400f, 412, 416, Abitibi River, 680,683, 706 741f, 765, 796 685 Acadian Orogeny, 686, 725, 727, 727f, 728, Amica-Bear Rock Formation, 544 Asiak Thrust Belt, 60, 82f 767, 771, 807 Amisk lowlands, 604 Askin Group, 259f Active Formation, 128f, 132f, 133, 139, 140f, ammolite see aragonite Assiniboia valley system, 393 145 Amsden Group, 244 Assiniboine Member, 412, 418 Adam Creek, Ont., 693,705f Amundsen Basin, 60, 69, 70f Assiniboine River, 44, 609, 637 Adam Till, 690f, 691, 6911,693 Amundsen Gulf, 476, 477, 478 Athabasca, Alta., 17,18,20f, 387,442,551,552 Adanac Mines, 339 ancestral North America miogeocline, 259f Athabasca Basin, 70f, 494 Adel Mountains, 415 Ancient Innuitian Margin, 51 Athabasca mobile zone see Athabasca Adel Mountains Volcanics, 455 Ancient Wall Complex, 184 polymetamorphic terrane Adirondack Dome, 714, 765 Anderdon Formation, 736f Athabasca oil sands see also oil and gas fields, Adirondack Inlier, 711 Anderdon Member, 664f 19, 21, 22, 386, 392, 507, 553, 606, 607 Adirondack Mountains, 719, 729,743 Anderson Basin, 50f, 52f, 359f, 360, 374, 381, Athabasca Plain, 617f Aftonian Interglacial, 773 382, 398, 399, 400, 401, 417, 477f, 478 Athabasca polymetamorphic terrane, 70f, Aguathuna Formation, 735f, 738f, 743 Anderson Member, 765 71-72,73 Aida Formation, 84,104, 614 Anderson Plain, 38, 106, 116, 122, 146, 325, Athabasca River, 15, 20f, 35, 43, 273f, 287f, Aklak -

CUPP Newsletter Fall 2011

CUPP 2011 NEWSLETTER CUPP in Third Decade Oxford Courtyard CUPP Work Crew Martin Nunn, Dmytro Kaniewski, Roman Tashlitsky, Yaroslav Kovalchuk Yaroslava Barbieri, Vira Makovii, Olesia Stasiv, Vasyl Lenko McGregor Matthews Room, New College James Sherr with CUPP Alumni Punting on the Oxford CANADA-UKRAINE PARLIAMENTARY PROGRAM ваний поляками, а тоді – мо- магазинні прилавки, алюмінієві лодецький і чорновусий Лех підстаканники та іржавий руко- Валенса виступив проти – мирно мийник постановочної, начебто і переконливо. Протягом певно- тюремної, камери у місцевому го часу судноверф Гданська – Музеї «Солідарності». І зазирає у свого роду держава з населен- наші обличчя, намагаючись від- ням-робітниками чисельністю найти чи то захоплення, чи по- близько 300 тисяч осіб – зуміла див… А наша українська група об’єднатися і сказати: “Ні, ми не мовчки розглядає її довгі сереж- задоволені». ки з неприродньо світлим бурш- Ця подія серпня 1980-го року, тиновим камінням – усе-таки тут коли було підписано перший до- він вважається одним із найкра- говір із комуністичним режимом, щих у світі. стала початком. Але не початком Захоплення немає. Та й по- кінця, а справжнім – із бажаним диву теж. Швидше – роздрату- продовженням. вання. Що за цінність така, та ще Гданськ – портове, наче ма- й музейна? Нам ці «експонати» – Olena Shapoval льоване, місто Балтійського ще звична справа. Напевно, ра- Taras Shevchenko National Uni- узбережжя. У 68-му тут вийшли дянське життя у нас залишило versity of Kyiv студенти, у 70-му – робітники, у значно більше слідів, які, як ви- Vadym Hetman National Economic 80-му – «солідарність» на судно- явилося, не стерти політичними University of Kyiv верфі, а у 89-му тут мовчки кри- заявами та обіцянками… [email protected] чав Папа Іоанн Павло ІІ… Поляки пам’ятають усе це; не А згодом збагнулося: саме Музей одного покоління пам’ятають порожніх прилавків і такі музеї і є прекрасними, над- старих телефонних будок – у них звичайно важливими й потрібни- У цій країні слово «солідар- це вже музейні експонати, – але ми для нас. -

Rangifer Tarandus Caribou) in BRITISH COLUMBIA

THE EARLY HISTORY OF WOODLAND CARIBOU (Rangifer tarandus caribou) IN BRITISH COLUMBIA by David J. Spalding Wildlife Bulletin No. B-100 March 2000 THE EARLY HISTORY OF WOODLAND CARIBOU (Rangifer tarandus caribou) IN BRITISH COLUMBIA by David J. Spalding Ministry of Environment, Lands and Parks Wildlife Branch Victoria BC Wildlife Bulletin No. B-100 March 2000 “Wildlife Bulletins frequently contain preliminary data, so conclusions based on these may be sub- ject to change. Bulletins receive some review and may be cited in publications. Copies may be obtained, depending upon supply, from the Ministry of Environment, Lands and Parks, Wildlife Branch, P.O. Box 9374 Stn Prov Gov, Victoria, BC V8W 9M4.” © Province of British Columbia 2000 Canadian Cataloguing in Publication Data Spalding, D. J. The early history of woodland caribou (Rangifer tarandus caribou) in British Columbia (Wildlife bulletin ; no. B-100) Includes bibliographical references : p. 60 ISBN 0-7726-4167-6 1. Woodland caribou - British Columbia. 2. Woodland caribou - Habitat - British Columbia. I. British Columbia. Wildlife Branch. II. Title. III. Series: Wildlife bulletin (British Columbia. Wildlife Branch) ; no. B-100 QL737.U55S62 2000 333.95’9658’09711 C00-960085-X Citation: Spalding, D.J. 2000. The Early History of Woodland Caribou (Rangifer tarandus caribou) in British Columbia. B.C. Minist. Environ., Lands and Parks, Wildl. Branch, Victoria, BC. Wildl. Bull. No. 100. 61pp. ii DISCLAIMER The views expressed herein are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily represent those of the B.C. Ministry of Environment, Lands and Parks. In cases where a Wildlife Bulletin is also a species’ status report, it may contain a recommended status for the species by the author. -

Tuchodi Prescribed Burns Presentation

Tuchodi Prescribed Burns for Wildlife Habitat Supplemental Information 2020 A.D. Woods October 2020 Prepared for the Ministry of Forests, Lands, Natural Resource Operations and Rural Development, Northeast Region EXECUTIVE SUMMARY Northeastern British Columbia (BC) has a long history of the use of prescribed fire for wildlife habitat improvement and enhancement, which has primarily been conducted by the Province of BC and, historically, First Nations. The Tuchodi River valley, located in the Northern Rocky Mountains Provincial Park, is renowned for the diversity and abundance of wildlife within it, which has been shaped and maintained through the implementation of prescribed burns for the past 50 years. Persistence of these wildlife values is important for traditional use by First Nations, biodiversity, and recreational opportunities. The purpose of the multi-year Tuchodi prescribed burn program is to restore early seral ecosystems to support healthy wildlife populations dependent upon these habitats. Early and mid-seral habitats, including natural grasslands and grassland-shrub complexes, will be treated with prescribed fire to increase the quantity and quality of forage, increase the traverse-ability of sites by removing blow down, and decrease vertical structure to meet the seasonal foraging requirements of each species. Effectiveness of the prescribed burns will be assessed by measuring and comparing vegetative response and changes in wildlife use before and after the prescribed fire treatment. Funding for this project was provided by the Habitat Conservation Trust Foundation and the North Peace Rod & Gun Club. Suggested Citation: Woods, A.D. 2020. Tuchodi prescribed burns for wildlife habitat: supplemental information 2020. Ridgeline Wildlife Enhancement Report #007, Ridgeline Wildlife Enhancement, Fort St. -

KECHIKA MANAGEMENT AREA (MKMA) Volume 1: Final Report

CONSERVATION AREA DESIGN for the MUSKWA - KECHIKA MANAGEMENT AREA (MKMA) Volume 1: Final Report Kim Heinemeyer, Rick Tingey, Kristine Ciruna, Tom Lind, Jacob Pollock, Bart Butterfield, Julian Griggs, Pierre Iachetti, Collin Bode, Tom Olenicki, Eric Parkinson, Chuck Rumsey and Dennis Sizemore July 31, 2004 Nature Conservancy of Canada Round River Conservation Studies Dovetail Consulting Inc. CONSERVATION AREA DESIGN for the MUSKWA - KECHIKA MANAGEMENT AREA (MKMA) Volume 1: Final Report Kim Heinemeyer, Rick Tingey, Kristine Ciruna, Tom Lind, Jacob Pollock, Bart Butterfield, Julian Griggs, Pierre Iachetti, Collin Bode, Tom Olenicki, Eric Parkinson, Chuck Rumsey and Dennis Sizemore July 31, 2004 Nature Conservancy of Canada Round River Conservation Studies Dovetail Consulting Inc. CONSERVATION AREA DESIGN for the MUSKWA - KECHIKA MANAGEMENT AREA (MKMA) Authors and their affiliations: Dr. Kimberly Heinemeyer, Research Director, Round River Conservation Studies Rick Tingey, GIS Specialist, Round River Conservation Studies Jacob Pollock, Research Associate, Round River Conservation Studies Dennis Sizemore, Executive Director, Round River Conservation Studies Tom Lind, GIS Analyst, Round River Conservation Studies Dr. Kristine Ciruna, Conservation Programs Coordinator, Nature Conservancy of Canada, BC Region Pierre Iachetti, Conservation Planning Coordinator, Nature Conservancy of Canada, BC Region Bart Butterfield, Independent Consultant Julian Griggs, Principal, Dovetail Consultants Tom Olenicki, GIS Analyst, Craighead Environmental Research Institute Collin Bode, Independent Consultant Dr. Eric Parkinson, Ecosystem Science Specialist, BC Ministry of Water, Air, and Land Protection Chuck Rumsey, Executive Director, Round River Canada Citation: Heinemeyer, K., R. Tingey, , K. Ciruna, T. Lind, J. Pollock, B. Butterfield, J. Griggs, P. Iachetti, C. Bode, T. Olenicki, E. Parkinson, C. Rumsey and D. Sizemore. 2004. Conservation Area Design for the Muskwa-Kechika Management Area. -

Redfern-Keily Park Management Plan

Redfern-Keily Park Management Plan Draft Nov 2011 Management Plan Redfern-Keily Park Management Plan Approved by: ______________________________ __________________ First Nation Date ______________________________ __________________ Brian Bawtinheimer Date Director, Parks Planning and Management Branch BC Parks ______________________________ __________________ Larry Boudreau Date Regional Manager, Northern Region BC Parks Redfern‐Keily Park Management Plan Acknowledgements This plan was produced by BC Parks staff of the Northern Region ‐ Peace Section of the Ministry of Environment (MOE). A majority of the draft plan was written by Marilynn Hagedorn, Planning Assistant. General direction was provided by Don Roberts, MOE Project Manager. Jeff Burrows, MOE Senior Fish Biologist, Bryan Webster, MOE Senior Wildlife Biologist, and Rob Honeyman, North Peace Area Supervisor, provided valuable technical assistance. Mapping and GIS analysis was provided by Jason Kubian, MOE Data Technician. Thank you to the individuals who completed and returned the Community Involvement Workbooks. Your insights, comments and suggestions were greatly appreciated and helped us to achieve a better understanding of the management issues in Redfern‐Keily Park. We would especially like to express our appreciation to the Muskwa‐Kechika Advisory Board Trust Fund for providing support through all the phases of plan development. Thank you. Redfern‐Keily Park Management Plan i Vision Statement This vision statement describes the future state and management regime that is desired for Redfern‐Keily Park over the next 25 to 50 years. It provides long term direction for park managers, while aiding them in making decisions regarding current issues. It is based on prevailing environmental and socio‐economic attitudes concerning protected areas, and is also based, in part, on the conservation and recreation contributions of Redfern‐Keily Park to the provincial Protected Areas Strategy.